Planes de atención a niños y adolescentes con asma en España, un análisis por comunidades autónomas

Natalia Rivas Abraldesa, Águeda García Merinob

aPediatra. CS Mungia. Vizcaya. España.

bPediatra. CS Vallobín-Las Campas. Oviedo. Asturias. España.

Correspondencia: N Rivas . Correo electrónico: natalia_take@hotmail.com

Cómo citar este artículo: Rivas Abraldes N, García Merino A. Planes de atención a niños y adolescentes con asma en España, un análisis por comunidades autónomas. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2022;24:e11-e25.

Publicado en Internet: 12-04-2022 - Número de visitas: 14894

Resumen

Introducción y objetivo: describir cómo realizan los pediatras de Atención Primaria (PAP) el manejo de los niños y adolescentes con asma en España.

Material y métodos: estudio transversal, observacional y descriptivo para conocer los planes/guías de atención al asma en edad pediátrica por comunidades autónomas (CC. AA.), y ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla, la inclusión de esta actividad en sus carteras de servicios (CS) y cómo se registra en la historia clínica informatizada del paciente, mediante encuesta telemática a las asociaciones autonómicas de PAP, y telefónica para Ceuta y Melilla. En los planes encontrados, se evaluó la presencia de criterios diagnósticos, tratamiento y seguimiento del asma, recursos disponibles e indicadores de calidad asistencial, de acuerdo con un protocolo definido y adaptado a las recomendaciones de las guías de práctica clínica, y el grado de variabilidad de los mismos.

Resultados: el 50% de las CC. AA. españolas tienen planes para el manejo de niños y adolescentes con asma, en diez se incluye esta actividad en su CS y 11 disponen de módulo de registro informático específico. De los nueve documentos encontrados, tres son planes y seis guías. Los primeros obtienen mayor puntuación global al aplicar el protocolo. De los parámetros estudiados, solo tener documento escrito y clasificar la gravedad del asma al diagnóstico figuran en todos los planes.

Conclusiones: en España hay una gran variabilidad en la atención al asma en Pediatría y no todas las CC. AA. tienen implementados planes de trabajo, ni registro informatizado de esta actividad. Para garantizar la equidad en el manejo de estos pacientes convendría que todas las regiones implantasen un plan integral de atención actualizado.

Palabras clave

● Asma ● Atención Primaria de Salud ● Guías de práctica clínica ● Pediatría ● Programas Nacionales de Salud ● Recursos en saludINTRODUCCIÓN

El asma es posiblemente la enfermedad crónica más frecuente en la infancia y adolescencia en muchas partes del mundo, incluida España, donde afecta a uno de cada diez niños, con amplias variaciones geográficas1,2. Supone, además, un problema de salud pública de gran magnitud porque disminuye la calidad de vida de los niños y sus familiares y produce elevados costes sociosanitarios1-3.

En términos económicos, se calcula que es responsable del 1-2% del gasto sanitario. La mayor parte de los costes son directos (60%) siendo el más elevado el gasto de la asistencia en Atención Primaria (AP). El mayor porcentaje de los gastos indirectos (40%) corresponde al cuidado del menor en el domicilio1-3.

Desde hace más de 20 años se han ido editando y actualizando guías clínicas de consenso para el manejo del asma, tanto nacionales como internacionales, para adultos y, más recientemente, para niños. Estas guías pretenden ser un material uniforme, referenciado y basado en la mejor evidencia científica para establecer recomendaciones diagnósticas y terapéuticas, y garantizar una asistencia homogénea de calidad1.

Sin embargo, en el manejo del asma es preciso también una adecuada planificación y organización mediante programas que incluyan la adaptación y coordinación de los recursos materiales y humanos necesarios para seguir las recomendaciones de las guías4-6. La evaluación de planes europeos nacionales y regionales de atención a niños y adultos con asma ha puesto de manifiesto que el empleo de programas integrales que coordinen a todos los profesionales implicados favorece el control del asma a corto y largo plazo disminuye gastos directos e indirectos relacionados con la enfermedad y mejora la calidad de vida de pacientes y familias4,7.

En España, la atención sanitaria de los niños es universal y fácilmente accesible, los pediatras de Atención Primaria (PAP) son su principal puerta de entrada al Sistema Nacional de Salud (SNS), correspondiéndoles, en primer lugar, el manejo de gran parte de las patologías crónicas de la infancia incluida el asma. Sin embargo, las transferencias sanitarias a las comunidades autónomas (CC. AA.) han conllevado enfoques distintos en las prioridades de las prestaciones ofertadas. Si bien la atención al asma en la infancia y adolescencia queda incluida dentro de la cartera de servicios (CS) común para AP del SNS, en el apartado Servicios de Atención a la Infancia y Adolescencia, el desarrollo de este servicio ha sido muy diferente en cada una de ellas, tanto en lo referente al desarrollo de planes de manejo de la enfermedad, como en la inclusión en su CS3,8,9 y en el registro de esta actividad en la historia clínica informatizada del paciente.

El objetivo de este trabajo es conocer cómo se realiza la atención a los niños y adolescentes con asma en España por parte de los PAP en las diferentes CC. AA., Ceuta y Melilla, en relación con el empleo de planes/guías para su manejo, su inclusión en la CS de su comunidad autónoma (CA) y el registro informático de los datos relacionados con el control y seguimiento de esta patología. Así mismo, en aquellas en las que la atención se lleve a cabo según un plan/guía propio, realizar un análisis de este con el fin de evaluar los criterios utilizados para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad, los recursos materiales y humanos disponibles, su distribución y organización durante el seguimiento de los niños y adolescentes con asma, los indicadores de calidad asistencial empleados para su evaluación y las actualizaciones realizadas.

MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS

Diseño: la investigación se llevó a cabo mediante un estudio descriptivo trasversal para conocer y evaluar los contenidos de los planes de atención al niño/a y adolescente con asma en España por CC. AA., así como para Ceuta y Melilla, la inclusión de estos en sus respectivas CS y como se realiza el registro de los datos de esta actividad en la historia clínica informatizada.

Procedimiento: para la recogida de los planes en las diferentes CC. AA., Ceuta y Melilla se emplearon los métodos que se describen a continuación.

Revisión de publicaciones:

- Literatura científica, incluidas bases de datos, limitada a publicaciones en inglés y español hasta 2018, usando descriptores específicos sobre el diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento del asma en la infancia.

- Publicaciones oficiales del Ministerio Sanidad, incluido el Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), y del Instituto Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria (INGESA), entidad dependiente del Ministerio de Sanidad de España que gestiona la prestación sanitaria pública de las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla, oficialmente considerada como la CA número 18. Publicaciones oficiales de las CC. AA. incluyendo sus respectivos Boletines Oficiales Autonómicos y de Ceuta y Melilla.

Revisión de páginas web:

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social, la sección correspondiente a Sanidad.

- Consejerías competentes en materia de Sanidad de las CC. AA., Ceuta y Melilla, y de sus Servicios de Salud.

- Respirar/To Breathe: página del Grupo de Vías Respiratorias (GVR) de la Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPap).

Encuesta enviada vía telemática a las direcciones de correo electrónico de contacto de las asociaciones autonómicas de PAP federadas de la AEPap, implantadas en todas las CC. AA. a excepción de Ceuta y Melilla, para las que se contactó telefónicamente con pediatras de la zona. La encuesta consistió en tres preguntas:

- El manejo del asma en la infancia/adolescencia por los pediatras de AP de su comunidad se realiza mediante un plan/guía definido, y en caso afirmativo cómo se podía acceder al mismo.

- La atención a los niños y adolescentes con asma está incluida en la CS autonómica.

- El programa informático o la historia informatizada que se emplea para el registro de la actividad clínica en la consulta de Pediatría en su CA incluye un apartado específico dónde anotar el control y seguimiento realizado a los niños y adolescentes con asma.

Explicación de las variables dicotómicas de la encuesta (sí/no):

- Plan para el manejo del asma: documento normativo elaborado mediante consenso entre profesionales que atienden niños y adolescentes con asma de la región y adaptado a las características sociales y sanitarias locales. Su función es servir de apoyo a los clínicos en el diagnóstico y manejo del asma, conforme a criterios aceptados por la comunidad científica internacional. Incluye planificación, logística, estrategia de implantación, recursos, y coordinación entre niveles asistenciales (AP y atención hospitalaria) y es apoyado por la administración pública de salud autonómica3,7.

- Guía de práctica clínica (GPC) para el manejo del asma: documento elaborado por consenso de expertos de la región con el fin de estandarizar los procedimientos diagnósticos y terapéuticos de la enfermedad según los conocimientos científicos actuales basados en la mejor evidencia y apoyado por la administración pública de salud autonómica3,7.

Ambos, planes y guías pretenden mejorar el manejo del asma disminuyendo la variabilidad interprofesional e influir positivamente en el curso de la enfermedad, por lo que a efectos prácticos se han considerado como única variable a la hora de analizar la situación actual3.

- Definición de Cartera de Servicios (CS) de AP del SNS: conjunto de servicios que responden a necesidades y demandas de la población, sustentadas en criterios científico-técnicos y en prioridades de política sanitaria. Son actividades desarrolladas por profesionales de AP, destinadas a atender o prevenir un problema de salud o satisfacer una demanda sanitaria y que han de cumplir unos criterios definidos de acreditación. La CS es un instrumento dinámico y flexible, en tiempo y ámbito geográfico (CA)9.

- Módulo específico: entendido como formulario o apartado independiente en la historia clínica informatizada de cada CA donde se registran las actividades realizadas para el control y seguimiento de los pacientes con asma, como clasificación de la enfermedad, tratamientos pautados, estudios complementarios, actividades educativas realizadas o controles programados10.

Intervención: se realizó un análisis pormenorizado del contenido de los planes de manejo del asma en las diferentes CC. AA., empleando un protocolo definido que consta de 14 ítems principales y 27 subítems, relativos a criterios diagnósticos y de tratamiento, definición de recursos disponibles, distribución y organización de tareas entre profesionales, indicadores de calidad asistencial para su evaluación y actualizaciones del documento realizadas (Tabla 1). Este protocolo se estableció de acuerdo con las GPC más recientes, las recomendaciones publicadas por el GVR de la AEPap, los documentos de CS para AP del SNS y las normas de calidad asistencial recomendadas para el manejo del asma en Pediatría de AP5,6,9,11-16.

| Tabla 1. Protocolo de estudio para la evaluación de los planes/guías de atención al niño/a y adolescente con asma y forma de aplicarlo a cada uno de ellos | |

|---|---|

| Puntos | |

| Documento escrito | 1 |

| Revisado en los últimos 5 años | 1 |

| Ámbito de actuación definido | 1 |

| Objetivos definidos | 1 |

| Criterios diagnósticos de inclusión en el programa: | |

|

0,5 |

|

0,5 |

| Clasificación de la gravedad del asma en el momento diagnóstico | 1 |

| Identificación de pacientes con asma de riesgo vital | 1 |

| Diagnóstico de alergia | 1 |

| Protocolo para el tratamiento controlador | 1 |

| Protocolo de seguimiento: | |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

|

0,14 |

| Protocolo para el manejo de la agudización del asma (crisis asmática) | |

|

0,33 |

|

0,33 |

|

0,33 |

| Educación en el asma | |

|

0,33 |

|

0,33 |

|

|

|

0,07 |

|

0,07 |

|

0,07 |

|

0,07 |

|

0,07 |

| Criterios de coordinación y derivación entre niveles asistenciales | 1 |

| Criterios de evaluación: indicadores de calidad asistencial: Registro en la historia clínica de: | |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

0,125 |

|

|

|

0,06 |

|

0,06 |

| Total | 14 |

Análisis de los datos: primero, se realizó un análisis descriptivo de las tres variables inicialmente consideradas: presencia de plan/guía de manejo del asma, inclusión en la CS autonómica y existencia de módulo informático independiente para la historia clínica de los pacientes con asma, así como la distribución de estas por CC. AA.

A continuación, se analizó el grado de adaptación del contenido de los planes al protocolo establecido y su variabilidad por CC. AA. Para ello se adjudicó un punto por cada ítem presente en el documento revisado. En caso de que un ítem tuviese subítems, se dio a cada uno un valor proporcional hasta sumar uno. El resultado se expresó como el porcentaje de puntos obtenidos sobre el total de los 14 puntos posibles (Tabla 1).

Además, se realizó un análisis individual de los 14 ítems considerados para conocer su porcentaje de cumplimentación.

RESULTADOS

Todas las asociaciones federadas de la AEPap, una por CC. AA., en total 17, contestaron a la encuesta telemática y para las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla las respuestas fueron telefónicas de forma independiente. Los pediatras consultados para Ceuta y Melilla contestaron negativamente a las tres preguntas planteadas por lo que, a efectos estadísticos, y teniendo en cuenta que ambas dependen de INGESA, fueron evaluadas conjuntamente como una CA más, con lo que para toda España se consideraron en total 18 CC. AA.

Los resultados de la primera pregunta pusieron de manifiesto la existencia de planes para el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica en nueve CC. AA. (50%), coincidiendo con la búsqueda en publicaciones y web oficiales del Ministerio de Sanidad y de las Consejerías de Sanidad de las diferentes regiones, tres (33,3%) se consideraron planes de atención al niño/adolescente con asma: Andalucía, Asturias e Islas Baleares y 6 (66,7%) guías de asma infantil: Aragón, Cantabria, Castilla y León, Cataluña, País Vasco y Madrid. En las otras 9 CC. AA. (50%) contestaron no disponer de documento autonómico oficial para el manejo de la enfermedad: Canarias, Castilla-La Mancha, Comunidad Valenciana, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Murcia, Navarra e INGESA (Ceuta y Melilla).

En relación con la pregunta sobre la inclusión de la atención al asma en infancia/adolescencia en la CS de AP de su CA, respondieron afirmativamente 10 de ellas (55,6%): Andalucía, Aragón, Asturias, Cantabria, Castilla y León, Galicia, Madrid, Murcia, Navarra y País Vasco, no figurando en las restantes 8 CC. AA. (44,4%).

Para la tercera pregunta, las que respondieron de forma afirmativa sobre la existencia de un módulo específico en la historia clínica informatizada para el registro de las actividades realizadas en los pacientes pediátricos con asma fueron 11 (61,1%) y siete comunidades (38,9%) respondieron no disponer de programa informático propio para esta patología: Andalucía, Castilla-La Mancha, Canarias, Valencia, Galicia, Extremadura e INGESA.

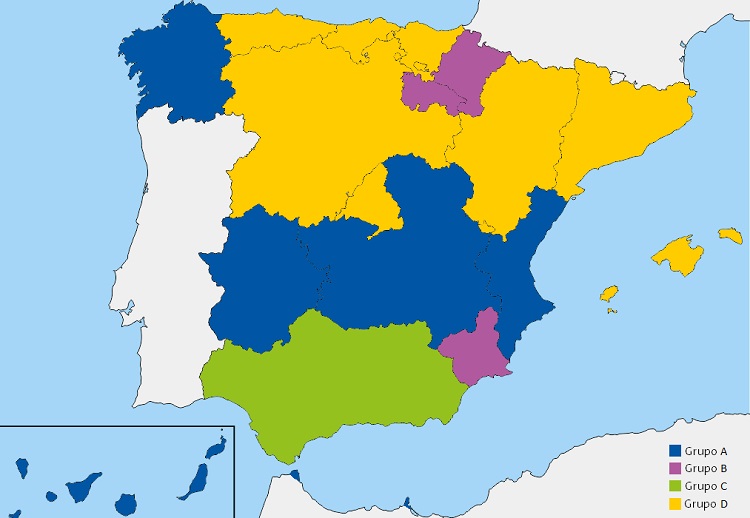

La distribución de la existencia de plan/guía para manejar el asma en edad pediátrica por CC. AA. y la inclusión de esta atención en la CS de AP permitió su clasificación cuatro grupos (Tabla 2, Fig. 1). Se utilizó la misma distribución para las variables: existencia de plan/guía y disposición de módulo informático de registro específico para el asma obteniendo otros cuatro grupos de CC. AA. (Tabla 3, Fig. 2). Aunque con alguna diferencia, las CC. AA. incluidas en cada grupo considerado fueron casi siempre las mismas.

| Tabla 2. Clasificación por grupos de las comunidades autónomas de acuerdo con la existencia de plan o guía autonómico para manejar el asma en edad pediátrica y su inclusión en la Cartera de Servicios de Atención Primaria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grupo 1 | Grupo 2 | Grupo 3 | Grupo 4 | |

| Plan o guía | No | No | Sí | Sí |

| Inclusión en cartera de servicios | No | Sí | No | Sí |

| Número (%) | 6 (33,3%) | 3 (16,7%) | 2 (11,1%) | 7 (38,9%) |

| Comunidades autónomas |

Canarias Castilla-La Mancha Extremadura INGESA (Ceuta-Melilla) Com. Valenciana La Rioja |

Galicia Murcia Navarra |

Islas Baleares Cataluña |

Aragón Asturias Cantabria Castilla y León Madrid País Vasco Andalucía |

| Figura 1. Representación gráfica de los 4 grupos de comunidades autónomas en función de la existencia de plan/guía para manejar el asma en edad pediátrica y la inclusión en su Cartera de Servicio de Atención Primaria |

|---|

|

|

Tabla 3. Clasificación por grupos de las comunidades autónomas de acuerdo con la existencia de plan o guía autonómico para el asma en edad pediátrica y la disponibilidad de módulo informático específico para el asma en la historia clínica |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grupo A | Grupo B | Grupo C | Grupo D | |

| Plan o guía | No | No | Sí | Sí |

| Programa informático | No | Sí | No | Sí |

| Número (%) | 6 (33,3%) | 3 (16,7%) | 1 (5,6%) | 8 (44,4%) |

| Comunidades autónomas |

Canarias Castilla-La Mancha Extremadura Galicia INGESA (Ceuta-Melilla) Com. Valenciana |

La Rioja Murcia Navarra |

Andalucía |

Aragón Asturias Islas Baleares Cantabria Castilla y León Cataluña Madrid País Vasco |

| Figura 2. Representación gráfica de los 4 grupos de comunidades autónomas en función de la existencia de plan/guía para manejar el asma en edad pediátrica y disponibilidad de módulo informático específico de asma en la historia clínica |

|---|

|

El análisis en conjunto de las tres variables mostró que seis CC. AA. (33,3%), Asturias, Castilla y León, Cantabria, Aragón, País Vasco y Madrid, tenían plan/guía para el manejo del asma en la edad pediátrica, esta actividad estaba incluida en la CS y los datos se registraban en un apartado informático para ello. Por el contrario, en 5 (27,8%) (Castilla-La Mancha, Canarias, Valencia, Extremadura, Ceuta y Melilla), no se disponía de plan/guía, la actividad no era incluida en la CS y no existía registro informático propio de la misma. Para el resto de las CC. AA. la distribución de las variables estudiadas fue más irregular (Tablas 2 y 3) (Figs. 1 y 2).

Los resultados obtenidos al aplicar el protocolo de estudio establecido (Tabla 1) a los nueve planes autonómicos disponibles en España para el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica se presentan en la Tabla 4, expresados como número total de puntos obtenidos por cada uno y porcentaje respecto al total.

| Tabla 4. Resultados obtenidos al aplicar el protocolo de estudio a los planes para el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica de las comunidades autónomas que los implementan | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comunidad autónoma (plan/guía) | N.º total de puntos | Porcentaje |

| Andalucía (plan) | 13,0 | 92,8% |

| Principado de Asturias (plan) | 12,7 | 90,5% |

| Castilla y León (guía) | 12,5 | 89,5% |

| Islas Baleares (plan) | 11,5 | 81,8% |

| Cantabria (guía) | 10,7 | 76,6% |

| País Vasco (guía) | 10,4 | 73,9% |

| Aragón (guía) | 9,7 | 69,3% |

| Cataluña (guía) | 9,6 | 68,6% |

| Madrid (guía) | 5,9 | 42,1% |

Andalucía dispone de dos planes de atención al asma17,18, uno de 2003 exclusivo para el ámbito pediátrico y una revisión posterior del 2012 en el que se unifica con el de adultos. Se ha considerado como base el plan de 2003 sobre el que se han realizado actualizaciones en 2012. Con un 92,8% de la puntuación total, cumple todos los ítems establecidos salvo haber sido revisado en un plazo menor a cinco años.

En el Principado de Asturias se estableció un plan19 de atención al asma en edad pediátrica en 2001, revisado en 2011. Con un 90,5% de la puntuación total, cumple todos los ítems salvo haber sido revisado en los últimos 5 años y especificar la distribución de tareas entre los profesionales.

En la comunidad de Castilla y León, su guía20 de 2004 obtiene un 89,5% del total, tampoco ha sido revisada en los últimos cinco años, no clasifica el grado de control de la enfermedad, no dispone de hoja de registro de síntomas/FEM y falta algún indicador de calidad como registrar las crisis asmáticas en la historia y un plan programado de visitas.

El plan de Islas Baleares21 de 2007 puntúa un 81,8% del total; como los anteriores no ha sido revisado en los últimos 5 años, no identifica niños con asma de riesgo vital (ARV), no dispone de protocolo validado para valorar el control y no especifica la necesidad de registrar las actividades educativas.

La guía de la comunidad de Cantabria22 de 2006 puntúa un 76,6% del total, fallando en los ítems de revisión en los últimos cinco años, tener objetivos definidos, criterios de coordinación entre niveles asistenciales, protocolo validado para valorar el control clínico y registrar las actividades educativas.

En el País Vasco existe una guía23 unificada de asma para niños, adolescentes y adultos de 2005 y una revisión posterior pediátrica de 2015. Al igual que ocurre en Andalucía y Asturias, se considera como base la de 2005 complementada con la actualización de 2015. Obtiene 73,9% del total, no puntuando en definir el ámbito de actuación, definir criterios diagnósticos, identificar pacientes con ARV, no dispone de protocolo para valorar el control y faltan más del 50% de los indicadores de calidad considerados.

La guía de Aragón24 de 2004 puntúa un 69,3% del total, no ha sido revisada en los últimos cinco años, no tiene objetivos definidos, no identifica pacientes con ARV, no dispone de protocolo para valorar el control, no especifica la necesidad de pruebas funcionales de seguimiento, no dispone de modelos de planes de tratamiento y le falta algún indicador de calidad, como el registro de crisis asmáticas o de la documentación entregada.

La guía de Cataluña25 de 2008 puntúa un 68,6% del total no habiendo sido revisada en los últimos cinco años, no presenta objetivos ni ámbito de actuación definido, no considera el grado de control del asma ni pruebas funcionales para su seguimiento, no distribuye tareas entre Pediatría-enfermería, no especifica los materiales educativos disponibles y le faltan más del 50% de los indicadores de calidad considerados.

Por último, se ha considerado como guía los documentos que aparecen dentro de la CS estandarizada de AP de Madrid26 bajo el título: Atención a niños con asma activa, actualizada en 2014. Puntúa un 42,1% del total. No tiene objetivos definidos, no identifica pacientes con ARV, no especifica la necesidad de diagnóstico de alergias, no dispone de protocolos de tratamiento, no ha sido revisada en los últimos cinco años y no hay criterios de coordinación entre niveles asistenciales. En cambio, el protocolo de seguimiento es bastante adecuado, y puntúa bien en el registro de los indicadores de calidad.

Los porcentajes de cumplimiento de los ítems estudiados en los planes evaluados se resumen en la Tabla 5.

| Tabla 5. Porcentaje de cumplimiento de los ítems estudiados en los planes para el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica de las comunidades autónomas evaluados | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ítem estudiado | Sí (%) | No (%) |

| Revisado en los últimos 5 años | 1 (11,1%) | 8 (88,9%) |

| Criterios de evaluación indicadores de calidad asistencial (completo) | 2 (22,2%) | 7 (77,8%) |

| Protocolo de seguimiento (completo) | 3 (33,3%) | 6 (66,7%) |

| Objetivos definidos | 5 (55,6%) | 4 (44,4%) |

| Identificación de los niños con asma de riesgo vital | 5 (55,6%) | 4 (44,4%) |

| Educación en el asma (completo) | 5 (55,6%) | 4 (44,4%) |

| Ámbito de actuación definido | 7 (77,8%) | 2 (22,2%) |

| Criterios de coordinación y derivación entre niveles asistenciales | 7 (77,8%) | 2 (22,2%) |

| Criterios diagnósticos de inclusión en el programa (completo) | 8 (88,9%) | 1 (11,1%) |

| Diagnóstico de la alergia | 8 (88,9%) | 1 (11,1%) |

| Protocolo de tratamiento controlador | 8 (88,9%) | 1 (11,1%) |

| Protocolo para el manejo de la agudización asmática (completo) | 8 (88,9%) | 1 (11,1%) |

| Documento escrito | 9 (100%) | - |

| Clasificación de la gravedad del asma en el momento diagnóstico | 9 (100%) | - |

Los parámetros que menos se han observado son el de haber sido revisado en los últimos cinco años, de los nueve planes solo 1 (11,1%) lo cumple, y los indicadores de calidad, que solo dos (22,2%) los incluyen todos, aunque otros cuatro puntúan por encima del 0,75. Dentro de los indicadores de calidad, los subítems que más fallan son el registro de las actividades realizadas (cuatro), de las crisis asmáticas (cuatro), de la espirometría al diagnóstico y anual (tres) y del grado de control anual (tres).

El ítem del protocolo de seguimiento lo cumplen íntegramente un 33,3% de los documentos valorados. En su mayoría les falta protocolo de valoración del control clínico del asma (55,6%). El resto de subítems los cumplen todos menos dos que no especifican realizar espirometría/FEM anual, ni aportan modelos de planes de tratamiento para las familias.

Únicamente un 55,6% (cinco) tienen criterios de identificación de niños con ARV y objetivos definidos.

El ítem de educación en el asma, si bien lo cumplen solo un 55,6% (cinco) de forma íntegra, otra guía puntúa por encima del 0,9.

Un 77,8% de los documentos (siete) define el ámbito de actuación, los criterios de coordinación y derivación entre niveles asistenciales.

Un 88,9 % de los planes (ocho) tienen criterios diagnósticos claros de inclusión en el programa y en todos los documentos, salvo la guía de Madrid se contempla la necesidad de pruebas diagnósticas de alergia como parte del proceso asistencial y se adjuntan protocolo de tratamiento controlador y del manejo de agudizaciones.

El 100% tienen documento escrito y contemplan la clasificación de la gravedad del asma al diagnóstico.

DISCUSIÓN

El asma es posiblemente la enfermedad crónica más frecuente en la edad pediátrica en España. No solo son relevantes los aspectos relacionados con la prevalencia de la enfermedad, sino también los que tienen que ver con la afectación de la calidad de vida del niño y de su familia, con la repercusión en la economía nacional, a nivel de gasto sanitario, y con el consumo de recursos asistenciales1. El control del asma persigue disminuir su impacto en la población para lo que es preciso organizar su atención adecuando los recursos sanitarios, humanos y materiales a las necesidades asistenciales y conseguir implicar y capacitar a los profesionales involucrados4,11,12.

Por otra parte, las principales GPC del asma, plantean la necesidad de organización de la asistencia, pero no desarrollan la totalidad de los puntos clave necesarios para ponerla en marcha, quizá debido a que están dirigidas a muchos entornos y no pueden recoger las peculiaridades de cada sistema sanitario, ni definir un modelo único de organización para la atención del asma en Pediatría.

En España, por las características de su SNS los niños y adolescentes con asma consultan en primer lugar con los pediatras de AP y estos son los profesionales mejor situados para el diagnóstico y seguimiento de la enfermedad. Por ello, desde el inicio de los años 90 han ido surgiendo modelos organizativos de atención al asma basados en la AP, incluyendo al pediatra y al profesional de enfermería5,6 y que han ido ampliando su ámbito de actuación hasta el desarrollo de programas integrales de manejo de la enfermedad de base autonómica. Sin embargo, como indican los resultados de este trabajo, la implementación de estos ha sido muy desigual por CC. AA. ya que si bien la atención al asma en la edad pediátrica se ha incluido dentro de las CS comunes para AP del SNS8 las transferencias sanitarias a las CC. AA. han conllevado enfoques distintos en los servicios sanitarios ofertados por cada una de ellas9.

A pesar de que los planes integrales con seguimiento clínico regular de pacientes asmáticos son claramente coste-efectivos, disminuyendo visitas a urgencias y hospitalizaciones y mejorando su calidad de vida y la de sus familiares1,7, solo el 50% de las 18 comunidades dispone de un plan o guía regional para atender el asma en la edad pediátrica. Además, las que tienen implantados estos programas, destinan mayor número de recursos humanos y materiales para su manejo que aquellas que no los tienen3. Si bien, algunos estudios reflejan que la existencia de planes no asegura su conocimiento ni su puesta en práctica por parte de los profesionales implicados3,15,16. En este caso, todas las asociaciones cuyas CC. AA. tenían implantados planes de manejo del asma los conocían y aportaron el documento de trabajo, pero al no haber realizado una encuesta personal no es posible conocer su difusión entre los pediatras de AP. Por ello, para facilitar la implementación y la adherencia a los mismos no solo es necesario el documento de recomendaciones, sino también planificar la formación de los profesionales y la disposición de recursos humanos y materiales. Así mismo, es fundamental disponer de indicadores de calidad que justifiquen su inclusión en la CS de AP de la CA y permitan una evaluación periódica del programa3,9.

En general, la existencia de un plan o guía de asma en gran parte de las CC. AA. se ha acompañado de la inclusión de esta actividad en su CS y para el desarrollo del mismo, de la implementación de un programa informático de registro. Así, de las nueve comunidades con planes de manejo del asma la edad pediátrica en siete esta atención se incluye en la CS de AP, lo que supone un reconocimiento de las actividades desarrolladas por los pediatras de AP9. Solo en tres de las nueve CC. AA. sin planes incluyen esta actividad en sus CS, en ellas es posible que la atención a esta patología siga GPC nacionales o internacionales11,12 permitiendo, en parte, cumplir con los criterios de calidad establecidos por el SNS9.

Con excepción de Andalucía, las otras ocho comunidades con planes para el manejo del asma en la infancia tienen también programa informático especialmente diseñado para los profesionales de los centros de AP e incluido en la historia clínica informatizada. Este registro permite el seguimiento del niño con asma, facilita la labor educativa del profesional con la posibilidad de la entrega en cada visita de consejos e instrucciones para el niño y la familia y es útil en la revisión y evaluación periódica de los objetivos previstos. Por el contrario, solo tres comunidades sin planes tienen módulo informático de registro del seguimiento del asma en la edad pediátrica.

En el Real Decreto 1030/2006, del 15 de septiembre, se establece la cartera de servicios comunes del SNS; tanto en este decreto como en actualizaciones posteriores8-10, la detección y seguimiento del niño con patologías crónicas, entre ellas el asma, está incluido en la CS básica de AP, y siendo conocidos los beneficios de disponer de un plan de atención al niño y adolescente con asma de base autonómica, en este momento, el 50% de las CC. AA. no disponen de un protocolo de consenso regional entre los profesionales implicados. Si bien en alguna de esas CC. AA., se han publicado programas de atención al asma en la infancia de ámbito más limitado como el Protocolo para el Manejo del Asma del Complejo Hospitalario Insular Materno-Infantil de Gran Canaria27, estos no han sido valorados en este trabajo al no ser de base regional.

De los nueve documentos encontrados y analizados 3 (33,3%) fueron considerados planes de atención, mientras que los seis restantes (66,7%) se adecuaron mejor al concepto de guía. Esta asignación se realizó teniendo en cuenta que un plan de atención a una patología crónica, en este caso el asma, difiere de una guía en que supone un abordaje integral de la misma con identificación de la situación inicial y los recursos disponibles, en función de lo que define unos objetivos claros e indicadores calidad que permitan su evaluación. Incluye protocolos, documentos pertinentes y un plan de implementación. En cambio, una guía describe el manejo óptimo del asma en consonancia a la mejor evidencia científica pero no tiene la obligación de tener en cuenta los recursos disponibles, ni llevar asociado plan de difusión y puesta en marcha3,7.

De acuerdo con los resultados obtenidos al valorar la adecuación de los documentos sobre el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica por CC. AA., los considerados planes, implantados en Andalucía17,18, Asturias19 e Islas Baleares21, sobresalen en puntuación global sobre las guías, ocupando los primeros lugares de la clasificación, lo que supone un mayor grado de adecuación a las recomendaciones publicadas al respecto5,11-14. Esta superioridad puede explicarse en parte debido a que el protocolo aplicado está diseñado para planes e incluye ítems (definición de ámbito de actuación y objetivos, o indicadores de calidad) que por definición contemplan los planes, pero no necesariamente las guías. Además de puntuar mejor en el protocolo, la evidencia disponible hasta la fecha apunta a que el uso de planes obtiene mejores resultados a la hora de ser implementados que el de las guías7, así un estudio que evaluó la calidad de las guías de práctica clínica constató puntuaciones bajas en la evaluación del grado de seguimiento de las mismas28. En general, los planes procuran adaptar los documentos haciéndolos de fácil manejo para los profesionales, facilitando su difusión y aceptación5, punto que, aunque no se ha tenido en cuenta en el protocolo de valoración, con frecuencia no adoptan las guías, ejemplo de ello podría ser la guía del País Vasco23, presentada en formato extenso, poco intuitivo y práctico, suponiendo un obstáculo a su difusión y puesta en práctica entre profesionales sanitarios.

Los planes de atención al asma en edad pediátrica que mejor han puntuado son los de Andalucía y Asturias17-19, muy completos, si bien cabe resaltar su falta de actualización en los últimos cinco años. Por otro lado, tienen a favor los más de 15 años de experiencia desde su puesta en marcha y haber servido como modelo para planes y guías posteriores20-22,24. Habría que remarcar como aspecto positivo, el formato breve y de fácil lectura en el que se ha publicado la revisión de 2011 del plan de Asturias19, en consonancia con las propuestas del GVR de la AEPap5. En el mismo sentido, resaltar lo bien organizado y estructurado que está el seguimiento de los pacientes, la distribución de tareas entre profesionales y la educación en el asma del tercer plan valorado el de Islas Baleares21.

Entre las guías revisadas, la implementada en Castilla y León20 sigue muy de cerca a los planes de Asturias y Andalucía en puntuación global, superando incluso al plan de Islas Baleares, siendo la más completa, de lectura amistosa y fácil manejo. Si bien se echan en falta hojas de registro de síntomas y la clasificación del asma en función del control, así como algunos indicadores de calidad de la asistencia, probablemente como consecuencia de haber sido considerada en su origen, más una guía, que un auténtico plan. En el otro extremo, con la puntuación más baja, encontramos la de la Comunidad de Madrid26, pero hay que tener en cuenta que, a pesar de haberla considerado como guía, en realidad es un “documento de atención a los niños con asma activa”, elaborado con el fin de unificar procesos diagnósticos y terapéuticos del asma en Pediatría en dicha comunidad dentro de su CS de AP, por ello no puntúa en muchos de los ítems considerados.

En cuanto al análisis individualizado de los parámetros incluidos en el protocolo, llama la atención que de los nueve documentos evaluados únicamente la guía del País Vasco23 haya sido revisada en los últimos cinco años. Mientras las guías GINA11 y GEMA12 se actualizan anualmente, la Guía Británica29, por ejemplo, se actualiza cada 2-3 años. En la revisión bibliográfica realizada no se ha encontrado referencia alguna sobre cada cuanto tiempo sería recomendable revisar y actualizar los planes, pero parece lógico pensar que actualizaciones frecuentes, de acuerdo con las principales guías internacionales serían apropiadas, aunque estas modificaciones no necesariamente tuviesen que abarcar a todo el plan.

Otros ítems que pocos planes cumplen íntegramente son aquellos compuestos por varios subítems, ya que deben cumplir más premisas para obtener el punto entero y esto complica su interpretación. Es el caso de los indicadores de calidad, únicamente dos planes obtienen el punto entero incluyendo los ocho indicadores considerados, si bien en otros 4 figuran más del 75% de los mismos. Además, esta baja cumplimentación podría responder a que la mayoría de los documentos analizados no son planes, sino guías en las que estos indicadores de calidad no suelen ser considerados3,7. También podría justificarse en relación con que la guía GEMA hasta su versión 4.2 de 201712 no incluyó criterios de calidad asistencial, siendo la mayoría de los documentos analizados previos a esa fecha. Actualmente, se están intentando desarrollar indicadores de calidad, que una vez validados, ayuden a medir su correcta aplicación y los resultados en salud de estos. Así, distintos trabajos han ido proponiendo normas de buena práctica clínica, en general basados en consenso de expertos13,14, y algunos de ellos son los que han sido incluidos en el protocolo de evaluación. La aplicación de estos indicadores de calidad en las regiones con planes ayudaría a medir su impacto, por ejemplo, en la calidad de vida de los pacientes y sus familias, en el consumo de recursos derivado de consultas, visitas a urgencias e ingresos, así como a conocer la fidelización de los sanitarios y sus posibles mejoras3,14.

El protocolo de seguimiento es otro de los puntos con menor grado de cumplimentación, únicamente tres planes lo cumplen íntegramente. En su mayoría fallan al no figurar un protocolo validado para el control clínico del asma (55,6%), aspecto que desde hace años recomiendan la GINA11 y la GEMA12, y que sería conveniente integrar en los planes de atención al asma dentro de la historia clínica.

Únicamente cinco de los nueve planes incluyen criterios para identificar pacientes con ARV. Las principales GPC11,12,29 recomiendan la identificación de factores que predisponen a ARV, ya que a pesar de ser un grupo minoritario de pacientes (los escasos datos epidemiológicos en España lo sitúan en torno al 3% de las exacerbaciones asmáticas30), tienen mayor riesgo de sufrir una crisis de rápida instauración y resultado fatal. El reconocimiento de estos pacientes, su control estrecho y la educación en cuanto al manejo de su asma y prevención de las crisis han conllevado resultados favorables en su pronóstico por lo que sería recomendable que los planes de atención incluyesen un apartado para su identificación30.

Otro ítem que cumplen cinco de los nueve planes es el de tener objetivos definidos, una vez más este dato puede ir en relación a las diferencias antes comentadas entre planes y guías3,7. Así, todos los planes analizados cumplen este parámetro, mientras que de las guías únicamente lo cumplirían dos de las seis estudiadas.

La educación en asma es otro punto con múltiples subítems; cinco planes lo cumplen íntegramente y otros dos cumplen más del 90%, pero todos ellos dedican un amplio apartado a la educación, concordando con la idea de que representa un pilar fundamental en el tratamiento del asma20,21.

Otros parámetros como contemplar la clasificación de la gravedad del asma en el momento diagnóstico, tener documento escrito, criterios diagnósticos claros de inclusión en el programa, ámbito de actuación definido, criterios de coordinación y derivación entre niveles asistenciales o protocolos de tratamiento controlador y de las agudizaciones, los cumplen la mayoría de los planes, probablemente debido a que son los criterios definidos en el Servicio de Atención al Asma Infantil incluido dentro del apartado de Atención al Niño de la CS para AP del Ministerio de Sanidad y cuya cumplimentación es necesaria para conseguir la acreditación de dicha atención9.

Los últimos 20 años en España se han ido publicando planes autonómicos para el manejo del asma en edad pediátrica. Los escasos trabajos que analizan los resultados de la puesta en marcha de los mismos5 han puesto de manifiesto que las comunidades con plan/guía para el asma en Pediatría tienen más recursos y un mayor porcentaje de niños con asma son seguidos en las consultas de Pediatría de AP, aunque se desconoce la repercusión de esta atención en la calidad de vida de los pacientes y sus familiares o en el consumo de recursos, así como si existen diferencias entre CC. AA. con plan implantado, las que tienen guía y aquellas que no tienen ninguno3. Las experiencias publicadas en otros países como Finlandia, Polonia, Canadá y Australia en los que se instauraron planes regionales o nacionales de atención al asma, han evidenciado que son programas claramente coste-efectivos para los pacientes y la sociedad en general. Además, los planes regionales/nacionales obtienen mejores resultados que las guías convencionales de asma7. Así, en una reciente “Carta mundial para todos los niños con asma”31 se propone una hoja de ruta para mejorar la calidad de vida de los niños con esta patología en la que el control y seguimiento del asma en la infancia se realice con un plan de cuidados adaptado a las peculiaridades de cada comunidad/región, basado en la AP, y siendo necesario implicar a los gobiernos, las instituciones y el personal sanitario en su implementación si se quieren mejorar sus resultados en salud.

CONCLUSIONES

El presente trabajo ha puesto de manifiesto que en España hay una gran variabilidad en la atención al asma en edad pediátrica y ha permitido elaborar un mapa por CC. AA. en relación con el empleo de planes para su manejo. Con el fin de garantizar la equidad en la atención de todos los niños y adolescentes con esta patología sería conveniente que todas las regiones dispusiesen de un plan integral de atención actualizado, basado en las características propias de cada una de ellas, adaptado a las recomendaciones de las mejores GPC, que integre a todos los profesionales encargados de la atención al asma en la infancia y adolescencia e incorpore indicadores de calidad asistencial validados y comunes que permitan establecer la pertinencia de estos planes, conocer y comparar resultados en salud y evaluar sus posibilidades de mejora.

CONFLICTO DE INTERESES

Este documento forma parte del trabajo de fin de máster realizado como parte del Máster de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Las autoras declaran no tener conflictos de intereses en relación con la preparación y publicación de este artículo.

ABREVIATURAS

AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria · AP: Atención Primaria · ARV: asma de riesgo vital · CA/CC. AA.: comunidad autónoma/comunidades autónomas · CS: cartera de servicios · GPC: guía de práctica clínica · GVR: Grupo de Vías Respiratorias de la AEPap · PAP: Pediatría (pediatras) de Atención Primaria · SNS: Sistema nacional de salud.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- García Merino A, Praena Crespo M. El impacto del asma en la infancia y la adolescencia. En: AEPap (ed.). Curso de actualización en Pediatría 2013. Madrid: Exlibris Ediciones; 2013. p. 257-65.

- Blasco Bravo AJ, Pérez Yarza EG, Lázaro y de Mercado P, Bonillo Perales A, Díaz Vázquez CA, Moreno Galdó A. Coste del asma en Pediatría en España: un modelo de evaluación de costes basado en la prevalencia. An Pediatr (Barc). 2011;74:145-53.

- Úbeda Sansano MI, Cano Garcinuño A, Rueda Esteban S, Praena Crespo M. Resources to handle childhood asthma in Spain: The role of plans and guides and the participation of nurses. Allergol Immunopathol. 2018;46:361-9.

- Sordo MA, Alonso JC, Del Ejido J, Díaz CA, Alonso LM, García MT. Evaluación de las actividades y de la efectividad de un programa del niño asmático desarrollado en Atención Primaria. Aten Primaria. 1997;19:199-206.

- Implantación en España de los programas de atención al niño con asma. Situación actual y propuestas del Grupo de Vías Respiratorias. En: Grupo de Vías Respiratorias de la AEPap (GVR-AEPap) [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.respirar.org/index.php/grupo-vias-respiratorias/grupo-vias-respiratorias

- Díaz Vázquez CA. Mesa Redonda. Asma ¿En qué situación estamos? Organización de la asistencia sanitaria a los niños con asma. Bol Pediatr. 2003;43:191-200.

- Selroos O, Kupczyk M, Kuna P, Łacwik P, Bousquet J, Brennan D, et al. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:474-83.

- Real Decreto 1030/2006, de 15 de septiembre, por el que se establece la cartera de servicios comunes del Sistema Nacional de Salud y el procedimiento para su actualización. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. BOE-A-2006-16212. En: Boletín Oficial del Estado [en línea] [consultado 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2006/09/15/1030/con

- Instituto de Información Sanitaria – Sistema de Información de Atención Primaria (SIAP). Cartera de servicios de Atención Primaria. Desarrollo, organización, usos y contenido. En: Sistema Nacional de Salud [en línea] [consultado el consultado 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/siap/Cartera_de_Servicios_de_Atencion_Primaria_2010.pdf

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad, Instituto de Información Sanitaria - Subcomisión de Sistemas de Información del SNS. Oferta de Servicios en Atención Primaria. Servicios asistenciales, procedimientos y acceso a pruebas diagnósticas. En: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/equidad/informeAnual2008/annualReportSNS2008ING.pdf

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention [Internet]; Updated 2020 [en línea] [consultado 07/05/2020]. Disponible en https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GINA-2020-full-report-final-wms.pdf

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía Española para el Manejo del Asma. En: GEMA 5.0 2020 [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.gemasma.com

- Quirce S, Delgado J, Entrenas LM, Grande M, Llorente C, López Viña A, et al. Quality Indicators of Asthma Care Derived From the Spanish Guidelines for Asthma Management (GEMA 4.0): A Multidisciplinary Team Report. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2017;27:69-73.

- Ruiz Canela Cáceres J, Aquino Linares N, Sánchez Díaz JM, García Gestoso ML, de Jaime Revuelta ME, Praena Crespo M. Indicators for childhood asthma in Spain, using the Rand method. Allergol Immunopathol. 2015;43:147-56.

- Plaza V, Rodríguez del Río P, Gómez F, López Viña A, Molina J, Quintano JA, et al. Identificación de las carencias asistenciales en la atención clínica del asma en España. Resultados de la encuesta OPTIMA-GEMA. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2016;39:181-201.

- Plaza V, Bolívar I, Giner J, Llauger MA, López Viña A, Quintano JA, et al. Opinión, conocimientos y grado de seguimiento referidos por los profesionales sanitarios españoles de la Guía Española para el Manejo del Asma (GEMA) Proyecto GEMA-TEST. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008;44:245-51.

- Lora Espinosa A, Fernández Carazo C, Jiménez Cortes A, Martín Vázquez C, Pérez Frías J, Pérez Martín AF, et al. Guía de diseño y mejora continua de procesos asistenciales. Asma en la edad pediátrica. En Consejería de Salud. Junta de Andalucía [en línea] [consultado e. 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.epes.es/wp-content/uploads/Asma-en-la-edad-pediatrica_definitivo.pdf

- García Polo C, Gómez-Pastrana Duran D. Proceso Asistencial Integrado de Asma. Consejería de Salud. En: Junta Andalucía [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/salud_5af1956d56097_asma.pdf

- Carvajal Urueña I, García Merino A, García Muñoz M, Díaz Vázquez C, Domínguez Aurrecoechea B. Plan Regional de Atención al Niño y Adolescente con Asma del Principado de Asturias (PRANA). Servicio de publicaciones del Gobierno Principado de Asturias; 2001. Actualización 2011: Carvajal Urueña I, Cobo Ruisánchez A, Mora Gandarillas I, Pérez Vaquero A, Rodríguez García J. Plan Regional de Atención al Niño/a y Adolescente con Asma del Principado de Asturias (PRANA). En Respirar [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.respirar.org/images/pdf/respirar/prana_2011.pdf

- Asma Infantil: Guía para la atención de los niños y adolescentes con Asma de Castilla y León.. En: Junta de Castilla y León [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022] Disponible en www.respirar.org/images/pdf/respirar/asma_sacyl.pdf

- Amengual E, Botey A, Figuerola J, Herreros S, Hervás J, Carrión MT, et al. Plan de Asma Infantil de las Illes Balears. En: Conselleria de Salut i Consum del Govern de Les Illes Balears [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.ibsalut.es/apmallorca/attachments/article/1258/Plan%20de%20asma%20infantil%20de%20las%20Illes%20Balears%202007%20CAST.pdf

- Bercedo Sanz A, Gómez Serrano M, Redondo Figuero C, Martínez Herrera B, Rollán Rollán A. Guía Clínica de Manejo del Asma Bronquial en Niños y Adolescentes de Cantabria en Atención Primaria. Servicio Cántabro de Salud [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.respirar.org/images/asma_cantabria.pdf

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Asma Infantil. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Asma Infantil. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. 2014. Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS. En: Guía Salud [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en https://portal.guiasalud.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/GPC_548_Asma_infantil_Osteba_compl.pdf

- Atance Melendo E, Boné Calvo J, Castillo Laita JA, Cenarro Guerrero T, Elfau Mairal M, Forés Calata A, et al. Atención al niño asmático. En: Servicio Aragonés de Salud; Gobierno de Aragón [en línea] [consultado 20/06/2020]. Disponible en www.aragon.es/estaticos/GobiernoAragon/Organismos/ServicioAragonesSalud/Documentos/ATENCIoN+NInO+ASMATICO.PDF

- Alba Moreno F, Buñuel Álvarez C, FosEscriva E, Moreno Galdo A, Oms Arias M, Puig Congost M. Asma Infantil. Guies de práctica clínica i material docent, num. 13. Barcelona: Institut Català de la Salut [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en http://canalsalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/_A-Z/A/asma/enllasos/guia_asma_infantil.pdf

- Cartera de Servicios Estandarizados de Atención Primaria de Madrid. En: Servicio Madrileño de Salud [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en https://www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/doc/sanidad/prim/2018_cartera_de_servicios_estandarizados_ap.pdf

- Protocolo para el Manejo del Asma en Atención Primaria Coordinación entre niveles asistenciales de Atención Sanitarias del Área de Salud de Gran Canaria. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular-Materno Infantil. En: Servicio Canario de Salud [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.sepexpal.org/download/protocolos/Protocolo-Manejo-del-Asma-en-Atencion-Primaria.pdf

- Acuňa Izcaray A, Sánchez Angarita E, Plaza V, Rodrigo G, Montes de Oca M, Gich I, et al. Quality assessment of asthma clinical practice guidelines: a systematic appraisal. Chest. 2013;144:390-7.

- Asthma Guidelines. BTS/SIGN Asthma Guideline: 2016. En: British Thoracic Society [en línea] [consultado el 07/01/2022]. Disponible en www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

- Pereira Vega A, Muñoz Zara P, Ignacio Barrios VM, Ayerbe-García R. Manejo de la agudización asmática. Asma de riesgo vital. En: Soto-Campos JG (ed.). Manual de diagnóstico y terapéutica en neumología. 3.ª edición. Madrid: Ergon; 2016. p. 389-98.

- Szefler SJ, Fitzgerald DA, Adachi Y, Doull IJ,. Fischer GB, Fletcher M, et al. A worldwide charter for all children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonology. 2020;55:1282-92.