Vol. 14 - Num. 55

Originales

Factores de riesgo de complicaciones y duración del ingreso hospitalario en pacientes con tos ferina

Enrique Villalobos Pintoa, Julián Martínez-Villanuevab, Julia Cano Fernándezb, Patricia Flores Péreza, Marciano Sánchez Baylec

aSección de Pediatría Hospitalaria. Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús. Madrid. España.

bServicio de pediatría hospitalaria. Hospital Universitario Niño Jesús. Madrid. España.

cPediatra. Fundación para la Investigación, Estudio y Desarrollo de la Salud Pública. Madrid. España.

Correspondencia: E Villalobos. Correo electrónico: evillalobospinto@yahoo.es

Cómo citar este artículo: Villalobos Pinto E, Martínez-Villanueva J, Cano Fernández J, Flores Pérez P, Sánchez Bayle M. Factores de riesgo de complicaciones y duración del ingreso hospitalario en pacientes con tos ferina. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2012;14:207-15.

Publicado en Internet: 04-10-2012 - Número de visitas: 36470

Resumen

Objetivo: analizar a los niños ingresados con el diagnóstico de tos ferina en nuestro centro en el periodo estudiado y la relación de su evolución con diferentes datos clínicos, analíticos y/o epidemiológicos.

Material y métodos: estudio retrospectivo de los pacientes ingresados en nuestro centro con diagnóstico de tos ferina en el periodo 2008-2011. Se incluyen en el estudio los casos que cumplen los criterios establecidos por los Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Resultados: se estudian 85 pacientes (54,8% niñas) con una edad media de 2,04 meses. El tiempo medio de ingreso hospitalario fue de 7,44 días. Se encontró relación en la regresión lineal múltiple entre la duración del ingreso con el porcentaje de cayados (p=0,006), proteína C reactiva (PrCR) (p=0,001), saturación de oxígeno al ingreso (p=0,019), apnea (p<0,001) y cianosis (p=0,007). La tasa de ingresos aumentó progresivamente desde el año 2008.

También se objetivó asociación entre la presencia de complicaciones y el porcentaje de cayados (p=0,026), saturación de oxígeno al ingreso (p=0,001), no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna (p=0,007), oxigenoterapia (p=0,001), síntomas catarrales (p=0,017), apnea (p<0,001), cianosis (p=0,05) y coinfección con virus (virus respiratorio sincitial y/o adenovirus; p=0,044).

Fallecieron dos pacientes (letalidad, 2,4%). Se observó relación en la regresión logística entre la mortalidad y el número de leucocitos (p=0,016), neutrófilos (p=0,016), linfocitos (p=0,016), cayados (p=0,001), PrCR (p=0,039) y procalcitonina (p=0,023) al ingreso.

Conclusiones: la presencia de apnea y cianosis al comienzo del cuadro clínico, así como no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna DTPa y mayores niveles de PrCR en el momento del ingreso pueden ser consideradas factores de riesgo mayor duración del ingreso hospitalario por tos ferina.

El mayor porcentaje de cayados y nivel de procalcitonina, así como menor saturación de oxígeno, en el momento del ingreso; no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna DTPa; la presencia de síntomas catarrales, apnea y cianosis en el comienzo del cuadro y la coinfección por virus respiratorios se pueden considerar factores de riesgo de la aparición de complicaciones durante el ingreso hospitalario.

Palabras clave

● Complicaciones ● Hospitalización ● TosferinaINTRODUCCIÓN

La tos ferina es una infección respiratoria aguda endémica causada por Bordetella pertussis. Es una infección muy contagiosa con tasas de transmisión de casi el 100%, por contacto directo con las secreciones de las mucosas de las vías respiratorias de personas infectadas o a través de inhalación de las gotas que se diseminan con la tos1,2.

La mortalidad estimada en nuestro medio es menor del 1%. El 84% de la mortalidad se produce en menores de seis meses. Se consideran factores de riesgo para un peor pronóstico: lactante menor de dos meses, sexo femenino, leucocitosis y neumonía de presentación inicial, ventilación mecánica indicada por neumonía y desarrollo de hipertensión pulmonar3,4.

El diagnóstico se basa en la definición de caso de tos ferina de los Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)5:

- Caso clínico: tos de dos semanas de duración con alguno de los siguientes síntomas: tos paroxística, gallo inspiratorio o vómito tras la tos y ausencia de otra causa aparente.

- Caso confirmado: caso clínico y cultivo positivo de secreciones nasofaríngeas, detección de ADN mediante reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR) o seroconversión positiva; caso clínico ligado directamente a un caso confirmado6-8.

- Caso probable: caso clínico y seroconversión positiva.

El aislamiento de un virus no excluye el diagnóstico.

El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es analizar a los niños ingresados con el diagnóstico de tos ferina en nuestro centro en el periodo estudiado y la relación de su evolución con los diferentes datos clínicos, analíticos y/o epidemiológicos.

MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS

Se llevó a cabo un estudio transversal, descriptivo y retrospectivo.

De 95 pacientes ingresados con diagnóstico de tos ferina en nuestro hospital entre los años 2008 y 2011, se seleccionaron 85 que cumplían los criterios establecidos por el CDC para ser considerados casos confirmados. Para obtener la información de los casos de tos ferina ingresados se utilizó el Registro del Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos al Alta Hospitalaria y Cirugía Ambulatoria (CMBD).

Se recogieron los siguientes datos de los pacientes incluidos en el estudio, a partir de los informes clínicos contenidos en la intranet de nuestro hospital:

- Datos demográficos (edad, sexo).

- Datos epidemiológicos (vacunación con DTPa y número de dosis, casos en la familia, días de ingreso hospitalario, mortalidad).

- Datos clínicos (presencia de síntomas, complicaciones, ingreso en Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos [UCI], procedimientos relevantes, tratamiento y duración, tratamientos previos).

- Datos analíticos (leucocitos, neutrófilos, linfocitos, plaquetas, cayados, proteína C reactiva [PrCR], procalcitonina [PCT] al ingreso y en control posterior, PCR, cultivo y serología para B. pertussis).

Se han definido las posibles complicaciones que pueden aparecer en el transcurso de la enfermedad, como:

- Respiratorias: apnea, neumonía, neumotórax, otitis media aguda, enfisema subcutáneo.

- Neurológicas: crisis convulsivas, hemorragias cerebrales y encefalopatía.

- Otras: anergia y reactivación tuberculosa, fracturas costales, desnutrición, hipoglucemia, hiponatremia (SIADH), bronquiectasias.

Todo el estudio estadístico se realizó con el programa SPSS®, versión 15.0 para Windows®. Para el estudio de las variables cuantitativas se utilizaron las pruebas U de Mann-Whitney, W de Wilcoxon y Correlación de Pearson. Para el estudio de las variables cualitativas se utilizaron porcentajes y tablas de contingencia de 2 x 2, con determinación de X2 y odds ratio. Para completar el estudio también se utilizaron regresión logística binaria y regresión lineal múltiple paso a paso partiendo del modelo máximo y se calculó el área bajo la curva del modelo para la variable complicaciones.

RESULTADOS

La edad media fue de 2,04 meses, con una desviación típica de 1,44, con el valor mínimo de 21 días y máximo de 13 meses, siendo el 54,8% mujeres y el 45,2% restante varones. El tiempo medio de ingreso hospitalario fue de 7,44 días, con una desviación típica de 6,74, con el valor mínimo de 1 y máximo de 40 días.

Un 25% de los pacientes fue ingresado en el año 2008, un 19% en el año 2009, un 27,4% en el año 2010 y el restante 28,6% en el primer semestre del año 2011. En el año 2008, el 0,24% de los ingresos producidos en nuestro hospital se debió a casos de tos ferina; en el año 2009, fue el 0,18% y en el año 2010, el 0,26% de todos los ingresos realizados.

El 40,5% de los pacientes había recibido las dosis de vacuna correspondientes a su edad. Un 38,2% había recibido una dosis de vacuna, un 1,2% había recibido dos dosis de vacuna, y otro 1,2%, tres dosis de vacuna. El restante 59,5% no había recibido ninguna dosis.

En el 1,2% de los casos se obtuvo un cultivo positivo para B. pertussis, en un 64,3% no se realizó cultivo y en el resto el resultado fue negativo. En el 4,8% de los casos se obtuvo una serología positiva, en el 81% de los pacientes no se realizó y en el resto fue negativa.

El 47,6% de los pacientes presentó algún tipo de complicación, precisando oxigenoterapia el 65,9% del total de pacientes; ingreso en UCI, el 29,3%; ventilación mecánica, el 15,9%, y leucoaféresis, el 1,2%.

En el 44,6% de los casos había algún familiar con historia de tos prolongada y en el 7,2% existía un caso confirmado de tos ferina en la familia.

En cuanto a los síntomas y signos, la tos se encontraba presente en el 98,8% de los pacientes, gallo inspiratorio en el 35,7%, fiebre en el 14,3%, síntomas catarrales en el 44%, vómitos en el 32,1%, apnea en el 31% y cianosis en el 81%.

En el 10,7% de los pacientes existía coinfección con algún virus respiratorio (virus respiratorio sincitial [VRS], adenovirus).

En el 2,4% de los casos, el episodio terminó en éxitus.

El 7,1% de los pacientes había realizado previamente tratamiento con algún antibiótico.

Al ingreso, según los rangos de normalidad establecidos en nuestro centro, el 65,5% de los pacientes presentaba leucocitosis (>15 000 leucocitos); solo el 1,2%, hiperleucocitosis (>100 000 leucocitos); el 6%, neutrofilia (>8500 neutrófilos); el 51,2%, linfocitosis (>12 000 linfocitos); el 85,7%, trombocitosis (>400 000 plaquetas); el 3,6% presentaba una PrCR>3 mg/dl y el 1,2% presentaba una PCT>0,6 ng/ml, sugerentes de posible infección bacteriana; los pacientes presentaban una media de 0,47% de cayados, con una desviación típica de 1,21, con un valor mínimo de 0 y máximo de 7.

En la analítica de control durante el ingreso, el 23,8% presentaba leucocitosis, pero ningún paciente tenía hiperleucocitosis; el 6% presentaba neutrofilia; el 1,2%, neutropenia (<1500 neutrófilos); el 20,2%, linfocitosis; el 29,8%, trombocitosis; el 4,8% de los pacientes presentaba una PrCR>3 mg/dl y el 1,2%, una PCT>0,6 ng/ml; los pacientes presentaban una media de 1,04% de cayados, con una desviación típica de 3,14, con un valor mínimo de 0 y máximo de 14.

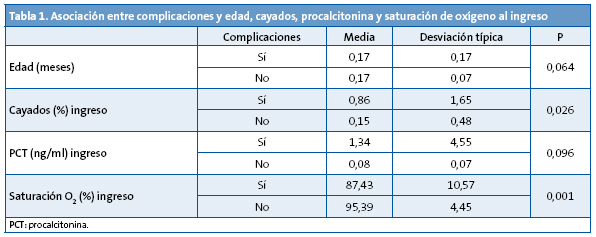

Se encuentra asociación entre la presencia de complicaciones y el porcentaje de cayados y la saturación de oxígeno al ingreso (Tabla 1).

De los 85 pacientes estudiados, 39 presentaron complicaciones durante la evolución de su enfermedad, con los siguientes resultados: el 56% eran niñas y el resto eran niños; solo el 22% había recibido alguna dosis de vacuna DTPa; el 84% necesitó oxigenoterapia durante el ingreso; en el 51% existía algún familiar con tos de larga evolución pero solo en el 8% había algún caso confirmado de tos ferina en la familia; en cuanto a los síntomas, el 100% presentaba accesos de tos, el 27% presentaba gallo inspiratorio, el 14% tuvo fiebre, el 57% padeció síntomas catarrales, el 35% tuvo vómitos, el 54% tuvo pausas de apnea y en el 89% la tos llegó a ser cianosante; en el 19% se objetivó coinfección por algún virus respiratorio; solo el 3% había tomado tratamiento antibiótico previamente.

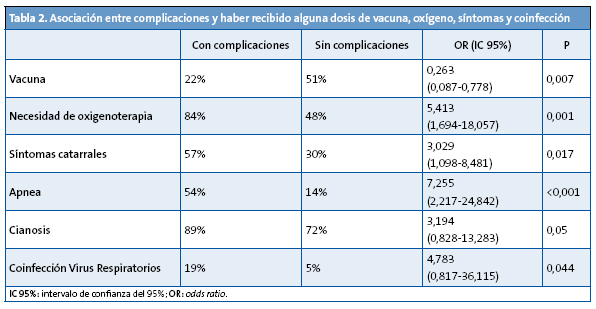

Se encuentra relación entre la presencia de complicaciones y no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna, la necesidad de oxigenoterapia, la presencia de síntomas catarrales, apnea, cianosis y coinfección con virus respiratorios (Tabla 2).

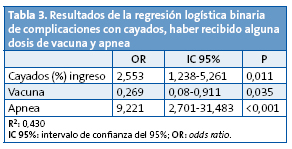

En la regresión logística binaria permanecen solo como significativos el porcentaje de cayados al ingreso, el no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna y la presencia de apnea (Tabla 3).

El modelo tiene un área bajo la curva de 0,74 con p<0,001 con un intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC 95%) de 0,62-0,86.

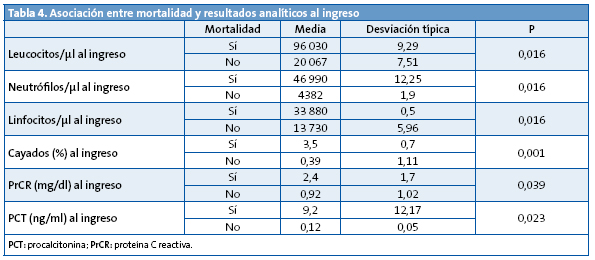

Se objetiva relación entre la mortalidad y el número de leucocitos, neutrófilos y linfocitos; porcentaje de cayados; PrCR y PCT en sangre al ingreso (Tabla 4).

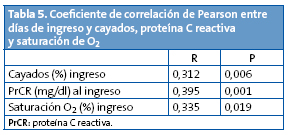

Igualmente, aparece relación entre la duración del ingreso en días con el porcentaje de cayados al ingreso, PrCR al ingreso y saturación de oxígeno al ingreso (Tabla 5).

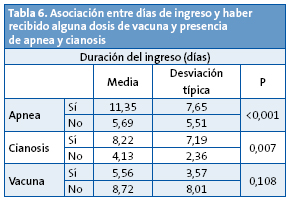

También se establece asociación entre la duración del ingreso en días con la presencia de apnea y cianosis (Tabla 6).

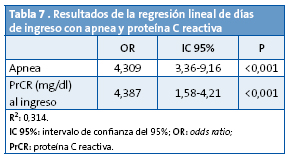

En la regresión lineal continúa como significativo la presencia de apnea y los niveles de PrCR al ingreso (Tabla 7).

DISCUSIÓN Y CONCLUSIONES

La tos ferina es todavía un problema sanitario importante y su hospitalización afecta sobre todo a un grupo de población, los lactantes en los primeros seis meses de vida, con una alta tasa de morbilidad y una no insignificante letalidad9.

La incidencia de tos ferina ha disminuido drásticamente en los países industrializados gracias a la introducción de la vacunación antipertussis a mediados del siglo pasado. Sin embargo, en los últimos años se ha detectado un incremento, especialmente en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes, en Canadá, EE. UU., Australia y algunos países de la Unión Europea10,11.

En el año 2007, la incidencia de tos ferina en la Comunidad de Madrid fue de 2,78 casos por 100 000 habitantes, cifra superior en relación con los dos años anteriores. Este incremento concuerda con el patrón cíclico típico de esta enfermedad. En el año 2008, la incidencia fue de 1,53 casos por 100 000 habitantes. La incidencia de tos ferina ha experimentado un aumento sostenido en los últimos años12-14. Desde el año 2000 se registran incidencias cercanas a 1,5 casos por 100 000 habitantes, con un patrón cíclico característico cada 3-4 años15.

Actualmente, el calendario de vacunación infantil recomienda la administración de cinco dosis de la vacuna DTP acelular (DTPa), a los 2, 4, 6 y 18 meses y a los 4 años, y una dosis de Tdpa a los 14 años de edad. Sin embargo, la dosis de los cuatro años no comenzó a administrarse hasta 1999 y la dosis de los 14 años comenzó a administrarse en 2011. Todo ello implica que el nivel de inmunidad de la población infantil y adolescente podría ser deficiente. La cobertura nacional con la serie primaria supera el 95% desde 199916,17. En 2008, la cobertura nacional con la serie básica (tres primeras dosis) fue del 96,9%, con la primera dosis de refuerzo fue del 94,9%, y con la segunda dosis de refuerzo del 92,3%. El porcentaje de cobertura de vacunación a nivel nacional de la serie básica de DTPa fue del 95,9% en el año 2009, con una clara tendencia a la baja desde el año 2002. El porcentaje de cobertura de vacunación de la serie básica de DTPa en la Comunidad de Madrid fue del 88,6% en el año 2009, también con una clara tendencia a la baja desde años anteriores10,18.

El porcentaje de casos que no han recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna en nuestro trabajo es igual al encontrado en otros estudios realizados en hospitales españoles, pero claramente inferior comparado con los porcentajes de estudios realizados en otros países9,19,20.

La tasa de ingresos debidos a tos ferina en nuestro hospital ha aumentado progresivamente desde el año 2008.

En la mayoría de las series publicadas se describe un predominio del sexo femenino, hecho corroborado en nuestro trabajo21,22. Sin embargo, en otros estudios no se encuentra este claro predominio9,20.

La media de días de ingreso es ligeramente inferior a la aportada por otros estudios de características parecidas9,19.

En el 44,6% de los casos, existía la presencia de un familiar adulto con síntomas compatibles con tos ferina como posible fuente de contagio de la enfermedad, dato que es algo inferior en comparación con el porcentaje aportado por otros estudios. Identificar a un familiar con tos prolongada es importante, porque ayuda a establecer el diagnóstico de tos ferina en el niño y la posibilidad de comenzar de manera precoz el tratamiento para el niño y el resto de familiares con riesgo de contagio23.

En cuanto a los síntomas, en nuestro trabajo se han encontrado porcentajes superiores respecto a otros estudios en la presencia de cianosis y pausas de apnea9,19. Al igual que en el resto de estudios, los síntomas más frecuentes son la tos paroxística, el gallo inspiratorio y el vómito postusígeno9,19,20.

La tasa de complicaciones es mayor a la observada en otros estudios similares, pero el porcentaje de casos que precisan ingreso en la UCI es parecido9.

La aparición de complicaciones durante la evolución de la enfermedad es independiente de la edad del paciente (dato contrario a lo expresado por otros grupos de trabajo), dependiendo esta de otros datos clínicos y analíticos9,19,20.

Los pacientes con complicaciones presentan un mayor porcentaje de cayados en la fórmula leucocitaria y un mayor nivel de PCT en sangre en el momento del ingreso que se relacionan con la presencia de infección bacteriana. También presentan una menor saturación de oxígeno en el momento del ingreso y necesitan oxigenoterapia para su recuperación, dato que se puede deber a que la mayoría de las complicaciones que presentan estos pacientes son respiratorias. Estos datos podrían considerarse predictores de la aparición de complicaciones durante el transcurso de la enfermedad, por lo que estaría indicada la realización de una analítica de sangre y la monitorización con pulsioximetría en una primera atención en niños con sospecha de tos ferina. En este grupo de pacientes existe una menor cobertura vacunal por DTPa, aunque esto puede deberse a que algunos de los niños todavía no han cumplido la edad para la vacunación. Debido a esto, los niños menores de dos meses, que todavía no han recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna, presentan un mayor riesgo de complicaciones. También presentan un mayor porcentaje de síntomas catarrales, pausas de apnea y tos cianosante en el comienzo del cuadro, datos que siguen reforzando que la mayor parte de las complicaciones se deben a problemas respiratorios. Cuando aparezcan estos síntomas acompañando o no al típico cuadro clínico al comienzo de la enfermedad, deberemos estar alerta sobre el posible desarrollo de alguna complicación en la evolución de la enfermedad. Así mismo, se observa una mayor tasa de coinfección por virus respiratorios como el VRS o el adenovirus y, por lo tanto, se aconseja ante la aparición de complicaciones, sobre todo en el ámbito respiratorio, la realización de un test rápido para virus respiratorios en aspirado nasofaríngeo. Respecto a la tasa de coinfección por virus respiratorios, los datos que aparecen en otros estudios son muy dispares, siendo en algunos superiores3 a la cifra encontrada en nuestro trabajo, y en otros, inferiores9,19.

En los últimos años, la letalidad ha disminuido hasta la cifra encontrada en nuestro trabajo, que es similar a la descrita en estudios anteriores9,20.

Los dos únicos pacientes que terminan falleciendo presentan analíticas con mayor número de leucocitos, neutrófilos, linfocitos, porcentaje de cayados y un mayor nivel de PrCR y PCT en sangre. Estas variables se pueden considerar factores de riesgo de peor pronóstico y gravedad de la enfermedad con mayor riesgo de muerte. Otra razón que hace necesaria la analítica de sangre en un primer momento ante la sospecha de tos ferina en un niño. Estos resultados hay que asumirlos con cautela dado el reducido número de pacientes que fallecen.

Los pacientes que presentan apnea y cianosis en algún momento de la evolución de la enfermedad, así como los que no habían recibido vacunación con ninguna dosis de DTPa, precisan ingresos de mayor duración, ya que también está relacionado con una mayor tasa de complicaciones y por lo tanto necesitan más tiempo para la mejoría de su estado de salud.

Se observa una relación lineal entre el nivel de PrCR en la analítica de sangre realizada en el momento del ingreso y los días necesarios de ingreso hospitalario, por lo que se puede considerar este dato analítico como predictor de la duración del ingreso.

En conclusión, el mayor porcentaje de cayados y nivel de PCT, así como la menor saturación de oxígeno, en el momento del ingreso; no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna DTPa; la presencia de síntomas catarrales, apnea y cianosis en el comienzo del cuadro y la coinfección por virus respiratorios se pueden considerar factores de riesgo de la aparición de complicaciones durante el ingreso hospitalario de pacientes con tos ferina.

La presencia de apnea y cianosis al comienzo del cuadro clínico, así como no haber recibido ninguna dosis de vacuna DTPa y mayores niveles de PrCR en el momento del ingreso pueden considerarse factores de riesgo de ingreso hospitalario de mayor duración en pacientes con tos ferina.

La tasa de ingresos debidos a tos ferina ha aumentado progresivamente en nuestro centro en el periodo de tiempo estudiado, mientras que existe una tendencia a la baja en la cobertura vacunal con DTPa, lo que es preocupante y marca la necesidad de mejorar la cobertura vacunal de la población.

CONFLICTO DE INTERESES

Los autores declaran no presentar conflictos de intereses en relación con la preparación y publicación de este artículo.

ABREVIATURAS: CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention • CMBD: conjunto mínimo básico de datos • DTP: vacuna frente a difteria, tétanos y tos ferina • DTPa: vacuna frente a difteria, tétanos y tos ferina acelular • IC 95%: intervalo de confianza del 95% • OR: odds ratio • PCR: reacción en cadena de la polimerasa • PCT: procalcitonina • PrCR: proteína C reactiva • Tdpa: vacuna combinada: antitetánica y con carga antigénica reducida frente a difteria y tos ferina acelular • VRS: virus respiratorio sincitial • UCI: Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- Tan T, Trindade E, Skowronski D. Epidemiology of pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(5 Suppl):S10-8.

- Cherry JD, Grimprel E, Guiso N, Heininger U, Mertsola J. Defining pertussis epidemiology: clinical, microbiologic and serologic perspectives. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(5 Suppl):S25-34.

- Martín Jiménez L, Francis Centeno M, de José Gómez MI. Tos ferina. En: Guerrero Fernández J, Ruiz Domínguez JA, Menéndez Suso JJ, Bariios Tascçon A (eds.). Manual de Diagnóstico y Terapéutica en Pediatría, 5.ª ed. Madrid: Publimed; 2009. p. 779-83.

- Namachivayam P, Shimizu K, Butt W. Pertussis: severe clinical presentation in pediatric intensive care and its relation to outcome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(3):207-11.

- Centers for Disease Control. Pertussis (Whooping Cough). Diagnosis Confirmation [en línea] [actualizado el 24/02/2011] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en www.cdc.gov/pertussis/clinical/diagnostic-testing/diagnosis-confirmation.html

- Beltrán Silva S, Cervantes Apolinar Y, Cherry JD, Conde González C. Consensus on the clinical and microbiologic diagnosis of Bordetella pertussis, and infection prevention. Expert Group on Pertussis Vaccination. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(1):57-65.

- Villuendas MC, López AI, Moles B, Revillo MJ. Bordetella spp. infection: a 19-year experience in diagnosis by culture. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2004;22:212-6.

- Palmer CM, McCall B, Jarvinen K, Nissen MD. Bordetella pertussis PCR positivity, following onset of illness in children under 5 years of age. Commun Dis Intell. 2007;31:202-5.

- Ferrer Marcellés A, Moraga Llop FA, Olsina Tebar M, Campins Martí M, Planells Romeu I. Tos ferina confirmada por cultivo en un hospital terciario en un perioro de 12 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2003;58:309-15.

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Sección de enfermedades transmisibles. Dirección General de Atención Primaria. Servicio Madrileño de Salud. Informe Tos Ferina, año 2007 [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en http://bit.ly/KUYzbO

- Bettinger JA, Halperin SA, De Serres G, Scheifele DW, Tam T. The effect of changing from whole-cell to acellular pertussis vaccine on the epidemiology of hospitalized children with pertussis in Canada. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:31-5.Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de España. Informe anual. Año 2008 [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en http://bit.ly/KUYhBO

- Bhatt P, Halasa N. Increasing rates of infants hospitalized with pertussis. Tenn Med. 2007;100(5):37-9, 42.

- Fung KS, Yeung WL, Wong TW, So KW, Cheng AF. Pertussis a re-emerging infection? J Infect. 2004;48:145-8.

- Cardeñosa N, Romero M, Quesada M, Oviedo M, Carmona G, Codina G, et al. Is the vaccination coverage established enough to control pertussis, or it is a re-emerging disease? Vaccine. 2009;27:3489-91.

- Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de España. Informe anual. Año 2008 [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en http://bit.ly/KUYhBO

- Therre H, Baron S. Pertussis immunisation in Europe: the situation in late 1999. Euro Surveill. 2000;5(1):6-10.

- Olin P, Hallander HO. Marked decline in pertussis followed reintroduction of pertussis vaccination in Sweden. Euro Surveill. 1999;4:128-9.

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad. Coberturas de vacunación, datos estadísticos [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en www.msps.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/coberturas.htm

- Horcajada Herrera I, Hernández Febles M, González Jorge R, Colino Gil E, Bordes Benítez A, Pena López MJ. Estudio clínico-epidemiológico de la infección por Bordetella pertussis en la isla de Gran Canaria en el periodo 2003-2007. An Pediatr (Barc). 2008;69:200-4.

- Elliott E, McIntyre P, Ridley G, Morris A, Massie J, McEniery J, et al. National study of infants hospitalized with pertussis in the acellular vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:246-52.

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Boletín Epidemiológico de la Comunidad de Madrid. N.º 1-12. Volumen 16. Enero-diciembre 2010 [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en http://bit.ly/KUY95a

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Boletín Epidemiológico de la Comunidad de Madrid. Nº 1. Volumen 17. Enero 2011 [en línea] [consultado el 14/05/2012]. Disponible en http://bit.ly/KUY55w

- Munoz FM. Pertussis in infants, children, and adolescents: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2006;17:14-9.