Vol. 28 - Num. 109

Original Papers

Implementation of a pilot screening program for Chagas disease in the pediatric population of Guadalajara, Spain

Marta Belén Roldán Rodrígueza, Alejandro González Praetoriusb, Ramón Pérez Tanoirac, Mario Pérez Butragueñod, Alfonso Ortigado Matamalae

aAlumna de Escuela Doctorado. Universidad de Alcalá de Henares. Alcalá de Henares. Madrid. Pediatra rede CUF Lisboa. Portugal. Pediatra SESCAM. Guadalajara. España.

bServicio de Microbiología. Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara. Guadalajara. España.

cServicio de Microbiología. Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias. Alcalá de Henares. Madrid. España.

dServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor. Madrid. España.

eServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara. Guadalajara. España.

Reference of this article: Roldán Rodríguez MB, González Praetorius A, Pérez Tanoira R, Pérez Butragueño M, Ortigado Matamala A. Implementation of a pilot screening program for Chagas disease in the pediatric population of Guadalajara, Spain . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2026;28:[en prensa].

Published in Internet: 09-02-2026 - Visits: 396

Abstract

Introduction: Chagas disease (ChD), endemic in 21 Latin American countries, has spread globally due to migratory movements. Spain is the European country with the highest number of cases, where vertical transmission is the main mechanism of infection. In 2024, the Spanish Ministry of Health developed a prenatal screening protocol for ChD; however, there is no unified pediatric protocol currently in place. Early diagnosis and treatment in childhood could reduce morbidity and mortality and prevent new cases of vertical transmission.

Objective: to evaluate the implementation and results of a pilot Chagas disease screening program in the pediatric population of the province of Guadalajara, Spain.

Material and methods: we carried out a prospective study (October 2022–December 2024) in primary care centers in the province of Guadalajara. A structured questionnaire was used to assess epidemiological characteristics and knowledge of the disease, and serological screening (ELISA/CLIA) was offered to children from endemic countries. We analyzed knowledge level, coverage, adherence, and perceived barriers.

Results: a total of 588 children participated (47% of the target population), of whom 325 (55.3%) underwent serological testing. No positive cases were detected. Having seen the vector was significantly associated with knowing about the disease, but no variables were associated with screening adherence.

Conclusions: pediatric screening for Chagas disease is feasible and enables early diagnosis. Identifying and addressing the barriers that limit participation in screening is essential to improve adherence and optimize detection and treatment in at-risk children.

Keywords

● Chagas disease ● Health knowledge, attitudes, practice ● Mass screeningINTRODUCTION

Chagas Disease (ChD) is endemic in 21 countries in Latin America. Due to migration movements and international travel, its distribution has spread worldwide.1,2 Spain is the country with the highest number of reported cases in Europe and the second non-endemic country in the world with the highest number of cases, with an estimated 50 000 to 75 000 infected individuals and substantial underdiagnosis.3-5

In Spain, the main mechanism of transmission is vertical transmission.6,7 Although a nationwide prenatal screening protocol for women from endemic countries was introduced in 2024,8 there is no standardized protocol for the pediatric population. Given the typically silent course of the disease, early diagnosis and treatment during childhood can contribute to reducing long-term complications and the risk of vertical transmission once individuals reach reproductive age.1,9

The efficacy of etiological treatment increases when the disease is diagnosed in the early stages and decreases as the disease advances. Contrary to adults, the response rate in children is high, even in chronic phases of disease, in addition to a lower frequency of adverse events.10,11 There is evidence suggesting that the cure rate can be very high if infants infected during gestation or birth receive early treatment in the first year of life.12 If the disease is diagnosed in the advanced stages, when there is already cardiac involvement, etiological treatment does not reverse the structural damage nor reduces the incidence of major cardiovascular events, as described in cohorts of patients with chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy.13,14

The primary objective of our study was to assess the implementation and outcomes of a pilot ChD screening program in the pediatric population from endemic countries. The secondary objectives included estimating the current prevalence, identifying barriers to participation in the program and analyzing the sociodemographic, epidemiological and knowledge-related factors associated with undergoing screening.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a prospective study between October 2022 and December 2024 in primary care centers in the province of Guadalajara, Spain.

Since reliable data on the pediatric prevalence of ChD in Spain were not available, we were unable to conduct a classic sample size calculation based on the expected proportion. However, given an estimated target of 1499 children, we estimated that a sample of 325 children would allow estimating proportions with an approximate precision of ±5% with a 95% level of confidence.

Study sample and setting

All pediatricians and family physicians with pediatric caseloads in primary care centers and local clinics in the province were invited to participate. In the end, 24 providers participated (21 in primary care and 3 hospital-based), whose caseloads accounted for 47% of the minors from endemic countries currently residing in Guadalajara.

We included all children aged less than 14 years who resided in the geographical area covered by the study, born in endemic countries based on data from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)9 assigned to the caseloads of participating providers.

The countries endemic for Chagas disease were identified according to the reports of the PAHO, which considers the disease endemic in 21 countries of Latin America. The specific group of countries included in this study was based on the Consensus document for the detection and management of Chagas disease in Primary Health Care published in 2015.9,15

We excluded children that had undergone screening for ChD previously after their last stay in the country, as well as cases in which the parents or legal guardians refused to participate, the questionnaire was not completed or the family could not be reached in any of three documented attempts.

Study protocol

The Information and Communication Technology team of the Department of Health of Castilla-La Mancha provided the lists of names of children born in endemic countries registered in the provincial public health system. Based on these lists, we reviewed the electronic health records of the children to determine whether they had previously undergone screening for ChD.

Subsequently, interviews were conducted with the parents or legal guardians, by telephone or in person, to collect data on basic epidemiological variables and determine their baseline knowledge about (Figure 1). All of them were provided with verbal and written information about the objectives of the study and about the disease, along with a specific informed consent form.

In addition, families were offered free screening for ChD, to be conducted in their local primary care center. Screening was performed by chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) with the Chagas VirClia® IgG + IgM Monotest (Vircell, Spain). When the result was positive or indeterminate, the samples were submitted to the National Microbiology Center to conduct a second test with a diagnostic serologic technique (in-house enzyme-linked immunoassay [ELISA]). If both tests were positive, the diagnosis was confirmed; in the case of disagreement, a third test was performed with another diagnostic technique (in-house indirect immunofluorescence [IIF]).

Variables

We collected data on sociodemographic variables (date and country of birth), epidemiologic variables (duration of residence in endemic country and type of setting [rural, urban or mixed]), variables related to the knowledge and history of ChD (previous knowledge, having seen the vector of disease [kissing bugs], and having relatives or acquaintances with a diagnosis of ChD) and screening-related variables (performance and results of serologic test, year of screening and diagnostic confirmation). Age was calculated in full years taking 31 December 2023 as reference.

Sociodemographic data were retrieved from the electronic health records, epidemiological and knowledge-related data through a structured interview with the parents, and the results of screening from the records of the reference laboratory.

We used these data for the following purposes:

- Assess the representativeness of the sample in relation to the pediatric population born in endemic countries residing in the province.

- Assess the association of sociodemographic or epidemiological characteristics with knowledge of the disease and adherence to screening.

- Estimate the observed prevalence of ChD in the screened population.

Statistical analysis

We compared the characteristics of children in the sample to the total population of children born in endemic countries that resided in the province (sex, age, setting and country of origin) to assess the representativeness of the recruited sample. In addition, we compared the characteristics of the subgroup of children that completed serologic testing in the sample vs the subgroup that did not to identify potential sources of participation bias.

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables as median and interquartile range (IQR), as applicable for their distribution. We calculated the 95% confidence intervals (95 CIs) using the Wilson score interval method for general proportions and the exact Clopper-Pearson (binomial) method for low-frequency proportions.

Bivariate associations were assessed by means of the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as applicable. We fitted multivariate logistic regression models: one for the variables associated with the knowledge of ChD and another in relation to the adherence to screening. The results were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95 CIs, and we considered p values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Research with Medicines of the Hospital de Guadalajara (CEIM code, 2022.PR.40) and adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

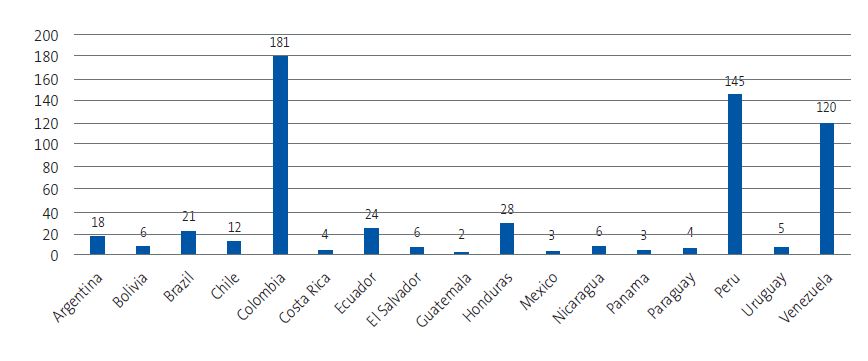

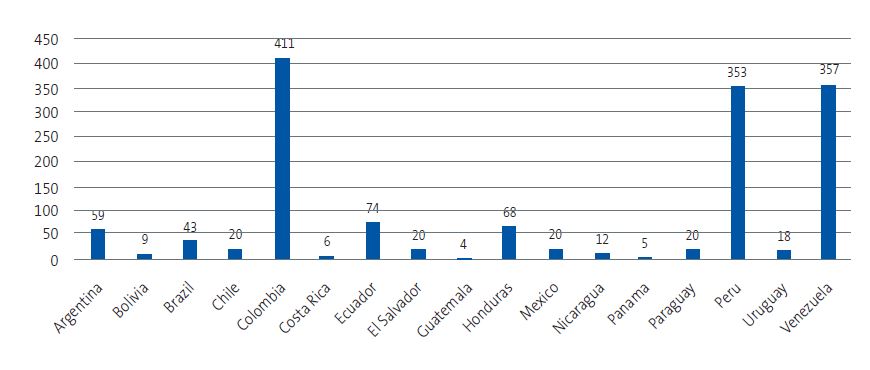

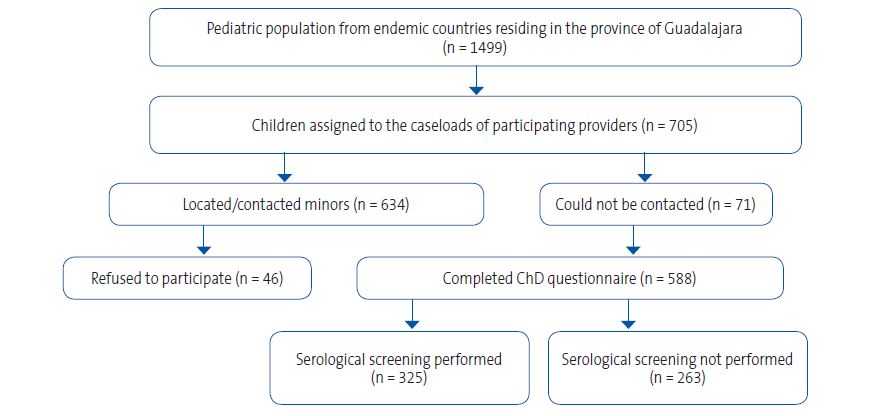

A total of 1499 children aged 0 to 14 years from 17 of the 21 countries endemic for ChD resided in Guadalajara. Of this total, 705 were assigned to the caseloads of the participating providers (Figures 2 and 3). A total of 634 children could be reached and, after 46 families refused participation, 588 completed the questionnaire about ChD. Finally, 325 children underwent screening with a serological assay. Figure 4 summarizes the study protocol. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the population in the province, the surveyed children and the children who underwent screening.

| Figure 2. Distribution of participating children by country of birth |

|---|

|

| Figure 3. Distribution by country of origin of children from endemic areas residing in the province of Guadalajara |

|---|

|

| Figure 4. Flow chart of study participation. The chart shows the process of identifying and contacting candidates, agreement to participation, and performance of serological screening in the pediatric population from endemic countries residing in the province of Guadalajara |

|---|

|

| Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the pediatric population from endemic countries. Data are expressed as n (%) or median (interquartile range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Population in province (n = 1499) | Respondents (n = 588) | Screened (n = 325) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 795 (53.0) | 320 (54.4) | 171 (52.6) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 704 (47.0) | 268 (45.6) | 154 (47.4) |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 9 (7-12) | 9 (7-11) | 9 (7-11) |

| Source: table developed from the data obtained in our study. | |||

Knowledge of the disease

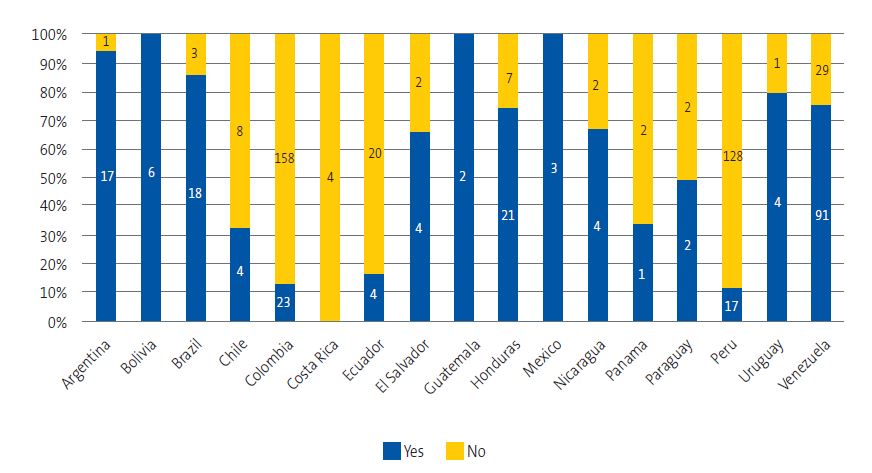

Of the total survey respondents, 221 (37.6%) reported knowing ChD, while 367 (62.4%) did not know what it was. The degree of knowledge varied considerably between countries, with percentages exceeding 90% among respondents from Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico, Guatemala and Venezuela, and below 20% among respondents from Colombia, Ecuador and Peru (Figure 5). The chi-square test showed a statistically significant association between country of origin and knowledge of ChD (χ2 = 262.88; p < 0.001).

| Figure 5. Knowledge of Chagas disease by country of origin |

|---|

|

As regards the residential setting in the country of origin, 115 children (19.6%) had lived in rural settings, 457 (77.7%) in urban settings and 16 (2.7%) in both. The percentage that knew ChD was 36.5% in the rural group, 37.2% in the urban group and 60% in the group that had lived in both settings, without statistically significant differences (χ2 = 2.43; p = 0.297).

Exposure and family history

A total of 176 children (29.9%) reported seeing kissing bugs in their countries of origin. The proportion was significantly greater among children who had been living in rural settings (38.3%) compared to urban (27.3%) or mixed (46.7%) settings (χ2 = 6.71; p = 0.035). Having seen the bugs was associated with the proportion that knew about the disease: 50% of children who had seen the vector knew about ChD compared to 32.3% of those who had not seen it (χ2 = 15.76; p < 0.001; OR = 2.10; 95 CI: 1.46-3.01).

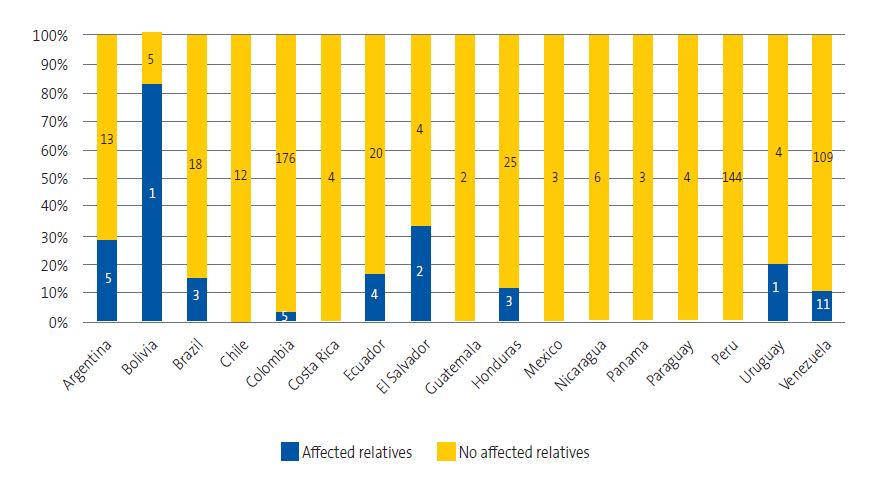

Forty children (6.8%) reported having relatives or acquaintances with a diagnosis of ChD, which corresponded to 10.4% of children from rural settings, 5.5% from urban settings and 18.7% from mixed settings (χ2 = 7.27; p = 0.026). The frequency of having relatives or acquaintances affected by the disease varied significantly based on the country of origin (χ2 = 98.93; p < 0.001) (Figure 6).

| Figure 6. Children with affected relatives by country of origin |

|---|

|

The multivariate model showed that having seen the bugs was the only factor independently associated with knowing the disease (OR = 2.17; 95 CI: 1.51-3.14; p < 0.001).

Adherence to screening

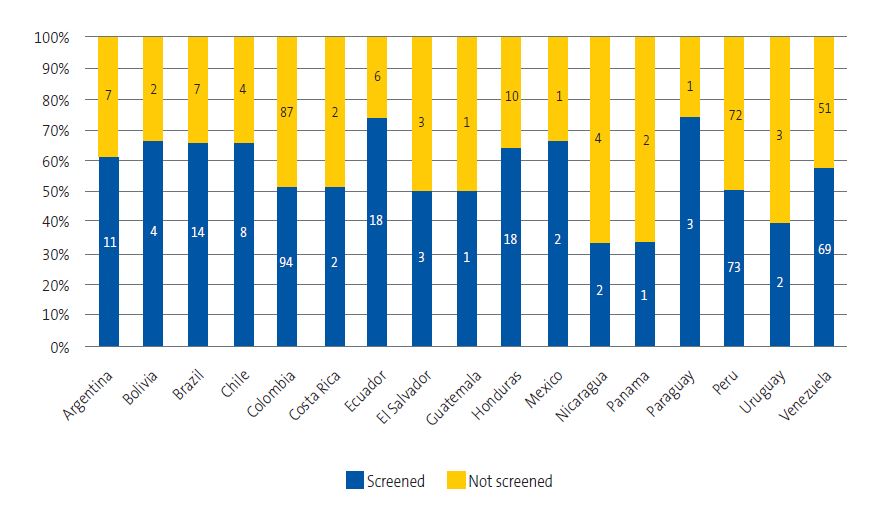

Of the 588 children with completed questionnaires, 325 underwent screening. The screening program coverage amounted to 46.1% of the children assigned to the caseloads of participating providers and 55.3% of children with completed questionnaires. The participants came from 17 endemic countries, with a screening coverage that ranged between 50% and 62%, without significant differences between countries of origin (χ2 = 13.56; p = 0.757) (Figure 7).

| Figure 7. Percentage of participating children that did and did not undergo screening by country of origin |

|---|

|

Of the 221 children who reported knowing the disease, 58.4% underwent screening, compared to 53.4% of children who did not know about it (χ2 = 1.35; p = 0.245). We also found no significant differences in the adherence to screening based on the residential setting (rural 53%; urban 56%; mixed 50%; χ2 = 0.51; p = 0.774).

Of the 176 children that had seen kissing bugs, 55.1% underwent screening, compared to 55.3% of those who had not seen them (χ2 = 0.00; p = 1.000). Having relatives or acquaintances affected by the disease also was not associated with increased adherence (57.5% versus 55.5%; χ2 = 0.02; p = 0.897).

In the adjusted model, none of the analyzed variables exhibited a statistically significant association with adherence to screening:

- Knowing the disease (OR = 1.26; 95 CI: 0.87-1.80; p = 0.218).

- Having seen the bugs (OR = 0.97; 95 CI: 0.67-1.40; p = 0.851).

- History of ChD in relatives or acquaintances (OR = 0.99; 95 CI: 0.49-2.00; p = 0.969).

- Urban vs. rural setting (OR = 1.32; 95 CI: 0.48-3.60; p = 0.588).

- Mixed vs. rural setting (OR = 1.18; 95 CI: 0.41-3.37; p = 0.759).

Results of screening

No positives cases were identified in any of the 325 screened children, which corresponds to an observed prevalence of 0.0% (95 CI: 0.0-0.92; Clopper-Pearson binomial exact method).

DISCUSSION

In this study, following the recommendations of the Program for the Care of Immigrant Children of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Pediatrics)15,16 and the World Health Organization,17 we implemented a pilot Chagas disease screening program in the pediatric population from endemic countries within a health care system in which there is no standardized pediatric screening program. Screening of children and adolescents is particularly relevant, as early diagnosis and treatment are associated with improved clinical outcomes at this stage and can prevent long-term complications.

Although all pediatricians and family physicians with pediatric caseloads in the province were invited to participate, only approximately half of those with patients potentially eligible for screening agreed to participate. The low participation affected the sample size and the achieved screening coverage, and probably reflected the excessive provider workloads, the low visibility of ChD in clinical practice and the limited awareness of its clinical relevance among health care professionals.

Of the families that could be contacted, 83.4% chose to participate, but only 55.3% of children underwent the serology test for screening, which evinces difficulties in the recruitment and retention of the target population, even when pediatric care is accessible and free. Some of the probable causes are the lack of knowledge about the disease, fear of stigmatization,18 the absence of clinically recognizable symptoms in the initial stages and logistical barriers, such as schedule incompatibilities or the refusal of blood draws. Similar situations have been described in other studies in the migrant population in Spain, in which less than half of the children of affected mothers underwent screening.19

Among those surveyed, 62.4% did not know about ChD, which was consistent with what has been reported in other non-endemic contexts, where the low level of knowledge about the disease constitutes a significant barrier to appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Although we found differences according to the country of origin, we did not find a clear correlation between the level of knowledge and the prevalence of the disease, in agreement with previous studies that suggested that risk perception does not always reflect the actual epidemiological burden.20,21

The factor most strongly associated with knowledge of ChD was having seen the vector (OR = 2.10; 95 CI: 1.46-3.01), although only half of those who reported seeing the bugs stated that they knew the disease. This finding suggests a disconnect between exposure and perceived risk, as described in other contexts.22,23 We also found no differences in knowledge based on geographical setting (urban or rural setting), reflecting a somewhat homogeneous lack of health information in different groups of immigrants.

As regards adherence, none of the analyzed factors—country of origin, knowledge of the disease, geographical setting, exposure to the vector or family history—was significantly associated with undergoing screening. These results show that knowledge of the disease does not guarantee participation in the screening program and that other structural and cultural barriers are at play. Several authors have proposed strategies integrating screening in community-based activities, offering flexible screening hours and reinforcing communication via cultural mediators and health promotion professionals.24

Another strategy that could improve adherence would be the use of rapid tests in the pediatrician’s office for initial screening. Although their sensitivity is slightly lower compared to conventional serology tests, the PAHO supports its use in areas with limited access to complex testing facilities or where adherence is low, always in the framework of diagnostic protocols that include serological confirmation.25 Recent studies show that “duo” rapid testing strategies with the simultaneous use of two rapid techniques offer a high sensitivity and specificity that approach those of conventional serological assays and can facilitate timely diagnosis.26-28

Performing screening at the time of an office visit precludes the need to make additional visits to a laboratory and other logistic barriers, such as school and work schedules. However, the potential implementation of rapid testing in pediatric practice would first require specific assessments of the feasibility, cost-effectiveness and appropriateness of the approach in the local health care context.

In our cohort, screening did not turn out positive in any case (observed prevalence = 0.0%; 95 CI: 0.0-0.92), which was consistent with the low endemicity in the predominant countries of origin. However, the low coverage of screening precluded estimation of the population prevalence or ruling out undiagnosed infections. Several cost-effectiveness studies have even demonstrated that systematic screening for ChD is still cost-effective with prevalences below 0.05%.29 Thus, our findings cannot be applied to modify the current recommendation of systematic screening of children from endemic countries, but they do evince the need for strategies to improve recruitment and adherence.

There are limitations to this study that should be taken into consideration when interpreting its results:

First of all, although we collected data on how long families resided in the country of origin, we did not obtain detailed information on subsequent recurrent trips or prolonged stays following migration, which may have led to an incomplete approach to the classification of the risk of infection through Trypanosoma cruzi. Furthermore, the low adherence to screening may have affected the estimates obtained in the analysis.

It is also important to remember that participation was voluntary and not randomized, which may also limit the representativeness of the sample and the external validity of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study evinces the current challenges in pediatric screening for Chagas disease in non-endemic areas, with a low screening coverage and a low level of knowledge of this disease among families, factors that, combined with the absence of a unified protocol, hinder its adequate implementation.

The implementation of a Trypanosoma cruzi screening program in the pediatric population from endemic countries proved feasible in our province, although adherence was poor. The absence of detected cases, combined with the low participation, suggests potential underdiagnosis in this age group.

Reinforcing the training of health care professionals, adapting communication to the sociocultural context and addressing existing structural barriers are key to improve recruitment and the effectiveness of the program. In this regard, pediatric screening should be established as a pillar that complements prenatal screening to establish a solid foundation for early diagnosis, curative treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission of Chagas disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare having no conflicts of interest in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the development of the published manuscript.

This study was presented as an oral communication at the 39th National Congress of the Sociedad Española de Pediatría Extrahospitalaria y Atención Primaria (SEPEAP) and the IV Congreso Hispano-Luso de Pediatría (Spanish-Portuguese Pediatrics Congress) held in Seville in October 2025.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted in the framework of the doctoral dissertation of Marta Belén Roldán Rodríguez (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares) and the CHAGUAPED Group research project.

The authors thank the health care professionals who participated in the study and the Department of Microbiology of Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara.

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT during editing for the sole purpose of improving the style and composition of the manuscript, which had no bearing on the scientific content of the manuscript or the interpretation of results.

ABBREVIATIONS

CI: confidence interval · ChD: Chagas disease · CLIA: chemiluminescence immunoassay· ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay · IIF: indirect immunofluorescence · OR: odds ratio.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). In: WHO [online] [accessed 03/02/2026]. Available at www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/chagas-disease

- Lidani KCF, Andrade FA, Bavia l, Damasceno FS, Beltrame MH, Messias-Reason IJ, et al. Chagas disease: From discovery to a worldwide health problem. Frontiers Public Health. 2019;7:166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00166

- Navarro M, Reguero l, Subirà C, Blázquez-Pérez A, Requena-Méndez A. Estimating chagas disease prevalence and number of underdiagnosed and undertreated individuals in Spain. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;47:102284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102284

- Grupo de Chagas de la CAM. Sociedad Madrileña de Microbiología Clínica. Chagas [online] [accessed 03/02/2026]. Available at www.smmc.es/chagas

- Molina I, Salvador F, Sánchez-Montalvá A. Actualización en enfermedad de Chagas. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2016;34(2):132-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2015.12.008

- Colombo V, Giacomelli A, Casazza G, Galimberti l, Bonazzetti C, Sabaini F, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in Latin American pregnant women living outside endemic countries and frequency of congenital transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Travel Med. 2021;28(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa170

- González Sanz M, Crespillo Andújar C, Chamorro Tojeiro S, Monge Maillo B, Pérez Molina JA, Norman FF. Chagas Disease in Europe. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023;8. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8120513

- Grupo de trabajo de cribado prenatal de enfermedades infecciosas de la Ponencia de cribado poblacional. Protocolo de consenso para el cribado prenatal de la enfermedad de Chagas. Madrid. Ministerio de Sanidad, 2024 [online] [accessed 03/02/2026]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/cribado/cribadoPrenatal/enfermedadesInfecciosas/docs/Documentoconsensocribadoprenatal_enfermedadChagas.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization. Síntesis de evidencia: Guía para el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la enfermedad de Chagas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e28. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.28

- Moscatelli G, Moroni S, Bournissen FG, González N, Ballering G, Schijman A, et al. Longitudinal follow up of serological response in children treated for Chagas disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(8):e0007668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007668

- González NL, Moscatelli G, Moroni S, Ballering G, Jurado l, Falk N, et al. Long-term cardiology outcomes in children after early treatment for Chagas disease, an observational study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010968

- Edwards MS, Stimpert KK, Bialek SR, Montgomery SP. Evaluation and management of congenital chagas disease in the United States. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8(5):461-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piz018

- Pecoul B, Batista C, Stobbaerts E, Ribeiro I, Vilasanjuan R, Gascon J, et al. The BENEFIT Trial: Where Do We Go from Here? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004343

- Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A, Sosa-Estani S, Rassi A, Rosas F, et al. Randomized trial of benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):295-306. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507574

- Roca Saumell C, Soriano Arandes A, Solsona Díaz l, Gascón Brustenga J, Grupo de consenso Chagas-APS. Revista de Pediatría de Atención Primaria - Documento de consenso sobre el abordaje de la enfermedad de Chagas en Atención Primaria de salud de áreas no endémicas. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015;17:e1-e12.

- Ma Masvidal Aliberch R, Canadell Villaret D. Guía de Algoritmos en Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Algoritmos AEPap. Atención al niño y la niña inmigrantes [online] [accessed 03/02/2026]. Available at https://algoritmos.aepap.org/algoritmo/68/atencion-al-nino-y-la-nina-inmigrantes

- World Health Organization - Chagas Disease. In: WHO [online] [accessed 03/02/2026]. Available at www.who.int/health-topics/chagas-disease

- Ventura-Garcia l, Roura M, Pell C, Posada E, Gascón J, Aldasoro E, et al. Socio-Cultural Aspects of Chagas Disease: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(9):e2410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002410

- Romay-Barja M, Boquete T, Martínez O, González M, Arco DA Del, Benito A, et al. Chagas screening and treatment among Bolivians living in Madrid, Spain: The need for an official protocol. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213577

- Del Carmen Díez Hernández M, Elkheir N, Fisayo T, Gonçalves R, Grover Sañer Liendo E, Bern C, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices toward Chagas Disease: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Bolivians in the Gran Chaco and Latin American Migrants in London. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2025;113(1):25. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.24-0516

- Romay Barja M, Iglesias Rus l, Boquete T, Benito A, Blasco Hernández T. Key Chagas disease missing knowledge among at-risk population in Spain affecting diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00841-4

- Ochoa Díaz MM, Orozco García D, Fernández Vasquez RS, Eyes Escalante M. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Chagas a Neglected Tropical Disease in Rural Communities of the Colombian Caribbean, CHAGCOV Study. Acta Parasitol. 2024;69(2):1148-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11686-024-00833-y

- Mora-Criollo P, Carrasco-Tenezaca M, Casapulla S, Bates BR, Grijalva MJ. A qualitative exploration of knowledge of Chagas disease among adolescents in rural Ecuador. Rural Remote Health. 2023;23(1).

- Ayres J, Marcus R, Standley CJ. The Importance of Screening for Chagas Disease Against the Backdrop of Changing Epidemiology in the USA. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2022;9(4):185-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-022-00264-7

- Pan American Health Organization. Uso de pruebas de diagnóstico rápido para la enfermedad de Chagas en las Américas. Pan American Health Organization, editor. Washington DC: PAHO; 2025. https://doi.org/10.37774/9789275329382

- Pérez F, Vermeij D, Salvatella R, Castellanos LG, de Sousa AS. The use of rapid diagnostic tests for chronic Chagas disease: An expert meeting report. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18(8):e0012340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0012340

- Lozano D, Rojas l, Méndez S, Casellas A, Sanz S, Ortiz l, et al. Use of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for conclusive diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease – field implementation in the Bolivian Chaco region. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(12):e0007877. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007877

- Suescún-Carrero SH, Tadger P, Cuellar CS, Armadans-Gil l, López LXR. Rapid diagnostic tests and ELISA for diagnosing chronic Chagas disease: Systematic revision and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(10):e0010860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010860

- Requena-Méndez A, Bussion S, Aldasoro E, Jackson Y, Angheben A, Moore D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Chagas disease screening in Latin American migrants at primary health-care centers in Europe: a Markov model analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(4):e439-47.