Vol. 26 - Num. 101

Original Papers

Motivational interviewing as a strategy to improve the oral health of children and caregivers. Umbrella review

Ana M.ª Horta Mayaa, Luisa Fernanda Gutiérrez Gutiérreza, Cecilia M.ª Martínez Delgadoa, Daniel Demetrio Faustino Silvab, M.ª del Carmen Villanueva Vilchisc, M.ª de los Ángeles Ramírez Trujillod, Ricardo Cartés Velásqueze

aFacultad de Odontología. Universidad CES Medellín. Colombia.

bHospitalar Conceição. Porto Alegre. Brasil.

cFacultad de Odontología. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores Unidad León. Guanajuato. México.

dEscuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores Unidad León. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México.

eUniversidad de Concepción. Chile.

Correspondence: CM Martínez. E-mail: cmariamar@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Horta Maya AM, Gutiérrez Gutiérrez LF, Martínez Delgado CM, Faustino Silva DD, Villanueva Vilchis MC, Ramírez Trujillo MA, et al. Motivational interviewing as a strategy to improve the oral health of children and caregivers. Umbrella review . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2024;26:e1-e12. https://doi.org/10.60147/2cb1e384

Published in Internet: 21-02-2024 - Visits: 12425

Abstract

Objective: to demonstrate the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in improving oral health indicators in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers.

Material and method: umbrella review design. Search of electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, SCOPUS, EBSCO) and Google Scholar for articles published between 2010 and 2020 using the following search string: ('Motivational interviewing' OR 'motivational interview' OR 'motivational interviewing style' OR 'motivational intervention' OR 'motivational counseling' OR 'brief motivational counseling' OR 'maternal counseling' OR 'behavioral intervention') AND (“caries” OR 'dental caries' OR 'tooth decay' OR 'dental decay' OR 'carious lesions' OR 'DMFT index' OR “ICDAS”) AND ('gingival diseases' OR “gingivitis” OR “CPITN” OR 'gingival bleeding' OR 'dental calculus') AND (“children” OR “families” OR “caregivers”). We selected original articles on the effectiveness of motivational interviewing in oral health (MIOH) in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers that were systematic review or meta-analyses of the scientific literature.

Results: the search yielded 69 articles (2 were systematic reviews and 4 meta-analyses). The indicators found in the review were: change in early childhood caries, oral hygiene, gingival conditions and frequency of visits to the dental clinic, with promising outcomes and some contradictory results.

Conclusion: the evidence on the effectiveness of motivational interviewing compared to conventional health education shows positive changes in oral health indicators such as improvement in dental hygiene and the development of caries in early childhood, among others.

Keywords

● Caregivers ● Dental caries ● Dental Hygiene ● Motivational interviewing ● PreventionINTRODUCTION

There are various health education strategies aimed at changing deleterious habits by healthy habits. One of them, motivational interviewing (MI) was described and applied for the first time by Miller in 1983 in his clinical practice with alcohol abusers and their rehabilitation.1 Rollnick and Miller define it as a “directive, client-centred counselling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence”,2 that is, contradictory feelings about maintaining or changing a habit, a routine or a way of doing or behaving.

In this intervention, the professional must interact with patients in such a way that encourages them to think about a necessary change by increasing their intrinsic motivation to change, 2-5 using a collaborative communication style as opposed to the traditional prescriptive style typically used in health education campaigns.

Thus, IM is characterised by guiding, rather than directing or imposing, applying a specific skillset to generate rapport and promote these changes, so that individuals can assess their own behaviour, identify it and reflect on their ambivalence in order to come to an acceptable solution.

The literature on the application of MI in oral health is scarce; the first study that assessed the effectiveness of MI in oral health outcomes was published in 1996 by Stewart et al.5 In 2013, oral health was included in a systematic review among other health care outcomes.6

In light of the growing number of systematic reviews on IM applied to oral health, we considered synthesising the existing evidence y performing a “review of literature reviews”, commonly referred to as an umbrella review,7 to assess the effectiveness of this approach in improving oral health outcomes in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers and contribute evidence useful for its application in health education.

The research question was: What are the changes achieved with the motivational interviewing strategy in oral health indicators in children and their caregivers?

METHODS

The project for this article was approved by the research ethics committee of the School of Dentistry of the Universidad CES (meeting minute 003 of April 2021).

PICO framework:

P = Children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers.

I = motivational interviewing for oral health.

C = duration of sessions.

O = changes in toothbrushing habits, gum health and dental health.

Inclusion criteria

Articles corresponding to systematic reviews (SRs) and/or meta-analyses (MAs) of the literature regarding the effectiveness of motivational interviewing for oral health (MIOH) in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers, published in the past 10 years (starting in 2010) with no limits regarding the duration of followup of the studies.

Databases and search strategy

We conducted a search in electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, EBSCO) as well as Google Scholar using the following search string: ('Motivational interviewing' OR 'motivational interview' OR 'motivational interviewing style' OR 'motivational intervention' OR 'motivational counseling' OR 'brief motivational counseling' OR 'maternal counseling' OR 'behavioral intervention') AND (“caries” OR 'dental caries' OR 'tooth decay' OR 'dental decay' OR 'carious lesions' OR 'DMFT index' OR “ICDAS”) AND ('gingival diseases' OR “gingivitis” OR “CPITN” OR 'gingival bleeding' OR 'dental calculus') AND (“children” OR “families” OR “caregivers”).

Study selection process

Two reviewers (AMH and LFG) each selected studies based on the titles and abstracts, independently and in duplicate, after which they reviewed the full text of each of the selected articles, first applying, the PRISMA checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)8 and then the AMSTAR-29 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews, second revision). A third researcher (CMMD) revised the identified discrepancies between the 2 reviewers and helped resolve them by consensus.

Data extraction

Two reviewers extracted the data, including the title of the article, author(s), journal and year of publication, country, objective(s) of the study, questions aligned with PICO framework (population, intervention, control group, outcome), number of studies included in review, type of trial, population under study, study variables, primary outcomes.

Risk of bias of reviews (critical evaluation of individual sources of evidence)

The evaluation of the selected articles was based on the PRISMA checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) used to assess the quality of reports, applying an arbitrary scale by which researchers, for each item of the PRIMA checklist, assigned a score 0 if the source did not meet the criterion and of 1 if it met the criterion, adding up to a maximum possible total score of 27 points (if all the criteria on the checklist were met). Scores of 20 to 27 points were considered indicative of low risk of bias, scores of 11 to 19 points of moderate risk of bias and scores of 1 to 10 points of a high risk of bias.

Subsequently, each review was assessed using the AMSTAR-2 instrument,9 which comprises 16 items; for each item, the review received a score of 0 if “the item did not apply or was not reported”, of 1 if the item as “partially met” and of 2 if it was “fully met”. Applying this instrument, researchers determined the number of flaws in critical domains, and attributed a high confidence in the results of the review if it did not have weaknesses or at most one non-critical weakness, a moderate confidence if it had no critical weaknesses but more than one non-critical weakness, a low confidence if it had one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses, and a critically low confidence if it had more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses. The results of this assessment are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

| Table 1. Evaluation of the quality of the studies included in the umbrella review and summary of the risk of bias of the included studies based on the PRISMA checklist | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | PRISMA (score) | Risk of bias | Type of review* | Quality score |

| Cascaes et al., 2014 | 22/27 | Low | SR | Moderate |

| Gayes and Steele, 2014 | 24/27 | Low | SR + MA | Moderate |

| Gao et al., 2014 | 20/27 | Low | SR | Moderate |

| Borreli et al., 2015 | 21/27 | Low | SR + MA | Moderate |

| Colvara et al., 2020 | 26/27 | Low | SR + MA | High |

| Faghihian et al., 2020 | 22/27 | Low | SR + MA | High |

|

SR: systematic review of the literature; SR + MA: systematic review with meta-analysis. |

||||

| Table 2. Critical appraisal of the studies included in the umbrella review using the AMSTAR-2 guideline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMSTAR-2: A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews | |||||||

| Items | Cascaes et al., 2014 | Gayes and Steele, 2014 | Gao et al., 2014 | Borreli et al., 2015 | Colvara et al., 2020 | Faghihian et al., 2020 | |

| 1 | Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO? | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol? | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review? | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail? | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? | N/A | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 12 | If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis? | N/A | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | Did the review authors account for RoB in primary studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review? | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review? | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review? | N/A | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 16 | Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review? | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of flaws in critical domains (answer: no) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Level of confidence: high, moderate, low and critically low | Low | Critically low | Low | Critically low | High | High | |

| ▭ 0 = no ▭ 1 = yes, partially ▭ 2 = yes, totally N/A = not applicable. | |||||||

Synthesis of results

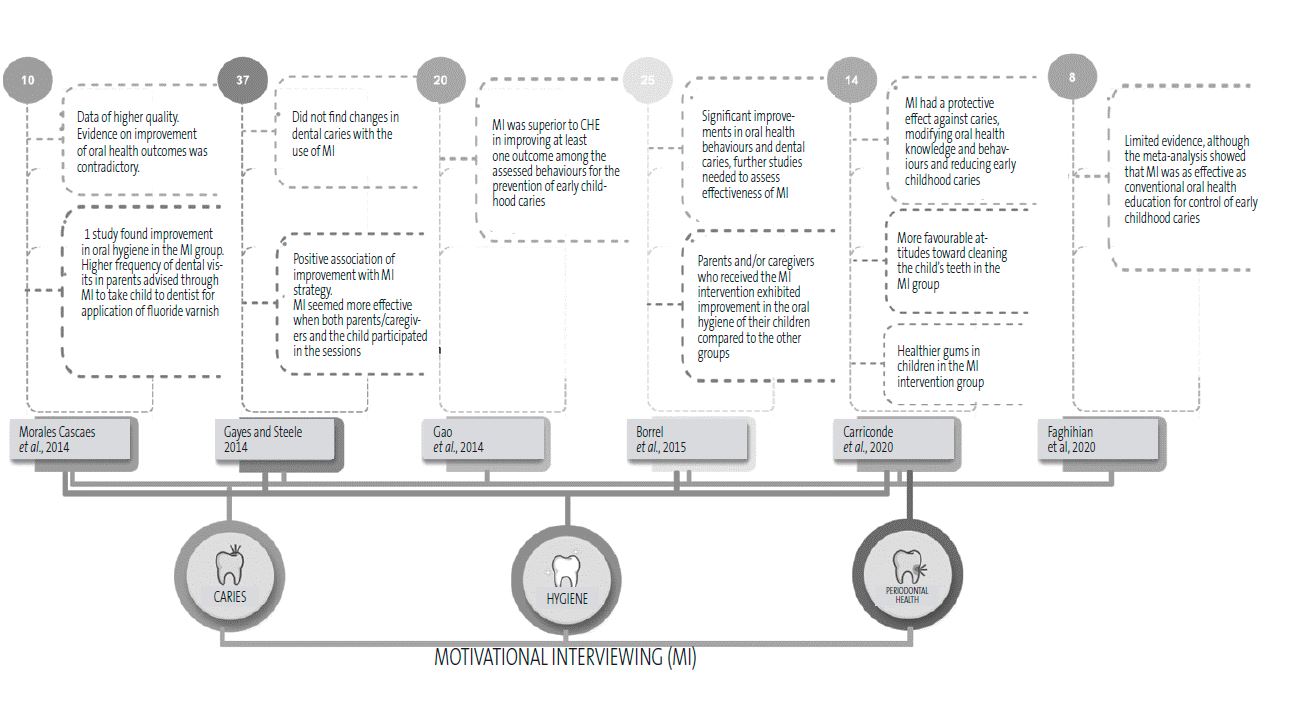

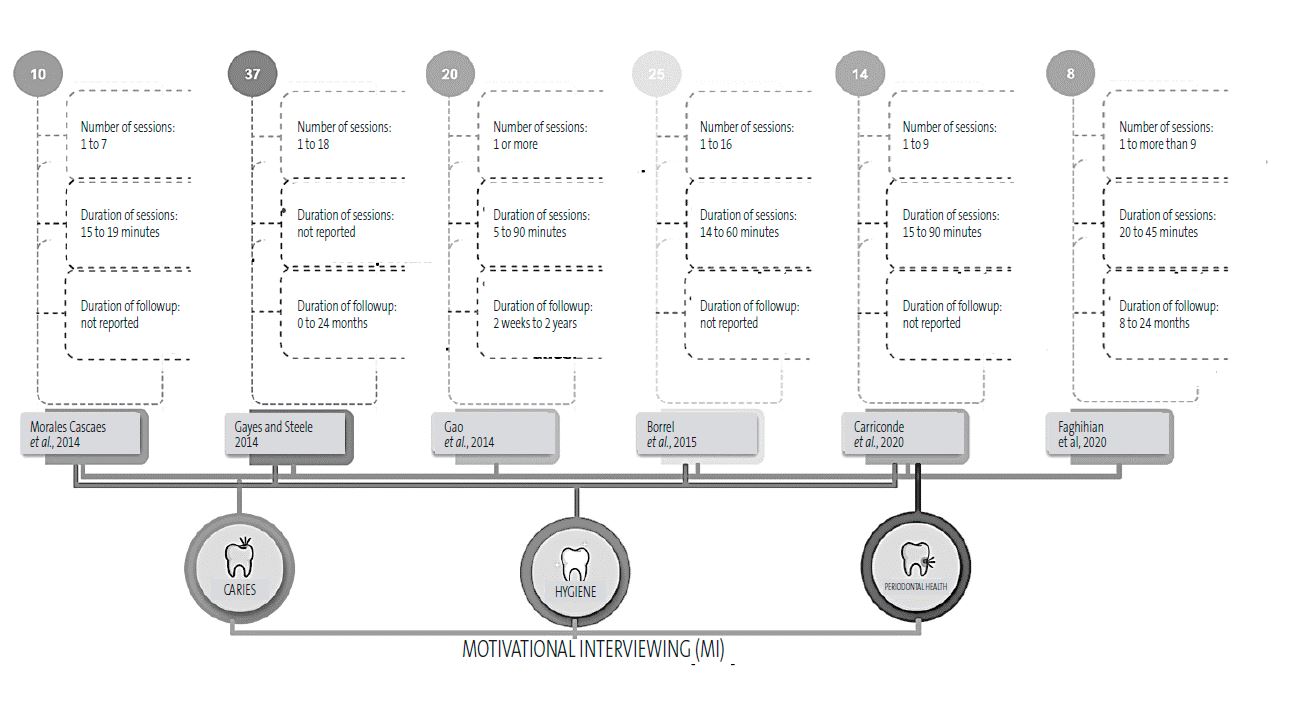

We made a graphic description of the methods used to synthesise the data in relationship maps (Figures 1 and 2) considering the types of study included in the SRs and MAs and grouping them by the oral and dental health outcomes they addressed, such as dental caries, oral hygiene or periodontal health in relation to the duration of the MI sessions.

RESULTS

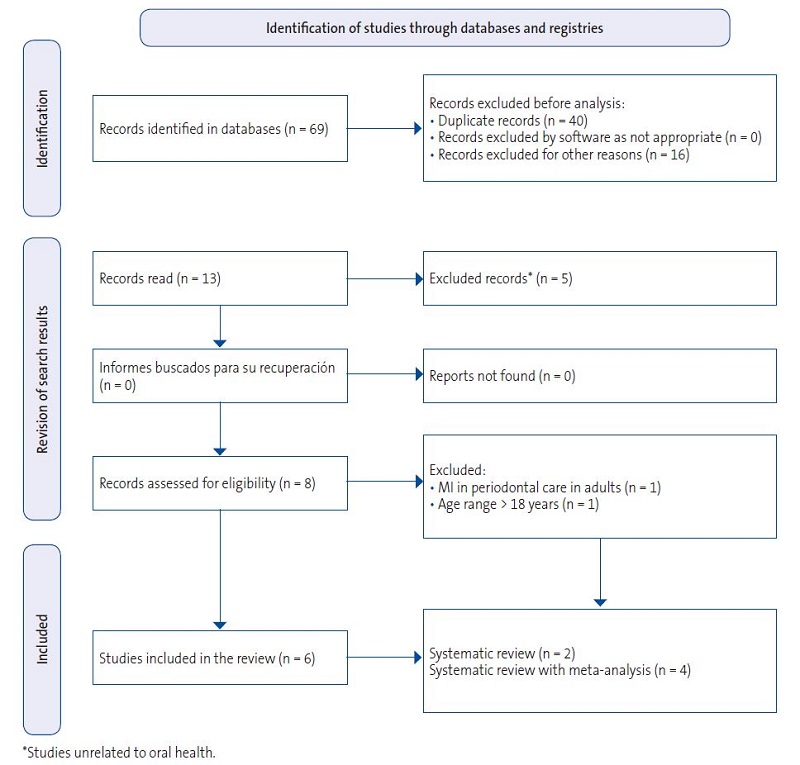

The search yielded a total of 69 articles, of which 6 were selected for reading of the full text, so that the final review included 2 SRs and 4 SRs with MA that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 3). Table 3 details the included articles with the corresponding titles, year of publication, authors, journal, country where the study was conducted, type of study design and number of studies included in the review or meta-analysis.

| Table 3. Articles included in the umbrella review | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Year of publication | Authors | Journal | Country | Type of studies | Number of studies included | Included type of study design |

| Effectiveness of motivational interviewing at improving oral health: a systematic review | 2014 | Andreia Morales Cascaes, Renata Moraes Bielemann, Valerie Lyn Clark, Aluísio JD Barros | Rev Saúde Pública | Brasil | Systematic review of RCTs | 10 | Randomised controlled trials (RCAs) |

| A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing interventions for pediatric health behavior change | 2014 | Laurie A. Gayes, Ric G. Steele | J Consultar Clin Psychol | United States | Meta-analysis of interventional studies | 37 | Randomised controlled trials (RCAs) |

| Motivational Interviewing in Improving Oral Health: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials | 2014 | Xiaoli Gao, Edward Chin Man Lo, Shirley Ching Ching Kot, Kevin Chi Wai Chan | Journal of Periodontology | Hong Kong | Systematic review of RCTs | 20 | Randomised controlled trials (RCAs) |

| Motivational Interviewing for Parent-child Health Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | 2015 | Belinda Borrelli, Erin M Tooley, Lori AJ Scott-Sheldon | Pediatric Dentistry | United States | Systematic review of RCTs | 25 | Randomised controlled trials (RCAs) |

| Motivational interviewing for preventing early childhood caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 | Beatriz Carriconde Colvara, Daniel Demétrio Faustino-Silva, Elisabeth Meyer, Fernando Neves Hugo, Roger Keller Celeste, Juliana Balbinot Hilgert | Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology | Brazil | Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | 14 | Randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized controlled trials and community-based randomized controlled trials |

| Impact of motivational interviewing on early childhood caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis | 2020 | Reyhaneh Faghihian, Elham Faghihian, Azam Kazemi, Mohammad Javad Tarrahi, Mehrnaz Zakizade | Journal of the American Dental Association | England | Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | 8 | Randomised controlled trials (RCAs) |

|

RCT: Randomized controlled trial. |

|||||||

Dental caries and MI

Five studies assessed improvement in dental caries with the use of MI and reported contradictory results in terms of oral health outcomes. Gao et al.6 summarised studies that used DMFT index (sum of the number of Decayed, Missing due to caries, and Filled Teeth), while other studies used the DMFS index (decayed, missing, and filled permanent teeth or surfaces). Motivational interviewing performed better than conventional health education (CHE) in the improvement of at least 1 outcome among the analysed behaviours for caries prevention in early childhood in the reviewed studies.

Colvara et al.10 reported that MI had a protective effect against caries in 4 studies included in their review due to its potential to modify oral health knowledge and behaviours, chiefly in early childhood caries, with a stronger impact in children with a significant caries history.

On the other hand, most of the studies analysed by Faghihian et al.11 found limited evidence of change. Although the results of the MA showed that IM interventions were as effective as dental health education for control of caries in early childhood, studies with better designs are required to assess the impact of MI more accurately. The review of Gayes et al.12 did not find changes in dental caries with the use of MI.

Oral hygiene and MI

Only 4 of the included articles took into account the assessment of changes in oral. Cascaes et al.13 reported on a single study that found improvement in oral hygiene in the intervention group (MI) compared to the control group. In addition, there was a significant improvement in the number of fluoride varnish applications in the parents in whom MI was used to recommend taking their child to the dentist to apply fluoride.

Borrelli et al.14 reported that oral hygiene habits improved in children whose parents and/or caregivers that underwent the MI intervention for education compared to the other groups. Colvara et al.10 analysed variables such as the frequency of brushing and the knowledge of toothpaste quantity and found more favourable attitudes towards cleaning the child’s teeth in the groups that received the MI-based intervention.

Gayes et al.12 assessed the overall effectiveness of IM for achieving change towards healthy behaviours and found a positive correlation with the MI strategy. In addition, they concluded that that MI was most effective when both parents/caregivers and the child participated in the sessions and when the provider and the family had the same cultural background.

Periodontal health and MI

The studies that assessed changes in periodontal health were conducted in adults and adolescents10,13,14; Colvara et al. analysed gum disease outcomes and found healthier gums in children in the MI group.10

Other health conditions and MI

Borrelli et al.14 found that participants, parents and caregivers subject to the MI intervention exhibited improvement in behaviours related to the health of the children by the end of the intervention, such as an increase in physical activity, a decreased screen time, improved diets and a lower body mass index (BMI); the authors also considered that MI was a suitable approach to change paediatric health behaviours in conditions such as type 1 diabetes and asthma and found that MI was most effective when both parents and children participated in the sessions and when the provider and the family had the same cultural background.

Followup in MI strategy applied to oral health

There was no consistency in the number of interventions, the duration of each session or the duration of followup in MI-based education strategies. The number of sessions ranged from 1 to 16; two studies reported between 1 and 7 sessions,14,15 one reported a single session6 and another 1 to more than 9 sessions.11 Colvara et al.10 reported the duration of followup of the reviewed studies, which ranged from 4 weeks for the shortest to 3 years for the longest, with the rest reporting followups of 1 to 24 months,14 8 to 24 months,16 3 to 6 months,17 and Gao et al. reported an average of 1 year.6 Borrelli et al.14 did not report data on the duration of followup.

Four of the analysed studies included the duration of IM sessions: Cascaes et al.13 reported 15 to 90 minutes, Borrelli et al.14 14 to 60 minutes, Gao et al.6 5 to 90 minutes and Faghihian et al.11 20 to 45 minutes. All SRs, based on the reported duration of the sessions, described a positive effect in terms of changing behaviours related to oral health indicators in children that underwent the IM intervention.

DISCUSSION

Studies that “review reviews”, commonly known as umbrella reviews (URs), are not frequent in the biomedical literature, and very few exist in the field of oral health, in which the secondary literature chiefly consists of MAs; however, to be considered the cornerstone of evidence, URs need to be developed with rigorous methodology.18 Thus, the application of the results of a SR or MA to clinical practice necessarily depends on the quality of the publication. Research that pools results from different study designs seeks to strengthen the results obtained in small samples, increasing statistical power and reinforcing the findings.

This umbrella review assessed whether MI was effective in improving oral health in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers based on the duration of the followup. We found that MI was effective in preventing early childhood caries compared to other educational strategies, including conventional health education. We also found a positive correlation between MI and changes in oral health, chiefly on account of improvements in oral hygiene and an increased frequency of dental visits.

In recent years, new evidence has been published on the subject of tooth decay prevention through MI; it is clear that when healthy habits are adopted, the risk of dental caries decreases.19 Among the known approaches currently used to change health behaviours, MI is an educational approach that can be considered effective insofar as it is not prescriptive. Gao et al.6 published the first SR on MI in the context of oral health including randomised clinical trials on the subject that compared conventional health education based on prescriptive guidance with the MI approach, and found a positive impact of the latter on different oral health indicators.

As regards changes in periodontal health resulting from MI interventions, most studies have been conducted in adults; however, evidence from studies that included children have shown a low frequency of dental plaque and reduction in gum bleeding in the MI intervention group15,17-20 in addition to an improvement in self-efficacy (daily flossing and interdental cleaning),21 an important predictor of the success of this approach.22

Although there was variability in the duration of the intervention, most reviews found a positive impact on oral health behaviours in children with the use of MI, independently of the duration of sessions and the duration of followup, whether the study evaluated 1 month of guidance23 or 8 to 12 months.24

Motivational interviewing was also effective in modifying other behaviours, such as a reduction in the habit of toothbrush sharing,23 which has been described in the literature as a probable risk factor for the transmission of oral diseases, as well as improvement in the followup of identified caries by the mothers of the affected children25 There were also changes in the knowledge of the correct toothpaste quantity and the safest time to give sugary snacks or drinks to children associated with MI.24

Several studies found a reduction in the dental surfaces affected by caries and therefore lower dental caries indices,7 a decrease in the dental plaque index,28-30 increased visits to dental providers for preventive fluoride application27 and a lesser extension and severity of dental caries (lesions involving dentin and pulp).28 Motivational interviewing seems to be an important alternative approach to guide behavioural change leading to a decrease in the DMFT index (Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth).30

The limitations of the study result from the heterogeneity of the evidence in terms of the sample size and selection process, the assessed outcomes and the delivered IM sessions, which did not allow deriving stronger evidence, which is the purpose of conducting SRs, MAs or URs.

In the general review, we assessed the quality of the research by means of the AMSTAR-2 instrument, which was developed to assess SRs of randomised and nonrandomised controlled trials and yields a general score based on the amount and degree of weaknesses in crucial domains; of the 6 included reviews, 2 had scores indicative of a critically low confidence in the results, 2 of a moderate confidence and 2 of a high confidence, which implies a lack of high-quality studies with an appropriate MI intervention analysing the impact on oral health outcomes in children aged 0 to 12 years and their caregivers.

We performed an exhaustive search of 5 electronic databases to avoid missing any relevant SRs; two authors selected the studies and extracted data independently and in duplicate, and discrepancies were resolved by a third author; we used the AMSTAR-2 as a tool for the critical evaluation of SRs in our umbrella review.

Future recommendations

Experimental studies focused mainly on the number of sessions, duration of sessions, duration of followup and professional implementing MI of children and caregivers will be important for future research on the subject. Future studies should report periodontal and gum health outcomes in children and with standardised data collection on specific outcomes (household socioeconomic status, educational attainment, whether the clinic is public or private, collection of data in person, through an online form or through the telephone) and apply the PRISMA checklist in the development of the manuscript.

CONCLUSION

Our review of previously published literature reviews showed that MI was effective for prevention of caries in early childhood, supporting the recommendation of this approach as part of the preventive measures applied chiefly in populations with a high risk of dental caries. It was also effective in improving oral health habits in children and caregivers. Future reviews should also include data on measures of dental plaque, periodontal conditions and the duration of followup to accurately assess the impact of MI interventions in children and their caregivers.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

CHE: conventional health education · MI: motivational interviewing · MIOH: motivational interviewing for oral health · MA: meta-analysis · PICO: Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome · PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses · SR: systematic review.

REFERENCES

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Ther. 1983;11(2):147–72.

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivationals Interviewing in Healthcare. New York: Guilford Press; 2008 [online] [consultado el 09/02/2024]. Available at www.academia.edu/48408809/

- Harrison R. Motivational interviewing (MI) compared to conventional education (CE) has potential to improving oral health behaviors. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14(3):124-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.07.012

- Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. PEC. 2013;93(2):157-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012

- Stewart JE, Wolfe GR, Maeder l, Hartz GW. Changes in dental knowledge and self-efficacy scores following interventions to change oral hygiene behavior. PEC. 1996;27(3):269-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012

- Gao X,Lo EC, Kot SC, Chan KC. Motivational interviewing in improving oral health: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JPER. 2014;85(3):426-37. https://doi.org/1902/jop.2013.130205

- Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Mental Health. 2018;21(3):95-100. https://doi.org/1136/ebmental-2018-300014

- Pagea MJ, McKenziea JE, Bossuytb PM, Boutronc I, Hoffmannd TC, Mulrowe CD, et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev Esp de Cardiol. 2022;75(2):790-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR-2: Herramienta de evaluación crítica de revisiones sistemáticas de estudios de intervenciones de salud. BMJ 2017;358.j4008. https://doi.org/1136/bmj.j4008

- Colvara BC, Faustino-Silva DD, Meyer E, Neves Hugo F, Keller Celeste R, Balbinot Hilger J. Motivational interviewing for preventing early childhood caries: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020;00:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12578

- Faghihian R, Faghihian E, Kazemi A, Tarrahi MJ, Zakizade M. Impact of motivational interviewing on early childhood caries A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020:151(9):650-9. https://doi.org/1016/j.adaj.2020.06.003

- Gayes LA, Steele RG. A metaanalysis of motivational interviewing interventions for pediatric health behavior change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3):521-53. https://doi.org/1037/a0035917

- Cascaes AM, Bielemann RM, Clark VL, Barros AJ. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing at improving oral health: A systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(1):142-53. https://doi.org/1590/s0034-8910.2014048004616

- Borrelli B, Tooley EM, Scott-Sheldon l. Motivational Interviewing for Parent-child Health Interventions: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(3):254-65.

- Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Lindberg P, Oscarson N. Evaluation of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on periodontal health. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(10):912-9. https://doi.org/1111/j.1600-051X.2010. 01590.x

- Jönsson B, Öhrn K, Oscarson N, Lindberg P. The effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on oral hygiene behaviour in patients with periodontal disease: A blinded randomized-controlled clinical trial (one-year follow-up). J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(12):1025-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01453.x

- Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Lindberg P, Oscarson N. Evaluation of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on periodontal health. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(10):912-9. https://doi.org/1111/j.1600-051X.2010. 01590.x

- Chambergo Michilot D, Díaz Barrera ME, Benites Zapata VA. Revisiones de alcance, revisiones paraguas y síntesis enfocada en revisión de mapas: aspectos metodológicos y aplicaciones. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2021;38(1):136-42. https://doi.org/10.17843/ rpmesp.2021.381.6501

- Freudenthal JJ, Bowen DM. Motivational interviewing to decrease parental risk-related behaviors for early childhood caries. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84:29-34.

- Jönsson B, Ohrn K, Lindberg P, Oscarson N. Cost-effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme based on cognitive behavioural strategies in non-surgical periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(7):659-65. https://doi.org/1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01898.x

- Lalic M, Aleksic E, Gajic M, Milic J, Malesevic D. Does oral health counselling effectively improve oral hygiene of orthodontic patients? EJPD. 2012;13(3):181-6

- Wright KS. Engaging Families Through Motivational Interviewing. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2014;61:907-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2014.06.014

- Woelber JP, Spann-Aloge N, Hanna G, Fabry G, Frick K, Brueck R, et al. Training of dental professionals in motivational interviewing can heighten interdental cleaning self-efficacy in periodontal patients. Front psychol. 2016;7:254. https://doi.org/3389/fpsyg.2016.00254

- Naidu R, Nunn J, Irwin JD. The effect of motivational interviewing on oral healthcare knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of parents and caregivers of preschool children: an exploratory cluster randomised controlled study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-015-0068-9

- Vanbuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-80. https://doi.org/1007/s10865-013-9527-4

- Ismail AI, Ondersma S, Jedele JM, Little RJ, Lepkowski JM. Evaluation of a brief tailored motivational intervention to prevent early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39(5):433-48. https://doi.org/1111/j.1600-0528.2011. 00613.x

- Harrison R, Benton T, Everson-Stewart S, Weinstein P. Effect of motivational interviewing on rates of early childhood caries: a randomized trial. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(1):16-22.

- Harrison RL, Veronneau J, Leroux B. Effectiveness of maternal counseling in reducing caries in Cree children. J Dent Res. 2012;91(11):1032-7. https://doi.org/1177/0022034512459758

- Saengtipbovorn, S. Efficacy of motivational interviewing in conjunction with caries risk assessment (MICRA) programmes in improving the dental health status of preschool children. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2017;15(2):123-9. https://doi.org/3290/j.ohpd.a37924

- González del Castillo-McGrath M, Guizar Mendoza JM, Madrigal Orozco C, Anguiano Flores l, Amador Licona. A parent motivational interviewing program for dental care in children of a rural population.J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6(5):e524-e529. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.51662