Vol. 22 - Num. 86

Original Papers

Perianal streptococcal dermatitis: clinical and epidemiological study of 95 episodes

Jacinto Martínez Blancoa, Laura Míguez Martínb, Noelia Valverde Pérezc

aPediatra. CS El Coto. Gijón. Asturias. España.

bPediatra. Área V. Gijón. Asturias. España.

cMIR-Pediatría. Hospital de Cabueñes. Gijón. Asturias. España.

Correspondence: J Martínez. E-mail: jacintomartinezblanco@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Martínez Blanco J, Míguez Martín L, Valverde Pérez N. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis: clinical and epidemiological study of 95 episodes. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:131-8.

Published in Internet: 25-05-2020 - Visits: 32333

Abstract

Introduction and objectives: to analyse the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of perianal dermatitis cases caused by group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus (GABHS).

Material and methods: prospective case series with collection of data for a period of 8 years in an outpatient paediatrics clinic.

Results: there were 95 episodes (1/298 visits) diagnosed in 76 children (predominantly boys, 1.6/1). The mean age was 4.5 years. Thirteen patients had more than one episode, with a total of 19 recurrent episodes, 10 of them within 6 months of the previous episode (11% of the total number of episodes). The most frequent presenting complaints were itching, bleeding, pain, constipation and perianal erythema. Treatment was topical in 70% of the initial episodes, and combination therapy (topical and systemic) was used in 68% of recurrent episodes. The initial treatment failed in 3 cases. The seasonal case distribution was similar to that of pharyngotonsillitis and scarlet fever caused by GABHS in the same time period.

Conclusions: five presenting complaints (itching, bleeding, pain, constipation and perianal erythema), alone or in combination, were present in 92% of the episodes. Perianal erythema was the presenting complaint in only 17% of the first episodes. Erythema can be faint and its borders are not always well demarcated, and may manifest with associated satellite lesions.

Keywords

● Erythema ● Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus ● Perianal dermatitis ● Perianal streptococcal dermatitisINTRODUCTION

In 1966, Amren et al.1 described a novel disease associated with group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABHS) that they labelled perianal cellulitis. In 1987, Kokx et al.2 proposed renaming it streptococcal perianal disease, as it did not consistently present with cellulitis. In 1993, Montemarano et al.3 published a case associated with Staphylococcus aureus. Several authors have used the term streptococcal dermatitis or perianal streptococcal disease, as it may be associated with infection in this region.

Perianal dermatitis in children is usually caused by GABHS and less frequently by group B, C or G beta-haemolytic streptococcus4,5 or Staphylococcus aureus,3,6 among other pathogens. Its incidence has been estimated at 1/3007 to 1/20001 paediatric visits and may be currently underestimated. It affects boys more often, and the mean patient age is 3 to 5 years.8-10

It typically presents with perianal erythema with clear boundaries (90%-100%), occasionally with satellite lesions and possibly extending to the intergluteal region; perianal itching (50%-100% of cases); rectal pain or pain during bowel movements (17%-50%); bloody stools (13%-50%); constipation (15%-50%); anal fissures (10%-50%) and irritability.11 It may be associated with abdominal pain, guttate psoriasis, vulvovaginitis, balanoposthitis, atopic dermatitis, dysuria, perianal exudate and scarlatiniform rash.12,16 There are no systemic manifestations.

Of all patients with perianal dermatitis, 30% to 95% are pharyngeal carriers or have streptococcal pharyngitis. Only 6% of pharyngitis due to GABHS occur in perineal carriers,17 and it is not possible to determine whether pharyngeal colonization predated or followed perianal colonization.2,18,19. Fewer than 1% of healthy children are perianal carriers of this bacterium.17

There are various hypothesis regarding its route of transmission: bath water, gastrointestinal or airborne, healthy carriers, fomites, self-inoculation... There have been descriptions of household clusters and outbreaks in childcare centres and hospitals.4,20,21

The diagnosis is made based on the clinical manifestations and physical examination. It is confirmed either with the rapid GABHS antigen detection test (sensitivity: 77.9%-98%, specificity: 73%-100% for extrapharyngeal samples9,22), or by culture (indicating to the laboratory the tests that need to be performed).19,20,23

The differential diagnosis includes diaper rash, intestinal parasitosis, candidiasis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, histiocytosis, zinc deficiency, lichen sclerosus, haemorrhoids and sexual abuse, among other conditions.

Treatment achieves quick improvement of symptoms and can be systemic with administration of oral antibiotics (mainly penicillin or amoxicillin, as other alternatives have not been studied, save for cefuroxime24), topical (mainly fusidic acid or mupirocin) or both simultaneously. Recurrence is frequent, especially in case of exclusive oral treatment.

The main objective of the study was to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of perianal dermatitis cases in a primary care paediatrics clinic. Our secondary objective was to evaluate the temporal association of perianal dermatitis with pharyngeal infections by GABHS and the incidence of recurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a prospective longitudinal observational and descriptive study of the series of perianal dermatitis cases positive for GABHS diagnosed between 01/04/2011 and 31/03/2019 in the paediatrics clinic of a primary care centre in Gijon (Asturias, Spain) serving children aged 0 to 13 years.

We included patients whose presenting complaints or in who the findings of the physical examination were consistent with perianal dermatitis and with positive detection of GABHS in a perianal sample with a rapid antigen test (OSOM Strep A kit, Genzyme). We collected data for the following: date of visit, health record number, age, sex, reason for visit, clinical manifestations, findings of physical examination, treatment and recurrence. The same researcher performed the examination of the perianal region in all cases, classifying the erythema based on its extension and intensity: no erythema, minimal (barely perceptible), mild (limited extension and intensity), moderate (more spread or intense than mild and less than severe) and severe (widely spread and intense).

We analysed the number of recurrences with a positive GABHS test result in successive visits and 2 months after completing the data collection, we reviewed the health records and contacted the families by telephone.

We retrospectively determined the total number of visits (excluding successive visits for a single episode and phone consultations), the dates of visits, and the age and sex of patients with a diagnosis of pharyngotonsillitis or scarlet fever with a positive GABHS test managed in our clinic over the same time period.

We have summarised quantitative data as mean and standard deviation, and qualitative data as percentages. For hypothesis testing, we used the Student t test (to compare the behaviour of a quantitative variable in two groups) and contingency tables and the Pearson χ2 test to assess the association between qualitative variables. In case of 2 x 2 tables, we used the Fisher exact test.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias. We obtained the informed consent of the parents or guardians of the patients as well as the consent for taking photographs. Since this was not an interventional or experimental study, all parents consented to participation.

RESULTS

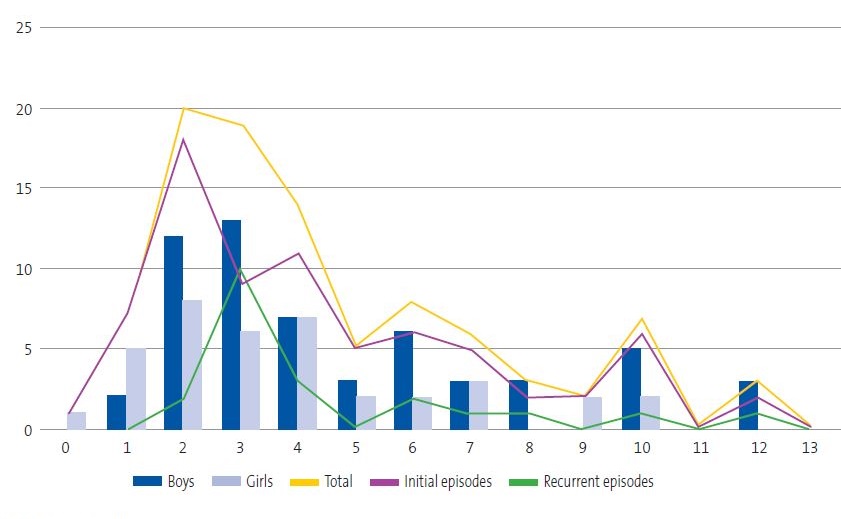

In the period under study (8 years), the clinic managed 28 328 initial visits, with diagnosis of 95 episodes of perianal dermatitis (1/298 visits) confirmed by a GABHS detection test in 76 children, 62% male and 38% female (a difference that was statistically significant; p = 0.0034), with no significant association between age and sex (p = 0.2416) (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Distribution of perianal streptococcal dermatitis cases by age, sex and type of episode |

|---|

|

The most frequently documented presenting complaints were itching, perianal bleeding or bleeding on bowel movements, constipation and erythema (Table 1). Less frequent symptoms included fissures (6 episodes), fever (in every case accompanied by painful swallowing and a positive GABHS test in pharyngeal swab samples), painful swallowing, vulvitis-vulvar discharge (four episodes), abdominalgia, rule out intestinal parasites (3 episodes), dysuria (2 episodes), diaper rash, balanitis, paraphimosis, folliculitis, encopresis, mass, rule out haemorrhoids (1 episode each).

| Table 1. Main presenting complaints based on frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting complaint | % | Mean age, total sample (male/female) | Initial episodes/recurrent episodes |

| Itching | 41 | 5.1 (5.3/4.6) | 5.3/4.4 |

| Bleeding | 37 | 5.2 (5.7/4.3) | 4.9/6.6 |

| Pain | 27 | 3.5 (4.8/2.2) | 3.7/2.8 |

| Constipation | 25 | 3.3 (3.4/3.3) | 3.4/3 |

| Erythema | 1 | 4.3 (4.1/4.8) | 4.5/3.7 |

Sixty-three children had only 1 episode and 13 (8 male, 5 female; 17% of the total episodes) had more than 1 (10 patients had 2 episodes and 3 patients had 3, 4 and 5 episodes respectively). We detected 10 recurrent episodes that occurred within 6 months of the previous episode (11% of the total) and 9 that occurred after 6 months. Recurrent episodes had onset between 24 and 740 days after the previous episode (mean: 265 days).

In the subset of initial episodes, we did not find a statistically significant association between sex (χ2 0.0006, p = 0.9803), age (Welch t = 0.641, p = 0.537), or any of the 5 main presenting complaints (pain, p = 0.6771; erythema, p = 1; constipation, p = 0.67771; itching, p = 0.1368; bleeding, p = 0.1358) and recurrence within 6 months.

When we assessed the association between each of the 5 most frequent presenting complaints in the group of first episodes and patient sex, we found that perianal erythema was more frequent in boys (25.5%) compared to girls (3.4%) (p = 0,0132); as was itching (48.9/24.1%; p = 0.0523), with no significant differences in the others (pain, p = 0.3059; constipation, p = 0.3059; bleeding, p = 1). When we assessed the association with patient age, we found a younger age in patients presenting with constipation (p = 0.0355) and older age in patients with itching (p = 0.0038); with no significant differences in the other presenting complaints (pain, p = 0.1610; bleeding, p = 0.3138; erythema, p = 0.8714). When we analysed the presenting complaint in relation to age and sex, we found that girls sought care for pain at a younger age compared to boys (2.2/5.0; p = 0.0019), and found no significant differences for any of the other complaints (bleeding, p = 0.1979, constipation, p = 0.7418; itching, p = 0.2547).

The observed symptoms that were not the chief complaint were constipation in 17 additional cases, perianal pain or pain on bowel movements in 4, erythema in 2, bloody stools or perianal bleeding in 3 and itching in 1.

Erythema was absent in 7 cases, minimal in 14, mild in 38, moderate in 20 and severe in 15 (Figure 2); the intensity of erythema was not documented in 1 case. There were satellite lesions in 8 episodes (Figure 3), vesicles in 3 and poorly demarcated boundaries in 3.

The time elapsed from onset to diagnosis was documented in 37 episodes, and was 1 week or less in 30 episodes, 2 weeks in 3 episodes, 3 weeks in 1 episode and 4 weeks in 3 episodes.

Exclusive topical treatment was used in 59 episodes (62% of the total), corresponding to 53 initial episodes (70% of these episodes) and 6 recurrent episodes (32%). Fusidic acid was used in 53 episodes and mupirocin in 6.

Combination therapy (topical and systemic via the oral route) was used in 36 episodes (38% of the total), 23 of initial episodes (30%) and 13 of recurrent episodes (68%). It consisted of amoxicillin and fusidic acid in 26, amoxicillin and mupirocin in 9 and cefuroxime and mupirocin in 1.

Treatment had to be modified in 3 patients in whom the initial treatment failed (3%):

- Episode 38: treatment with fusidic acid with subsequent addition of amoxicillin due to treatment failure. Since symptoms persisted and the followup GABHS test on a perianal sample was positive, treatment was modified with initiation of cefuroxime and maintenance of fusidic acid, with resolution of symptoms and a negative test in the followup. This patient had 3 recurrent episodes 21, 29 and 31 months after the initial episode.

- Episode 75: treatment with fusidic acid, positive follow-up test. Amoxicillin was added, and due to persistence of positive test result, switched to cefuroxime. No recurrence.

- Episode 95: fifth episode. Treatment: cefuroxime and mupirocin, with no clinical response and persistence of positive GABHS test. Switched to oral antibiotherapy with amoxicillin with addition of rifampicin the last 4 days (regimen similar to the one described by Kokx2 for persistent cases), with a subsequent negative follow-up test. No more episodes documented to date.

There were recurrent episodes in 15/59 cases managed with topical treatment and 4/36 of cases managed with combination therapy.

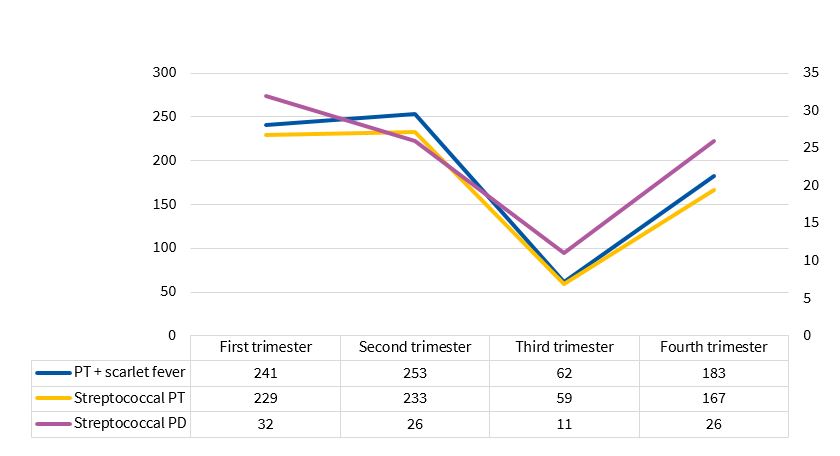

We detected a seasonal pattern , with a statistically significant decline in the third trimester (p = 0.0174), a distribution that was similar to that of pharyngotonsillitis (p = 0.0000) and pharyngotonsillitis associated to scarlet fever with a positive GABHS test in the same time period (p = 0.0000) (Figure 4), with a ratio of 1 case of perianal dermatitis caused by GABHS per every 7.8 cases of pharyngotonsillitis and scarlet fever with a positive GABHS test (1/7.3 if we excluded cases of scarlet fever).

| Figure 4. Seasonal distribution of streptococcal infections |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

The main objective of our study was to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of cases of perianal dermatitis caused by GABHS, and we found a frequency of initial visits due to this complaint similar to the frequency reported by Mogielnicky et al. (1/300).7

We found a predominance of the male sex, as has been described in the literature, although the proportion of male patients was lower compared to some of the reviewed articles8,10 and similar to the proportion reported in others.12,13

The mean age was similar to the mean age reported by other authors. We did not find differences in the sex distribution of patients between first episodes and recurrent episodes, which was consistent with the findings of Clegg et al.18 and Olson et al.10.

The clinical manifestations, including bleeding (40%), constipation (48%), itching (42%; more frequently in male patients), pain (32%; more frequent in female patients) and fissures (16%), were consistent with the reviewed literature.

Erythema was the presenting complaint in fewer than 50% of cases, which was consistent with the findings of Mogielnicky et al.7

In 21 out of 94 cases (22%) the erythema was absent or minimal (may be overlooked), and few patients presented with satellite lesions, vesicles or poorly demarcated edges (13%), which are not reasons to rule out this diagnosis.

Although further studies are required (as our study was not designed with this objective in mind), exclusive topical treatment may suffice in most cases (in the 2 patients in whom topical treatment failed, subsequent combination therapy was ineffective and required another switch) and offers the added benefit of covering potential coinfection with other bacteria.

The number of recurrences was in the lower limit of the range found in the reviewed literature (11%-44%), probably on account of the short mean time elapsed from onset of symptoms and diagnosis (predictors for recurrence include longer time elapsed from onset and a history of streptococcal infection in a first-degree relative 13,18) and treatment not having been limited exclusively to oral drugs.

The observed seasonal distribution was consistent with the previous literature and with the pattern observed in the distribution of GABHS tonsillitis.4,6,25

There were limitations to our study: the data were collected in a single visit and the sole means used to confirm the clinical diagnosis was the test for detection of GABHS. The degree of erythema was assessed subjectively, although the assessment was always made by the same researcher. Patients were not randomly allocated to treatment groups due to the merely observational nature of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

We found statistically significant differences in the sex distribution of dermatological complaints.

Five chief complaints (itching, bloody stools or perianal bleeding, perianal pain or pain on defecation, constipation and perianal erythema), alone or in combination, were present in 92% of the cases. When we analysed the association of the presenting problem with sex, we found that male patients sought care more frequently for perianal erythema and itching, and when we analysed the association with age, we found that constipation was associated with younger age and itching with older age. In girls, pain was the presenting complaint at a younger age compared to boys.

Perianal erythema was the presenting complaint in only 17% of patients with a first episode. In the physical examination, perianal erythema may not be present or may be very mild in a substantial proportion of cases. Its borders are not always well-defined and there may be satellite lesions or vesicles, so if the clinical manifestations are highly suggestive, the diagnosis should be confirmed, since in case of a positive result outcomes are very good with adequate treatment.

Although the study was not designed to analyse this aspect, it appears that initial treatment with topical agents alone may be sufficient, given the low failure rate of this approach and the fact that in 2 patients that did not respond to it the initial combination therapy regimen (topical + oral) also failed, while we are unable to draw conclusions regarding recurrence.

The seasonal distribution is similar to that of streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis, with a decline in the third trimester of the year.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

GABHS: Group A β-haemolytic streptococcus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank professor Norberto Octavio Corral Blanco (Chair of Statistics of the Universidad de Oviedo), for his contribution to the statistical analysis of the data.

REFERENCES

- Amren DP, Anderson AS, Wannamaker LW. Perianal cellulitis associated with group A streptococci. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:546-52.

- Kokx NP, Comstock JA, Facklam RR. Streptococcal perianal disease in children. Pediatrics. 1987;80:659-63.

- Montemarano AD, James WD. Staphylococcus aureus as a cause of perianal dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:259-62.

- Zhang C, Haber RM. The ABCs of perineal streptococcal dermatitis. Case, series and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:102-7.

- Šterbenc A, Seme K, Lah LL, Točkova O, Trop TK, Svent-Kucina, et al. Microbiological characteristics of perianal streptococcal dermatitis: a retrospective study of 105 patients in a 10-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2016;25:73-6.

- Heath C, Desai N, Silverberg NB. Recent microbiological shifts in perianal bacterial dermatitis: Staphylococcus aureus predominance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:696-700.

- Mogielnicki NP, Schwartzman JD, Elliott JA. Perineal group Streptococcal disease in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2000;106:276-81.

- Mostafa WZ, Arnaout HH, El-Lawindi MI, El-Abidin YZ. An epidemiologic study of perianal dermatitis among children in Egypt. Dermatol. 1997;14:351-4.

- Cohen R, Levy C, Bonacorsi S, Wollner A, Koskas M, Jung C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical symptoms and rapid diagnostic test in-group A streptococcal perianal infections in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:267-70.

- Olson D, Edmonson MB. Outcomes in children treated for perineal group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal dermatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:933-6.

- Shouval DS, Schurr D, Nussinovitch M. Presentation of perianal group a streptococcal infection as irritability among children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:568-70.

- Redondo Mateo J, Carrero González PA, Sierra Pérez E. Dermatitis estreptocócica perianal. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2002;93:243-6.

- Echevarría Fernández M, González Martínez F, Marañón Pardillo R. Factores epidemiológicos implicados en la enfermedad perianal estreptocócica. An Pediatr (Barc). 2009;70:511-2.

- García-Osés I, Martínez de Zabarte Fernández JM, Puig García C, Arnal Alonso JM. Pensando en la dermatitis perianal. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015;17:51-5.

- Patrizi A, Costa AM, Fiorillo L, Neri I. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis associated with guttate psoriasis and/or balanoposthitis: a study of five cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:168-71.

- Honig PJ. Guttate psoriasis associated with perianal streptococcal disease. J Pediatr. 1988;113:1037-9.

- Asnes RS, Vail D, Grebin B, Sprunt K. Anal carrier rate of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci in children with streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 1973;52:438-41.

- Clegg HW, Giftos PM, Anderson WE, Kaplan EL, Johnson DR. Clinical perineal streptococcal infection in children: epidemiologic features, low symptomatic recurrence rate after treatment and risk factors for recurrence. J Pediatr. 2015;167:687-93.

- Krol AL. Perianal streptococcal dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1990;7:97-100.

- Herbst RA. Perineal streptococcal dermatitis/disease recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:555-60.

- Barzilai A, Choen HA. Isolation of group A streptococci from children with perianal cellulitis and from their siblings. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:358-60.

- Clegg HW, Dallas SD, Roddey OF, Martín ES, Swetenburg RL, Koonce EW, et al. Extrapharyngeal group A Streptococcus infection: diagnostic accuracy and utility of rapid antigen testing. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:726-31.

- Spear RM, Rothbaum RJ, Keating JP, Blaufuss MC. Perianal streptococcal cellulitis. J Pediatr. 1985;107:557-9.

- Meury SN, Erb T, Schaad UB, Heininger U. Randomized, comparative efficacy trial of oral penicillin versus cefuroxime for perianal streptococcal dermatitis in children. J Pediatr. 2008;153:799-802.

- Echevarría Fernández M, López-Menchero Oliva JC, Marañón Pardillo R, Míguez Navarro C, Sánchez Sánchez C, Vázquez López P. Aislamiento de estreptococo betahemolítico del grupo A en niños con dermatitis perianal. An Pediatr (Barc). 2006;64:153-7.