Vol. 18 - Num. 71

Original Papers

Impact of day-care centre attendance on frequency of primary care and emergency department visits

M.ª Ángeles Ordóñez Alonsoa, Begoña Domínguez Aurrecoecheab, José Ignacio Pérez Candásc, P López Vilard, Mercedes Fernández Francése, M.ª del Mar Coto Fuentef, A Aladro Antuñag, Francisco J Fernández Lópezh

aPediatra. CS La Corredoria. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA). Oviedo. Asturias. España.

bPediatra. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA). Asturias. España.

cPediatra. CS de Sabugo. Avilés. Asturias. España.

dPediatra. CS Puerta de la Villa. Gijón. Asturias. España.

eCS La Corredoria. Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA). Asturias. España.

fCS La Magdalena. Avilés. Asturias. España.

gPediatra. CS de Otero. Oviedo. Asturias. España.

hPediatra. CS de Nava. Nava. Asturias. España.

Correspondence: MA Ordóñez. E-mail: marigeloa@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Ordóñez Alonso MA, Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Pérez Candás JI, López Vilar P, Fernández Francés M, Coto Fuente MM, et al. Impact of day-care centre attendance on frequency of primary care and emergency department visits. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2016;18:243-52.

Published in Internet: 15-09-2016 - Visits: 25586

Abstract

Introduction: nurseries arise to meet a social need, but are not without influence on children’s health.

Patients and methods: prospective longitudinal study of two cohorts of children aged 0-24 months (they differ in attendance or not to care); attending consultations of 33 pediatricians of Public Health Service of Asturias. The data were obtained from the clinical history and interviews scheduled (6, 12, 18 and 24 months). They were compared: average number of visits to emergency rooms and pediatric, and influence of different variables collected. We analyzed: the registered morbidity (acute infections and recurrent wheezing) between frequent attenders (HF) and not HF.

Results: the average number of visits to pediatric visits is significantly higher for children attending kindergarten in all age groups studied. There is a greater percentage of HF among those attending nursery: children between 0 and 6 months that have a RR to come to be HF to emergency services up to 6 times higher than those not attending and RR 4 times more to be HF to pediatric primary care.

Conclusions: 1) attendance at kindergarten is associated with increased likelihood of being HF to Emergency and pediatric Primary Health Care services; 2) the HF children suffer more respiratory and infectious diseases, which are not explained by attending to a nursery, y 3) the above leads to higher drug consumption.

Keywords

● Child day care centers ● Health resources ● Morbidity ● Pediatrics ● Primary careINTRODUCTION

In 1956, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined day care as “an organized service for the care of children away from their own homes during some part of the day, when circumstances call for normal care in the home to be supplemented”.1

In Spain, based on population surveys conducted in 2010, 25.01% of women work outside the home and use specialized child-care services.2

Day-care centre attendance is not free from risks to the health of the child,3,4 and is associated with a considerable increase in the incidence of acute infections during childhood. A higher frequency of acute diseases involves an increased use of health care resources and medication. Thrane et al5 showed that the risk of undergoing treatment with antibiotics doubles during the first three months of day care attendance.

The increased incidence of infectious diseases also has an impact on society, as these diseases are transmitted to close contacts in the household.6,7

All of the above may result in an increased use of health care services, which is already high in the under-five population,8 and, considering that there are studies that have shown that past health care use is the best predictor for future health care use,9 it would be possible for inadequate use patterns to develop during childhood that would be maintained in adulthood.

Thus, we are facing a reality that has a considerable influence on the everyday health of children and on present and future health care expenditures (as it can lead to a higher risk of iatrogenic injury in children and produce strain on the public health system due to increased use of health care resources).

The aim of this study was to analyse the impact of day-care centre attendance on the demand for medical services and the development of patterns of frequent attendance. We also analysed the morbidity pattern (acute infectious disease and recurrent wheezing) of children that were frequent attenders (FAs).

OBJECTIVES

- To establish a statistical definition of patterns of frequent attendance in emergency departments and paediatric primary care (PPC) clinics.

- To establish the influence of the factors analysed in relation to frequent attendance:

- Child-related: sex, gestational age, birth weight, neonatal disease and vaccination history.

- Nutrition-related: breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding.

- Related to parents and socioeconomic status: number of siblings; and, for both parents, age, educational attainment and employment.

- To assess whether the “day care exposure” factor is associated with changes in health care use compared to previous use, and promotes overuse of health care services.

- To determine whether the pattern of morbidity is different in FAs.

SAMPLE AND METHODS

We conducted a longitudinal prospective study of two cohorts of children aged 0 to 24 months that differed solely on attending vs not attending day-care centres (exposure factor).

Participants: the study started with the participation of 35 paediatricians and 20 nurses employed in the eight health areas of the Public Health Service of the Principality of Asturias (Servicio Público de Salud del Principado de Asturias [SESPA]), who enrolled 1139 children in the study.

Inclusion criteria: children born between January 1 and September 30, 2010 that receive routine care in the PPC clinics of the SESPA and whose families consented to their participation after being thoroughly informed. Exclusion criteria: presence of respiratory or cardiovascular disease or severe immunodeficiency.

Study variables

Independent variable: day-care attendance (yes/no dichotomous variable), used to define the two cohorts. We documented the age (in months) at which attendance started, and the reasons for attendance.

Subject variables:

- Personal characteristics: code, date of birth, sex, gestational age, birth weight, history of neonatal disease, breastfeeding, immunization history including routine immunizations in the Autonomous Community of Asturias and elective immunizations (pneumococcal, rotavirus and varicella vaccines).

- Family characteristics: number of siblings; maternal and paternal age, educational attainment, employment status, smoking, history of allergies and asthma.

Dependent variables:

- Number and type of acute infections leading to a health care visit (to PC or ED services): bacteraemia, bronchiolitis, acute bronchitis, conjunctivitis, exanthematous viral diseases, , pharyngitis, pharyngotonsillitis, influenza, laryngitis, meningitis, pneumonia, acute otitis media, common cold, sepsis, recurrent wheezing episodes as defined in the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.

- Visits to Emergency and Paediatrics departments: we included all visits, even if they all corresponded to a single disease process. We excluded routine visits made in the context of the well-child programme.

- Drugs used: antibiotics, bronchodilators, inhaled and oral corticosteroids and montelukast.

Data collection

We collected the data from the electronic health records and through interviews with the parents at the PPC clinics scheduled at ages 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. Data for subject variables were collected during the first visit and outcome variables were collected during the visits at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months and documented in forms designed for that purpose. The informed consent signed by parents included an explicit statement on the adherence and compliance with legal and ethical principles.

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis, calculating the frequency distribution for qualitative variables and measures such as the mean, median and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables. We used Pearson’s chi square test for comparison of two qualitative variables, calculating the relative risk and the 95% confidence interval (CI) when the association was statistically significant (P < .05). We used Student’s or Welch’s t test to compare two means, and the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare more than two means. We assessed the normality of the distributions and differences in variance by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test and the Ansary-Bradley test, respectively. The statistical analysis was performed with the R® software (R Development Core Team, 2012) version 2.15.

RESULTS

We collected data for 1139 children at 6 months, 1092 at 12 months, and finally 975 at 24 months. The 14.3% of loss to followup was due to employment changes in three paediatricians (7.9%) and residence changes in children included in the sample (7.4%).

Homogeneity of the cohorts under study: both cohorts were homogeneous, except for parental educational attainment and maternal employment (parental college-level education and maternal employment outside the home were more frequent in the cohort that attended day care).

Pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccine coverage was higher in children that attended day-care centres.

Children that attended day care: 43.7% of the children in the study were enrolled in day care at age 2 years (most started attending at age 5 to 6 months). Parental employment was the reason for enrolment in day care in 90.7% of these children.

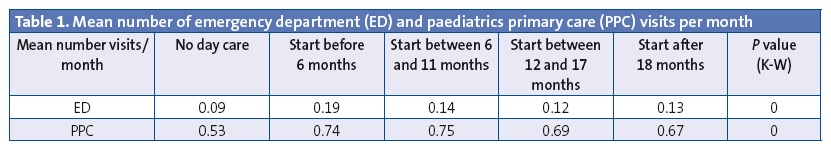

Number of visits to emergency or PPC services a month in both cohorts (Table 1):

- The number of visits per month was lower in children that did not attend day care compared to those that did (P < .05), regardless of the age at which day care attendance started. It is important to keep in mind that our study only analysed visits made due to infectious diseases or recurrent wheezing.

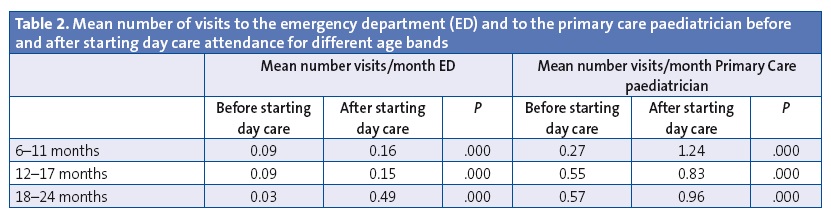

- To learn whether the “day care attendance” variable was associated with changes in the use of health care services, we analysed use by age bands to see whether enrolment in day care correlated to changes in the mean number of medical visits per month, and we found significant differences in all cases (Table 2).

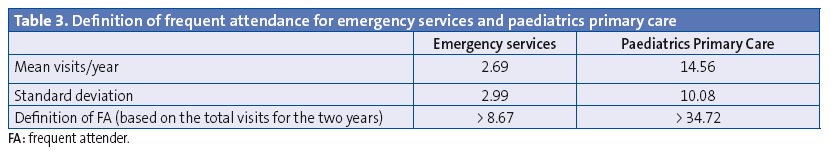

Definition of frequent attenders

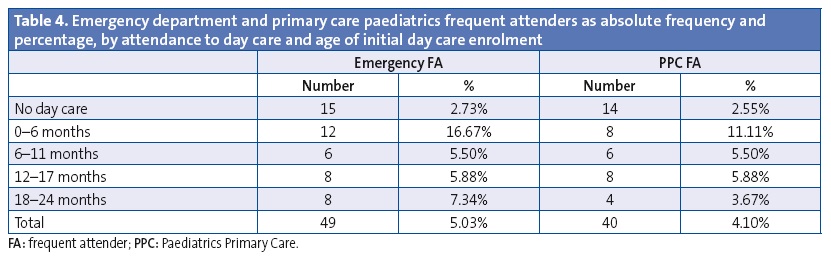

We defined FAs as children with a total number of visits in the two years under study that exceeded the mean plus two standard deviations (SDs). Emergency department FAs: the mean number of visits in the first two years of life was 2.69 with a SD of 2.99 (Table 3). Therefore, to be defined as FAs, children had to have made more than 8.67 visits in the first two years of life (5.03% of the total children under study) (Table 4).

Paediatrics primary care FAs: the mean number of visits in the first two years of life was 14.56 with a SD of 10.08 (Table 3). To be defined as FAs, children had to have made more than 34.72 visits in the first two years of life (4.10% of the total children in the study) (Table 4).

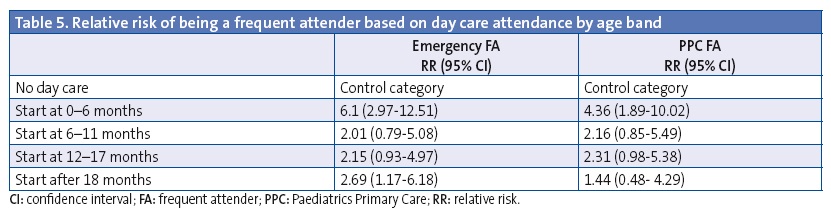

The group of children that started attending day care at earlier ages (between 0 and 6 months) had a higher percentage of FAs for both types of setting (Table 5), with a relative risk (RR) of frequent use of emergency services up to six times that of children that did not attend day care, and a RR of frequent use of PPC services that was four times that of children that did not attend day care.

Analysis of morbidity in children that were frequent attenders by number of episodes of disease

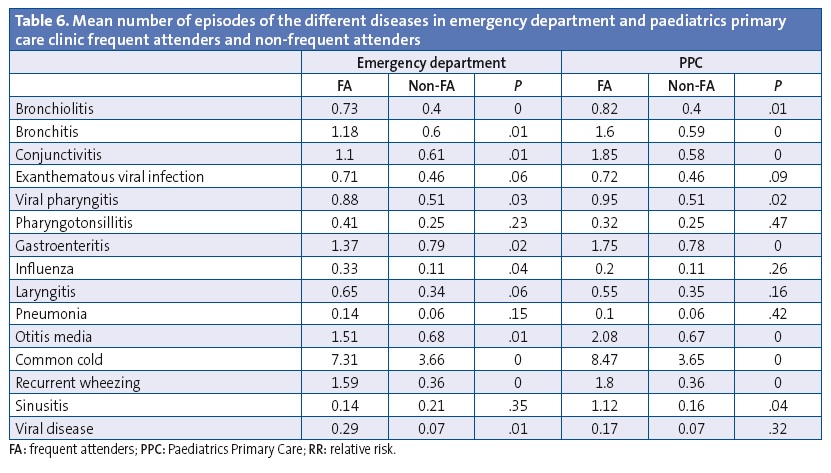

When we analysed the mean number of episodes of infectious disease in FAs compared to non-FAs, we found that most FAs did not only seek medical care more often, but also had a higher number of episodes of the most prevalent diseases under study (bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, gastroenteritis, otitis media, common cold, recurrent wheezing and sinusitis) (Table 6).

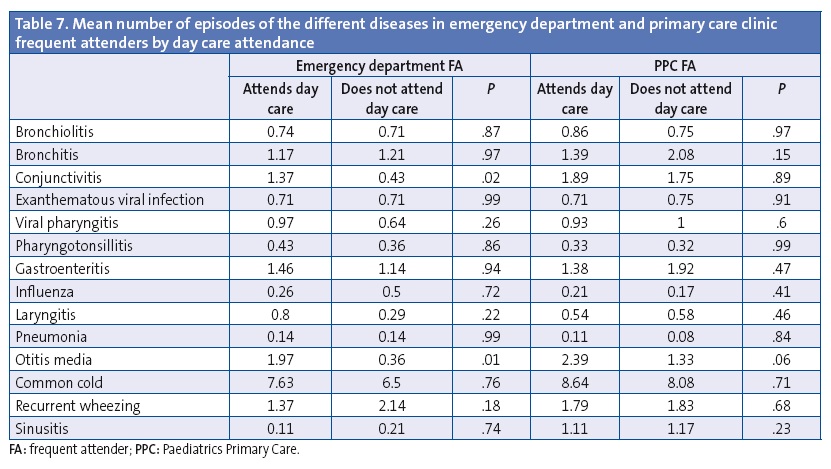

When we analysed the morbidity of FAs, we observed that day care attendance was not associated with statistically significant differences in morbidity (Table 7).

Study of medication use by frequent attenders

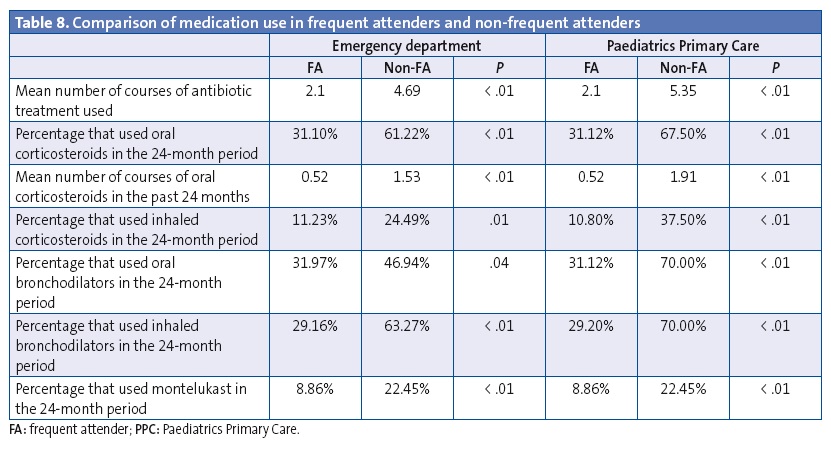

A higher percentage of FAs compared to non-FAs were treated with oral and inhaled bronchodilators, oral and inhaled corticosteroids, montelukast and antibiotics (P < .05) (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a prospective study designed by the research group of the Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics (Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria [AEPap])10 and adapted for the Autonomous Community of Asturias by the Association of Primary Care Paediatrics of Asturias (Asociación Asturiana de Pediatría de Atención Primaria [AAPap]): Infectious disease and health care resource use in children aged less than 2 years that attend day care centres.11 The universe of the study was the PPC clinics of the public health system that routinely serve between 90% and 95% of the paediatric population.12

The work was performed on a voluntary basis by 33 paediatricians and 20 nurses, which unquestionably improved data collection but did not allow for random sampling. The study was coordinated by the research group, which collected and reviewed the surveys before submitting them to the statistics team. The data were gathered during routine visits in an attempt to optimise the research capabilities of PPC teams.

The considerable number of paediatricians that participated allowed us to obtain a large sample, but also carried limitations, chief of which was the potential variability in diagnostic criteria. We tried to minimize this bias by predefining the diseases documented in the study.

Another limitation is that the study only took into account visits due to infectious diseases or episodes of recurrent wheezing, a potentially severe disease with a high prevalence in Asturias (45.6% of children experience at least one episode of wheezing in the first 36 months of life).12

Each episode that led to a health care visit and a specific diagnosis was documented only once, even if children made more than one visit in the context of a single disease process.

All visits to paediatric primary care and emergency services were documented, even if more than one visit was made for a single episode of disease.

We did not take into account the characteristics of day care centres or the time children spent in them, but in a study of similar characteristics, Lafuente et al13 did not find differences in morbidity based on the number of hours spent in day care or the staff-to-child ratio of the different centres.

Although the initial sample included 1139 children, the final sample consisted of 975 (73% of the total children born during the period and that received care in the health facilities under study).

Of the total population under study, 43.7% of children attended day care, a figure that approximated the one published in “Estadística de las enseñanzas no universitarias con 51,8 % de niños escolarizados a los dos años" (Statistics of pre-school, primary and secondary education, with 51.8% of children attending educational facilities by age two years).14

The mean number of visits to Paediatrics Services (emergency and primary care) per month was higher in children that attended day care and increased significantly when children started attending at an early age. These trends have also been observed in studies conducted in other autonomous communities in Spain.15,16

The development of the first episodes of infectious disease is displaced to earlier ages, when there is a greater risk of complications requiring medical attention.17

In our study, the mean number of visits per month to emergency or PPC services by age band (7 to 11 months, 12 to 18 months, and older than 18 months) increased after initial enrolment in day care (P = .000 in all categories). We must take into account that we could not analyse the group of infants aged less than 6 months because we did not have any data for the period preceding day care enrolment.

Although high-frequency use in paediatric age groups is a well-known phenomenon, few studies have been devoted to it.

Defining the number of visits required to categorise a patient as a FA is challenging, and we did not find consistent criteria in the medical literature we reviewed.

The Croatian National Institute of Health18 considered children to be FAs if the number of visits exceeded the 75th percentile (more than ten visits a year for a single child). In 2011, Melissa Klein et al set the cut-off point at more than two SD (nine or more visits in one year).19 Considering that these studies have been conducted in other countries and that the pattern of use of health care services may be influenced by a wide range of factors (personal factors in patients, sociodemographic factors, family or social support factors, and factors specifically related to the health care system [paediatric services versus general medicine at the primary care level, availability and accessibility]), the results of other studies can be used for guidance, but not for comparison.

Studies conducted in Spain have found a prevalence of frequent attendance, defined as the mean plus one SD, of 14.89%, but the age range under study was 0 to 14 years and the duration of followup three months.20 If we apply the same definition to another study conducted in 2012 in the primary care setting with a followup of 12 months, the data show that in children aged less than 1 year, FAs would be those that made more than nine visits a year, and in children aged 1 to 2 years, children that made more than 12 visits. The overall percentage of FAs would be 11.86%.21 This study took into account all on-demand appointments and had a significantly smaller sample than our study.

In our study, which analysed visits to emergency services and to PPC clinics separately and had a followup period of two years, FAs in paediatric services corresponded to children that made more than 34.72 visits in the two-year period.

The only factor under study for which we found a significant association with frequent use of services was day care attendance, and this association was stronger in children that started attending day care before age 6 months (RR FA use, 6 for the emergency department and 4.36 for PPC clinics). There are previous studies that support this association.17

All of the above results in an increased use of health care resources by children that attend day-care centres, not only due to the number of parental work-loss days,22 but also to the increased use of antibiotics,13,23,24 as up to 80% of visits by infants aged up to 12 months resulted in antibiotic treatment.25

We found that the RR of using medication (antibiotics, oral and inhaled bronchodilators, oral and inhaled corticosteroids or montelukast) was higher in children that started attending day care earlier. When we analysed FAs separately (regardless of whether they did or did not attend day care) we found an overall higher use of medication (P < .05).

The term “frequent attender” usually carries negative connotations, so we also set out to determine whether this term could be misleadingly applied to a subset of the children that we serve that have a high-risk immunologic profile (a predisposing factor) and in whom this scheme of care (day care) could act as a trigger, given that day care attendance is associated with an increased incidence of these diseases as well as recurrent wheezing.

Although the total number of FAs in our study was small—which is explained by the fact that the study was not originally designed to analyse this variable—we compared the number and type of infectious diseases in FAs that attend day care versus FAs that do not, and found no statistically significant differences. Therefore, FAs, whether they attend day care or not, are children that on average experience a significantly higher number of episodes of nearly every infectious disease analysed in the study and of recurrent wheezing. This also seems to support the hypothesis of children that are FAs having a specific immunologic profile.

CONCLUSIONS

- Day care attendance is associated with a higher probability of frequent health care use (of emergency departments or PPC clinics).

- Children that were FAs had respiratory and infectious diseases more frequently, and this increased incidence was accounted for by day care attendance.

- This increased incidence of disease probably results in an increased use of medication (antibiotics, oral and inhaled bronchodilators, oral and inhaled corticosteroids and montelukast).

- The increased incidence of respiratory and infectious disease in all FA use groups suggests that these could be subject to further research.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

This study has been funded by the Office Health Biology Research of the Principality of Asturias, record number AP10-11, ruling of June 2010. The study received no other funding.

ABBREVIATIONS: AAPap: Asociación Asturiana de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Primary Care Paediatrics Association of Asturias)· AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics)· CI: confidence interval · FA: frequent attender · PC: primary care · PPC: Paediatrics Primary Care · RR: relative risk · SD: standard deviation · SESPA: Servicio Público de Salud del Principado de Asturias (Public Health Service of the Principality of Asturias) · WHO: World Health Organization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful for the support received from the Statistical Consulting Unit of the Scientific and Tehcnical Services of the Universidad de Oviedo, and especially from Tania Iglesias Cabo.

MORBIGUARD research group: Aide Aladro Antuna, Ana María Pérez López, Begoña Domínguez Aurrecoechea, Encarnación Díez Estrada, Francisco J. Fernández López, José I. Pérez Candas, Leonor Merino Ramos, María Fernández Francés, María Ángeles Ordóñez Alonso, Purificación López Vilar, Sonia Ballesteros García, Mar Coto Fuente. Collaborating group: Isabel González-Posada Gómez, Sonia Alonso Álvarez, María Agustina Alonso Álvarez, Diana Solís, Josefina Collao Alonso, Margot Morán Gutiérrez, Ángel Costales-Gloria Peláez, Mónica Cudeiro Álvarez, Beatriz Fernández López, María Pilar Flórez Rodríguez, Cruz Andrés Álvarez, Isolina Patallo Arias, Mónica Fernández Inestal, Ana Pérez Vaquero, Carmen Díaz Fernández, Silvia Ruisánchez Díez, Antonia Sordo, María Antonia Castillo, Lidia González Guerra, Águeda García Merino, Teresa García, María Teresa Canon del Cueto, Laura Tascón Delgado, Isabel Tamargo Fernández, Laura Lagunilla Herrero, Susana Concepción Polo Mellado, Cruz Bustamante Perlado, Susana Parrondo, Nevada Juanes Cuervo, Ana Arranz Velasco, Belén Aguirrezabalaga González, Mario Gutiérrez Fernández, Isabel Mora Gandarillas, Rosa María Rodríguez Posada, Isabel Fernández Álvarez-Cascos, Isabel Carballo Castillo, Felipe González Rodríguez, Tatiana Álvarez González, Zoa Albina García Amorín, Monserrat Fernández Revilla, Fernando Nuno Martín.

REFERENCES

- La asistencia al niño en las guarderías y residencias infantiles. Informe técnico n.º 256. In: Organización Mundial de la Salud [online] [consulted on 14/09/2016]. Available in http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37485

- Encuesta de población activa. Módulo de conciliación entre la vida laboral y familiar. In: Instituto Nacional de Estadística [online] [consulted on 14/09/2016]. Available in www.ine.es/prensa/np417.pdf

- Enserink R, Ypma R, Donker GA, Smit HA, Van Pelt W. Infectious disease burden related to child day care in the Netherlands. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e334-40.

- Ochoa Sangrador C, Barajas Sánchez MV, Muñoz Martín B. Relación entre la asistencia a guarderías y enfermedades infecciosas agudas en la infancia. Una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2007;81:113-29.

- Thrane N, Olesen C, Md JT, Søndergaard C, Schønheyder HC, Sørensen HT. Influence of day care attendance on the use of systemic antibiotics in 0 to 2 years old children. Pediatrics. 2001:107;e76.

- Marshall BC, Adler SP. The frequency of pregnancy and exposure to cytomegalovirus infections among women with a young child in day care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:163.e1-5.

- Hedin K, Andre M, Mölstad S, Rodhe N, Petersson C. Infections in families with small childrIn: use of social insurance and healthcare. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24:98-103.

- Oterino de la Fuente D, Peiró Moreno S. Utilización de los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios por niños menores de dos años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2003;58:23-8.

- Janicke DM., Finney JW, Riley AW. Children’s health care use. A prospective investigation of factors related to care-seeking. Med Care. 2001;39:990-1001.

- Del Castillo Aguas G, Gallego Iborra A, Ledesma Albarrán JM, Gutiérrez Olid M, Moreno Muñoz G, Sánchez Tallón R. Influencia de la asistencia a las guarderías sobre la morbilidad y el consumo de recursos sanitarios en niños menores de dos años. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2009;11:695-708.

- Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Fernández Francés M, Ordóñez Alonso MA, López Vilar P, Pérez Candás JI, Merino Ramos L, et al. Patología infecciosa y consumo de recursos sanitarios en menores de 2 años que acuden a guarderías. An Pediatr (Barc). 2015;83:149-59.

- Actividad ordinaria en centros de Atención Primaria Informe resumen evolutivo del sistema nacional de salud 2007-2009. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad [online] [consulted on 14/09/2016]. Available in http://goo.gl/iKebiP

- Cano Garcinuño A, Mora Gandarillas I, Grupo SLAM. Patrones de evolución temporal de las sibilancias en el lactante. Bol Pediatr. 2012;52:86-7.

- Lafuente Mesanza P, Lizarraga Azparren MA, Ojembarrena Martínez E, Gorostiza Garay E, Hernaiz Barandiarán JR. Escolarización precoz e incidencia de enfermedades infecciosas en niños menores de 3 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2008;68:30-8.

- Estadística de las enseñanzas no universitarias. Curso 2012-2013. In: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Subdirección General de Estadística y Estudios [online] [consulted on 14/09/2016]. Available in http://goo.gl/i3ioPx

- Gorrotxategi Gorrotxategi P, Aseguinolaza Iparraguirre I, Sarrionandia Uribelarrea MJ, di Michele Russo A, Reguilón Miguel MJ, Caracho Arbaiza MR, et al.La asistencia a la guardería aumenta no solo la morbilidad, sino también el uso de recursos sanitarios. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2013;15:177-9.

- Enserink R, Ypma R, Donker G A, Smit HA, van Pelt W. Infectious disease burden related to child day care in the Netherlands. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e334-40.

- Stojanović-Špehar S, Blažeković-Milaković S, Bergman-Marković B, Matijašević I. Preschool children as frequent attenders in Primary Health Care in Croatia: retrospective study. Croat Med J. 2007;48:852-9.

- Klein M, Vaughn LM, Baker RC, Taylor T. Welcome back? Frequent attenders to a pediatric primary care center. J Child Health Care. 2011;15:175-86.

- Tapia Collados C, Gil Guillén V, Orozco Beltrán D, Bernáldez Torralba C, Ortuño Adán E. Hiperfrecuentación en las consultas de Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria.2004:6:547-57.

- Parrilla Roure M, Palma Barrio RM, Bailón López RM, Fanego Fernández A, Santisteban Robles M. Hiperfrecuentación pediátrica en dos centros de salud urbanos. Comunicación oral. Congreso SEPEAP 2013. In: Pediatría en Atención Primaria [online] [consulted on 14/09/2016]. Available in http://goo.gl/U0eQir

- Churchil R, Pickering L. Infection control challenges in child-care center. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;2:347-63.

- Nordlie AL, Andersen BM. Changes in antibiotic consumption among day-care children in Oslo. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:2924-6.

- Thrane N, Olesen C, Søndergaard C, Schønheyder HC, Sørensen HT. Influence of day care attendance on the use of systemic antibiotics in 0- to 2-year-old children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e76.

- Nordlie AL, Andersen BM. Children in day care centers: infections and use of antibiotics. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122:2707-10.