Vol. 27 - Num. 107

Originales

Promoción de la salud comunitaria mediante la implementación del programa “Cuidando la salud de tu hijo”

Ana Martín Gerechtera, Marta Esther Vázquez Fernándeza

aPediatra. CS Circunvalación. Gerencia de Atención Primaria de Valladolid Este. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

Correspondencia: A Martín. Correo electrónico: a.martingere@gmail.com

Cómo citar este artículo: Martín Gerechter A, Vázquez Fernández ME. Promoción de la salud comunitaria mediante la implementación del programa “Cuidando la salud de tu hijo” . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:245-57. https://doi.org/10.60147/6fbb2c2e

Publicado en Internet: 03-09-2025 - Número de visitas: 5111

Resumen

Ante la necesidad de varias familias de resolver dudas sobre la crianza y temas relacionados con la salud de sus hijos, ha surgido la iniciativa por parte de un equipo de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de desarrollar esta actividad comunitaria. Se trata de cuatro talleres en los que se ofrece formación en prevención e identificación de enfermedades infantiles, conocimientos sobre desarrollo neurológico, alimentación, infecciones y uso de pantallas, así como habilidades para actuar en situaciones urgentes. En definitiva, espacios donde se resuelven inquietudes y se teje una red de apoyo social, principalmente en familias primerizas. El estudio evidencia la importancia de la prevención y promoción de la salud, mostrando que el aprendizaje tras estas actividades es posible y necesario, mejora la relación familiar con los sanitarios, fomenta hábitos saludables y aumenta el conocimiento en salud pediátrica en el hogar.

Palabras clave

● Formación ● Prevención ● Promoción ● Salud ● TalleresINTRODUCCIÓN

La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) recuerda que la educación para la salud es una estrategia para mejorar los resultados en salud y reducir las inequidades1. Diversos estudios han demostrado que dicha educación contribuye a mejorar el manejo de enfermedades comunes y reduce la sobrecarga en los servicios de salud2. Estas iniciativas permiten acercar el conocimiento a la población, fomentando hábitos de vida más saludables y dotando a las familias, especialmente a las más desfavorecidas desde el punto de vista de los determinantes sociales de la salud (DSS)3, de herramientas y habilidades para el autocuidado. Buscan no solo informar, sino capacitar y “alfabetizar en salud”4,5.

En este contexto, hemos desarrollado un proyecto denominado “Cuidando la salud de tu hijo/a”, dirigido especialmente a las gestantes y familias durante los primeros tres años de vida. Los temas abordados (cuidados del niño/a, hitos del desarrollo, lesiones habituales de la piel, alimentación, prevención de la obesidad, uso precoz y excesivo de pantallas, fiebre e infecciones respiratorias y primeros auxilios) responden a las inquietudes más frecuentes de los cuidadores en los primeros años de la vida6. Los objetivos específicos son:

- Conseguir que las familias resuelvan dudas que se plantean durante la crianza.

- Describir y realizar las actividades que incluye esta actividad comunitaria.

- Valorar factores epidemiológicos y socioculturales que influyen en el interés de esta actividad por parte de la población.

- Conocer el nivel de satisfacción global de las familias que realizan la actividad.

- Evaluar la efectividad de la promoción de la salud mediante el análisis de conocimientos antes y después de la asistencia.

- Analizar la experiencia adquirida y crear un modelo exportable a otras áreas de salud.

MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS

Población a la que se dirige

- Criterios de inclusión: gestantes y familias con hijos menores de 3 años de vida de la provincia de Valladolid.

- Criterios de exclusión: falta de comprensión del idioma español, salvo presencia de traductor.

Captación de participantes

Se realizó difusión desde las consultas de enfermería, matronas y pediatras de las dos Áreas de Salud de Valladolid, durante controles prenatales y revisiones infantiles en el centro de salud. Se publicitó mediante cartelería en centros de salud y centros cívicos, redes sociales (RRSS) institucionales (Sanidad de Castilla y León [Sacyl], Asociación de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de Castilla y León [APAPCYL], Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria [AEPap]) y medios de comunicación (prensa, radio y TV local).

Población estudiada

Las familias informadas rellenaban un formulario vía código QR. En él se recogía la inscripción, el consentimiento informado y si acudirían acompañados. Se permitieron entre 25-30 personas por taller. Si se completaba se les ofrecía la siguiente edición.

Equipo motor y personal que los dinamiza

Tras la elaboración de las actividades y el diseño del estudio por el equipo motor6, formado por pediatras, se constituyó un equipo de trabajo multidisciplinar para dinamizar los talleres: enfermería pediátrica, pediatras, médicos de familia y comunitaria, médicos y enfermeros internos residentes (MIR, EIR) de pediatría, estudiantes de enfermería y de medicina. En cada taller participaba un educador y un observador; que recogía datos de asistencia y participaba en las dinámicas de grupo.

Ámbito y tiempo de realización

La actividad se realizó en los centros cívicos de cada Área de Salud, abarcando así a toda la provincia de Valladolid; según la Agencia Tributaria, la diferencia económica entre las dos Áreas7,8 supone una diferencia de recursos de un 47,07%, según la diferencia porcentual del valor medio del rendimiento neto del trabajo.

La periodicidad fue de un taller por semana de forma alternante en cada Área. Se realizaron desde mayo de 2024 a marzo de 2025, en horario de tarde de 17:30 a 19:00 horas.

Magnitud alcanzada

La actividad ha sido validada por el Ministerio de Sanidad como activo en salud y está incluida en el mapa de recursos de LOCALIZA SALUD. El proyecto se inició primero en un Área de Salud y luego en la otra. Además, se está empezando a impartir en población con riesgo de vulnerabilidad (marroquíes, con el apoyo de una traductora y cuestionarios traducidos al árabe, en etnia gitana y en una guardería pública).

Intervención educativa

La actividad consistía en la impartición de cuatro talleres:

- Taller de cuidados generales: ¿Es normal lo que le pasa a mi hijo/a?

- Taller de alimentación y prevención de la obesidad infantil.

- Taller de fiebre e infecciones respiratorias.

- Taller de primeros auxilios ante situaciones urgentes.

Las dinámicas de los talleres (Tabla 1) han sido diseñadas con metodología proCC (procesos correctores comunitarios) y de educación para la salud (EPS) grupal participativa basada en pedagogía activa9. Al finalizar cada taller se respondían las dudas y se afianzaban los conocimientos, compartiendo lo que más les había gustado o aprendido.

| Tabla 1. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': estructura de los talleres impartidos (contenido, técnica y duración) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Taller 1. Cuidados generales | Técnica | Tiempo (minutos) |

| 1. Presentación del taller y del contrato formativo | Tormenta de ideas. Rellenan QR formulario conocimientos anteriores | 5 |

| 2. Expectativas y miedos sobre paternidad/maternidad | Lluvia de ideas (app Mentimeter) | 10 |

| 3. ¿Cuáles son los cuidados básicos del recién nacido? | Phillips 66/Expositiva | 10 |

| 4. Qué es normal y qué no es normal | Se muestran fotografías. Con tarjetas de colores, las familias evalúan la gravedad. Discusión | 20 |

| 5. Desarrollo neurológico: signos de alerta | Investigación en el aula. Hitos del desarrollo, qué nos debe alarmar. Impacto de la tecnología en menores. Respuesta comentada | 20 |

| 6. Recursos digitales recomendados | Se exponen dudas, preguntas | 15 |

| 7. Evaluación | Ronda de evaluación. Encuesta satisfacción. Formulario conocimientos posteriores al taller | 10 |

| Taller 2. Alimentación y prevención obesidad infantil | Técnica | Tiempo (minutos) |

| 1. Presentación del taller y del contrato formativo | Dinámica de presentación. Tormenta de ideas. Formulario conocimientos anteriores | 5 |

| Expositiva | ||

| 2. Alimentación saludable/no saludable. “¿Qué comisteis ayer?” | Debate | 15 |

| 3. Ventajas y desventajas de una alimentación saludable | Rejilla | 10 |

| 4. Lectura de etiquetas y compra saludable | Práctica y vídeo “Comida económica y saludable” | 15 |

| 5. Juego de preguntas y respuestas | Concurso de preguntas online (Kahoot) | 15 |

| 6. Sedentarismo y pantallas digitales | Lluvia de ideas. Habilidades control parental | 20 |

| 7. Evaluación | Rueda/Encuesta satisfacción. Formulario conocimientos posteriores al taller | 10 |

| Taller 3. Fiebre e infecciones respiratorias | Técnica | Tiempo (minutos) |

| 1. Presentación del taller y del contrato formativo | Tormenta de ideas. Formulario conocimientos anteriores | 5 |

| Expositiva. Distinción infección respiratorias altas: vírico/bacteriano; gripe/faringoamigdalitis/otitis… | ||

| 2. Experiencias respecto a niños/as con fiebre. ¿Qué sintieron? ¿Qué hicieron? ¿Surgió algún problema? | Tormenta de ideas | 10 |

| 3. Quiniela y decálogo de la fiebre y la tos26 | Investigación/Analítica. Se reparten cuadrantes con situaciones y soluciones posibles (verdadero/falso/no sé) se di en pequeños grupos | 20 |

| 4. Casos prácticos: ¿Qué hacer ante…? | Habilidades | 30 |

| Expositiva | ||

| 5. Lavados nasales y toma de temperatura | Vídeo lavados nasales | 20 |

| Rol Playing | ||

| 6. Evaluación (actividad 7) | Rueda/Encuesta de satisfacción y formulario conocimientos posteriores al taller | 5 |

| Taller 4. Primeros auxilios | Técnica | Tiempo (minutos) |

| 1. Presentación del taller y del contrato formativo | Tormenta de ideas. Formulario conocimientos anteriores | 5 |

| 2. Teoría de primeros auxilios ante situaciones urgentes | Expositiva | 25 |

| 3. Práctica | Habilidades. Trabajo en pequeños grupos con simuladores. Atragantamiento, posición de seguridad, RCP adulta e infantil, crisis convulsiva, asmática y diabética27 | 50 |

| 4. Evaluación (actividad 4) | Rueda/Encuesta satisfacción. Formulario conocimientos posteriores al taller | 10 |

Cálculo del tamaño muestral necesario

El tamaño muestral se realizó con la calculadora GRANMO versión 7.12 para una estimación de una proporción en población. Se necesitaban al menos 61 sujetos (se consideró un nivel de confianza del 95%, alfa 0,05, un poder >0,8, contraste bilateral), asumiendo mejora del 0,7 al 0,9%.

Diseño del estudio

Estudio observacional analítico prospectivo basado en la experiencia adquirida tras la implementación del programa “Cuidando la salud de tu hijo/a”.

Variables para estudiar

Se recogieron datos anónimos de asistencia y epidemiológicos de los asistentes (sexo, edad, número de hijos/as, nivel de estudios) y formularios de conocimientos y satisfacción de elaboración propia e independientes para cada taller. El mismo formulario de conocimientos fue respondido antes y después del taller (Tabla 2). La hipótesis analizada era si se había producido un aprendizaje significativo tras los talleres.

| Tabla 2. Preguntas y porcentaje de aciertos antes y después de la formación | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preguntas sobre cuidados generales (Verdadero/Falso/No sé) | Aciertos (%) | |

| Antes | Después | |

| El cuidado del recién nacido y del bebé es fundamentalmente de la madre | 90,6% | 96% |

| El ombligo se debe curar con alcohol | 100% | 96% |

| Si el bebé llora antes de 3 horas es porque no se tiene leche suficiente | 93,8% | 96% |

| Hay que organizar cuanto antes el horario de las tomas para que el bebé se regule y aprenda | 61,1% | 78,6% |

| Durante la lactancia no es posible quedarse embarazada | 100% | 100% |

| Untar el chupete en miel o azúcar le ayuda a tranquilizarse | 94,4% | 100% |

| Si se tiene una mastitis (inflamación de la glándula mamaria) se debe suspender la lactancia | 78,1% | 92% |

| No se puede tomar ningún medicamento dando el pecho | 96,9% | 100% |

| La mayoría de las erupciones de la piel en la niñez son benignas y suelen desaparecer por sí solas | 77,8% | 87,5% |

| El desarrollo neurológico es completo desde el nacimiento | 85,7% | 100% |

| Si el menor no balbucea a los 6 meses o no contesta con sonidos cuando le hablas me debo preocupar | 71,4% | 38,5% |

| ¿Cuándo es normal que el bebé se mantenga sentado? Antes de los 6 meses/De los 6 a los 9 meses/Después de los 9 meses |

100% | 100% |

| El uso de pantallas produce retraso del lenguaje y aumenta los síntomas del déficit de atención e hiperactividad | 100% | 100% |

| ¿Hasta qué edad crees que tu hijo no debe hacer uso de pantallas (TV, móviles, tablet)? Antes de los 2 años/Antes de los 6 años/Antes de los 12 años/No lo sé |

7,1% | 30,8% |

| Preguntas sobre alimentación (Verdadero/Falso) | Aciertos (%) | |

| Antes | Después | |

| Los conceptos de alimentación y nutrición son lo mismo | 86,5% | 96,3% |

| Los niños/as deben comer cuando les apetezca, sin horarios regulares | 62,2% | 85,2% |

| Comer con la televisión, tablet o smartphone encendidos ayuda a conseguir que coman todo y más rápido | 91,9% | 96,2% |

| Las dietas vegetarianas tienen más riesgo de anemia por carencia de hierro | 40,5% | 48,2% |

| No se debe comer ningún tipo de grasas. Son perjudiciales para la salud | 91,9% | 100% |

| El etiquetado nos ayudará en la elección de alimentos saludables | 86,5% | 96,3% |

| Los alimentos procesados y ultraprocesados son lo mismo | 89,2% | 85,2% |

| La realización de algún ejercicio físico mejora la salud actual y futura | 97,3% | 100% |

| Preguntas sobre la fiebre/infecciones respiratorias (Verdadero/Falso/No sé) | Aciertos (%) | |

| Antes | Después | |

| La cantidad de fiebre nos orienta sobre la gravedad de la infección | 19,1% | 75,6% |

| Hay que dar ibuprofeno o paracetamol siempre que el menor tenga fiebre | 64,3% | 82,9% |

| En algunos niños/as predispuestos, la fiebre puede desencadenar convulsiones | 85,5% | 95,1% |

| Hay que intentar bajar la temperatura con friegas de alcohol y baños en agua fría | 57,1% | 87,8% |

| Los catarros no producen fiebre | 45,2% | 41,5% |

| Cualquier infección respiratoria puede ser grave y necesita ser vista pronto por un médico | 34,2% | 82,9% |

| La tos ayuda a eliminar el moco de las vías respiratorias | 73,17% | 100% |

| Hay medicamentos eficaces para tos y mocos para todas las edades | 33,3% | 78,1% |

| Las infecciones respiratorias se curan más rápido con antibiótico | 52,5% | 90,2% |

| Preguntas sobre primeros auxilios y situaciones emergentes | Aciertos (%) | |

| Antes | Después | |

| ¿Considera importante una formación en primeros auxilios? | 100% | 100% |

| ¿Ha visto alguna vez una situación donde fue necesario aplicar primeros auxilios? Respuesta: Sí |

35,62% | 100% |

| Conducta PAS significa: Peligro, ayuda, salvar / Proteger, avisar, socorrer / Peligro, avisar, salvar / No lo sé |

87,67% | 100% |

| ¿Conoces la posición de seguridad y cómo realizarla? Respuesta: Sí |

64,38% | 100% |

| ¿Cómo reconocería si una persona inconsciente está respirando o no? Observando si su pecho sube y baja/Simplemente escuchando/Viendo, oyendo y sintiendo si respira |

87,93% | 93,75% |

| Si una persona permanece en el suelo inmóvil tras una caída repentina, ¿qué debemos hacer si no responde a estímulos, pero respira bien? Intentar levantarlo o sentarlo para ver si responde a los estímulos/Ponerlo boca arriba para que respire mejor/Ponerlo en posición lateral de seguridad, llamar a la ambulancia y comprobar que sigue respirando/Realizarle el masaje cardiaco |

100% | 100% |

| ¿Cuántas presiones e insuflaciones hay que dar a una persona en parada cardiorrespiratoria en un adulto? 15 compresiones y 2 insuflaciones/30 compresiones y 2 insuflaciones/30 compresiones |

64,81% | 100% |

| Cuando una persona se ha atragantado y está tosiendo es recomendable: Darle palpadas en la espalda/Intentar sacar el objeto con nuestros dedos/Animarle a que tosa con fuerza, pero sin hacer ninguna de las acciones anteriores |

80,82% | 95,56% |

| ¿Qué harías en el caso de que una persona atragantada pierda el conocimiento? Dar palpadas en la espalda/Iniciar la maniobra de reanimación cardiopulmonar/Practicar la maniobra de Heimlich |

53,06% | 71,43% |

| Ante una persona que presenta una reacción alérgica anafiláctica se debe administrar adrenalina. Solo deben administrarla los servicios sanitarios | 47,95% | 91,30% |

| Los diabéticos que reciben tratamiento con insulina pueden comer cualquier tipo de alimento | 73,97% | 71,11% |

Se incluyeron 42 preguntas: 14 preguntas del primer taller, 8 del segundo, 9 del tercero y 11 del cuarto. Así como 5 preguntas sobre el contenido, la utilidad, la estructura del taller y una pregunta abierta para los temas que más les interesaron y sugerencias.

Análisis estadístico

Para la recogida de datos se confeccionó una base de datos en Excel. Se calcularon medias con intervalos de confianza (IC), desviaciones estándar de la media (DE), la mediana (IC), rangos, error típico, coeficiente de variación (CV) y frecuencias de los resultados del pre y post test.

Se ha utilizado Excel Microsoft 365 y la ayuda de la inteligencia artificial (ChatGPT). Las comparaciones de medias para el porcentaje de aciertos se han calculado con la prueba T de Student para muestras independientes y normalidad de datos; y la comparación de las varianzas, con la prueba F de Snedecor. Se consideraron estadísticamente significativos los valores por debajo de 0,05.

Este estudio fue aprobado por el Comité de Ética de Investigación Clínica de las Área de Salud correspondiente y apoyado por la Unidad de Apoyo a la Investigación del Área Este de Valladolid.

RESULTADOS

Asistencia

Se han realizado cuatro ediciones en un Área de Salud y dos en la otra. Este estudio recoge las dos últimas ediciones de cada Área de Salud. Se registraron un total de 184 personas de forma voluntaria e informadas (Tabla 3), superando las previsiones del cálculo inicial. El promedio de cada taller ha sido de 12,27 personas (DE 5,67 personas). Globalmente, las mujeres acudieron más que los varones (71,73%, IC [71,45; 72]). Hasta en un 80% se trataba de parejas.

| Tabla 3. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': representación numérica de participantes en el estudio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taller | Media de personas asistencia por taller | Área | Mes | Personas por mes y taller |

| T1 | 10,67 | ESTE | Octubre | 7 |

| Enero | 11 | |||

| OESTE | Octubre | - | ||

| Enero | 14 | |||

| T2 | 9,25 | ESTE | Octubre | 4 |

| Enero | 5 | |||

| OESTE | Octubre | 10 | ||

| Enero | 18 | |||

| T3 | 10,5 | ESTE | Octubre | 5 |

| Marzo | 10 | |||

| OESTE | Octubre | 15 | ||

| Marzo | 12 | |||

| T4 | 18,25 | ESTE | Octubre | 14 |

| Marzo | 20 | |||

| OESTE | Octubre | 23 | ||

| Marzo | 16 | |||

| Total de asistentes/respuestas recogidas | 184 | |||

| Media total | 12,27 (DE 5,66) | |||

Más del 80% de los asistentes eran primerizos y tenían más de 30 años. Apenas se observan diferencias en género y edad entre las dos Áreas. En cuanto al nivel de estudios, en el Área Este, el 6,58% tenían estudios básicos, 28,95% de formación profesional y 64,47% universitarios; frente al 2,7% de estudios básicos, 24% de formación profesional y 72,2% universitarios del Área Oeste. (Tablas 4 y 5).

| Tabla 4. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': datos demográficos por Áreas (leve porcentaje distinto: ausencia de respuesta participante) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESTE | OESTE | ||||||

| Género | Edad | Estudios | N.º hijos | Género | Edad | Estudios | N.º hijos |

| Mujeres | Entre 20-30 años | Básico | 1 hijo | Mujeres | Entre 20-30 años | Básico | 1 hijo |

| 70,83% | 11,84% | 6,58% | 88,16% | 73,15% | 11,11% | 2,78% | 80,56% |

| Hombres | Más de 30 años | Formación profesional (módulo) | 2 o más hijos | Hombres | Más de 30 años | Formación profesional (módulo) | 2 o más hijos |

| 31,94% | 88,16% | 28,95% | 9,21% | 26,85% | 87,96% | 24,07% | 12,04% |

| Universitario | Universitario | ||||||

| 64,47% | 72,22% | ||||||

| Tabla 5. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': datos demográficos totales | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TODO | ||||

| Género | Edad | Estudios | N.º Hijos | |

| Mujeres | Entre 20-30 años | Básico | 1 hijo | |

| 71,74% | 11,41% | 4,35% | 83,70% | |

| Hombres | Más de 30 años | Formación profesional (módulo) | 2 hijos | |

| 28,26% | 88,04% | 26,09% | 10,87% | |

| Universitario | ||||

| 69,02% | ||||

Conocimientos previos y posteriores

Pese a que hubo mejora de algunas preguntas y otras no se modificaron, en general todos los talleres han demostrado mejora de conocimientos en los participantes (Tabla 6).

| Tabla 6. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': porcentaje de aciertos | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tabla porcentaje de aciertos | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

| Antes | 82,64% | 80,74% | 51,26% | 69,62% |

| Después | 86,81% | 88,41% | 81,57% | 92,32% |

| Diferencia (% de mejoría) | 4,166% | 7,666% | 30,308% | 22,694% |

Los que menos mejoraron fueron el primer taller de cuidados generales, seguido del de alimentación. El que mostró mayor mejoría fue el taller sobre infecciones respiratorias: se acertó un 51,26% IC (37,08 a 55,4) del total de preguntas, y tras la formación, un 81,57% IC (69,83 a 93,3). Esto supone una diferencia de un 30,30%. El segundo fue el taller sobre primeros auxilios, donde se pasó de 69,2% IC (52,7 a 82,15) de aciertos a un 92,32% IC (85,17 a 99,45) al recibir la formación.

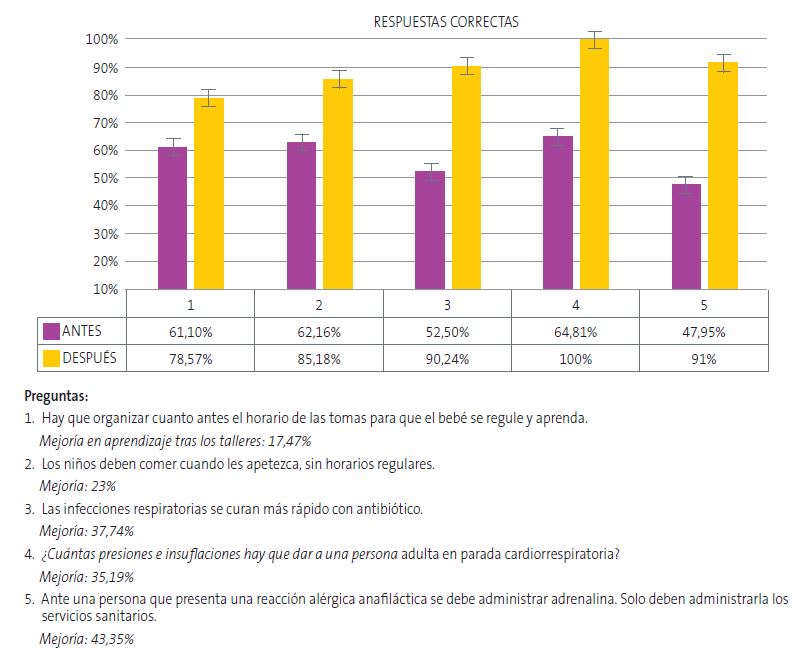

De forma global, los talleres han demostrado una diferencia de conocimientos significativa de un 16,2% (p <0,05). En la Figura 1 se muestran las preguntas más relevantes en cuanto a mejora de resultados.

Análisis de conocimientos por Áreas de Salud

En el Área Este, se aprecia un porcentaje de mejora entre las preguntas antes y después de un 16,10% IC (6,2 a 26). El tercer taller de fiebre e infecciones respiratorias ha sido el que más ha generado diferencia, con un 27,89%. En el Área Oeste, hay un porcentaje de mejora del 15,22% IC (1,28 a 29,5), destacando el taller de primeros auxilios, en el que las respuestas mejoraron un 26,98% frente a las del Este, con 11,50%. En general, las diferencias entre el Área Este y Oeste fueron discretas y, por tanto, no significativas.

Respecto a los conocimientos previos, de forma global, el Área Oeste presentaba más conocimientos previos respecto al Área Este (5,28%). El porcentaje de aciertos tras los talleres en el Área Oeste fue mayor en los tres primeros talleres, superando el 10%. Solo en el de primeros auxilios el Área Este demostró tener más conocimientos previos.

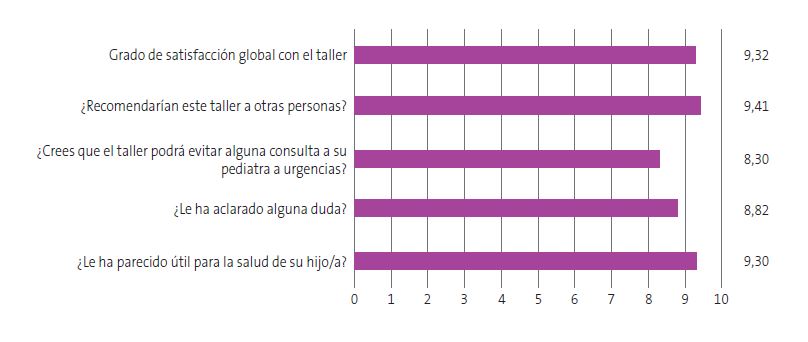

Cuestionario de satisfacción

Los asistentes evaluaron los talleres con una media de satisfacción global de 9 sobre 10, con un IC de 95% (8,91 a 9,14) y una baja dispersión (DE 1,57) (Figura 2). El taller que menos respuestas positivas ha tenido ha sido el de alimentación y obesidad, con una media de valoración de 8,16 (DE 2,16). Y el que más, el de fiebre e infecciones. No se observan diferencias significativas entre los distintos talleres.

| Figura 2. 'Cuidando la salud de tu hijo': grado de satisfacción de los participantes (media de respuestas sobre 10) |

|---|

|

La pregunta abierta reveló el interés por profundizar en lactancia, recibir presentaciones, dar continuidad a la actividad y hacer algunas sesiones online.

Resultados e impacto comunitario

El proyecto se publicó en medios de comunicación y RRSS locales10-14, incluyendo la Asociación de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de Castilla y León15.

DISCUSIÓN

Pese a las limitaciones que pueden tener este tipo de estudios y que detallamos al final de la discusión, son muchas las actividades comunitarias16 en Atención Primaria que han demostrado ser una estrategia efectiva para la promoción de estilos de vida saludable y prevención de las enfermedades. Un estudio publicado en nuestra zona de salud en el año 2020 titulado Si es urgente para ti, ¿es urgente para mí?17 demuestra que los programas de alfabetización en salud realizados con familias disminuyen las consultas pediátricas y mejoran su adecuación comparada con un grupo control de familias que no los realizan.

Este estudio, Cuidando la salud de tu hijo/a, también ha evaluado la efectividad de esta actividad comunitaria dirigida a las familias para que se modifiquen hábitos y estilos de vida, que desde el momento preconcepcional y la primera infancia pueden influir en su salud y en su vida adulta. De forma global, se ha observado una mejoría de más de un 16% en los conocimientos (p <0,005); en cuanto a las preguntas erróneas, el 75,8% pasaron a ser correctas tras la formación. Esto indica que tras los talleres han podido ampliar y mejorar los conocimientos con los que partían. Además, quitando las preguntas que no han tenido mejora (por ser muy obvias), o mejora “negativa” (sesgo de falta de adhesión y compromiso del participante al responder), se mejora en más de un 20%.

El taller de primeros auxilios despertó el mayor interés y asistencia, mientras que el de fiebre e infecciones respiratorias logró la mayor mejora de conocimientos. Es alentador que la mayoría aprendiera a seguir un algoritmo de emergencia, contactar con servicios de salud y actuar en reanimación cardiopulmonar (RCP), atragantamientos y otras urgencias en adultos e infantes. Menor variación se obtuvo en el primero y segundo, hecho que podemos atribuir, probablemente, a la sencillez de las preguntas y al mayor conocimiento previo de los asistentes. Esta información puede orientar futuras ediciones, ajustando estrategias y priorizando los talleres con mayor impacto educativo.

Por otro lado, en este estudio se analizaron diferencias entre dos Áreas de Salud de una misma provincia. En general, se observaron mayores conocimientos iniciales y asistencia en un Área, posiblemente, entre otros factores, a la captación más intensa, mayor número de hijos/as o mayor nivel educativo. Diversos estudios afirman que los conocimientos en salud se ven afectados por otros determinantes de la salud, como la geolocalización de la vivienda y el nivel socioeconómico18. Según varias fuentes19,20, existe una influencia positiva o negativa en conocimientos sanitarios y generales dependiendo de estos factores21. Se ha hecho una búsqueda de las dos zonas con el fin de analizar si existía una correlación entre tales conclusiones y los resultados de nuestro estudio. Todos estos factores descritos pueden tener efecto sumatorio en los conocimientos y asistencia de las familias. Aun así, vemos cómo en nuestro estudio esto no ha repercutido significativamente en los conocimientos previos y posteriores (con pequeñas diferencias, pero sin llegar a ser significativas entre las Áreas).

El estudio sugiere que la actividad atrae sobre todo a personas con mayor nivel educativo y formación sanitaria, lo que se refleja en la mayor asistencia en el Área Oeste (que tenía más formación previa en salud en un 5,24% respecto al área Este). Es posible que la difusión en RRSS y medios locales favorezca llegar a familias con mayor alfabetización digital, lo que condiciona un sesgo de selección hacia niveles educativos medios-altos. Por ello, planteamos realizar una captación activa de población de menor nivel socioeconómico y variante cultural. Actualmente, se ha hecho una adaptación del taller de alimentación en población de etnia gitana y de cuidados del bebé en población marroquí, con buena acogida y resultados subjetivos satisfactorios (no incluidos en el estudio, dado el pequeño tamaño muestral).

En cuanto a la satisfacción, ha sido muy positiva: 9 sobre 10. El que más interés ha despertado ha sido el de fiebre en infecciones respiratorias. Se refleja una clara unanimidad de respuestas positivas en satisfacción de este proyecto, muy semejantes a los resultados de satisfacción de otros estudios de promoción de la salud en Atención Primaria22-24.

Por último, hay que valorar que existen limitaciones en el proyecto; el corto período de evaluación tras la formación limita el estudio; sería útil complementarlo con una evaluación posterior.

Otro reto es que algunas familias se inscriben, pero no asisten por olvido, falta de tiempo, acceso, información en Internet o confianza en las consultas. Para adaptar todo lo posible el proyecto, enviamos recordatorios, ofrecimos horario de tarde y permitimos acudir con niños/as pequeños, y para familias marroquíes y gitanas se ofrecieron sesiones matutinas, adaptadas a su estilo de vida. Es preciso para futuros talleres realizar seguimiento del absentismo, escuchar los temas que desean tratar, animarlos a asistir y adaptarnos a sus necesidades. También valorar las sugerencias de algunas familias de combinar sesiones presenciales y online, con materiales digitales.

Desde el prisma de la preventiva, epidemiología y promoción de conceptos médico-sanitarios, este trabajo intenta reflejar la utilidad de la medicina activa, acercándose a la comunidad y respondiendo a necesidades sanitarias. Se ha demostrado una diferencia estadística de mejoría de las respuestas inmediatas, y los participantes agradecieron y expresaron, en formularios y presencialmente, haber aprendido y adquirido recursos sanitarios útiles para la crianza25. Esto respalda la importancia de promover la salud, especialmente en cuidados neonatales y pediátricos, y subraya la importancia de evaluar su impacto en hábitos de vida, enfermedades prevenibles y demanda asistencial mediante seguimiento del proyecto.

CONCLUSIONES

- Aunque la asistencia depende de varios factores, es necesario captar de manera más activa a las familias, especialmente las más vulnerables en determinantes sociales de la salud (DSS), para mejorar la participación y ofrecer una alfabetización en salud accesible.

- El taller que ha despertado más interés es el de primeros auxilios, seguido del de la fiebre e infecciones respiratorias.

- Este proyecto surge para responder a una necesidad en salud y ha evidenciado que los conocimientos previos han aumentado más del 16% tras los talleres.

- Los participantes valoraron positivamente la experiencia, señalando que les fue útil, aprendieron conceptos esenciales y adquirieron nuevas herramientas de crianza.

- Para poder comprobar los resultados en salud a largo plazo es preciso prolongar en el tiempo estas iniciativas y exportarlas a otras Áreas de Salud.

CONFLICTO DE INTERESES

Los autores declaran no presentar conflictos de intereses en relación con la preparación y publicación de este artículo.

RESPONSABILIDAD DE LOS AUTORES

Todos los autores han contribuido de forma equivalente en la elaboración del manuscrito publicado.

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Este proyecto es de carácter multidisciplinar, y no hubiera sido posible sin los equipos de Atención Primaria de Pediatría que integran el Área Este y Oeste de Valladolid. Agradecemos también a todo el equipo de enfermería pediátrica por su gran labor y cercanía.

Especialmente, agradecemos a los siguientes profesionales sanitarios: M.ª Cristina García de Ribera, Ana Fierro Urturi y M.ª Teresa Martínez Rivera como grupo motor y a Francisco Javier Ballesteros Gómez, M.ª del Pilar García Gutiérrez, Alejandra Romano Medina, Antonio Jesús Morales Moreno, Laura López Allue, M.ª José Martín Sierra, Pedro Prieto Zambrano, Ana Belén Camina Gutiérrez, Andrea Puebla Parral, Marta Santos Marinas, Susana Morillo Blanco, Rebeca Da Cuña Vicente, como colaboradores indispensables.

Por último, gracias también a las familias con interés de mejora de cuidados y salud de sus hijos/as.

ABREVIATURAS

AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria · APapCyL: Asociación de Pediatría de Atención Primaria de Castilla y León · CV: coeficiente de variabilidad · DE: desviación estándar · DSS: determinantes sociales de la salud · EIR: enfermero interno residente · EPS grupal: educación para la salud grupal · IC: intervalo de confianza · MIR: médico interno residente · OMS: Organización Mundial de la Salud · ProCC: procesos correctores comunitarios · RCP: reanimación cardiopulmonar · RN: recién nacido/a · RRSS: redes sociales · Sacyl: Sanidad de Castilla y León.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- World Health Organization. Educación para la salud: manual sobre educación sanitaria en atención primaria de salud. Ginebra: Organización Mundial de la Salud; 1989 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/38660

- Mosteiro Miguéns DG, Rodríguez Fernández A, Zapata Cachafeiro M, Vieito Pérez N, Represas Carrera FJ, Novío Mallón S. Community activities in primary care: a literature review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2024;15:21501319231223362. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231223362

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Determinantes sociales de la salud. Washington D.C.: OPS/OMS; 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://www.paho.org/es/temas/determinantes-sociales-salud

- Hernández-Díaz J, Paredes-Carbonell JJ, Marín Torrens R. Cómo diseñar talleres para promover la salud en grupos comunitarios. Aten Primaria. 2014;46(1):40–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2013.03.006

- Juvinyà-Canal D, Bertran-Noguer C, Suñer-Soler R. Alfabetización para la salud, más que información. Gac Sanit. 2018;32(1):8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.06.005

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Guía de acción comunitaria para ganar en salud. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad; 2021 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/entornosSaludables/local/estrategia/herramientas/docs/Guia_Accion_Comunitaria_Ganar_Salud.pdf

- Agencia Tributaria. Estadística de los declarantes del IRPF de los mayores municipios por código postal: 2022. Madrid: Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria; 2022 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/AEAT/Contenidos_Comunes/La_Agencia_Tributaria/Estadisticas/Publicaciones/sites/irpfCodPostal/2022/jrubik2ae7dc136b9bac0e57f31a18ba8184f49c36f6fb.html

- Agencia Tributaria. Estadística de los declarantes del IRPF de los mayores municipios por código postal: 2022. Madrid: Agencia Estatal de Administración Tributaria; 2022 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://sede.agenciatributaria.gob.es/AEAT/Contenidos_Comunes/La_Agencia_Tributaria/Estadisticas/Publicaciones/sites/irpfCodPostal/2022/jrubikf26c28cb47a6657073d8a750ca35a1a14e3f8f223.html

- Aguiló Pastrana E, Cucco M. Metodología de los procesos correctores comunitarios (metodología ProCC) [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://comunidad.semfyc.es/wp-content/uploads/Comunidad_MetodologiadelosProcesosCorrectoresComunitarios.pdf

- Cómo actuar con los niños ante una urgencia, virus respiratorios, obesidad infantil… En: El Norte de Castilla. 3 de febrero de 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en www.elnortedecastilla.es/valladolid/talleres-valladolid-ninos-urgencia-fiebre-virus-respiratorios-obesidad-20250203131147-nt.html

- Atención Primaria ofrece más talleres para padres sobre el cuidado de los hijos. En: El Día de Valladolid. 1 de febrero de 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en www.eldiadevalladolid.com/noticia/z8fb9789e-ae45-de53-07b33a9ff4ac9551/202502/atencion-primaria-ofrece-mas-talleres-de-pediatria-para-padres

- Ayuntamiento de Arroyo de la Encomienda. La Casa de Cultura acoge hoy el taller de educación para la salud «¿Es normal esto que le pasa a mi hijo?». X (antes Twitter). 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://x.com/AytoArroyo/status/1889580157226119550

- Salud comunitaria ASVAO. Instagram. 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en www.instagram.com/p/DG2mBrAsh-8/

- Ledesma I. Se reanudan los talleres del programa de educación para la salud de las áreas sanitarias de Valladolid. En: APapCyL. 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://apapcyl.es/se-reanudan-los-talleres-del-programa-de-educacion-para-la-salud-de-las-areas-sanitarias-de-valladolid/

- Pediatría de AP. Talleres: cuidando la salud de tu hijo. Portal Salud Junta Castilla y León. 2025 [en línea] [consultado el 24/09/2025]. Disponible en www.saludcastillayleon.es/HRHortega/en/actualidad/pediatria-ap-talleres-cuidando-salud-hijo

- Menor Rodríguez M, Aguilar Cordero M, Mur Villar N, Santana Mur C. Efectividad de las intervenciones educativas para la atención de la salud: revisión sistemática. MediSur. 2017 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1727-897X2017000100011

- Vázquez Fernández ME, Sanz Almazán M, García Sanz S, Berciano Villalibre C, Alfaro González M, del Río López A. Intervención educativa en atención primaria para reducir y mejorar la adecuación de las consultas pediátricas. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2020;93:e201901003.

- Nieuwenhuis J, Kleinepier T, van Ham M. The role of exposure to neighborhood and school poverty in understanding educational attainment. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(5):872-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01394-2

- Corella Piquer D, Ordovás Muñoz JM. Relación entre el estado socioeconómico, la educación y la alimentación saludable. Mediterráneo Económico. 2015;(27):283-306 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5207080

- Chaudry A, Wimer C. Poverty is not just an indicator: the relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):S23-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.010

- Martens PJ, Chateau DG, Burland EMJ, Finlayson GS, Smith MJ, Taylor CR, et al. The effect of neighborhood socioeconomic status on education and health outcomes for children living in social housing. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2103-13. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302133

- Díaz Sánchez MC. Valoración de la satisfacción de pacientes que acuden a talleres de educación para la salud en la unidad de hospitalización breve. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 2017 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/687171

- Vaquero Barba A, Garai Ibáñez de Elejalde B, Ruiz de Arcaute Graciano J. La importancia de las experiencias positivas y placenteras en la promoción de la actividad física orientada hacia la salud. Ágora Para Educ Física Deporte [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/23792

- Herranz BJ, Pastor VML, Garzarán AP. Satisfacción de los diferentes agentes que participan en el desarrollo de un programa municipal de deporte escolar. Alto Rendimiento. 2013;146-50 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://portaldelaciencia.uva.es/documentos/61b994d88bc05f42e937cd9e

- Cofiño Fernández R, Álvarez Muñoz B, Fernández Rodríguez S, Hernández Alba R. Promoción de la salud basada en la evidencia: ¿realmente funcionan los programas de salud comunitarios? Aten Primaria. 2005;35(9):478-83. https://doi.org/10.1157/13075472

- Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Decálogo de la fiebre. En: Familia y Salud. 2014 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en www.familiaysalud.es/recursos/decalogos-aepap/decalogo-de-la-fiebre

- Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús. Guía práctica de primeros auxilios para padres. Madrid: Hospital Niño Jesús; 2017 [en línea] [consultado el 02/09/2025]. Disponible en https://somprematurs.cat/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Guia-Primeros-auxiliosHospital-Nino-Jesus-1.pdf