Vol. 17 - Num. 68

Originales

Alivio del dolor y el estrés al vacunar. Síntesis de la evidencia. Recomendaciones del Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la AEP

Nuria García Sáncheza, Manuel Merino Moínab, César García Verac, I Lacarta Garcíad, L Carbonell Muñoze, Beatriz Pina Marquésf, FJ Álvarez Garcíag, J Arístegui Fernándezh, en nombre del Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (CAV-AEP)

aPediatra. CS Delicias Sur. Zaragoza. España.

bPediatra. CS El Greco. Getafe. Madrid. España.

cPediatra. CS José Ramon Muñoz Fernández. Zaragoza. España.

dMIR-Anestesiología, Reanimación y Terapia del dolor. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Zaragoza. España.

eEnfermera de Pediatría. CS Parque Coimbra. Móstoles. Madrid. España.

fMatrona. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Zaragoza. España.

gPediatra. CS de Llanera. Departamento de Medicina. Universidad de Oviedo. Asturias. España.

hUnidad de Infectología Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario de Basurto. Departamento de Pediatría. Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU). Bilbao. España.

Correspondencia: N García. Correo electrónico: nuriagarciasanchez4@gmail.com

Cómo citar este artículo: García Sánchez N, Merino Moína M, García Vera C, Lacarta García I, Carbonell Muñoz L, Pina Marqués B, et al. Alivio del dolor y el estrés al vacunar. Síntesis de la evidencia. Recomendaciones del Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la AEP. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015;17:317-27.

Publicado en Internet: 19-11-2015 - Número de visitas: 91018

Resumen

Introducción: en niños y adolescentes sanos, las vacunaciones son con frecuencia fuente de dolor y sufrimiento. Padres, niños, adolescentes y profesionales sanitarios muestran preocupación sobre ello. El Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (CAV-AEP) cree que abordar el dolor y el sufrimiento al vacunar es necesario, siguiendo la metodología de la medicina basada en la evidencia. El objetivo del presente trabajo es elaborar recomendaciones basadas en el conocimiento científico.

Material y métodos: se dividió la materia de estudio en cuatro áreas: amamantamiento y soluciones azucaradas, anestésicos tópicos, métodos para la administración de vacunas y otras intervenciones (distracción). Se realizó una síntesis de la evidencia, asumiendo las recomendaciones de la Guía de práctica clínica de Anna Taddio (2010) e incorporando la evidencia de revisiones sistemáticas y ensayos clínicos posteriores a los incorporados en dicha guía.

Resultados: las medidas que se han mostrado efectivas en la disminución del dolor han sido las siguientes: en lactantes, amamantar antes, durante y después de la inyección; las soluciones azucaradas son una alternativa si la lactancia materna no fuera posible; los anestésicos tópicos son eficaces para todas las edades, pero requieren un tiempo para mostrar su efecto y tienen un coste; no aspirar en la inyección intramuscular y hacerlo lo más rápido posible; administrar las vacunas de forma que la más dolorosa sea la última; cuando sea posible, es preferible inyectar simultáneamente más de una vacuna que hacerlo de forma secuencial; sostener al niño en brazos; y utilizar maniobras de distracción para niños de 2-14 años.

Conclusiones: realizada una exhaustiva revisión del tema, hay pruebas suficientes para afirmar que los profesionales que administran vacunas infantiles deberían poner en práctica medidas para atenuar el dolor que indudablemente acompaña al procedimiento de la vacunación. Se trata además, en general, de medidas técnicamente sencillas y fáciles de incorporar a la práctica.

Palabras clave

● Anestesia y analgesia ● Control del dolor ● Dolor ● Inmunización ● VacunaciónNota:

iMiembros del CAV-AEP: D. Moreno Pérez, F. J. Álvarez García, J. Arístegui Fernández, M. J. Cilleruelo Ortega, J. M. Corretger Rauet, N. García Sánchez, A. Hernández Merino, M. T. Hernández-Sampelayo Matos, M. Merino Moína, L. Ortigosa del Castillo, J. Ruiz Contreras

INTRODUCCIÓN

Los temas relacionados con el dolor en niños pequeños han sido objeto de poca atención en décadas previas, posiblemente concepciones erróneas respecto a la percepción del dolor y el desconocimiento de las técnicas analgésicas y anestésicas nos han llevado a la rutina de desatender el dolor durante la vacunación infantil1. Investigaciones bien fundadas sustentan que en los lactantes existe capacidad anatómica y funcional para percibir el dolor2, y se han observado respuestas tisulares ante una agresión que pueden interpretarse como respuesta al dolor3,4.

La administración de vacunas es el procedimiento doloroso que se realiza con más frecuencia en la infancia a niños sanos. La falta de un manejo adecuado del dolor durante el acto de la vacunación expone a los niños a un sufrimiento innecesario y puede ser el origen de consecuencias a largo plazo como el temor a las agujas y a la atención sanitaria5. Los niños entre 4 y 14 años expresan sus deseos de ser preparados con antelación a la vacunación y solicitan técnicas para disminuir el dolor durante el procedimiento6.

Muchas publicaciones abordan esta materia, pero pocos profesionales han integrado estas recomendaciones en su práctica habitual, por desconocimiento o creencias erróneas. La difusión de estas técnicas y la enseñanza a los clínicos ha conducido a un mayor uso de las mismas, un incremento en la satisfacción de profesionales, familias y pacientes y un mejor cumplimiento del calendario vacunal infantil7-9.

El Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la Asociación Española de Pediatría (CAV-AEP) ha visto la necesidad de que un equipo multidisciplinar elabore una guía o conjunto de recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia para el control del dolor durante el acto de la vacunación infantil. Los objetivos que se pretenden son: hacer del acto de la vacunación un momento menos estresante, humanizar el acto de la vacunación, conseguir una mayor adherencia a los calendarios vacunales infantiles y disminuir las secuelas psicológicas a largo plazo por las experiencias negativas con el dolor.

MATERIAL Y MÉTODOS

Metodología para la revisión y síntesis de la evidencia

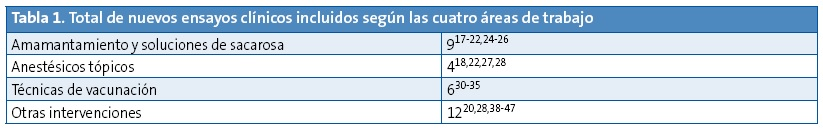

Para realizar este documento, el equipo elaborador dividió en cuatro bloques los aspectos a estudiar en relación al dolor provocado por la técnica vacunal (amamantamiento o ingesta de soluciones de sacarosa, anestésicos tópicos, otros métodos físicos incluyendo maniobras de distracción, y técnicas de inyección). El equipo decidió asumir, por su calidad, las recomendaciones de la guía de práctica clínica basada en la evidencia de Anna Taddio5 y de las revisiones sistemáticas Cochrane sobre estos temas10-15. A partir de las fechas en que finalizaron las búsquedas de esta guía o las correspondientes revisiones sistemáticas mencionadas, se realizó la del equipo en las siguientes bases de datos electrónicas: TripDatabase, Cochrane, Epistemonikos, Cinhal, Centre for Review Dissemination, PubMed, Embase, Biblioteca Virtual en Salud y Sumarios IME y CUIDEN (hasta febrero de 2015). No se aplicó restricción de lenguaje, pero solamente se valoraron ensayos clínicos controlados o no controlados. Se revisó también la bibliografía de estos artículos. Se recuperaron finalmente 27 publicaciones (Tabla 1): nueve sobre amamantamiento y soluciones de sacarosa, cuatro sobre anestésicos tópicos, 12 sobre otros métodos y seis sobre la técnica de vacunación. Los artículos fueron evaluados según la herramienta de la Colaboración Cochrane de riesgo de sesgos16.

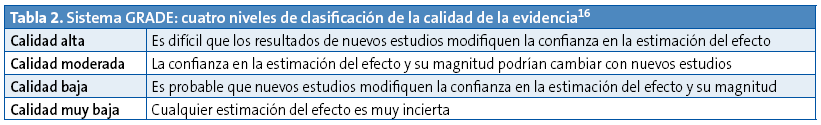

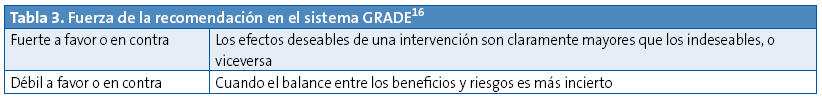

Para clasificar la evidencia y graduar la fuerza de la recomendación se decidió utilizar la clasificación GRADE (Tablas 2 y 3)17. El sistema GRADE solo tiene dos categorías para designar la fuerza de las recomendaciones:

- Fuerte: existe un alto grado de confianza en que los efectos deseables de la intervención superan a los no deseables (recomendación fuerte a favor) o viceversa (recomendación fuerte en contra).

- Débil: probablemente los efectos deseables de la intervención superan a los no deseables (recomendación débil a favor), o viceversa (recomendación débil en contra), pero existe menor grado de certeza.

Las recomendaciones que no resulten claras tras seguir este proceso, pero que cuentan con el consenso del equipo revisor, se señalarán como tales (recomendación de los autores).

RESULTADOS

Amamantamiento e ingesta de soluciones azucaradas

Amamantamiento

La lactancia al pecho es la manera natural y mejor de alimentar a niños pequeños. Las mujeres que amamantan, intuitivamente, ofrecen a sus hijos el pecho para proporcionarles no solo alimento, sino también alivio en momentos de dolor o enfermedad; asimismo, el lactante busca el seno materno cuando necesita consuelo.

Disponemos de pruebas científicas claras y robustas de que el amamantamiento, en comparación con el placebo o la no intervención, reduce los signos de dolor derivado de procedimientos dolorosos simples (venopunción, inyección intramuscular, punción del talón, etc.) realizados en lactantes pequeños. Dar de mamar, como método analgésico, es superior a la administración directa de leche humana o de soluciones dulces, al uso del chupete estando el niño en brazos u otros métodos de analgesia no farmacológica5-10,17-21. También se ha observado su acción sinérgica con la analgesia farmacológica tópica22.

Amamantar se considera como una técnica analgésica combinada, pues reúne distracción por la succión, liberación de opioides endógenos debido al sabor dulce, contacto piel con la piel y efecto antiestrés por la liberación de oxitocina y, posiblemente, de melatonina.

Por otro lado, y respecto a la recepción en el mismo acto de vacunas vivas orales, estudios recientes no han encontrado asociación entre el amamantamiento alrededor de la administración de la vacuna frente al rotavirus y la inmunogenicidad resultante23.

En cuanto a la técnica idónea, es importante dar tiempo a que el agarre al pecho sea efectivo antes de llevar a cabo el procedimiento doloroso. El amamantamiento debe mantenerse durante todo el tiempo que dure la administración de las vacunas inyectables e idealmente mantenerse, también, después.

No se han notificado efectos adversos, del tipo de atragantamiento y similares, como consecuencia de esta práctica. Los inconvenientes ergonómicos que puede suponer la vacunación mientras el niño es amamantado son menores y están altamente compensados por los beneficios de esta práctica.

Recomendación 1: se recomienda amamantar a los lactantes durante las vacunaciones como mejor método analgésico y de consuelo (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Soluciones dulces

La administración oral de glucosa o sacarosa es una técnica analgésica útil y segura, de uso habitual ante la realización de procedimientos dolorosos en neonatos11. Hay actualmente más de 100 ensayos clínicos que comparan la administración de sustancias dulces frente a otras intervenciones y placebo en diferentes edades pediátricas.

Junto con la distracción, el efecto analgésico de la administración de sacarosa parece mediado por receptores gustativos orales y se considera que es debido a la liberación de opioides endógenos mesencefálicos.

El poder analgésico de esta intervención previa a estímulos dolorosos, como la inyección de vacunas, está relacionado con la edad, siendo más marcado en neonatos, apreciable por debajo de 12 meses y menos evidente por encima del año de edad5,11-13,24,25. Sin embargo, un estudio reciente encuentra significación estadística en favor de su uso en niños de 16-18 meses, especialmente con concentraciones elevadas de sacarosa (75%)26.

Este método puede combinarse con la succión del chupete, pero no se recomienda como tratamiento del dolor en otras circunstancias.

No está establecida la pauta más adecuada ni la concentración y volumen idóneos a administrar, pero se recomienda aplicarlo 1-2 minutos antes de la punción. Las pautas más habituales son la administración única de 12-25 g de sacarosa en 10 ml de agua, en función de la edad5,17.

Recomendación 2: si no es posible el amamantamiento, en niños de hasta 18 meses de edad se recomienda la administración oral de una solución dulce de agua con sacarosa, previa a la inyección de vacunas (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Anestésicos tópicos

El control del dolor durante la vacunación infantil requiere la combinación de diversas técnicas por su efecto sinérgico. La utilización de un anestésico tópico solo o combinado es muy eficaz. Entre los fármacos utilizados destacan la crema EMLA®, mezcla de los anestésicos tópicos lidocaína-prilocaína (2,5%), lidocaína crema (Lambdalina®) y el espray frío de cloruro de etilo (Cloretilo Chemirosa®). EMLA® es el más utilizado, pues puede usarse desde el periodo neonatal, mientras que Lambadalina® requiere una edad de seis años y hay menos experiencia con el cloruro de etilo (solo un artículo y fue menos eficaz que la lactancia materna en niños menores de seis meses)18.

Diversos trabajos han demostrado un beneficio claro en la aplicación de estos fármacos para minimizar el dolor durante la vacunación18,22. Algunas sociedades científicas incluyen, en sus guías de vacunación, el uso de anestésicos tópicos, fundamentalmente la crema EMLA®5,14. Se ha demostrado una disminución estadísticamente significativa de diversas escalas de dolor validadas internacionalmente, como la Escala Visual Analógica (EVA)27 y otras como afectación del comportamiento, tiempo de duración del llanto o puntuaciones sobre expresiones faciales28.

Respecto a la crema EMLA®, hay que destacar su elevado nivel de seguridad y que para conseguir el efecto anestésico deseado requiere su aplicación una hora antes de la inyección. La eficacia del producto radica en su buena penetración, hasta 5 mm, produciendo anestesia superficial eficaz como para realizar incluso pequeñas intervenciones. Así como otras técnicas ofrecen peores resultados en niños mayores (lactancia materna, soluciones de sacarosa), los anestésicos tópicos mantienen su eficacia en cualquier edad. La cantidad requerida, del tamaño de una moneda, cubierto por un apósito, no se asocia a metahemoglobinemia.

Recomendación 3: el uso de anestésicos tópicos, como cremas tipo EMLA®, con la antelación suficiente, se recomienda a cualquier edad pediátrica para la prevención del dolor asociado a la vacunación (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Técnicas de administración de las vacunas

Este apartado hace referencia a todas las técnicas relacionadas con la punción para la aplicación del preparado vacunal.

Marca de la vacuna

En algunos casos, existen diferentes formulaciones para la misma vacuna. Determinados preparados producen más dolor que otros frente a idénticos antígenos5,29.

Recomendación 4: elegir la marca de vacuna menos dolorosa, cuando sea posible (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Posición

La posición supina resulta más dolorosa que cuando el niño es sostenido por sus padres5 o mediante el contacto piel con piel en el periodo neonatal30. La sujeción no debe ser demasiado firme para evitar aumentar el temor del niño.

Recomendación 5: evitar la posición supina (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Técnica de inyección

La administración lenta de las vacunas, junto a la aspiración, ha resultado ser más dolorosa5,31.

Recomendación 6: aplicar las vacunas intramusculares utilizando una técnica de administración rápida y sin aspiración (recomendación fuerte a favor).

Orden de administración de las vacunas

En ocasiones, es necesario administrar dos o más vacunas en una misma visita. Debido a que algunas vacunas duelen más que otras y el dolor puede aumentar con cada inyección, el orden con el que las administramos puede influir en la respuesta de dolor5,32,33.

Recomendación 7: cuando se administran varias vacunas secuencialmente, aplicar la más dolorosa en último lugar (recomendación débil a favor).

Vías de administración

Algunas vacunas pueden ser administradas por vía intramuscular o por vía subcutánea. Actualmente no existe evidencia de que una u otra vía resulte menos dolorosa, no obstante, se estima que la vía subcutánea tiene mayor potencial de reactogenicidad local posterior.

Recomendación 8: asegurar que la inyección intramuscular se pone en el plano adecuado. Esto no supone más o menos dolor en el momento de la inyección, pero sí puede mejorar la experiencia sensorial posterior (recomendación por consenso de los autores).

Inyección múltiple

La administración de vacunas por dos personas al mismo tiempo se postula como un método eficaz en la reducción del dolor en lactantes34,35.

Recomendación 9: administrar las vacunas a lactantes de forma simultánea y no secuencial, si hay disponibilidad de profesionales (recomendación débil a favor).

Temperatura

La evidencia disponible no avala el calentamiento de la vacuna como medida para disminuir el dolor durante la administración7,36, aunque frotar la vacuna entre las manos garantiza una mezcla más homogénea de los componentes de la vacuna.

Recomendación 10: frotar la vacuna entre las manos antes de la administración (recomendación por consenso de los autores).

Lugar de inyección

Elegir la zona adecuada para la administración de las vacunas (antes de la deambulación, el tercio medio del vasto externo, y posteriormente el deltoides) garantiza la inmunogenicidad y reduce el número de reacciones adversas37.

Recomendación 11: elegir la zona de punción que garantice la administración por la vía indicada, según la edad y características del niño (recomendación débil a favor).

Tamaño de las agujas

La elección de una aguja corta hace que el contenido de la vacuna se quede en el tejido subcutáneo, provocando más efectos adversos, tales como reactogenicidad local y dolor, en aquellas vacunas que precisan de una administración intramuscular36,37.

Recomendación 12: elegir una aguja suficientemente larga que permita llegar al músculo, dependiendo de zona de administración, edad y características del niño (recomendación débil a favor).

Otras intervenciones

En este apartado se incluyen todas las técnicas distintas a las explicadas anteriormente, y que algunos autores denominanintervenciones psicológicas, intervenciones no farmacológicas, etc.

Maniobras de distracción

Algunos autores describen estas maniobras como una de las intervenciones clave para el control del dolor en la vacunación36. Se ha teorizado que centrar la atención hacia estímulos distintos a la vacunación puede afectar el procesamiento y percepción del dolor, pero además, estudios neurofisiológicos ponen de manifiesto que las áreas del cerebro relacionadas con el procesamiento del estímulo doloroso se muestran menos activas durante la realización de tareas de distracción.

Las intervenciones psicológicas aplicadas a procedimientos dolorosos y estresantes relacionados con uso de agujas, han sido ampliamente estudiadas, siendo objeto de una extensa revisión de la Cochrane14 y de otra revisión sistemática previa38. Los trabajos se han centrado en niños de 2 a 19 años que han requerido punciones, entre ellas inmunizaciones. Como resumen, destacar que la revisión de Uman y los ensayos incluidos posteriormente ofrecen suficiente evidencia de que intervenciones psicológicas, como las maniobras de distracción, en especial en niños de edad inferior a 12 años, son técnicas efectivas en el control del dolor y malestar generado por el procedimiento14,28,39-43. No se han encontrado pruebas para otras técnicas disuasorias14.

La revisión sistemática posterior de Chambers38 confirma la eficacia de intervenciones sencillas, como ejercicios de respiración amplios y lentos, maniobras de distracción dirigidas por el niño o el profesional de enfermería, usando dispositivos y métodos apropiados para la edad, así como intervenciones cognitivo-conductuales en la reducción del dolor y el sufrimiento durante la vacunación. Las técnicas de distracción que se proponen son sencillas: leer un cuento o historia, oír música, mirar una pantalla y, en general, concentrarse en cualquier otra cosa que no sea la inyección. Se ha descrito el uso de dispositivos electrónicos como tabletas, videojuegos, aparatos para oír música, estos especialmente indicados en adolescentes. En el grupo de 14 años o más hay pocos estudios, pero un ensayo clínico aleatorizado encuentra evidencia de disminución del dolor al ser vacunados utilizando música, incluso sin necesidad de cascos44. Hay que destacar que todas estas intervenciones son sencillas, no requieren un presupuesto significativo y aportan gran beneficio. En caso de utilizar juguetes, deberán ser limpiados adecuadamente entre un usuario y el siguiente, para evitar que se comporten como fómites.

Recomendación 13: en niños de 2 a 19 años utilizar técnicas de distracción, como leer una historia u oír música (recomendación fuerte a favor). En adolescentes de 14 años, utilizar música sin auriculares (recomendación débil a favor).

Estimulación táctil

Acariciar, frotar o presionar la piel próxima al lugar de inyección es una intervención sin coste que puede reducir el dolor de la vacuna. Debe hacerse antes y durante la inyección, pero no después, porque se podría incrementar la reactogenicidad. Esta técnica se basa en la hipótesis de que la sensación táctil compite con la sensación de la punción y así esta resulta menos dolorosa. Dado que existen pocos estudios en niños pequeños, en los que, además, el procedimiento puede suponer una sensación negativa, estas técnicas se recomiendan para mayores de cuatro años, en los que hay estudios cuasiexperimentales5. Para lactantes y recién nacidos, el estímulo táctil debería ser muy cuidadoso y acompañado por otras técnicas, denominadas “saturación sensorial”, que consisten en proporcionar estímulos multisensoriales basados en los sentidos del tacto, gusto, audición y visión; por ejemplo, hablar, acariciar la cara y proporcionar soluciones azucaradas20,42,45-47.

Recomendación 14: en niños de cuatro años o mayores, frotar o acariciar la piel cerca del lugar de inyección, con intensidad moderada, antes y durante la administración (recomendación débil a favor).

DISCUSIÓN

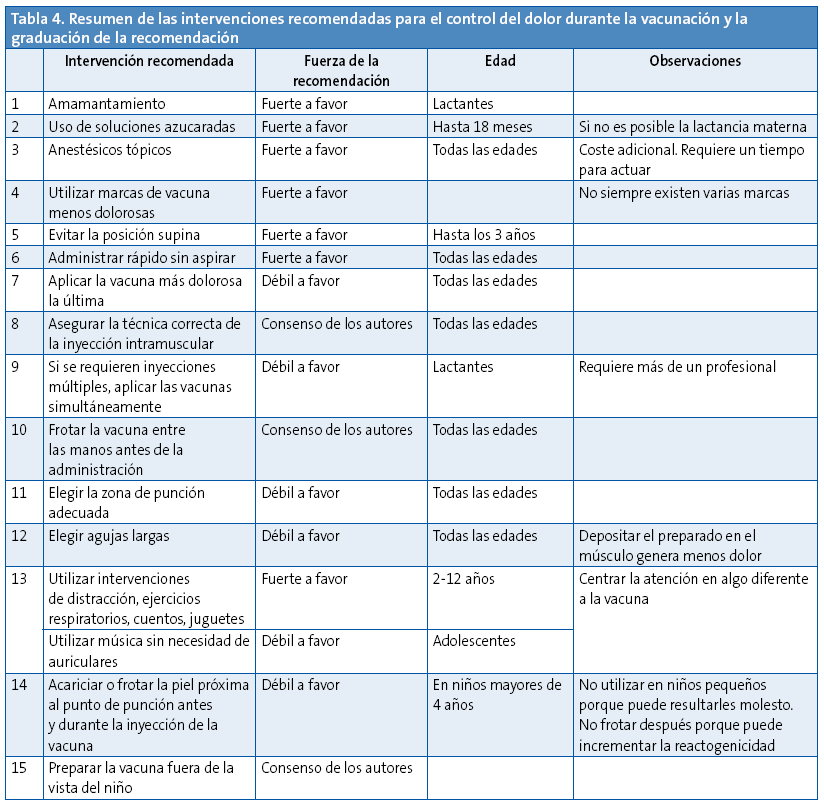

Como conclusión, podemos decir que, a la luz de la evidencia disponible, se deben utilizar todas aquellas técnicas que se han mostrado efectivas en el control del dolor y sufrimiento durante el acto de la vacunación (Tabla 4). No se justifica desatender este aspecto por la efectividad que estos procedimientos han mostrado.

La complejidad de los calendarios vacunales se va incrementando conforme se dispone de nuevas vacunas, seguras y eficaces. A pesar de existir muchas publicaciones sobre técnicas que pueden facilitar el control del dolor, no es frecuente en nuestro medio encontrar profesionales que tengan estos procedimientos integrados en su práctica habitual. Con este trabajo se pretende aportar una síntesis de la evidencia disponible para conocer qué técnicas tienen un sustento científico suficiente como para ser recomendadas. En el listado de recomendaciones solo hemos añadido aquellas basadas en ensayos clínicos posteriores a la guía de práctica clínica de Taddio5 y las revisiones sistemáticas Cochrane9-14 sobre estos temas, cuyas conclusiones fueron asumidas inicialmente por los autores.

Existen procedimientos considerados como de buena práctica clínica y que de hecho aconsejamos, pero por no existir trabajos con evidencia que los sustenten figuran como consenso de los autores, como por ejemplo atemperar la vacuna frotándola entre las manos, o bien que el sanitario haga la preparación de la vacuna en un lugar fuera de la vista del niño que va a recibirla (recomendación 15) y asegurar que la inyección intramuscular se pone en el plano adecuado.

Una vez concluido el periodo de búsqueda bibliográfica y realización de este trabajo de síntesis de la evidencia, comprobamos con satisfacción como la propia Organización Mundial de la Salud recomendó que, en todo lugar que se administren vacunas, se incluyan técnicas para mitigar el dolor48. Recientemente A. Taddio ha publicado una nueva guía de práctica clínica49 que actualiza los conocimientos de la anterior y extiende las recomendaciones a toda la etapa vital, pues incluye a los adultos. Al igual que nosotros, A. Taddio y su equipo utilizan el sistema GRADE para establecer las recomendaciones. Nos sentimos satisfechos de que con nuestra revisión hayamos llegado, de forma paralela en el tiempo y sin conocer sus investigaciones, a resultados muy similares. Únicamente pequeñas diferencias podrían detectarse, por ejemplo, la aplicación de la vacuna más dolorosa la última nosotros lo indicamos como recomendación débil a favor, mientras que Taddio la considera fuerte a favor. La utilización de intervenciones de distracción es considerada por Taddio como débil a favor y por nosotros fuerte a favor. Asimismo, ellos añaden como recomendaciones fuertes a favor la formación de profesionales, padres y niños mayores de tres años respecto al control del dolor durante la vacunación. En el apartado de soluciones azucaradas proponen como alternativa el uso de la vacuna oral de rotavirus en los niños en que esté programada su administración50.

Este trabajo no finaliza con la elaboración del presente escrito. Deberíamos ser capaces de transmitir a los pediatras y a los profesionales de enfermería que administrar vacunas controlando (mitigando) el dolor y el estrés es una práctica clínica de excelencia. No requiere nada más que un adiestramiento sencillo, que se obtiene con la lectura de estas recomendaciones, en general no supone coste añadido, ni para su aplicación se requiere de tiempo adicional. Además, los profesionales que las aplican manifiestan habitualmente mayor satisfacción y su aplicación puede favorecer un mejor cumplimiento del calendario vacunal.

CONFLICTO DE INTERESES

Los autores declaran no presentar conflictos de intereses en relación con la preparación y publicación de este artículo.

ABREVIATURAS: CAV-AEP: Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la Asociación Española de Pediatría.

AGRADECIMIENTOS

A Ángel Hernández Merino, por sus aportaciones en la fase de redacción del texto. Al CAV-AEP, por el apoyo determinante al proyecto en su conjunto.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

- Taddio A, Chambers C, Halperin S, Ipp M, Lockett D, Rieder MJ, et al. Inadequate pain management during childhood immunization: the nerve of it. Clin Ther. 2009;31:S152-67.

- Fitzgerald M. The development of nociceptive circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:507-20.

- Slater R, Cornelissen L, Fabrizi L, Patten D, Yoxen J, Worley A. Oral sucrose as an analgesic drug for procedural pain in newborn infants: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1225-32.

- Grunau R, Craig KD. Pain expression in neonates: facial action and cry. Pain. 1987;28:395-410.

- Taddio A, Appleton M, Bortolussi R, Chambers C, Dubey V, Halperin S, et al. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (summary). CMAJ. 2010;182:e843-e55.

- Taddio A, Ilersich AF, Llersich AN, Wells J. From the mouth of babes: getting vaccinated doesn’t have to hurt. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2014;25:196-200.

- Schechter NL, Bernstein BA, Zempsky WT, Bright NS, Willard AK. Educational outreach to reduce immunization pain in office settings. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1514-21.

- Chan S, Pielak K, McIntyre C, Deeter B, Taddio A. Implementation of a new clinical practice guideline regarding pain management during childhood vaccine injections. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18:367-72.

- Pillai Riddell RR, Racine NM, Turcotte K, Uman LS, Horton RE, Din Osmun L, et al. Non-pharmacological management of infant and young child procedural pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD006275.

- Shah PS, Herbozo C, Aliwalas LL, Shah VS. Breastfeeding or breast milk for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004950.

- Stevens B, Yamada J, Lee GY, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD001069.

- Kassab M, Foster JP, Foureur M, Fowler C. Sweet-tasting solutions for needle-related procedural pain in infants one month to one year of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD008411.

- Harrison D, Yamada J, Adams-Webber T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Stevens B. Sweet tasting solutions for reduction of needle-related procedural pain in children aged one to 16 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:CD008408.

- Uman LS, Birnie KA, Noel M, Parker JA, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, et al. Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD005179.

- Higgins JPT, Green S (eds.). Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, versión 5.1.0. En: Cochrane Iberoamérica [en línea] [actualizado en marzo de 2011, consultado el 19/11/2015]. Disponible en http://es.cochrane.org/sites/es.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Manual_Cochrane_510_reduit.pdf

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924-6.

- McNair C, Campbell Yeo M, Johnston C, Taddio A. Nonpharmacological management of pain during common needle puncture procedures in infants: current research evidence and practical considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40:493-508.

- Boroumandfar K, Khodaei F, Abdeyazdan Z, Maroufi M. Comparison of vaccination-related pain in infants who receive vapocoolant spray and breastfeeding during injection. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:33-7.

- Modarres M, Jazayeri A, Rahnama P, Montazeri A. Breastfeeding and pain relief in full-term neonates during immunization injections: a clinical randomized trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:22.

- Esfahani MS, Sheykhi S, Abdeyazdan Z, Jodakee M, Boroumandfar K. A comparative study on vaccination pain in the methods of massage therapy and mothers' breast feeding during injection of infants referring to Navabsafavi Health Care Center in Isfahan. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:494-8.

- Iqbal A, Malik R, Siddique M, Yaqub M, IqbalT, Farrukh H, et al. Breast feeding of pain relief during Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccination in term neonates. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2014;8:403-6.

- Gupta NK, Upadhyay A, Agarwal A, Goswami G, Kumar J, Sreenivas V. Randomized controlled trial of topical EMLA and breastfeeding for reducing pain during wDPT vaccination. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1527-33.

- Rongsen-Chandola T, Strand TA, Goyal N, Flem E, Rathore SS, Arya A, et al. Effect of withholding breastfeeding on the immune response to a live oral rotavirus vaccine in North Indian infants. Vaccine. 2014;32:A134-9.

- Curry DM, Brown C, Wrona S. Effectiveness of oral sucrose for pain management in infants during immunizations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2012;13:139-49.

- Goswami G, Upadhyay A, Gupta NK, Chaudhry R, Chawla D, Sreenivas V. Comparison of analgesic effect of direct breastfeeding, oral 25% dextrose solution and placebo during 1st DPT vaccination in healthy term infants: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:649-53.

- Yilmaz G, Caylan N, Oguz M, Karacan CD. Oral sucrose administration to reducepain response during immunization in 16-19-month infants: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1527-32.

- Abuelkheir M, Alsourani D, Al-Eyadhy A, Temsah MH, Meo SA, Alzamil F. EMLA© cream: a pain-relieving strategy for childhood vaccination. J Int Med Res. 2014;42:329-36.

- Boivin JM, Poupon-Lemarquis L, Iraqi W, Fay R, Schmitt C, Rossignol P. A multifactorial strategy of pain management is associated with less pain in scheduled vaccination of children. A study realized by family practitioners in 239 children aged 4-12 years old. Fam Pract. 2008;25:423-9.

- Knutsson N, Jansson UB, Alm B. Immediate injection pain in infants aged 18 months during vaccination against measles, mumps and rubella with either Priorix or MMR-II. Vaccine. 2006;24:5800-5.

- Kostandy R, Anderson GC, Good M. Skin-to-skin contact diminishes pain from hepatitis B vaccine injection in healthy full-term neonates. Neonatal Netw. 2013;32:274-80.

- Girish GN, Ravi MD. Vaccination related pain: comparison of two injection techniques. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:1327-31.

- Sánchez-Molero Martín MP, del Cerro Gutiérrez AM, Galán Delgado H, Muñoz Camargo JC. Respuesta al dolor de lactantes, según el orden de administración de las vacunas. Rev Enferm. 2014;37:50-7.

- Ipp M, Parkin PC, Lear N, Goldbach M, Taddio A. Order of vaccine injection and infant pain response. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:469-72.

- McGowan A, Cottrell S, Roberts R, Lankshear A. Minimising pain response during routine infant immunization. Community Pract. 2013;86:24-8.

- Hanson D, Hall W, Mills LL, Au S, Bhagat R, Hernandez M, et al. Comparison of distress and pain in infants randomized to groups receiving standard versus multiple immunizations. Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33:289-96.

- Schechter N, Zempsky W, Cohen L, McGrath PJ, McMurtry CM, Bright NS. Pain reduction during pediatric immunizations: evidence-based review and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1184-98.

- Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la AEP. Manual de vacunas en línea de la AEP: El acto de la vacunación; antes, durante y después. En: CAV-AEP [actualizado en noviembre de 2014, consultado el 19/11/2015]. Disponible en http://vacunasaep.org/printpdf/documentos/manual/cap-5

- Chambers CT, Taddio A, Uman LS, McMurtry CM, HELPinKIDS Team. Psychological interventions for reducing pain and distress during routine childhood immunizations: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2009;31:S77-103.

- Harrington JW, Logan S, Harwell C, Gardner J, Swingle J, McGuire E, et al. Effective analgesia using physical interventions for infant immunizations. Pediatrics. 2012;129:815-22.

- Beran TN, Ramirez-Serrano A, Vanderkooi OG, Kuhn S. Reducing children's pain and distress towards flu vaccinations: a novel and effective application of humanoid robotics. Vaccine. 2013;31:2772-7.

- Shahid R, Benedict C, Mishra S, Mulye M, Guo R. Using iPads for distraction to reduce pain during immunizations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:145-8.

- Gray L, Garza E, Zageris D, Heilman KJ, Porges SW. Sucrose and warmth for analgesia in healthy newborns: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e607-14.

- Hillgrove-Stuart J, Pillai Riddell R, Horton R, Greenberg S. Toy-mediated distraction: clarifying the role of agent of distraction and preneedle distress in toddlers. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:197-202.

- Kristjánsdóttir O, Kristjánsdóttir G. Randomized clinical trial of musical distraction with and without headphones for adolescents' immunization pain. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:19-26.

- Taddio A, Ho T, Vyas C, Thivakaran S, Jamal A, Ilersich AF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of clinician-led tactile stimulation to reduce pain during vaccination in infants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53:639-44.

- Hogan ME, Probst J, Wong K, Riddell RP, Katz J, Taddio A. A randomized-controlled trial of parent-led tactile stimulation to reduce pain during infant immunization injections. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:259-65.

- Nakashima Y, Harada M, Okayama M, Kajii E. Analgesia for pain during subcutaneous injection: effectiveness of manual pressure application before injection. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:817-20.

- Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization, April 2015: conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2015;90:261-78.

- Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, Riddell RP, Chambers CT, Noel M, et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2015;187:975-82.

- Taddio A, Flanders D, Weinberg E, Lamba S, Vyas C, Ilersich AF, et al. A randomized trial of rotavirus vaccine versus sucrose solution for vaccine injection pain. Vaccine. 2015;33:2939-43.