Vol. 27 - Num. 107

Original Papers

Analysis of referrals for phimosis to specialist care: What happens next?

Sara Fuentes Carreteroa, Carme Grande Moreillob, Alicia Arranz Martíc, Paula Salcedo Arroyod, Elena Robert Gilc, M.ª Esperanza Martín Castilloc, Nerea Vicente Sáncheze

aServicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario MútuaTerrasa. Terrasa. Barcelona. España.

bServicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa. Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedès i Garraf. Sant Pere de Ribes. Barcelona. España.

cServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario MútuaTerrasa. Terrasa. Barcelona. España.

dServicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario MútuaTerrasa. Consorcio Sanitario de Terrassa. Terrasa. Barcelona. España.

eServicio de Cirugía Pediátrica. Hospital Universitario MútuaTerrasa. Terrasa. Centro Hospitalario de Manresa. Fundación Althaia. Manresa. Barcelona. España.

Correspondence: S Fuentes. E-mail: sfuentes@mutuaterrassa.cat

Reference of this article: Fuentes Carretero S, Grande Moreillo C, Arranz Martí A, Salcedo Arroyo P, Robert Gil E, Martín Castillo ME, et al. Analysis of referrals for phimosis to specialist care: What happens next? . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:237-43. https://doi.org/10.60147/2d10de96

Published in Internet: 29-08-2025 - Visits: 4111

Abstract

Introduction: referrals for pediatric surgery consultation due to phimosis are relatively common. They generate a significant volume of patients that need to be seen at the hospital. As the current approach to the management of physiological asymptomatic phimosis is conservative, we set out to analyze the characteristics of these referrals and their outcomes.

Methods: we reviewed a random sample of referrals to pediatric surgery consultation for phimosis between 2019 and 2022. We analyzed patient characteristics, the reasons for referral and the outcomes of the consultation.

Results: the sample included a total of 392 referrals. The mean patient age was 5.8 years. Of this total, 40.6% were 4 years old or younger at the time of referral. Seventy-nine percent of de cases were asymptomatic. Twenty-four patients (6.2%) received a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans). Surgery was the approach selected in the initial visit in only 25% of the cases. Discharge or follow-up without active treatment were significantly more likely in children aged less than 6 years.

Conclusions: most children referred to pediatric surgery during the study period had asymptomatic physiological phimosis, and surgery was the selected approach in the initial consultation in only a quarter of them. In order to optimize resources and in adherence to current guidelines, we propose improving the education of families and health care professionals, ensuring adequate healthy foreskin care and conservative management of phimosis and limiting referrals for symptomatic cases or those that do not respond to conservative treatment.

Keywords

● Balanitis ● Pediatric urology ● PhimosisINTRODUCTION

Phimosis is one of the most frequent reasons for referral to pediatric surgery. The latest European urology guidelines emphasize that physiological phimosis can resolve spontaneously during childhood, so intervention with either topical corticosteroids or surgery is reserved for children with pathological or symptomatic phimosis.1-3

Studies in neighboring countries show rates of circumcision that exceed the estimated prevalence of phimosis for age.4,5 While discomfort or complications of the foreskin in adulthood are not desirable, there is a broad range of options for the management of physiological phimosis that does not resolve spontaneously before puberty.

Topical treatment with corticosteroid cream, which can be initiated at the primary care level, has a high efficacy rate.6 There are several equally effective regimens that can be used for first-line treatment of phimosis; ideally when the child is cooperative in the application of the cream.7 Even in cases of partial response, the reduction in the degree of phimosis allows for a less aggressive surgical approach, such as preputioplasty, rather than circumcision, if the parents agree. Thus, referrals to specialized care are essential in selected cases, although surgery is not always indicated: evaluation by a specialist may be necessary to inform and reassure the parents or to guide decision-making in complex cases or patients with suspected associated anomalies. Furthermore, in patients with pathological or symptomatic phimosis or with suspected balanitis xerotica obliterans, surgery should be considered from the outset.8 In such cases, early clinical diagnosis is essential. The appearance of the scarred foreskin differs distinctly from that of the healthy foreskin mucosa in physiological phimosis. The skin is thickened, whitish and may be cracked, and the mucosa does not protrude from the opening when attempting to retract the foreskin. It is important to begin treatment with topical corticosteroids and assess for glandular involvement and meatal stenosis, which may be associated with greater severity, in addition to a surgical evaluation.8

On the other hand, the clinical evaluation of children with phimosis in specialized care requires an in-person appointment at the referral hospital, which has some disadvantages, such as missed work and school, the cost associated with the use of the resource and eliciting concern in parents who visit the surgeon when young children with asymptomatic physiological phimosis probably do not require intervention.9

A study conducted in the United Kingdom in 2022 identified the restriction of referrals for phimosis surgery to cases of symptomatic or pathological phimosis or to older children in whom topical treatment has failed as a potential opportunity for improvement.9

The objective of our study was to analyze data on referrals to pediatric surgery for phimosis and preputial symptoms in our region to identify referral indications and subsequent outcomes, as well as to propose areas of improvement in the care pathway for these patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cross-sectional descriptive study. We analyzed a simple random sample of referrals from primary care to the department of pediatric surgery in our center due to phimosis in children aged 0 to 14 years between 2019 and 2022.

All codes and code extensions for phimosis in children aged 0 to 14 years referred from primary care to pediatric surgery were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were: concurrent referral for a different condition, referral for isolated frenulum breve, presence of congenital urogenital anomalies and referral for religious reasons.

We collected data on the following variables: demographic characteristics (age and history); phimosis-related variables (grade of phimosis according to Meuli classification, previous treatment, symptoms) and outcomes of the pediatric surgery consultation (treatment received, subsequent patient outcomes). Table 1 presents the Meuli classification.

| Table 1. Meuli phimosis scoring system | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Description |

| Grade 0 | Fully retractable prepuce without stenotic ring. No phimosis |

| Grade 1 | Fully retractable prepuce with stenotic ring in the shaft |

| Grade 2 | Partial retractability with partial exposure of the glans, stenotic ring |

| Grade 3 | Partial retractability with exposure of the meatus only |

| Grade 4 | No retractability |

The data were stored using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool.10,11 This web-based system enables the collection of research data, providing an interface as well as tools for data management and control.

We calculated the sample size required to estimate the proportion of surgical indication in referred patients, with an expected proportion of 20% of the total referrals in the past five years, for a precision of 3% and a confidence level of 95%. Assuming losses of 5%, we obtained a minimum sample size of 389 cases to review.

We grouped patients by age with the following rationale:

- Children aged less than 3 years, in which surgery is not indicated except in case of urgent necessity.

- Children aged 3 to 6 years among whom, based on the current evidence, the foreskin should be retractable in 90% of cases, but physiological phimosis may still resolve spontaneously.12,13

We combined these two groups for the analysis, as surgery is rarely indicated in either age interval.

- Children aged 7 to 10 years, in whom resolution of physiological phimosis is less likely and who have not started to undergo pubertal changes.

- Children aged 11 to 14 years who may have started puberty.

The statistical analysis was performed with the Stata/SE 13.0 software. We expressed quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages with the corresponding confidence intervals. We conducted a bivariate analysis to compare the proportions of the outcomes of interest in different age groups using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test, as applicable. We considered p-values of less than 0.05 statistically significant.

This study did not receive any external funding from any public or private organization.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our hospital (reference no. P/24-002).

RESULTS

Between 2019 and 2022, we received a total of 2486 referrals at our center, of which 803 (32.3%) met the inclusion criteria. The final sample included in the analysis consisted of 392 referrals.

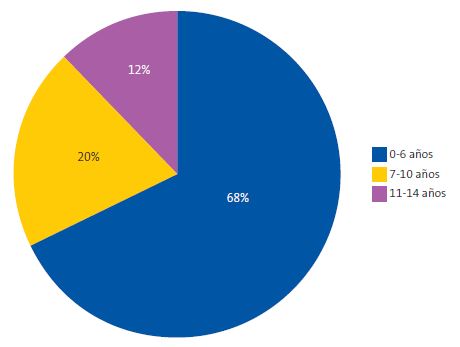

The mean (SD) age at the time of referral was 5.81 (± 3.12) years. Of this total, 72 patients were younger than 3 years (18.3%). When it came to the distribution of the sample based on the age groups established for the analysis, 68.1% were 0 to 6 years old, 20.2% were 7 to 10 years old and 11.7% were 11 to 14 years old. Figure 1 presents the distribution by age group.

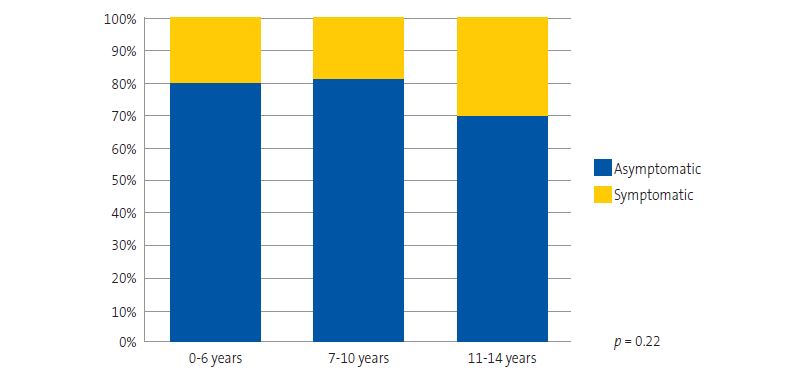

With regard to symptoms, 79.3% were asymptomatic. There was a higher percentage of symptomatic phimosis in the group aged 11 to 14 years (30.4% vs. 19.5% in the group aged 0-6 years and 19% in the group aged 7-10 years). These differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.22) (Figure 2). The most common clinical presentation in the overall sample was recurrent balanitis, followed by discomfort during erection. By age group, balanitis was the most common complaint in the 0-6 years group, accounting for 11% of cases in this age range. In the 7-10 years group, balanitis and erection discomfort were equally frequent (each occurring in 9% of patients), and in the 11-14 years group, the most common presentation was erection discomfort (25% of cases).

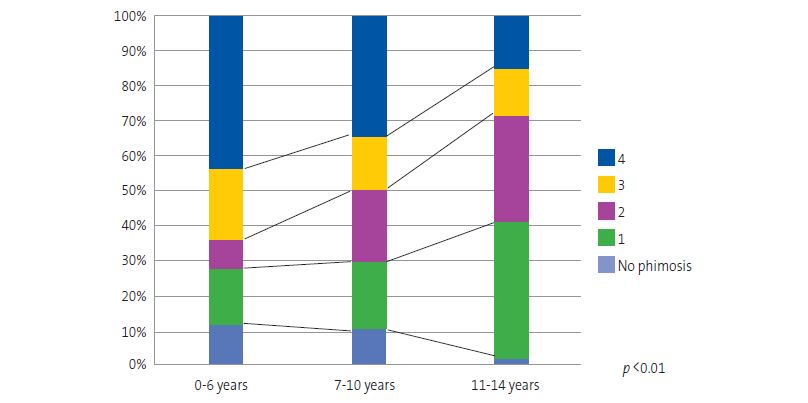

The most common grade of phimosis (Meuli scoring system) was grade 4 (completely closed foreskin with no retractability). The most prevalent grade of phimosis in children aged 0 to 6 years was grade 4 (43.8%), while in children aged 11 to 14 years it was grade 1 (39.1%), a difference that was statistically significant (p <0.01) (Figure 3).

Regarding prior treatment with topical corticosteroids, only 35.7% had received it before being referred to pediatric surgery, with no significant differences between age groups (p = 0.34).

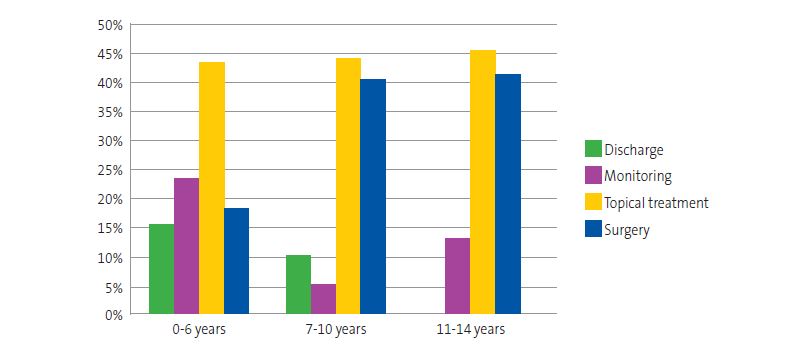

Figure 4 presents the approach to the management of phimosis after the pediatric surgery evaluation. Overall, surgery was the selected approach to management after the initial visit in only 25% of the evaluated children. Topical treatment was prescribed in 43.9% of children, while active treatment was not pursued in 30.9% (121 children), with the evaluation resulting in patient discharge or the scheduling of a future appointment for long-term follow-up. The probability of surgical intervention was higher in the older age groups (p < 0.01). The effectiveness of topical treatment was 65.3%.

Balanitis xerotica obliterans was diagnosed in 24 patients (6.5%), with a significantly higher incidence in the group aged 6 to 10 years (p = 0.01). In every case, the clinical suspicion was confirmed in the histological analysis of the specimen.

In children who underwent surgical intervention following failure of topical treatment, the mean (SD) age at the time of the procedure was 8.04 (± 2.9) years, and the mean (SD) time elapsed from the initial visit to the intervention was 8.97 (± 7.3) months (median, 7 months; IQR, 5-10).

A total of 134 cases were managed with surgery, with preputioplasty performed in 14.2% of cases and circumcision were in 85.8%.

DISCUSSION

Thanks to health care quality studies, we can assess whether scientific evidence is being applied in everyday practice.14 Our team set out to evaluate the care provided to children diagnosed with phimosis, as in recent years there has been a trend toward increasingly conservative management, as reflected in the international guidelines in the field.2,3

The management of phimosis has been evaluated in different care settings, including primary care and specialty care.15,16 Lastly, this study analyzed the link between these two settings to evaluate the entire care delivery process.

The most salient finding in our study was that surgery was the initially chosen approach in only 25% of referrals. Furthermore, in 30% of cases, patients were either discharged or scheduled for long-term follow-up without any active treatment or care recommendations. These results were consistent with those previously published in the United Kingdom, where efforts are underway to provide information to families and health care professionals on the care of the healthy foreskin.9 This requires establishment of management protocols and coordinated training of primary and hospital-based care providers.

Given that referrals place a significant burden in the health care system and entail an additional visit for parents—with the travel and possible worry or anxiety that it involves—we think it is important to reserve referral for patients with symptomatic phimosis or patients above a certain age who are still unable to retract the foreskin.

This is not to say that children should be left to reach puberty with phimosis that will cause them discomfort, as there is a window of opportunity to identify those cases where phimosis will resolve spontaneously and to operate on those where it will not, before pubertal changes begin.4

When we analyzed the data by age group, we saw that younger children, under 6 years of age, are more likely to be asymptomatic, even if they have severe phimosis; therefore, the percentage of surgical management in this age group was lower. Between the ages of 7 and 10, surgery is already contemplated, but topical treatment is usually attempted first, which does not excessively delay surgery if it is ultimately necessary, as the data shows.

It is worth noting that only one third of patients had received topical treatment before being referred for surgical consultation. In a past survey conducted in our region, most participating pediatricians reported that they attempted topical treatment before referring patients.15 We believe that topical treatment, when the child cooperates and participates in penis care or has symptoms, can be carried out safely and satisfactorily at the primary care level, with a success rate of up to 80%.6 In our case series, the success rate of topical treatment was 65%, and we believe that this low figure may be due to the fact that cases that responded to it at the primary care level did not reach the surgery clinic, whereas topical treatment is less likely to be successful in patients that are referred. Notwithstanding, attempting topical treatment again seems like an adequate option, provided that the child’s symptoms allow it. Even if it has been attempted before, there can be cases in which additional attempts achieve a response: children can be more cooperative when they are older (a boy aged 6 years is likely to engage more than one aged 3 years). We can also support families in its implementation and ultimately avoid surgery or lessen the severity of phimosis, so that conservative surgery, such as preputioplasty, can be offered instead of complete circumcision.

We must underscore the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. The incidence in our sample was of 6%, in line with global data, where it reaches 10% in some case series. In these cases, we consider that the patient can be referred to pediatric surgery for evaluation at the time of initiation of topical treatment.

In light of our findings, we plan to implement measures in our area to improve the information provided to parents and the knowledge of professionals, enabling us to support families in the care of the healthy foreskin, using the measures implemented in the United Kingdom as reference. We also consider that fluid communication between primary and specialty care is important in order to coordinate efforts in the implementation of current recommendations and improve overall quality of care.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the development of the published manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Wilcox D. Care of the uncircumcised penis in infants and children. In: UpToDate [online] [accessed 14/02/2025]. Available at www.uptodate.com/contents/care-of-the-uncircumcised-penis-in-infants-and-children

- Management Of Foreskin Conditions. Statement from the British Association of Paediatric Urologists on behalf of the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons and The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists [online] [accessed 14/02/2025]. Available at www.baps.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/MANAGEMENT-OF-FORESKIN-CONDITIONS.pdf

- European Association of Urology. Paediatric urology guideline. 2024 [online] [accessed 14/02/2025]. Available at https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology

- Shahid SK. Phimosis in children. ISRN Urol. 2012;2012:707329. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/707329

- Rickwood AM, Walker J. Is phimosis overdiagnosed in boys and are too many circumcisions performed in consequence? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71(5):275-7.

- Moreno G, Corbalán J, Peñaloza B, Pantoja T. Topical corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(9):CD008973. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008973.pub2

- Valdés Montejo I, Fuentes Carretero S, Pradillos Serna J, Ardela Díaz ED, Valladares Díez S, de Castro Vecino M. Éxito del tratamiento conservador de la fimosis, ¿la pauta de aplicación de corticoide tópico influye? Bol Pediatr. 2023;62(262):273-8.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric Lichen Sclerosus: A Review of the Epidemiology and Treatment Options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):593-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12615

- Sutton G, Fryer S, Rimmer G, Melling CV, Corbett HJ. Referrals from primary care with foreskin symptoms: Room for improvement. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58(2):266-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.10.046

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support, J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal l, et al. REDCap Consortium, The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners, J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin: A study of circumcision. BMJ 1949;2:1433-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1433

- Oster J. Further fate of the foreskin. Incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43(228):200-3. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.43.228.200

- Sullivan GA, Schäfer WLA, Raval MV, Johnson JK. Implementation science for quality improvement in pediatric surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2023;32(2):151282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2023.151282

- Robert Gil E, Fuentes Carretero S, Gatell Carbó A, Arranz Martí A, Vicente Sánchez N, Grande Moreillo C. Fimosis fisiológica, ¿la manejamos en Atención Primaria de acuerdo con las recomendaciones actuales? Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:21-6. https://doi.org/10.60147/3ab9a992

- Fuentes S, Vicente-Sánchez N, Martín-Castillo ME, Robert-Gil E, Arranz-Martí A, Grande-Moreillo C. A paradigm shift in the surgical treatment of phimosis in pediatric patients: Is practice aligned with current recommendations? Actas Urol Esp (English Ed). 2025;49(2):501710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuroe.2025.501710