Education in asthma. Assessment of knowledge about childhood asthma in primary care consultations

María Vegas Carróna, M.ª Teresa Asensi Monzób

aPediatra. CS Carranque. Málaga. España.

bPediatra. CS Serrería 1. Valencia. España.

Correspondence: M Vegas. E-mail: mvegas_91@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Vegas Carrón M, Asensi Monzó MT. Education in asthma. Assessment of knowledge about childhood asthma in primary care consultations. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2022;24:e93-e105.

Published in Internet: 12-04-2022 - Visits: 13430

Abstract

Objectives: to determine the level of knowledge about asthma of the relatives of asthmatic children followed in Primary Care consultations.

Material and methods: descriptive and cross-sectional study carried out through surveys sent by email and completed by relatives of asthmatic children followed up in primary care clinics. The surveys were conducted between November 2020 and March 2021. Asthma knowledge was assessed using the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ).

Results: 97 parents were surveyed (with a mean age of 39.73 years, 81.4% were mothers). The mean score obtained in the NAKQ was 19.97/31. We did not find a significant association between the NAKQ score and parental age, the number of asthmatic children, the use of preventive treatment, previous hospitalizations, the need for visits to the emergency room or the primary care centre in the event of asthma attacks, the history of vaccination against the flu in asthmatic children or being aware of the established risk groups for the flu vaccine. However, we found a statistically significant association between the NAKQ score and parental educational attainment (p = 0.002 <0.05) as well as the relation to the patient (mother or father) (p = 0.002 <0.05).

Conclusions: our respondents exhibited greater knowledge about asthma compared to other studies carried out in school or hospital settings. However, there were areas of deficient knowledge that could improve with the implementation of educational programmes at the primary care level, which would achieve an increase in the knowledge about asthma of the respondents and therefore, an improvement in their quality of life.

Keywords

● Asthma ● Asthma knowledge ● Education ● Primary health care ● The Newcastle Asthma Knowledge QuestionnaireINTRODUCTION

Asthma is the most common paediatric chronic disease in developed countries, with a substantial impact on individuals and families and in socioeconomic terms. It is the reason for much school absenteeism and is also one of the main causes of hospitalisation in children.1

As doctors we are increasingly aware of the importance of assessing the level of knowledge patients have about their diseases, particularly in the case of chronic pathologies, which require patients and their families to participate in their management. For this reason, considerable efforts have been devoted in recent years to educating asthmatic children and their families.2

Most studies show that educational interventions in addition to medical treatment of asthma are beneficial, as they improve the symptoms, increase knowledge about the disease, lead to the acquisition of skills and promote the participation of the family in managing the disease, thereby promoting adherence to treatment.2 For these reasons, the main asthma management guidelines recommend educational intervention as a cornerstone of asthma treatment.3 However, all this does not ensure a reduction in morbidity or an improvement in the quality of life of asthma patients unless it is accompanied by individualised action plans, periodic checkups and learning asthma self-management.4

Assessing the level of knowledge about asthma and its progression (known as "educational diagnosis") is considered an essential part of the asthma education process. For this purpose, we have several questionnaires, translated and validated in Spanish, including the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ), which has proved to be a valid instrument for evaluating patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge about asthma.2 The Spanish version is acceptable and culturally equivalent to the original and has a good reliability, validity and reproducibility.4

The objective of this study was to determine the level of knowledge about asthma and its management among relatives of asthmatic children managed at our primary care centre, using a questionnaire created and validated for this purpose.

As a secondary objective, we aimed to determine whether there is an association between relatives’ knowledge and the use of preventive treatment, previous hospitalisations, visits to emergency departments or to the primary care centre because of asthma exacerbations, and their influenza vaccination status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional observational study by means of self-completed questionnaires on knowledge of childhood asthma and its management. These questionnaires were sent by email (via Google Forms®) to relatives of asthmatic children managed in our PC clinic at the Carranque and Delicias primary care centres (Malaga, Spain). They were completed during the period from 23 November 2020 to 7 March 2021.

In this survey, we evaluated knowledge about asthma using the NAKQ translated into Spanish and validated by Praena et al.4 In addition, we collected a series of details to assess the patient’s clinical and family situation: age and sex of the patient and the relative, educational attainment of the relative, number of offspring with asthma, need for hospitalisation, visits to emergency department or health centre due to previous asthma exacerbations, preventive treatment used by the patient and influenza vaccination in the previous or current campaign.

Each question in the NAKQ scores 0 (incorrect) or 1 (correct), following the rating system of Praena, et al.4 The total score is obtained by adding up the scores assigned to each of the 31 questions that make up the questionnaire. Therefore, the final score can range between 0 and 31 points, and the higher the score obtained, the higher will be the degree of knowledge on asthma and its management.

Those considered eligible for this study were relatives of patients aged under 14 years with a previous medical diagnosis of asthma who consulted face to face or by telephone (because of the pandemic situation caused by COVID-19) for respiratory or other symptoms during the above-mentioned study period, when one of the researchers was present. The inclusion criteria were: relatives of legal age, with an appropriate command of Spanish and prior verbal consent to participate in the study, capable of understanding and filling in the questionnaire. Relatives who did not fulfil all the inclusion criteria mentioned were excluded. All of them were asked for their email address so that they could be sent the questionnaire via Google Forms®, provided that they had given their verbal consent in advance for use of the data.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the study variables and expressed the values as percentages of the total. In addition, for the numerical variables we calculated the mean, median, standard deviation and range.

The statistical analysis was carried out with the SPSS® program version 25.0. Differences with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used various tests to show the statistical association between the NAKQ test score quantitative variable and the other variables: the Pearson correlation coefficient for the quantitative variables, the t test (two categories) and analysis of variance (several categories) for the qualitative variables. We used the Mann-Whitney U test as a non-parametric test for data not meeting the assumption of normality.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

We sent 164 questionnaires and received 97 responses, which corresponded to a participation rate of 59.1%. The patients were 53 boys (54.6%) and 44 girls (45.4%) with a mean age of 6.8 years (standard deviation [SD] = 3.48; range 2-14).

In all, 81.4% of the questionnaires were completed by the mother, followed by 11.3% by the father, 5.2% by both and only 2.1% by another family member (mostly grandparents). The mean age of the respondents was 39.73 years (SD = 6.11; range 24–63). The predominant level of educational attainment among the respondents was a university education (35.1%) followed by vocational training (22.7%) and compulsory secondary education (16.5%). A total of 82.5% had only one child with asthma and 15.5% had more than one child with this condition; the mean number of asthmatic offspring was 1.21 (SD = 0.46; range 1-5).

The proportion of patients that had been admitted to hospital due to an asthma exacerbation was 13.4%. In 69.2% of these cases, the patient was hospitalised once, while in 30.8% it had been two or more times.

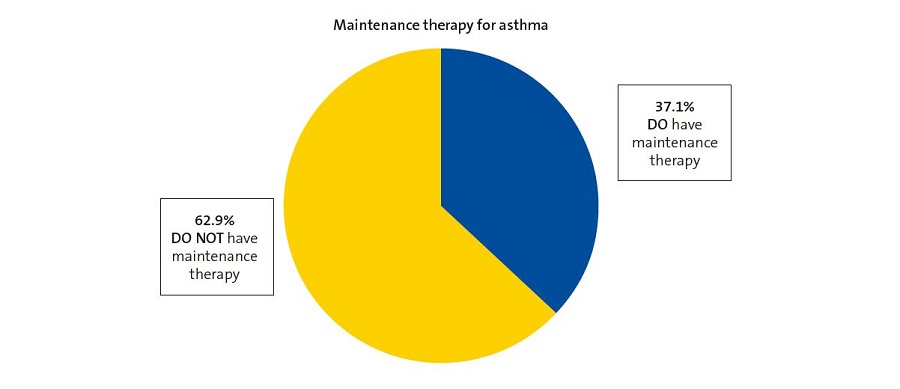

Of the surveyed children, 61.9% had visited an emergency department at least once because of an asthma attack, with a mean number of such visits of 2.74 (SD = 3.12; range 1-15). In addition, 52.6% of the patients had made an urgent visit to a primary care centre for an asthma attack. Only 10% of these said they had done so on one occasion, compared to 90% who had made 2 or more visits for this reason. Therefore, we found that respondents brought their children to hospital emergency departments more frequently than to primary care centres in the event of an asthma exacerbation (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1. Comparative pie charts for visits made by respondents with their children after the diagnosis of asthma to hospital emergency departments and to primary care centres in the event of an asthma exacerbation. |

|---|

|

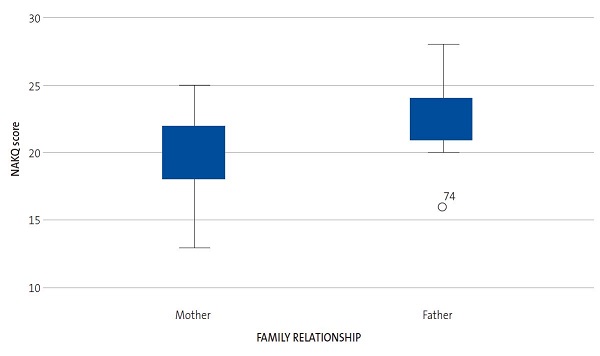

As regards maintenance therapy, 62.9% of the patients had not been prescribed maintenance medication, whereas 37.1% had (Fig. 2), mainly inhaled corticosteroids (43.9%), followed by a combination of long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (22%), antileukotrienes (17.1%) and a combination of antileukotrienes and inhaled corticosteroids (17.1%).

NEWCASTLE ASTHMA KNOWLEDGE QUESTIONNAIRE

The mean score obtained in the NAKQ was 19.97 (SD = 2.66; range 13-28). Table 1 shows the percentage of correct answers for each of the 31 items in the questionnaire.

| Table 1. Percentages of correct answers to each of the 31 items in the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Question in the NAKQ | Number of correct answers/total | % correct |

| 1. What are the three main symptoms of asthma? (Complete in words) | 24/97 | 25% |

| 2. One in ten children will have asthma at some time during their childhood. (True/False) | 79/97 | 81.4% |

| 3. Children with asthma have abnormally sensitive air passages in their lungs. (T/F) | 70/97 | 72.2% |

| 4. If one child in a family has asthma then all his/her brothers and sisters are almost certain to have asthma as well. (T/F) | 87/97 | 89.7% |

| 5. Most children with asthma have an increase in mucus when they drink cow’s milk. (T/F) | 69/97 | 71.1% |

| 6. Write down all the things you know that cause an asthma attack (sometimes called trigger factors). (Complete in words) | 8/97 | 8% |

| 7. During an attack of asthma, the wheeze may be due to muscles tightening in the wall of the air passages in the lungs. (T/F) | 59/97 | 60.8% |

| 8. During an attack of asthma, the wheeze may be due to swelling in the lining of the air passages in the lungs. (T/F) | 88/97 | 90.7% |

| 9. Asthma damages the heart. (T/F) | 69/97 | 71.1% |

| 10. Write down two asthma treatments (medicines) which are taken every day on a regular basis to prevent attacks of asthma from occurring. (Complete in words) | 15/97 | 15% |

| 11. Which three asthma treatments (drugs) are useful during an attack of asthma? (Complete in words) | 34/97 | 35% |

| 12. Antibiotics are an important part of treatment for most children with asthma. (T/F) | 73/97 | 75.3% |

| 13. Most children with asthma should not consume dairy products. (T/F) | 84/97 | 86.6% |

| 14. Allergy shots cure asthma. (T/F) | 86/97 | 88.7% |

| 15. If a person dies from an asthma attack, this usually means that the final attack must have begun so quickly that there was no time to start any treatment. (T/F) | 54/97 | 55.7% |

| 16. People with asthma usually have "nervous problems". (T/F) | 71/97 | 73.2% |

| 17. Asthma is infectious (i.e., you can catch it from another person). (T/F) | 97/97 | 100% |

| 18. Inhaled medications for asthma (such as the Ventolin® or Terbasmin® inhalers) have fewer side effects than tablets and syrups. (T/F) | 32/97 | 33% |

| 19. Short courses of oral corticosteroids (such as Estilsona®, Dacortin® or prednisone) usually cause significant side effects. (T/F) | 77/97 | 79.4% |

| 20. Some asthma treatments (such as Ventolin®) damage the heart. (T/F) | 75/97 | 77.3% |

| 21. A five-year-old child has an asthma attack and takes two puffs from a Ventolin® inhaler (a metered-dose inhaler). After five minutes there is no improvement. Give some reasons why this might have happened. (Complete in words) | 9/97 | 9% |

| 22. During an asthma attack that is being treated at home, your child needs to use an inhaler with a space chamber (or mask) every two hours. The child is getting better, but after two hours he/she is having difficulty breathing. Since the child is not getting worse, it is OK to continue giving the treatment every two hours. (T/F) | 32/97 | 33% |

| 23. Write down ways of helping to prevent attacks of asthma during exercise. (Complete in words) | 8/97 | 8% |

| 24. Children with asthma become addicted to their asthma medications. (T/F) | 78/97 | 80.4% |

| 25. Swimming is the only suitable exercise for asthmatics. (T/F) | 88/97 | 90.7% |

| 26. Parental smoking may make the child’s asthma worse. (T/F) | 94/97 | 96.9% |

| 27. With appropriate treatment, most children with asthma should lead a normal life with no restrictions on activity. (T/F) | 94/97 | 96.9% |

| 28. The best way to measure the severity of a child’s asthma is for the doctor to listen to the child’s chest. (T/F) | 27/97 | 27.8% |

| 29. Asthma is usually more of a problem at night than during the day. (T/F) | 71/97 | 73.2% |

| 30. Most children with asthma will have stunted growth. (T/F) | 86/97 | 88.7% |

| 31. Children with frequent asthma symptoms should take preventive drugs. (T/F) | 77/97 | 79.4% |

- General knowledge of asthma

Only 25% of respondents were able to correctly list the three main symptoms of an asthma attack. In a higher percentage of cases (52%), they named up to two symptoms, but the marking rules for the NAKQ require that in order for the answer to be valid, all three symptoms have to be listed.

On other questions, 81.4% knew the prevalence of asthma, 72.2% knew that children with asthma have abnormally sensitive airways and 71.1% stated that asthma does not damage the heart. Most respondents (96.9%) knew that them being smokers could worsen their children’s asthma and 73.2% knew that asthma is more problematic at night than during the day. However, 72.2% of parents thought that the best way to measure the severity of asthma is for the doctor to perform chest auscultation.

- Acute asthma attack

Only 8% of respondents correctly identified the three main triggers of asthma attacks (exercise, allergens and colds), although 47% identified one trigger and 25% identified two. A total of 60.8% indicated that wheezing may be due to bronchoconstriction, and 90.7% responded that it was due to inflammation of the bronchial wall.

As for treatment of an acute attack, only 35% were able to correctly name two useful treatments for an asthma exacerbation and 39% correctly identified one treatment. One of the most common errors was including budesonide as a medication in this group. In addition, only 8% knew two ways to prevent an asthma attack during exercise, while half of those surveyed (50%) did not correctly identify any form of prevention.

As for the side effects of drugs, 79.4% knew that short courses of oral corticosteroids do not cause significant side effects and 77.3% knew that salbutamol does not damage the heart, but only 33% knew that inhaled medications have fewer side effects than oral ones.

With regard to the question on how to manage an asthma attack that does not improve after a dose of salbutamol (Ventolin), only 9% were able to identify two correct interventions, while more than half (59% of cases) were unable to state any correct course of action.

- Maintenance therapy

Most respondents (75.3% of cases) knew that antibiotics are not an essential part of treatment and that allergy shots are not a definitive treatment for asthma (88.7% of cases).

In the questions related to maintenance therapy, only 15% of respondents were capable of identifying two maintenance medications, although more than half (57%) were able to identify at least one of them, with both generic names and active principles considered valid. Despite this, 79.4% of respondents considered that children with frequent asthma symptoms should take preventive treatment, and 96.9% stated that most children can lead a normal life with no restrictions by following appropriate treatment.

- Erroneous beliefs

Regarding the relationship between asthma and allergy to the proteins in cow’s milk, most of those surveyed (71.1%) knew that their children do not have an increase in mucus when they drink cow’s milk and therefore 86.6% of them assumed that they could consume dairy products.

Moreover, all respondents (100%) stated that asthma is not infectious, and 73.2% correctly answered that children with asthma do not have “nervous” problems. In addition, 80.4% knew that children with asthma do not become addicted to their medications and 88.7% stated that asthma does not stunt growth.

VACCINATION AGAINST INFLUENZA

When relatives were asked about their knowledge on the annual influenza vaccination campaign, 78.4% stated that they knew their child belonged to one of the risk groups eligible for receiving the vaccine funded by the National Health System. However, only 6% of the relatives were able to correctly identify three of the risk groups for vaccination, while 12% identified two groups, 34% one group and 47% were not capable of identifying any risk group.

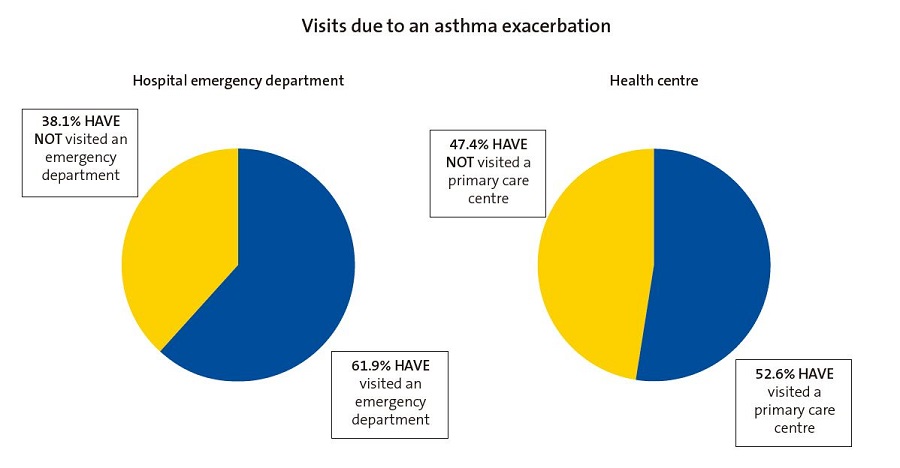

The influenza vaccine had been administered to 81.3% of asthmatic children in the current vaccination campaign (2020–2021), whereas in last’s years campaign it was only given to 53.6%, so there was a 27.7% increase in those vaccinated in the current campaign compared to the previous one (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3. Pie charts showing asthmatic children vaccinated against influenza during the 2020/2021 vaccination campaign compared to the 2019/2020 campaign |

|---|

|

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In the statistical analysis, we did not find a significant association between the NAKQ score and parental age (p = 0.995 >0.05) or the number of asthmatic offspring (p = 0.788 >0.05) (Pearson correlation).

Moreover, there was no significant association between the NAKQ score and the use of preventive treatment (p = 0.381 >0.05), previous hospitalizations (p = 0.055 >0.05), or the need to visit the emergency department (p = 0.436 >0.05) or primary care centre (p = 0.267 >0.05) in the event of an asthma exacerbation; all of these were assessed by means of the t test for independent samples.

We also found no statistically significant associations between the NAKQ score and previous vaccination of asthmatic children, either in the current 2020-2021 vaccination campaign (p = 0.161 >0.05) or in the previous 2019-2020 campaign (p = 0.105 >0.05), nor between the NAKQ score and knowing which risk groups benefit from influenza vaccination (p = 0.660 >0.05), assessed by means of the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

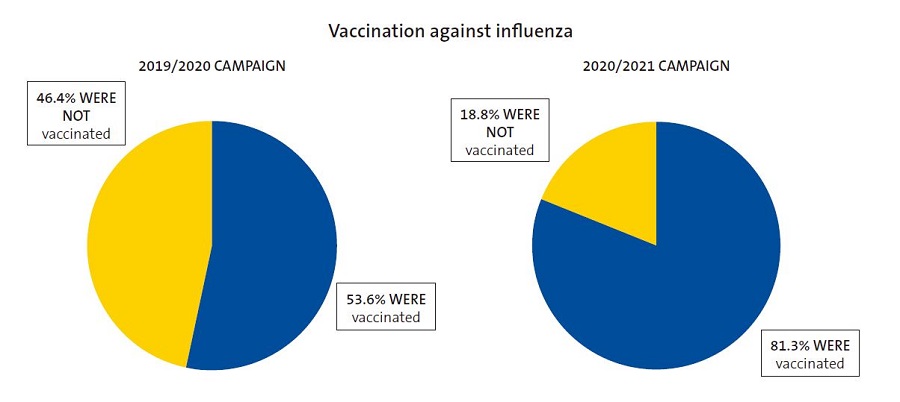

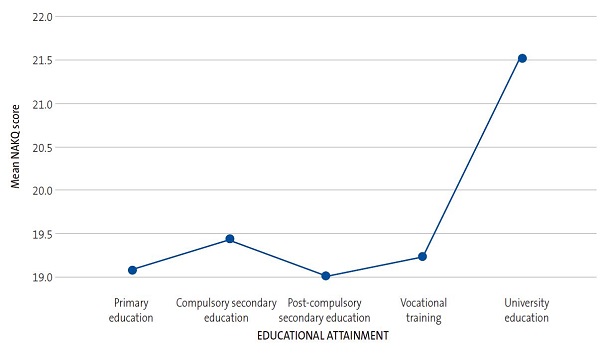

However, we found a statistically significant association (p = 0.002 <0.05) between the NAKQ score and the educational attainment of the respondent, assessed by one-factor ANOVA (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 4).

| Table 2. One-factor analysis of variance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAKQ score | |||||

| Sum of the squares | df | Quadratic mean | F | p-value | |

| Between groups | 115.356 | 4 | 28.839 | 4.644 | 0.002 |

| Within groups | 552.644 | 89 | 6.209 | ||

| Total | 668.000 | 93 | |||

| Table 3. Descriptive analysis of the mean NAKQ score by relatives’ level of educational attainment, where a higher mean NAKQ score (21.53) is observed in the group with higher education compared to the mean NAKQ score in the other groups according to relatives’ level of educational attainment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive statistics | ||||||||

| NAKQ score | ||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | SE | 95% confidence interval for the mean | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| Primary education | 14 | 19.07 | 3.100 | 0.829 | 17.28 | 20.86 | 16 | 28 |

| Compulsory secondary education | 16 | 19.44 | 1.965 | 0.491 | 18.39 | 20.48 | 17 | 23 |

| Post-compulsory secondary education | 11 | 19.00 | 3.000 | 0.905 | 16.98 | 21.02 | 13 | 23 |

| Vocational training | 21 | 19.24 | 2.567 | 0.560 | 18.07 | 20.41 | 14 | 23 |

| Higher education | 32 | 21.53 | 2.185 | 0.386 | 20.74 | 22.32 | 17 | 25 |

| Total | 94 | 20.00 | 2.680 | 0.276 | 19.45 | 20.55 | 13 | 28 |

| Figure 4. Comparative line graph of mean NAKQ scores based on the educational attainment of the relative |

|---|

|

We also confirmed, by the t test for independent samples, that there were statistically significant differences (t = −3.12, p = 0.002 <0.05) in the questionnaire score based on the relationship of the respondent to the child (mother or father) (Tables 4 and 5, Fig. 5).

| Table 4. Student t-test for independent samples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levene test for equality of variances | t-test for equal means | ||||||||

| NAKQ score | F | P | t | df | P (2-tailed) | Mean diff. | SE diff. | 95% confidence interval of the difference | |

| Lower | Higher | ||||||||

| Assuming equal variances | 0.326 | 0.569 | -3.122 | 86 | 0.002 | -2,654 | 0.850 | -4.343 | -0.964 |

| Not assuming equal variances | -2.526 | 10.37 | 0.029 | -2.654 | 1.051 | -4.984 | -0.324 | ||

| Table 5. Descriptive analysis of mean NAKQ score according to type of family relationship, confirming that the mean NAKQ score is higher in the group of fathers (22.5) compared to the group of mothers (19.50), always bearing in mind the small sample size of the group of fathers (n = 10). | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group statistics | |||||

| Family relationship | n | Mean | SD | SEM | |

| NAKQ score | Mother | 78 | 19.85 | 2.439 | 0.276 |

| Father | 10 | 22.50 | 3.206 | 1.014 | |

DISCUSSION

There are several studies in Spain that use the NAKQ translated and adapted to Spanish by Praena et al.4 to assess the knowledge on asthma in parents, teachers or asthmatic adolescents.2-9

The mean level of knowledge in the sample under study can be considered intermediate, since the score obtained in the NAKQ (19.97 ± 2.66) was higher than that reached by the group of people with little knowledge of asthma (16.84 ± 2.56) in the validation study for the Spanish version of the NAKQ conducted by Praena et al.,4 but lower compared to the scores obtained by the group with considerable knowledge (23 ± 2.94) in the same study. Moreover, the NAKQ score in our study was also higher compared to the scores achieved by the low-asthma knowledge group (13.0) in the original validation study for the NAKQ by Fitzclarence and Henry in 1990,5 but inferior to the scores of the high-knowledge group in that study (25.3).

In our study, conducted with relatives of asthmatic children managed in PC clinics, we observed that the NAKQ score was clearly superior compared to those attained in other studies of parents of asthmatic children in hospital settings, such as those by García-Luzardo et al.2 in a paediatric emergency department (with an NAKQ score of 16.14 ± 2.92) and by Leonardo Cabello et al.3 in an outpatient paediatric pulmonology clinic (with an NAKQ score of 18.5 ± 3.7).

In addition, the NAKQ score in our study was higher than those obtained by teachers (17.90 ± 3.1), asthmatic adolescents (17.24 ± 2.7) and non-asthmatic adolescents (16.23 ± 2.8) in Praena et al.’s study on asthma in several schools,6 and also higher than the score of 16.0 ± 4.8 obtained by teachers in the Estudio sobre Asma en los Centros Escolares Españoles (EACEE – Study on Asthma in Spanish Schools).7

As regards the NAKQ scores obtained by the relatives of asthmatic children admitted to hospitals due to exacerbations, they were also lower, as reflected in the study carried out in Australia by Henry, et al.,8 with an NAKQ score of 18.3 in the group of children with several prior admissions and 17.2 points in those being hospitalised for the first time. A lower NAKQ score (15.5 points) was also observed in the study conducted in Malaysia by Fadzil and Norzila9 in 2002.

Thus, it is noteworthy that our respondents, surveyed in the PC setting, showed a greater level of knowledge (with higher NAKQ scores) compared to other studies performed in hospital settings with parents of asthmatic children, since it would be reasonable to assume that these hospital patients have more longstanding or severe asthma and therefore to expect them to have a higher degree of knowledge of the disease. The higher level of knowledge shown in PC clinics might be explained by a higher level of trust and rapport in the doctor-patient relationship, in addition to greater accessibility, allowing asthmatic children and their relatives to express their uncertainties about asthma and its management and have them resolved quickly and effectively in a more comfortable and familiar setting than that which might exist in an emergency department or hospital wards.

Several previous studies found statistically significant associations between parental asthma knowledge level and other variables, such as parental educational attainment. One is the study by Fadzil and Norzila,9 cited above, which concluded that the level of knowledge on asthma was higher in the group of parents of higher socioeconomic status, which the authors thought could be related to a higher educational attainment in that group. Moreover, the same study found a statistically significant association between parental asthma knowledge and the use of steroid therapy for maintenance, especially at high doses (p = 0.03 <0.05); we were unable to corroborate these findings in our study because the NAKQ score obtained in the sample was not associated with their children’s maintenance therapy (p = 0.88 >0.05). As in our study, Fadzil and Norzila9 did not find significant differences in the results based on parental age or the previous history of hospital admission. The study conducted in Australia by Henry et al. also concludes that the degree of knowledge of parents of asthmatic children was greater in the high socioeconomic level group and in non-smokers, but that the history of previous hospital admissions did not modify the level of knowledge. Similarly, in our survey we did not find a significant association between the level of knowledge on asthma and the need for hospitalisation or visits to an emergency department or PC centre in the event of an exacerbation.

We ought to mention that there are studies that have found that the number of visits to emergency departments for asthma exacerbations may be reduced by an increase in the parents’ knowledge through educational programmes, as was the case of the study carried out by Wesseldine et al.,10 in which an educational intervention on asthma achieved a significant reduction in hospital readmissions and in visits to emergency departments or PC centres for asthma attacks. Similarly, the meta-analysis performed by Coffman et al.11 concluded that providing asthma education reduces visits to emergency departments and the mean length of stay for asthma patients, although the authors stated that it did not change the probability of admission or the number of urgent visits to the PC doctor.

Another point that should be emphasised in our study is the statistically significant association found between the level of knowledge of asthma and the relationship of the respondent to the child (p = 0.02 <0.05), with a clearly higher mean NAKQ score in the group of fathers compared to the group of mothers, a result that should be analysed further given the small number of fathers in the sample. We were unable to corroborate this finding with other similar studies, as there are no previous analyses of the association between these variables.

It is important to consider that in our study there were gaps in asthma knowledge in the surveyed sample, and therefore areas which could be improved. We ought to highlight the result obtained in question 10 on asthma maintenance therapy, where only 15% of respondents were able to correctly identify two preventive drugs, a percentage that was considerably lower compared to those found in the study in emergency departments by García Luzardo et al.2 (26.6%) and the study in pulmonology wards by Leonardo Cabello, et al.3 (43%). Although asthma education is the responsibility of all healthcare professionals at any level of care and of schools, in principle it should be delivered mainly in the PC setting, given its closeness and accessibility. However, the published data show that the education provided by PC paediatricians is insufficient.12 Despite the fact that information (anatomical and physiological knowledge, triggers, practical demonstration of inhaler technique) is frequently conveyed, there are deficiencies in the provision of written action plans and in education in self-management.12 Many patients are seen at the clinic on demand, as opposed to scheduled appointments, which is more suitable for developing an educational programme. Nurses, who should play an essential role in educational activities in coordination with other health professionals, are frequently not involved in the care of asthmatic children.12 All this represents deficiencies in organisational aspects such as time allocation, participation and coordination among professionals, giving rise to inadequate quality of care, where it is not possible to develop effective educational programmes enabling relatives to increase their knowledge on asthma control and maintenance therapy. This sometimes leads to lack of knowledge, non-adherence or abandonment of treatment by asthmatic children and their families, as can be seen in question 10.

This does not occur in relation to asthma exacerbations (question 11), as 35% of respondents were able to correctly identify two drugs used for management of asthma attacks, a percentage only slightly lower than the one found in the study in pulmonology wards by Leonardo Cabello et al.3 (39.2%) but slightly higher compared to the study of emergency departments by García Luzardo et al.2 (31.9%). This may be due to the accessibility and closeness of PC providers, which leads many parents and relatives to attend primary care centres on numerous occasions when their children have asthma attacks, to confirm the diagnosis and ensure that they are treating them correctly. Introducing improvements in educational programmes (for instance, to reinforce the use of written action plans) would therefore produce obvious long-term benefits for our patients, in addition to improving their quality of life.

Finally, with regard to influenza vaccination, we should highlight the increase in the number of asthmatic children vaccinated in 2020-2021 compared to the previous season. This increase could be related to the COVID-19 pandemic in the earlier campaign, since worry and uncertainty in the population as to whether both respiratory viruses might trigger a higher number of asthma attacks or make them more severe made families of asthmatic children very sensitive to the importance of influenza vaccination in that group.

As for the limitations of our study, we must point out the fact that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the associated lockdown, which posed a major difficulty for obtaining the sample by reducing both the incidence of asthma-related morbidity and the number of face-to-face visits for asthma in PC. In addition, some families had difficulty using online applications and therefore completing the questionnaires sent by email, which caused a fairly significant reduction in the sample size. All this made it difficult to subsequently develop an educational programme with our asthmatic patients and their relatives to improve their NAKQ scores and therefore their knowledge about asthma.

CONCLUSIONS

We think it is interesting to contribute to the literature the results obtained with the NAKQ to assess the knowledge of asthma in an extensive sample of relatives of asthmatic children managed at the PC level, as the NAKQ has been used in Spain primarily to evaluate knowledge in educators,1,6,7 emergency departments2 or outpatient pulmonology clinics,3 and there are only a few studies at the international level10,11 conducted in samples of relatives of asthmatic children managed in PC clinics and hospitals (emergency and inpatient care).

Our main conclusion is that, compared to other studies conducted in school or hospital settings, surveyed individuals had a greater level of knowledge on asthma (reflected in a higher NAKQ score).

We recognise that there are numerous deficiencies in the population under study, which should be improved by implementing quality educational programmes at the PC level, such as scheduling appointments devoted specifically to asthma for each patient or group educational workshops for several families.

In addition, the use of new technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic has motivated us to consider new ways of educating asthma patients and their families using online resources and materials, such as instructional videos on the main aspects of the disease that could be sent by email to these families.

Our hypothesis is that a subsequent educational intervention would not only lead to an increase in the NAKQ score and knowledge on asthma among participants in future studies, but in the long term it would make it possible to reduce both the number of urgent visits and the direct and indirect use of healthcare resources which this entails, as well as achieving an improvement in asthma self-management and therefore in our patients’ quality of life.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

EACEE: Estudio sobre el Asma en los Centros Escolares Españoles (Study on Asthma in Spanish Schools) · NAKQ: Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire · PC: primary care · SD: standard deviation.

REFERENCES

- Fierro Urturi A, Acebes Puertas R, Córdoba Romero A, del Amo Ramos S, Sanz Fernández M. Impacto de una intervención educativa sobre asma en los profesores de Educación Infantil y Primaria de una zona básica de salud. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020; 22:353-60.

- García Luzardo MR, Aguilar Fernández AJ, Rodríguez Calcines N, Pavlovic Nesic S. Conocimientos acerca del asma de los padres de niños asmáticos que acuden a un servicio de urgencias. Acta Pediatr Esp .2012;70:196-203.

- Leonardo Cabello MT, Oceja-Setien E, García Higuera l, Cabero MJ, Pérez Belmonte E, Gómez-Acebo I. Evaluación de los conocimientos paternos sobre asma con el Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2013;15:117-26.

- Praena Crespo M, Lora Espinosa A, Aquino Llinares N, Sánchez Sánchez AM, Jiménez Cortés A. Versión española del NAKQ. Adaptación transcultural y análisis de fiabilidad y validez. An Pediatr. 2009;70:209-17.

- Fitzclarence CA, Henry RL. Validation of an asthma knowledge questionnaire. J Paediatr Child Health. 1990;26:200-4.

- Praena Crespo M, Fernández Truan JC, Aquino Llinares N, Murillo Fuentes A, Sánchez Sánchez A, Gálvez González J, et al. Situación de los conocimientos, las actitudes y la calidad de vida en asma de adolescentes y profesorado. Necesidad de educar en los centros de enseñanza. An Pediatr. 2012;77:226-35.

- López-Silvarrey Varela A. Estudio sobre el asma en los centros escolares españoles (EACEE) 2009-2010. A Coruña. In: Fundación María José Jove; 2011 [online] [accessed 18/04/2021]. Available at: www.fundacionmariajosejove.org/media/upload/files/Maqueta_final_publicacin_resultados_Estudio_Asma_Nacional_FMJJ_FBBVA_en_11.pdf

- Henry RL, Cooper DM, Halliday JA. Parental asthma knowledge: its association with readmission of children to hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 1995;31:95-8.

- Fadzil A, Norzila MZ. Parental asthma knowledge. Med J Malaysia. 2002;57:474-81.

- Wesseldine L, McCarthy P, Silverman M. Structured discharge procedure for children admitted to hospital with acute asthma: a randomised controlled trial of nursing practice. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:110-14.

- Coffman JM, Cabana MD, Halpin HA, Yelin EH. Effects of asthma education on children’s use of acute care services: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2008;121:575-86.

- Rueda Esteban S. Asma en el niño y adolescente (controversias): Atención Primaria versus Atención Hospitalaria. A favor del manejo en el hospital. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2014;16:17-27.