Vol. 23 - Num. 89

Original Papers

Analysis of 37 cases of leishmaniasis in children, diagnosed in a region of Valencia, Spain

Yolanda Mañes Jiméneza, Gema M.ª Pedrón Marzala

aServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Lluís Alcanyís. Játiva. Valencia. España.

Reference of this article: Mañes Jiménez Y, Pedrón Marzal GM. Analysis of 37 cases of leishmaniasis in children, diagnosed in a region of Valencia, Spain. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2021;23:33-41.

Published in Internet: 17-03-2021 - Visits: 26051

Abstract

Introduction: the aim of the study was to analyse the increase in the incidence of leishmaniasis observed in the Xativa-Ontinyent health area of the Valencian Community, Spain, and to determine the clinical profile of this disease, analysing the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and response to treatment.

Methods: we conducted a retrospective epidemiological study in children aged less than 15 years given a diagnosis of visceral or cutaneous leishmaniasis at the Hospital Lluís Alcanyís in Xàtiva between January 2009 and December 2018.

Results: the study included 37 cases of leishmaniasis, 15 visceral and 22 cutaneous. The median age was 17 months in cases of visceral leishmaniasis and 2 years and 8 months in cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis. At the time of diagnosis, all patients with visceral leishmaniasis presented with fever, anaemia and splenomegaly. Cutaneous leishmaniasis manifested with erythematous papules or plaques. The diagnosis was confirmed by direct visualization of amastigotes in lesion biopsy samples in 68% of cases, and in 32% by PCR of a skin scrape or lesion biopsy. In patients with visceral leishmaniasis, testing of the bone marrow aspirate was positive in 25% and the PCR test of peripheral blood was positive in 100%. All patients with visceral leishmaniasis were treated with liposomal amphotericin B, with resolution of fever within 72 hours. Ninety-one percent of patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis were treated with meglumine antimony, and all had favourable outcomes.

Conclusions: we confirmed the increase in the incidence of leishmaniasis in the years under study and analysed the clinical profile of paediatric cases of leishmaniasis, which differs from the patterns observed in adults, observing a good response to treatment.

Keywords

● Child ● Cutaneous leishmaniasis ● Diagnosis ● Leishmania ● Visceral leishmaniasisINTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis refers to a group of parasitic diseases spread worldwide with different clinical forms. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) o kala-azar is the most severe form, with a fatality rate of nearly 100% if untreated, and localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL) usually has a benign course.1 They are caused by a protozoan in the Leishmania genus (Trypanosomatidae family) transmitted by the bite of infected phlebotomine sandflies.2

Leishmaniasis is endemic in 88 countries in the tropical and temperate regions of the world.3,4 In Spain, the incidence of leishmaniasis based on hospital admission data is of 1.5 per 100 000 inhabitants/year in children under 5 years and 0.13 per 100 000 inhabitants/year in children aged 5-14 years.4,5 In the Mediterranean region, the endemic pathogen associated with this disease is L. infantum.1

Visceral leishmaniasis is characterised by fever, anorexia, weight loss, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and abnormal findings in blood tests, such as anaemia, leukocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia and hypergammaglobulinemia.

When an infected vector bites a host, it inoculates between 10 and 100 promastigotes that are phagocyted by the mononuclear phagocyte system, thereby transforming into amastigotes, which are obligate intracellular parasites of mononuclear phagocytes. Infected macrophages spread the infection through the reticuloendothelial system, with parasites accumulating in the liver, spleen and bone marrow.3

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis can present as a single or several cutaneous lesions following an incubation period (lasting from 2 weeks to 2 months) appearing as erythematous macules that progress to papules with a hard, indurated, hyperaemic and sometimes itchy base usually located in areas where the skin is exposed. They may undergo ulceration over a period of weeks or months, usually into a painless ulcer with well-defined borders. There is no suppuration except in case of bacterial superinfection. Some lesions resolve spontaneously, but ulcerated lesions may become chronic and eventually cause deformities.6,7

The diagnosis of VL is confirmed by visualization of amastigotes in the microscopic examination of a bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood sample or by visualization of promastigotes in a culture sample.7 Molecular techniques (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) have proven more sensitive than traditional techniques.8,9 The detection of specific antibodies is simple but has limitations, as their levels continue to be detectable for years following the cure and do not allow discrimination of acute infection, past infection or reinfection.1 The definitive diagnosis of la LCL is made with the same techniques, except with skin scraping or biopsy samples obtained from the lesions.

At present, the first-line treatment is a short course of liposomal amphotericin B (LAB) for VL and a pentavalent antimonial (meglumine antimoniate) delivered intramuscularly, intravenously or through intralesional infiltration for LCL.

Leishmaniasis has been a reportable disease in Spain since 1982.1

Our health care area (Xàtiva-Ontinyent) has the highest incidence of leishmaniasis in the Valencian Community (2017). Thus, the aim of our study was to investigate the increase in the incidence of leishmaniasis observed in our area and establish a clinical profile by analysing the clinical presentation, diagnosis and response to treatment of identified cases.

SAMPLE AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective epidemiological study by reviewing the health records of patients aged less than 15 years given a diagnosis of VL or LCL between January 2009 and December 2018 at the Hospital Lluís Alcanyís de Xàtiva, a secondary care hospital in the county of La Costera (Health Care Area 14, Xàtiva-Ontinyent) in the province of Valencia, with a catchment population of 194 682 inhabitants of who 27 049 are aged less than 15 years (demographic data from December 2018).

The county of La Costera is located in a sub-humid area with a warm climate and a high relative humidity but scant precipitation with large areas of vegetation and several swamps.

In our hospital patients with leishmaniasis undergo diagnosis and treatment in the departments of Paediatrics and Dermatology. We completed our review by documenting cases confirmed by the Department of Microbiology and the Department of Pathological Anatomy, as cutaneous cases are most frequently managed at the outpatient level without requiring hospital admission.

The inclusion criteria were age less than 15 years and a definitive diagnosis of leishmaniasis. We defined diagnosis of VL as the presence of compatible clinical manifestations and positive results of diagnostic tests: direct microscopic visualization of the parasite or positive PCR in a bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood sample. Clinical suspicion of LCL was confirmed by direct visualization of the parasite or positive PCR in a skin scrape or biopsy sample. We excluded patients with incomplete health records.

For cases of VL, we collected data on the age, sex, duration in days of fever at diagnosis (fever defined as an axillary temperature ≥ 38 °C) and presence of hepatomegaly and of splenomegaly, and for cases of LCL we collected data on the age, sex, duration of disease and location and number of lesions.

For cases of VL, we collected the results of the complete blood count, white blood cell differential and blood chemistry panel, serological tests and Leishmania antigen detection in urine. We defined anaemia as a haemoglobin concentration more than 2 standard deviations below the mean for age, leukopenia as a total white blood cell count of less than 4 × 103/μl and thrombocytopenia as a platelet count equal to or less than 150 × 103/μl. We also documented the methods used for diagnosis.

We documented the drug used for treatment with its dose, duration, clinical response, associated adverse events and the followup of the patient for up to 6 months by the Department of Paediatrics for all cases of VL. We defined cure as a sustained favourable clinical response with resolution of fever and normalization of abnormal test results following initiation of treatment, along with evidence of progressive resolution of visceromegaly in the followup. We defined relapse as the recurrence of signs and symptoms associated with detection of Leishmania spp after completion of medical treatment.

We conducted a descriptive study with calculation of the mean/median, standard deviation and contingency tables with the software SPSS version 26.0.

RESULTS

A total of 37 patients received a diagnosis of leishmaniasis, 15 of VL and 22 of LCL. Twenty-five patients were male (67%) and 12 female (33%), and all were immunocompetent.

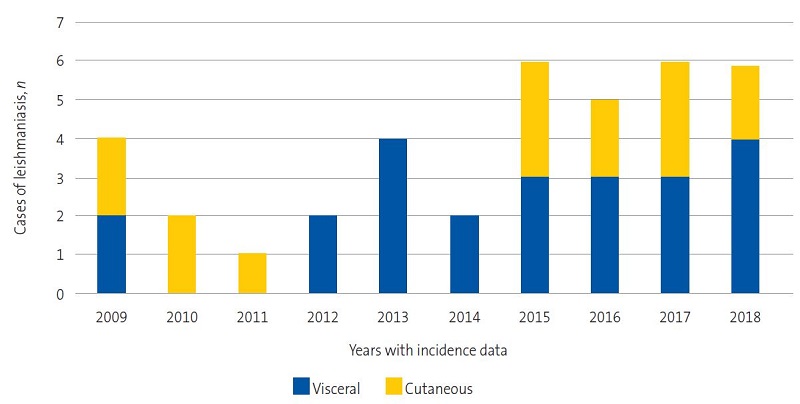

Figure 1 shows the increase in the frequency of documented cases of VL and LCL.

| Figure 1. Incidence of leishmaniasis; years 1982-2017*; distribution in Valencian Community and Spain |

|---|

|

The mean age was 10.7 months in patients with VL (range: 3 months-9 years) and 22.4 months in patients with LCL (range: 6 months-14 years).

In VL cases, the most common presentation that was the reason for admission was poor general health, with 100% of these patients presenting with fever with a median time elapsed from onset to diagnosis of 12 days (range: 5-30 days). Hepatomegaly was detected in 80% and splenomegaly in 100% (Table 1).

| Table 1. Clinical manifestations at diagnosis of cases of visceral leishmaniasis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical manifestations at diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis (n = 15) | n | % | Median | Range | |

| Fever (days) | 15 | 100% | |||

| Time elapsed from onset to admission (days) | 12 | 5 | 30 | ||

| Splenomegaly/size (cm*) | 15 | 100% | 3 | 1.5 | 10 |

| Hepatomegaly/size (cm*) | 12 | 80% | 1.75 | 1 | 6 |

All patients presented with anaemia (Table 2). Five patients required transfusion of packed red blood cells due to low haemoglobin concentrations associated with poor general health, weight faltering, pallor, heart murmur and tachycardia. Leukopenia was detected at admission in 40% of cases and thrombocytopenia in 66.6%. Five patients (33.3%) had pancytopenia at the time of diagnosis.

| Table 2. Laboratory features at diagnosis in cases of visceral leishmaniasis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory features at diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis | Median | Range | Patients with abnormal findings | % | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl)n = 15 patients | 8.5 | 6 | 11.3 | 15 patients (anaemia) | 100% |

| White blood cells/µln = 15 patients | 4900 | 3140 | 12 600 | 6 patients (leukopenia) | 40% |

| Platelets/µln = 15 patients | 123 000 | 73 000 | 188 000 | 10 patients (thrombocytopenia) | 66.6% |

| CRP (mg/l)n = 13 patients | 50 | 6 | 242.4 | 4 patients (CPR ≥80) | 30.7% |

| AST/GOT (UI/l)n = 14 patients | 175 | 104 | 274 | 6 patients (≥3 times ULN) | 42.8% |

| ALT/GPT (UI/l)n = 14 patients | 163.5 | 90 | 40% | 4 patients (≥3 times ULN) | 28.5% |

The median serum level of C-reactive protein (CPR, measured in 13 patients) was 50 mg/l (range: 6-242.4 mg/l), with a value ≥80 mg/l in 4 patients (30.7%). We observed elevation of liver enzymes, with levels 3 times the upper level of normal of AST/GOT in 6 patients (42.8%) and of ALT/GPT in 4 patients (28.5%) (Table 2).

Cases of LCL presented with an erythematous plaque or papule of varying size, with more developed lesions presenting central ulceration without suppuration. The median duration of the lesions was 6 months (range: 2-18 months). Most cases (75%) were complicated on account of the location of lesions in the face, eyelid, helix or fingers and, in a lesser percentage of patients (13.3%), failure of local treatment after 2-3 months of therapy.10

All lesions were located in areas of exposed skin, mainly in the face (63%). Two patients had lesions in the helix of the right ear, a rare location that is difficult to treat and with a tendency to chronicity. Two patients (10%) had more than one cutaneous lesion.

The diagnosis of LCL was confirmed by visualization of amastigotes in 15 patients (68%) and by molecular methods (PRC test in a skin scrape or biopsy sample) in 7 patients (32%).

Tables 3 and 4 present the methods used to confirm the diagnosis of VL. We ought to highlight that in 2 patients (cases 2 and 8) treatment was initiated based solely on positive results of serological testing, with titres greater than 1/40 measured by indirect immunofluorescence, in addition to the presence of compatible manifestations. Two patients had positive results in 2 diagnostic tests.

| Table 3. Methods used for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis visceral | |||||

| Patients | Year of diagnosis | BMO | PB smear | PCR SP | Serology (IIF) |

| 1 | 2009 | Not performed | Leishmania spp. | Not performed | Positive |

| 2 | 2009 | Negative | Not performed | Not performed | Positive |

| 3 | 2010 | Not performed | Leishmania spp. | Not performed | Negative |

| 4 | 2010 | Positive | Leishmania spp. | Not performed | Positive |

| 5 | 2011 | Not performed | Leishmania spp. | Positive | Positive |

| 6 | 2015 | Positive | Negative | Not performed | Negative |

| 7 | 2015 | Not performed | Leishmania spp. | Not performed | Positive |

| 8 | 2015 | Not performed | Not performed | Not performed | Positive |

| 9 | 2016 | Not performed | Not performed | Positive | Positive |

| 10 | 2016 | Not performed | Leishmania spp. | Not performed | Positive |

| 11 | 2017 | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 12 | 2017 | Not performed | Not performed | Positive | Positive |

| 13 | 2017 | Not performed | Not performed | Positive | Not performed |

| 14 | 2018 | Not performed | Not performed | Positive | Positive |

| 15 | 2018 | Not performed | Not performed | Positive | Positive |

| Table 4. Methods used for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic test | n | Positive | Negative | Sensitivity |

| BMA examination | 4 | 2 | 2 | 50% |

| PB smear | 8 | 6 | 2 | 75% |

| PB PCR | 7 | 7 | 0 | 100% |

| Serology (IIF) | 14 | 11 | 3 | 78.50% |

| Leishmania urine antigen detection | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0% |

None of the patients required intensive care.

Cases of VL were treated with LAB (AmBisome) administered intravenously at doses of 3-5 mg/kg/day, with administration of a daily dose from days 1 to 5 and a 6th dose on day 10 (2 patients in the early years under study followed a different regimen: the first received 3 mg/kg/day for 5 days with additional doses on days 14 and 21, the second received 3 mg/kg/day on days 1, 5, 10, 14 and 21). All received a total cumulative dose of LAB of 20 mg/kg, with resolution of fever within 72 hours from initiation. None of the patients experienced adverse events.

Only 1 patient experience recurrence with fever, night-time irritability and mild hepatosplenomegaly 3 months after completion of treatment, with detection by PCR of Leishmania infantum in a bone marrow aspirate sample. The patient underwent a second course of LAB at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day administered intravenously for 10 consecutive days, without further recurrences at the time of the 12-month followup.

When it came to the management of LCL, 91% of patients underwent intralesional infiltration of meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime). A watchful waiting approach was taken in a patient aged 12 months, who had a favourable outcome with spontaneous resolution of the lesion. Another patient, aged 2 years and with lesions in the face and lower lip, was treated with LAB. Seven patients (31.8%) required 1 or 2 infiltrations and 11 (50%) 3 to 5 infiltration. Only 2 patients, aged 2 and 5 years, with lesions in the cheek, had a more protracted course of disease that required combined therapy with imiquimod followed by infiltrations of Glucantime for a total duration of treatment of 12 months. All patients had favourable outcomes, and none required surgical removal of the lesion.

DISCUSSION

Based on data from the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network, there has been an increase in the regions where leishmaniasis is endemic worldwide accompanied by an increase in the reported cases of this disease. According to the World Health Organization, Spain is considered among the countries in Europe with the greatest burden of disease.11 The global prevalence is estimated at 12 to 14 million affected individuals, with an incidence of 2 million new cases per year, of which 1.5 are cutaneous and 500 000 visceral.

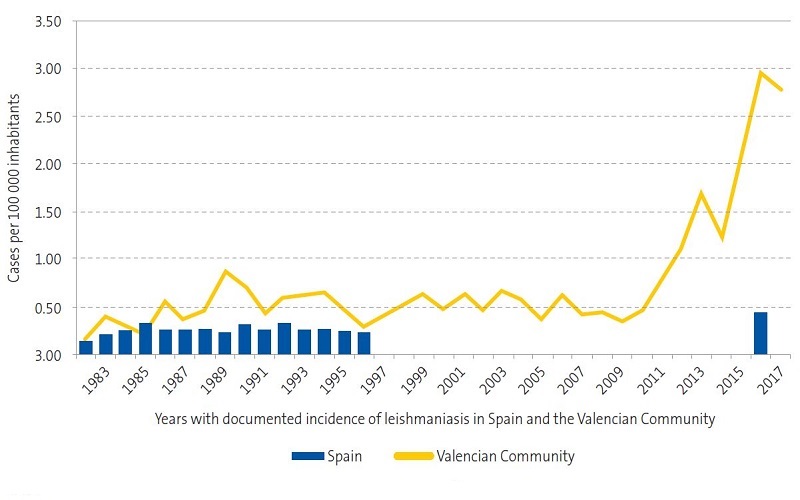

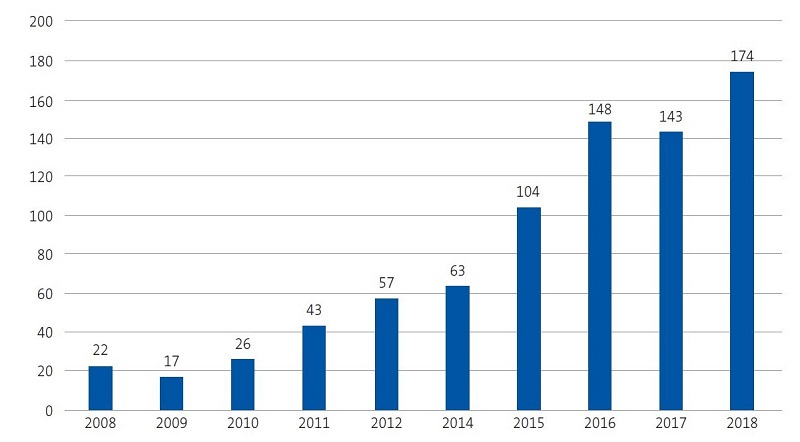

In 2017, the incidence of leishmaniasis in the Valencian Community was of 2.9 cases per 100 000 inhabitants per year in the general population.12 The most recent epidemiological reports published in our region by the Department of Public Health12,13 show an exponential increase in cases between 2010 and 2017 (Figures 1 and 2), which was consistent with our findings, as we observed an increasing trend in the last 4 years (Figure 3).

| Figure 2. Temporal trends in the incidence of leishmaniasis in the Valencian Community in the past decade |

|---|

|

In agreement with the previous literature,4,11,14-16 we found that VL was much more frequent in children, especially in infants, compared to the adult population. Still, LCL is the most frequent presentation in the paediatric population.17 The predominance of VL in infants may be explained by the immaturity of the immune system.

The typical presenting symptoms in our patients with VL, which were fever, splenomegaly and anaemia, were consistent with the current literature5,11,15 and are the basis for suspecting the diagnosis in infants.

In most cases, the lesions associated with LCL were found in the head and neck, in agreement with the findings of Dunya et al.17 in a study conducted in Syria in 168 patients with LCL, in which this location was most frequent (57.1%), particularly the cheek. A study conducted by Roth-Damas et al. in a geographical area of the Valencian Community15 also found that most cases involved single lesions (61%) and, as occurred in our study, 2 patients with lesions in the earlobe.

We found significant changes in the methods used for confirmation of leishmaniasis through the years, especially for cases of VL. Early cases underwent serological tests with confirmation by direct visualization of the parasite with a microscope. In recent years, less invasive diagnostic tests have been developed, such as PCR testing of peripheral blood, which has proven more sensitive than direct observation.8,14 It offers a sensitivity of 92-98% and a specificity of 100%.17 In 2 cases, the definitive diagnosis was made based on the results of serological testing alone, as was also described in the study by Ramos et al.11.

In the past, antimony compounds were used for first-line treatment of VL, although the long duration of these regimens, which required hospitalization, their potential toxicity and the relatively high frequency of treatment failure led to the investigation of alternatives like LAB, whose use was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration in 1997. All of our patients with VL were treated with LAB, which was well tolerated.

All patients with VL had favourable outcomes save for 1 patient that experienced a relapse (6.6%), a proportion that was similar to the one reported by Prieto Tato et al., who detected recurrence in 11 patients.5

Patients with LCL were treated with intralesional injection of glucantime, with addition of imiquimod in 2 cases. In our series, a patient aged 2 years with a lesion of 2 months’ duration located in the facies-lower lip required treatment with LAB, an alternative that was already documented in the study by Del Rosal T et al.7 All patients had favourable outcomes with full resolution of the lesion.

CONCLUSIONS

- There has been an increase in the incidence of leishmaniasis in the last 4 years.

- In endemic areas, the differential diagnosis of an infant presenting with prolonged fever, hepatosplenomegaly and decreased counts of one or more blood cell lineages should include VL.

- LCL should be suspected in patients with a long-lasting erythematous plaque or papule in an exposed area of the skin.

- Molecular diagnostic methods based on PCR are less aggressive and more sensitive. Patients with VL exhibit a good response with favourable outcomes to treatment with LAB.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

LAB: liposomal amphotericin B · LCL: cutaneous localized leishmaniasis · PCR: polymerase chain reaction · VL: visceral leishmaniasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank everyone involved in the study for their collaboration.

REFERENCES

- Cano Portero R, Sierra Moros MJ, Tello Anchuela O. Protocolos de la Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Madrid: Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica; 2013.

- Leishmaniasis. In: World Health Organization 04/12/2020]. Available at https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Melby PC. Leishmaniasis (Leishmania). In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St Geme JW, Schor NF (eds.). Nelson Tratado de Pediatría. 20th Barcelona: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 1241-5.

- Errasti I, Aracil FJ. Zoonosis en Pediatría. In: Guerrero-Fdez J, Cartón A, Barreda A, Menéndez J, Ruíz J (eds.). Manual de diagnóstico y terapéutica en Pediatría. 6th edition. Madrid: Panamericana; 2018. pp. 1625-8.

- Prieto LM, La Orden E, Guillén S, Salcedo E, García C, García-Bermejo I, et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la leishmaniasis visceral infantil. An Pediatr (Barc). 2010;72:347-51.

- Valcárcel Y, Bastero R, Anegón M, González S, Gil A. Epidemiología de los ingresos hospitalarios por leishmaniasis en España (1999-2003). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2008;26:278-81.

- Del Rosal T, Baquero-Artigao F, Gómez C, García MJ, de Lucas R. Tratamiento de la leishmaniasis cutanea con anfotericina B liposomal. An Pediatr (Barc). 2010;73:101-2.

- Cruz I, Chicharro C, Nieto J, Bailo B, Cañavate C, Figueras MC, et al. Comparison of new diagnostic tools for management of pediatric Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2343-7.

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC. Molecular diagnosis of leishmaniasis: current status and future applications. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:21-5.

- Aronson N. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Treatment. In: UpToDate [online] [accessed 03/03/2021]. Available at www.uptodate.com/contents/cutaneous-leishmaniasis-treatment?search=leishmaniacutaneaniñosclasificacion&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~149&usage_type=default&display_rank=2

- Ramos JM, Clavijo A, Moral L, Gavilán C, Salvador T, González de Dios J. Epidemiological and clinical features of visceral leishmaniasis in children in Alicante Province, Spain. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2018;38:203-8.

- Servicio de Vigilancia y Control Epidemiológico; Subdirección General de Epidemiología, Vigilancia de la Salud y Sanidad Ambiental; Dirección General de Salud Pública; Conselleria de Sanitat Universal y Salut Pública. Informe Enfermedades trasmitidas por vectores Comunitat Valenciana. Vigilancia Epidemiológica Año 2017. In: Conselleria de Sanitat Universal y Salut Pública [online] [accessed 03/03/2021]. Available at www.sp.san.gva.es/DgspPortal/docs/informe_etv_CV2017.pdf

- Servicio de Vigilancia y Control Epidemiológico; Subdirección General de Epidemiología, Vigilancia de la Salud y Sanidad Ambiental; Dirección General de Salud Pública; Conselleria de Sanitat Universal y Salut Pública. Informe Enfermedades trasmitidas por vectores Comunitat Valenciana. Vigilancia Epidemiológica Año 2018. Valencia: Conselleria de Sanitat Universal y Salut Pública [online] [accessed 03/03/2021]. Available at www.sp.san.gva.es/DgspPortal/docs/informe_etv_CV2018.pdf

- Cascio A, Calattini S, Colomba C, Scalamogna C, Galazzi M, Pizzuto M, et al. Polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis and prognosis of Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis in immunocompetent children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e27.

- Roth-Damas P, Sempere-Manuel M, Mialaret-Lahiguera A, Fernández-García C, Gil-Tomas JJ, Colomina-Rodríguez J, et al. Brote comunitario de leishmaniasis cutánea en la comarca de La Ribera: a propósito de las medidas de Salud Pública. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:338-43.

- Palomares Gimeno MJ, Segura Navas L, Renau Solaz S, Bueno Claros D. Leishmaniasis cutáneo-visceral, sospecharla para diagnosticarla. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:49-53.

- Dunya G, Habib R, Moukarbel R V, Khalifeh I. Head and neck cutaneous leishmania: clinical characteristics, microscopic features and molecular analysis in a cohort of 168 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3819-26.