Vol. 22 - Num. 87

Original Papers

How have children experienced the confinement due to coronavirus?

Pedro J. Gorrotxategi Gorrotxategia, M.ª Esther Serrano Povedab, Francisco Javier Garrido Torrecillasc, Marta Esther Vázquez Fernándezd, Marianna Mambié Menéndeze, M.ª Teresa Cenarro Guerrerof

aPediatra. CS Pasaia San Pedro. Pasajes. Guipúzcoa. España. Vocalía de Comunicación de la AEPap

bPediatra. CS Miguel Servet. Valencia. España. Directora de la web Familia y Salud de la AEPap

cPediatra. EBAP-UCG Churriana de la Vega. Granada. España.

dPediatra. CS Arturo Eyries. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España. Grupo Educación para la Salud de la AEPap

ePediatra. CS Escorxador. Palma de Mallorca. Baleares. España. Presidenta de la ApapIB

fPediatra. CS Sagasta-Ruiseñores. Zaragoza. España. Vocalía de Comunicación de la AEPap

Correspondence: PJ Gorrotxategi. E-mail: pedro.gorrotxa@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Gorrotxategi Gorrotxategi PJ, Serrano Poveda ME, Garrido Torrecillas FJ, Vázquez Fernández ME, Mambié Menéndez M, Cenarro Guerrero MT. How have children experienced the confinement due to coronavirus? Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:273-81.

Published in Internet: 16-09-2020 - Visits: 20355

Abstract

Introduction: children have feelings and experiences that they cannot or will not express and that may manifest through their drawings and imagination. The Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics, AEPap) wanted to explore how children have experienced the confinement.

Material and methods: we organized a contest through the Family and Health website. The study population consisted of children residing anywhere in Spain aged 3 to 16 years. The works submitted were drawings, micro stories or micro videos.

Results: we received 53 works from children in different autonomous communities and gave 5 awards. The elements featured most frequently were the coronavirus, figures of children indoors, a rainbow in the clouds and health care professionals. Some of the subjects expressed in the works were boredom, missing grandparents and friends, trust in health care professionals, a positive perception of the change in life in the family, the improvement in environmental pollution and a positive view that everything will turn out well.

Conclusions: the results obtained in this study suggest a generalized optimism and allow us to conclude that drawings, stories and videos are a useful tool to analyze the perception of this population in risk situations. We also ought to highlight the interest of primary care paediatricians in how children have experienced the confinement imposed due to the coronavirus pandemic and raise awareness that children’s drawings should be carefully studied.

Keywords

● Contest ● Coronavirus ● Drawings ● Lockdown ● Stories ● VideosINTRODUCTION

After the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the coronavirus pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Spanish government declared a “state of alert” in March 14,1 which, as established in article 9, suspended in-person education in every school at every level of education, leading to the confinement of children in their homes.

There is no way to establish how children have experienced the confinement imposed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Each child is different from all others, and their answers and perceptions are also different.

The Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics, AEPap) has set out to assess the experience of children during confinement. To this end, the association organised a contest through its website for families, Familia y Salud. The contest was defined as follows in the call for entries2:

In the current health and social crisis that is affecting every part of our society and the daily routines of families, the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPap) and its website, Web Familia y salud, want to offer you the opportunity to share your experiences and feelings as well as a source of creative entertainment during this period. We would like to know how our children and adolescents are experiencing the confinement at home imposed due to coronavirus.

Age: 3 to 16 years. “How are you experiencing the stay-at-home order due to coronavirus?”. Now that we all need to stay home, what could be better than to draw or write a few sentences expressing what is happening to us and how we are experiencing it as a family?

The submitted works will present creative ideas in the following formats: micro story, micro video or drawing. We propose that you submit creative works to enter our contest: “Be creative, at home during coronavirus”.

Works can be submitted in Spanish, Euskara, Catalan or Galician.

We will accept submissions until the day we are allowed to leave our homes freely because the coronavirus crisis is improving.

We chose drawings to assess how children have experienced this period because their drawings reflect their feelings and emotions. In some instances, children express feelings and experiences in drawings that they do not know how to describe otherwise, or that they are afraid to share. The aspects that need to be considered include the characteristics of the stroke, how the drawing fits in space, the situation depicted and the colours used. Thus, the drawing filling the entire space suggests that the child is extroverted and confident and feels safe. If only part of the space is used, it suggests shyness and introversion. Placing the drawing in the middle of the page is associated with the present time and suggests absence of worry or feelings of insecurity. The left side represents the past, something that is remembered with fondness or that is a source of concern. The right side represents the future. The top represents thought, imagination and curiosity. The bottom represents material needs. As for colour, use of many different colours usually expresses joy and a sense of security, while use of the same colour in different drawings may suggest insecurity and lack of confidence. Mixing colours, drawing with some colours over others, may suggest irritability.3

This way of assessing how children perceive this subject could be included in the field of qualitative research. It has been developed in our field due to its importance and usefulness in exploring human dimensions and to assess behaviours, concerns, attitudes values, expectations and interactions between individuals in relation to a subject or phenomenon of interest.4

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants: children residing anywhere in Spain aged 3 to 16 years.

Works: drawings, short stories and brief videos.

Format of submissions: drawings as PNG/JPG files; micro stories with a maximum character count of 280 as Word files (could be submitted in any of the official languages in Spain: Spanish, Catalan, Euskara or Galician); brief videos with a maximum duration of 1 minute as MP4 files. The files were submitted by electronic mail.

Data requested for registration: full name, age, phone number, electronic mail address and contest category. Submission start date: March 22, 2020. We announced that the contest would end once the confinement order was lifted. Since confinement ended on April 26, as announced in the BOE of the day before,5 we last day we accepted submissions was May 4.

Originally a single award was to be granted per category (story, video, drawing), but since we received a substantially larger amount of drawings, we decided to add a classification by age group in this category taking into account both the number of participants of each age and the stages of development in drawing.6

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the number of works submitted by category and the characteristics of the participants.

| Table 1. Works entered in the contest by category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Frequency (n = 53) | Mean age | Male/female (%) |

| Drawing | 32 | 8.25 years | 25/75% |

| Story* | 12 | 9.33 years | 25/75% |

| Video | 9 | 10.11 years | 33/66% |

The autonomous communities represented by the entries were Andalusia, Extremadura, Valencian Community, Basque Country, Madrid, Galicia, Castilla y Leon, Aragon and Balearic Islands.

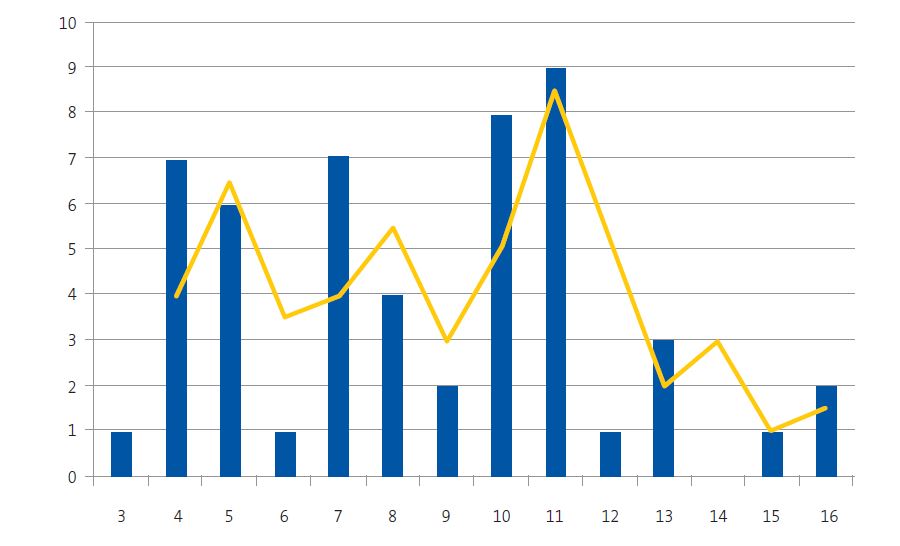

Fig. 1 presents the age distribution of the children that entered the contest.

Analysis of drawing contents

The elements featured most frequently were:

- The coronavirus (12 drawings), whose frequent depiction in the press has made its form known to children. It is usually represented as a large shape, at times with a mouth and teeth. It may be featured next to a child or outside a home while the children remain indoors. The size suggests that children find it scary, large and dangerous, and in some images the virus has an angry expression.

- Second in frequency were figures of children. In some cases they were depicted inside the home, in others, playing, and yet in others along with a representation of coronavirus. The same ideas recurred: fear of being next to the virus and safety in staying in the house.

- Third in frequency, appearing in 6 instances, was the “together, we can do it” icon, a rainbow between 2 clouds, which has gained considerable popularity during the confinement imposed to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

- The fourth most frequent element was the health care worker (in 3 drawings), either drawn as figures or alluded to with words of encouragement for them.

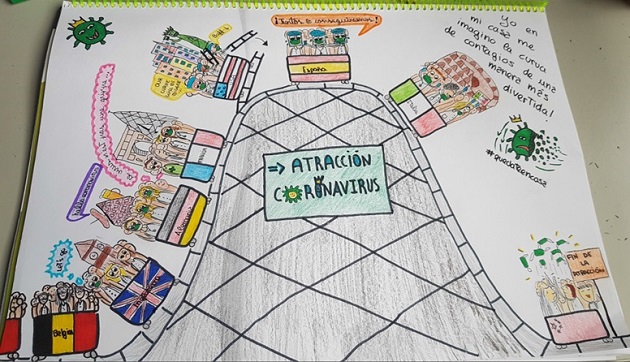

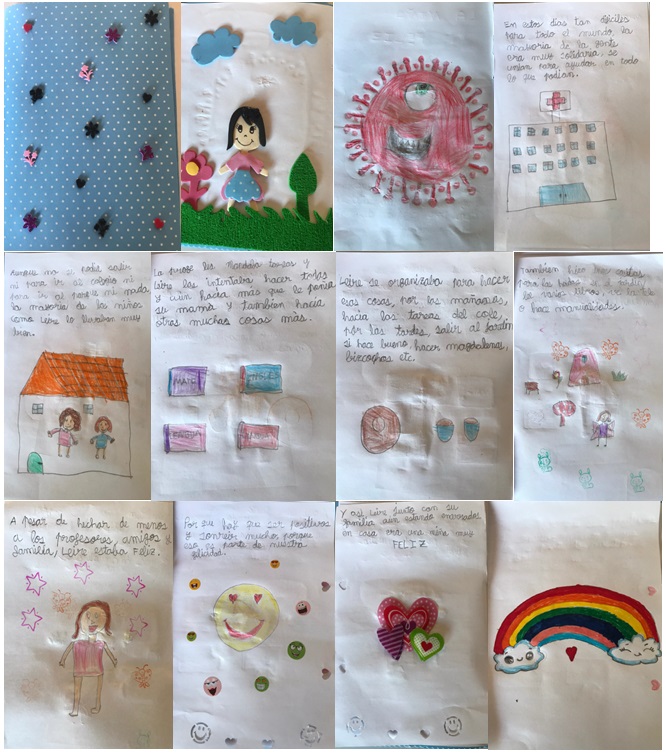

Figs. 2, 3 and 4 show the drawings that received the awards in each of the 3 age categories.7

The drawing in Fig. 4 stands out due to its originality and optimism. The girl depicted the curve of coronavirus cases as a theme park ride, specifically as a roller coaster along which different countries and people, represented by their flags and famous monuments, go through different stages of the pandemic until getting back to the starting point, when face masks are finally thrown in the air.

Analysis of story contents

The stories reflected both the optimism of some children (“everything will turn out well”) and the boredom they felt at times. They perceived the inability to see their friends and grandparents negatively, and the change in domestic life positively, in that they spent more time with their parents and siblings. They discussed how they did homework, how they played, baked, etc. As for the positive impact, 2 contestants mentioned that the confinement is resulting in a decrease in la environmental pollution and in 3 that this means that less people get ill. Others gave free rein to their imagination and told stories about spirits or other subjects that had nothing to do with coronavirus or confinement but made an entertaining read.

Fig. 5 presents the story that won the award, which included the contents mentioned above.

Analysis of videos

The themes were quite varied. Some children showed how they played at home, others discussed the advantages of staying home as if they were being featured on TV, or explained how to use alcohol-based hand sanitizers or other means of protection, underscored the important role of health care workers in the fight against disease or narrated a story or presented an animation explaining how a child deals with confinement.

The video that received the award (Fig. 6) is actually a series of short videos in which the main characters, a friendly boy aged 6 years and his father, appear in costume and perform with considerable wit and creativity.

| Figure 6. Micro video award (Jesús F., 6 years, Badajoz). |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

We are aware that our study allowed us to assess the perceptions of a limited number of children and that the selection was not random but based on voluntary participation in a contest, so our conclusions cannot be extrapolated to the entire paediatric population, but apply only to this particular group of children.

The Universidad del País Vasco (UPV) has carried out a study of similar characteristics.8 They carried out a survey by electronic mail, requesting families that they ask children to draw 2 scenarios, what they did during the confinement at home and what they missed. They also requested that the children answered 2 questions: “How are you feeling?” and “What feelings do you have in this situation of lockdown or confinement?”.

The first part of that study, with the drawings depicting confinement, would correspond to our proposal for the drawing contest, and the second part about how they are experiencing the confinement, to our proposal for the story contest.

When it came to the drawings, the study of the UPV found that the youngest children reflected the various crafts they did with other household members. On the other hand, when it came to the activities, people and settings that they missed, the most frequent were meeting other relatives like cousins and grandparents and playing with friends out of doors. Along the same lines, children also frequently expressed a need for air and sunshine and depicted rainbows, among other features, as elements associated with the world outside the home.

When it came to the answers given to the questions posed by the UPV, a boy aged 4 years, for example, said: “It is a virus that we don’t really know. We have to stay home and win over it because it is bad. In the street, doctors, which are heroes and brave, are going to defeat it and that is why we come out to the balcony every day to clap for them”.

Thus, it is apparent that both the images and textual answers given in the study of the UPV are quite similar to the submissions we received for our contest, corroborating that this experience involved a fear of the virus, at the same time as the perception of doing something positive against the virus and yearning to meet friends and relatives.

Several institutions, interest groups and psychologists have alerted of the potential negative impact of confinement in children. For instance, the Analysis, Intervention and Applied Therapy Research Group (AITANA) of the Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (Alicante) considered that the state of alert declared due to COVID-19 and all its repercussions constitute a novel constellation of stressors that differ from previously existing ones and that may cause psychological disturbances in the paediatric population similar to those caused by already known stressors.9

In a press release of May 8, Save The Children10 warned that social isolation measures imposed due to COVID-19 may cause long-lasting psychological disorders in children, such as depression. It reported the results of a survey it had carried out that found concerning figures for mental health disorders in many children of both sexes. For instance, in Finland, 7 out of 10 children in the survey reported anxiety and 55% fatigue. In the United Kingdom, nearly 60% of children that responded to the survey were worried about the possibility of a family member getting the disease, and 3 out of 10 children in Germany were concerned about not being able to finish the school year. A fourth of the respondents in the United States had anxiety. In Spain, where Save The Children interviewed nearly 2000 low-income families at the beginning of the pandemic, 4 out of 10 households reported an increase in the level of stress and conflicts at home, mainly due to poor living conditions and the small size of the homes.

The perspective given by the children who participated in our contest is more positive. It must be taken into account that the survey conducted by Save The Children in Spain addressed children with poorer living conditions, which is unquestionably associated with more problems, problems that children that participated in our contest are not likely to experience during confinement.

An analysis of the available evidence on the impact of confinement in children carried out by Adrián García Ron and Isabel Cuéllar-Flores, found that while periods of confinement due to epidemics have been associated with a negative impact on mental health in adults (increased risk of mood disorders, symptoms of depression, irritability, stress…), the current evidence on children is anecdotal and the conclusions of existing studies are limited.11

As a final reflection, based on the findings of our study we concluded that drawings, stories and videos are useful tools to assess how the paediatric population perceives a risk situation. We believe that our contest contributes an additional perspective by exploring the feelings and perceptions of some children regarding this confinement, highlighting the vital importance of understanding how it was experienced by children, something to be taken into account in other environmental risk situations requiring community involvement to improve public health. This could pave the way for the development of early prevention strategies for existing or future problems.12 There is also significant interest on the part of primary care paediatricians to understand how children have experienced this confinement due to coronavirus and to promote the rigorous study of children’s drawings.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria · AITANA: Grupo de Investigación Análisis, Intervención y Terapia Aplicada (Analysis, Intervention and Applied Therapy Research Group) · BOE: Boletín Oficial del Estado · UPV: Universidad del País Vasco · WHO: World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. Available at www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/03/14/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-3692.pdf

- Concurso “En casa por coronavirus”. In: Familia y Salud [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/recursos/nuestros-concursos/concurso-en-casa-por-coronavirus

- Garrido Torrecillas FJ. Interpretar el dibujo infantil. In: Familia y Salud [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/vivimos-sanos/salud-emocional/emociones-y-familia/educando-nuestros-hijos/interpretar-el-dibujo

- Pujol Ribera E, Monteagudo Zaragoza M, Berenguer Ossó A. Investigación cualitativa en Atención Primaria de salud: situación actual, aportaciones y algunos retos. Rev Clín Electr Aten Primaria. 2011;109.

- Orden SND/370/2020, de 25 de abril, sobre las condiciones en las que deben desarrollarse los desplazamientos por parte de la población infantil durante la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. Available at https://boe.es/boe/dias/2020/04/25/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-4665.pdf

- Garrido Torrecillas FJ. Dibujar, mucho más que ser artistas. In: Familia y Salud [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/vivimos-sanos/salud-emocional/emociones-y-familia/educando-nuestros-hijos/dibujar-mucho-más-que-ser

- Ya tenemos ganadores. In: Familia y Salud [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/noticias/ya-tenemos-ganadores

- Berasategi Sancho N. (coord.) Las voces de los niños y de las niñas en situación de confinamiento por el COVID-19. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, Argitalpen Zerbitzua, Servicio Editorial; 2020.

- Espada JP, Orgilés M, Piqueras JA, Morales A. Las buenas prácticas en la atención psicológica infanto-juvenil ante el COVID. In: Clínica y Salud [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at https://tinyurl.com/y2nq56oq

- Save The children advierte de que las medidas de aislamiento social por la COVID-19 pueden provocar en los niños y niñas trastornos psicológicos permanentes como la depresión. In: Save The Children [online] [accessed 10/09/2020]. Available at www.savethechildren.es/notasprensa/save-children-advierte-de-que-las-medidas-de-aislamiento-social-por-la-covid-19-pueden

- García-Ron A, Cuellar-Flores I. Impacto psicológico del confinamiento en población infantil y como mitigar sus efectos: revisión rápida de la evidencia. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;93:57-8.

- Antezana Barrios L. Primeros trazos infantiles: una aproximación al inconsciente. Comunicación y Medios, 2003.