Vol. 21 - Num. 84

Original Papers

Paediatricians facing community health education; assessment of the usefulness of an intervention during the perinatal period

M.ª Rosa Pavo Garcíaa, M.ª Ángeles Ordóñez Alonsob, Débora Sanz Álvarezc

aPediatra. CS Villablanca. Madrid. España.

bPediatra. CS La Corredoria. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA). Oviedo. Asturias. España.

cServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid. España.

Correspondence: MR Pavo. E-mail: rosapavo.ped.garcianoblejas@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Pavo García MR, Ordóñez Alonso MA, Sanz Álvarez D. Paediatricians facing community health education; assessment of the usefulness of an intervention during the perinatal period. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2019;21:359-68.

Published in Internet: 14-11-2019 - Visits: 14498

Abstract

Introduction: the main aim of the study was to describe the current situation of Health Education (HE) programmes in primary care (PC) in Spain, and to assess the usefulness of a perinatal educational intervention in the community.

Material and methods: We conducted an observational and descriptive study in March 2019 by analysing data collected from a a survey of health care professionals. The questionnaire was distributed through a health care professional mailing list that has 1139 subscribers, most of who are primary care paediatricians.

Results: we collected 353 responses, 83.9% from female responders; 42.8% were submitted from the Community of Madrid, followed in frequency by Andalusia (12.2%) and Asturias (10.5%). Of all respondents, 84.1% reported working in sites that offered community HE, but only 38% participated in any such activities; 79.5% of midwives reported delivering HE, followed in frequency by nurses (77.8%). Of the respondents whose centres did not offer HE, 82.1% expressed a desire to participate in community HE projects, but many cited barriers to do so, including a lack of time (71.4%), a lack of co-workers willing to participate in these activities (48.2%) and inadequate training on how to lead group activities (39.3%). Also, 21.4% reported feeling unmotivated and 12.5% having negative experiences in the past.

Conclusion: the vast majority of surveyed providers considered that perinatal health education was useful, highlighting that it could empower families. Respondents considered that paediatric nurses were the health professionals best suited to deliver community health education interventions.

Keywords

● Health education ● Health promotion ● Healthy lifestyle ● Perinatal care ● Primary health careINTRODUCTION

The Primary Care (PC) health model in Spain is based on the key pillars established in the Declaration of Alma-Ata and signed at Astana1: it is comprehensive, integrated, continuous, accessible, multidisciplinary, participatory and of high quality, and constitutes a powerful tool in pursuit of equity. The PC system pays a key role in the coordination of health care resources and the continuity of care.

The strengths of primary care (universal and free coverage, accessibility and continuity of care) have brought significant improvements in quality of care and user satisfaction in the past 30 years. However, they are also at the root of the weaknesses of the system: unlimited access, the scarce economic investment in the system exacerbated by the financial crisis, inadequate planning and organization, medicalization and dependency in the health care system.2

Studies in the literature warn of the high use of health care services and the increase in the use of off-label use of multiple drugs that are not indicated for ages 0 to 6 months.3 The most recent Strategic Framework for Primary Care and Community Health Services highlights the most significant problems of the National Health System (NHS) of Spain. Chief among them are iatrogenic disease and its leading underlying causes and the overuse of health care services with the associated overdiagnosis and overtreatment. 4

Primary care paediatrics (PCP) offers health care that is accessible to children and their families, taking into account the particular characteristics of their environment and based on a holistic perspective of medicine whose main purpose is not treatment of disease but maintaining the health of the population of children and adolescents through every period of development. The paediatrician supports families in the first months of the life of a child in a social framework where the support of the extended family and the community is decreasing over time.

There is still no evidence of the potential benefits of post-birth health education delivery to parents in terms of the demand for health care services or the quality of parent-child relationships.5,6 The Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period of the NHS recommends offering postpartum support groups at the primary care level to provide psychological support after childbirth and to reinforce the acquisition of knowledge and skills previously addressed in childbirth education sessions.7

We ought to highlight the work being done by the Group on Health Education of the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics, AEPap). Recently, this group developed a programme titled Rational use of paediatric emergency services and approach to the leading health problems. If you consider it urgent… do I find it urgent too?.8

In the framework of the Strategy for Health Promotion and Prevention of the Spanish National Health System (NHS),9 a programme for positive parenting, to be delivered either online or in person, has been developed.10 There is an increased offering of HE interventions for families with children, some supported by public institutions and many others by scientific societies, paediatricians and other health care professionals. There are also similar programmes in other countries, among which we would like to highlight Start4life,11 developed by Public Health England (part of the National Health System of the United Kingdom), which also offers resources for health care professionals to carry out HE interventions at the local level.

In PCP, health prevention and promotion activities are usually delivered at the individual level in the context of the routine visits included in the schedule of the Well Child Programme (WCP), and, less frequently, in the community or in the form of prenatal activities. We have not found any recent studies in the literature performing an overall analysis of the introduction of community health education in PCP in Spain.

Following the Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978) and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986), several international organizations have emphasised the key role of community-based interventions in improving wellness and health in communities and populations. We would like to highlight the vision and definition of the Instituto de Programas Interdisciplinarios en Atención Primaria de la Salud (Institute of Interdisciplinary Programmes in Primary Health Care) of the Universidad Industrial de Santander (Colombia), which defines integral health education as a process of promoting learning to encourage citizen action and mobilization and the collective development of health care with participation of individuals and the different sectors involved in the field.

To make families ready to handle the most frequent situations and problems that may arise in childrearing, we must inform them about the normal process of delivery, postpartum and breastfeeding, newborn care, the characteristics of sleep in infancy and childhood , the prevention of diseases and the promotion of healthy habits, and train them to identify ordinary symptoms and distinguish them from alarming ones. In theory, this would lead to better child health outcomes, reduced workloads in primary care centres and hospital-based emergency departments, a growth of individual appointments in the framework of the WCP while probably improving the relationship between families and health care providers.

For the above reasons, one of the potential opportunities for improvement in PCP that paediatrics teams could get involved in would be the universal, systematic and institutionalised implementation of perinatal HE programmes.

The main objectives of this study were to describe the current situation of community-based HE at the PC level in Spain and to analyse the usefulness of community-based perinatal HE from the perspective of health professionals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted an observational descriptive study. We collected data obtained through a questionnaire developed using Google forms distributed in March 2019 thorough the primary care paediatrics mailing list (PEDIAP) of the RedIRIS network, which at the time had 1139 subscribers. We included the responses submitted over a 1-week period.

We collected data on the following aspects:

- Sociodemographic characteristics: training, autonomous community in Spain, sex, age.

- Characteristics of PC centre: setting, availability of paediatric nurses and midwives in the centre, number of caseloads, current job openings or vacancies in the centre.

- Knowledge of current regulations on HP activities in the respondent’s autonomous community.

- Current offering of group or community-based HE activities at respondent’s PC centre. If the responded reported that such activities existed, we also asked about the type of health care professional that delivered group or community-based interventions in their facility, the participation of the respondent in such activities and personal experience with HE. If respondents reported that HE activities were not offered by their centre, we asked about previous offering of such activities in the facility, willingness of the respondent to get involved in these activities, and reasons why group or community-based HE interventions were not carried out. We also asked all respondents about the existence of a system for the routine delivery of information on perinatal care to families, the perceived effectiveness of perinatal HE groups, how the respondent perceived different possible reasons why HE may be useful, and the health professional that the respondent considered was best suited for implementing group or community-based HE activities.

We stored and processed the collected data in Google and Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. We performed the statistical analysis with the software IBM SPSS Statistics. We have summarised qualitative data as absolute and relative frequencies, and quantitative data by means of measures of central tendency (mean, median) and measures of dispersion (standard deviation [SD]). We assessed the association between qualitative variables by means of hypothesis testing with the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. We compared quantitative variables in two groups by means of the Student t test, and in 3 or more groups by means of analysis of variance after verifying the homogeneity of variance and the normal distribution of data. We set the level of significance at a value of 0.05.

RESULTS

We received a total of 353 responses (83.9% from female respondents). Of all participants, 94.9% were paediatricians, 3.1% physicians that were not specialised in paediatrics and 2% other type of health care professional, such as medical interns-residents (MIR) and nurses. This amounted to 31% of subscribers to the PEDIAP mailing list, a majority of who are PC paediatricians.

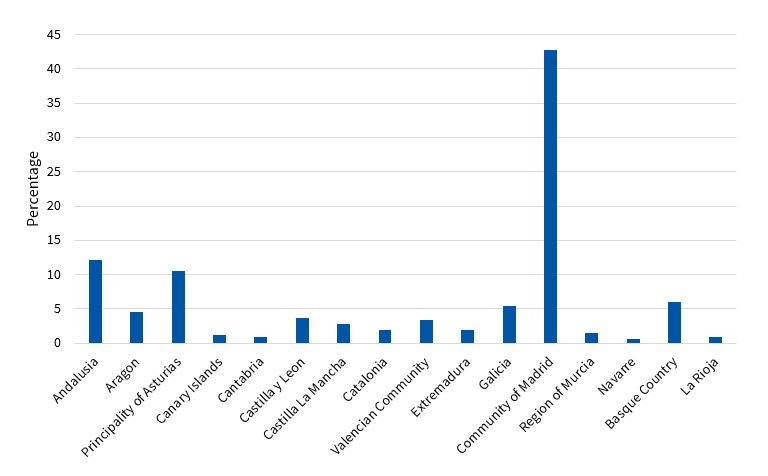

We received the greatest number of responses from the Community of Madrid (42.8%), followed by Andalusia (12.2%) and the Principality of Asturias (10.5%) (Figure 1).

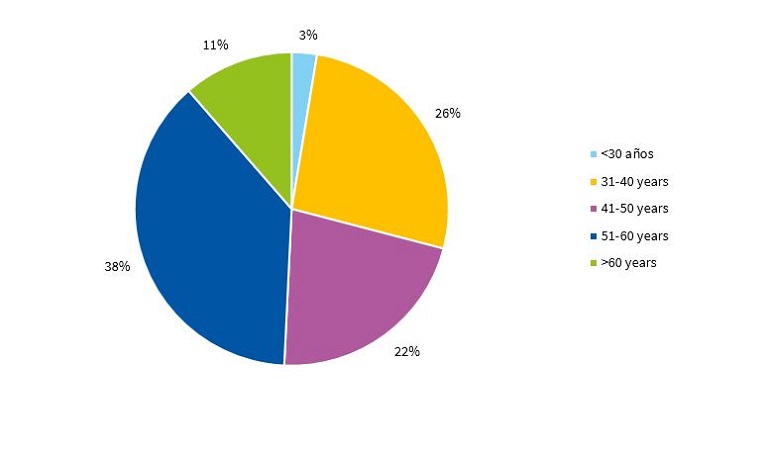

Figure 2 presents the age distribution of respondents.

Of all participants, 74.8% worked in an urban setting, 15% in a rural setting and 10.2% in a semi-urban setting.

When it came to the staff available in the paediatric team, 68.3% of respondents reported that their centres had paediatric nurses on staff and 80.2% midwives.

Respondents reported that their centre had a single paediatric caseload in 11.6% of cases; 50.4% worked in PC centres with 2 or 3 paediatric caseloads and 38% in centres with 4 or more caseloads, although 19.5% of the total reported that there were currently job vacancies in their facilities.

When it came to the regulation of the delivery of HE activities, 55% of surveyed health professionals reported not knowing about it and 20.5% that HE was not regulated in their autonomous community; 16.4% reported that HE was regulated in the framework of the official health services portfolio, while 2.3% reported that it was regulated through the service contract of the health care facility or other management contracts, and 2.9% that it was included in the framework of the WCP.

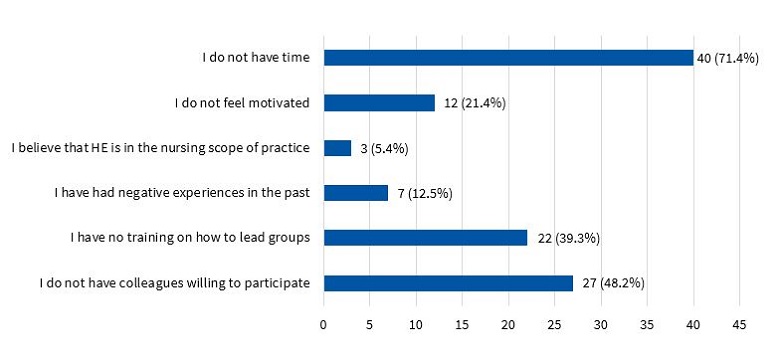

In addition, 15.9% of respondents reported that their PC centre currently did not offer any HE activities, although 35.7% of them reported their facility had previously offered HE, while 32.1% reported not knowing. Despite the lack of HE activities in their facilities, 91.1% of these respondents believed that offering workshops during the perinatal period would be useful. Furthermore, 82.1% expressed a desire to participate in HE projects, although 71.4% identified lack of time as a barrier to do so, 48.2% the absence of co-workers willing to engage in HE and 39.3% the lack of training in techniques to lead group activities. A lack of motivation was acknowledged by 21.4%, while 12.5% reported having had negative experiences in the past. Lastly, 5.4% considered that HE belonged in the nursing scope of practice (Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Barriers hindering the involvement of health professionals in community-based health education (HE) |

|---|

|

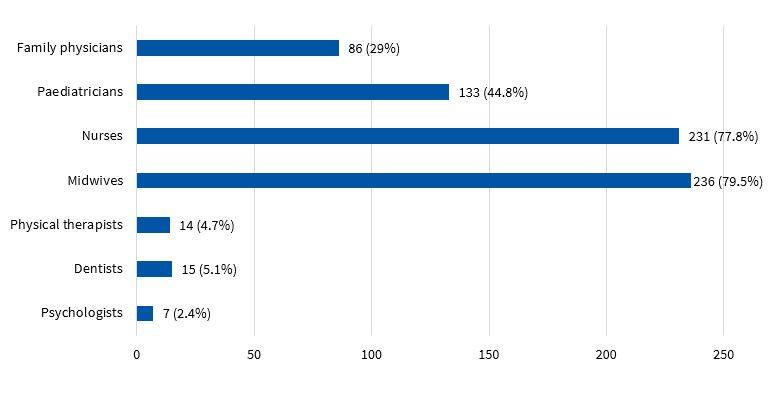

The remaining 84.1% of respondents reported that their centres currently offered some form of community-based HE. Health education was delivered by midwives in 79.5% of cases, followed in frequency by nurses (77.8%), and lastly by paediatricians, who were actively involved in 44.8% of the centres offering HE (Figure 4). Of all respondents, 38% reported being currently involved in some form of HE activity in their facility.

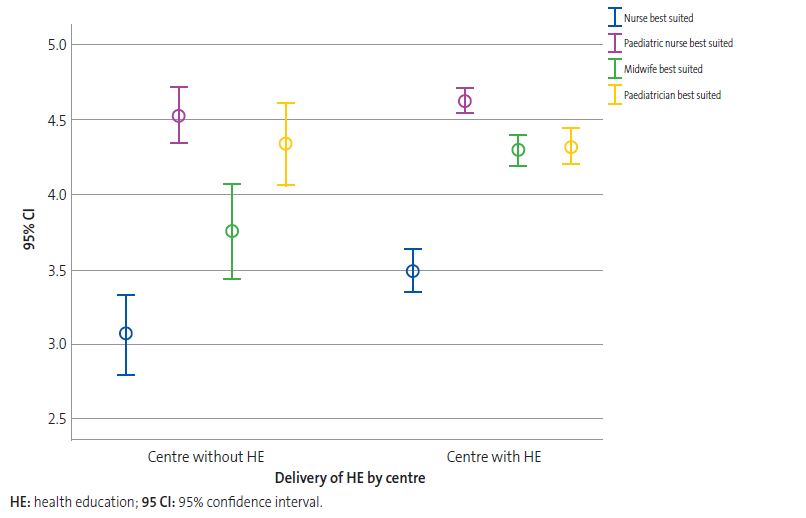

Respondents considered that paediatric nurses were the professionals best suited to deliver HE, followed by paediatricians, midwives and general nurses. We found statistically significant differences in the scores given nurses and midwives based on whether the centre where the respondent worked delivered community-based HE or not (Table 1 and Figure 5).

| Table 1. Scores (1-5) given professional roles regarding the perceived suitability to deliver health education (HE). Results expressed as mean (SD). | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents in facilities offering community-based HE | Respondents in facilities not offering community-based HE | Statistical significance (p) | |

| Paediatric nurse | 4.63 (0.71) | 4.55 (0.66) | NS |

| Paediatrician | 4.33 (0.96) | 4.36 (0.98) | NS |

| Midwife | 4.29 (0.89) | 3.75 (1.13) | <0.001 |

| General nurse | 3.49 (1.04) | 3.11 (1.04) | 0.021 |

| Figure 5. Mean score given regarding the health professional best suited to deliver health education (HE) at the primary care (PC) level in the opinion of professionals employed in centres that provide HE compared to centres that do not |

|---|

|

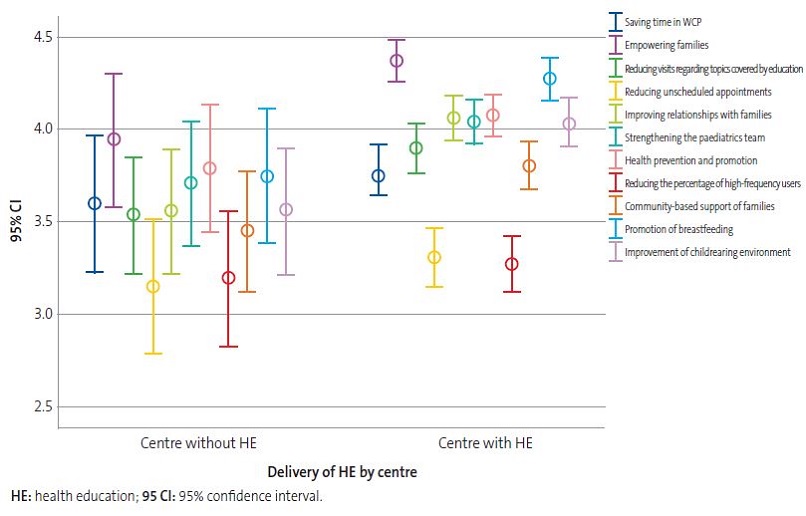

Respondents employed in facilities that did not offer community-based HE considered that the main potential benefit of perinatal HE is empowering families (mean, 4.04; SD, 1.19) followed by the prevention of accidents, diseases and health problems (mean, 3.89; SD, 1.15) (Figure 6).

| Figure 6. Perceived usefulness of delivery of community-based health education (HE) based on whether or not the centre employing the respondent offers HE |

|---|

|

Of all respondents employed in centres delivering community-based HE, 95.6% believed that delivery of perinatal HE activities would be useful. Once again, participants considered the empowerment of families the most important potential benefit (mean, 4.37; SD, 0.93) in this case followed by the promotion of breastfeeding (mean, 4.28; SD, 0.96) (Figure 6).

When it came to how participants employed in centres that offered HE versus those employed in centres that did not perceived the usefulness of HE, we only found significant differences in relation to the promotion of breastfeeding (p = 0.035).

In addition, 89.9% of respondents from centres that offered HE versus 75% of respondents from centres that did not offer HE reported that nurses or midwives in the PC centre or hospital routinely delivered education on infant care (p < 0.005).

A total of 113 health care professionals (88.5% female) reported current involvement in HE activities in their PC centres. The age group most actively involved in HE corresponded to ages 51-60 years, with a significantly greater involvement compared to all other age groups (p = 0.044). We did not find differences based on sex, number of caseloads in the facility, the number of current vacancies or the type of facility.

DISCUSSION

Paradoxically, in this age of information overload, we care for many families that lack knowledge and skills and have little experience in basic childcare, childrearing and the most common health problems in children. This translates to difficulties making decisions and dependence on health care providers.

Group HE is a type of intervention that can be integrated in the practice of PCP to provide families with knowledge, skills and tools to facilitate parenting and health promotion in children.

In our survey, respondents identified paediatric nurses and paediatricians as the professionals best suited to carry out HE activities in the community. Respondents employed in facilities that offered community-based HE gave higher scores to nurses and midwives compared to participants in facilities that did not offer community-based HE, a finding that was probably related to their actual experience in their PC centres.

It would also be interesting and enlightening to assess the participation of other professionals, such as psychologists, nutritionists, educators, etc.

The barriers cited most frequently by respondents were a lack of time in their daily practice and lack of training.

Paediatric nurses play an essential role in implementing community-based interventions and in the optimal performance of paediatric care teams. Ideally, all paediatric care teams should include a paediatric nurse, as their specialised training allows them to serve the paediatric population better. In addition, teamwork would allow distributing the workload of physicians, assigning each professional the tasks they are most efficient in performing and for which they are best trained.

Due to their experience with so-cold “childbirth classes” and their knowledge of the needs and demands of pregnant women and their partners, midwives are among the most important professionals in community-based HE programmes in Spanish PC centres. They play an essential role in developing perinatal HE programmes on account of their experience and their advantageous position to recruit families for the implementation of perinatal programmes.

Order SCO/3148/2006, which approved and detailed the academic curriculum for the speciality of paediatrics and its subspecialities specified that “The scope of Paediatrics includes everything involved in the care of healthy children and adolescents (preventive paediatrics), the approach to integrated, comprehensive and continuous care in the context of disease (clinical paediatrics) and everything that pertains to children and adolescents in their individual interpersonal relationships and their relationship with the community within the physical and human environment where they continuously develop with their individual characteristics (social paediatrics).” Of all respondents, 5.4% considered that HE was in the scope of nursing practice, and paediatric nurses were considered the health professionals best suited to deliver HE. However, as PC paediatricians we must not forget that prevention is one of our responsibilities. To achieve significant changes, we must contribute to the development and implementation of community-based programmes founded in an adequate behavioural assessment used to identify the needs of the local population and to effectively involve the community.

The newly developed and recently published Strategic Framework for Primary Care and Community Health Services4 states the need to update the primary care system to adapt it to changes in society. The framework details 100 proposals for action integrated in 6 strategic plans and 23 objectives for improving health care and reinforcing PCP and promoting its leadership in the health of the paediatric population. One of the strategic plans (D) is to “Reinforce a community-based approach, health promotion and prevention in primary care paediatrics.”

It is encouraging that the most prominent health institutions and authorities are calling for a change in the paradigm of PCP by “improving the decision-making ability of individuals, families and communities, giving rise to active or ‘activated’ users, and trying to establish a lasting partnership with the population based in shared decision making and empowering the population to become organised and use their full ability to live longer with improved wellness and a better quality of life. This requires the repurposing, restructuring and flexible use of health promotion and prevention resources and activities, possibly introducing innovative programmes to promote healthy environments and lifestyles […]”.

The most salient findings of the survey we performed to investigate the current situation of HE in our country are that nearly 16% of PC centres did not carry out any community-based activities and only 32% of respondents were currently involved in such activities. However, most participants considered that the implementation of perinatal HE programmes would be useful and identified the empowerment of families as one of the potential benefits of these interventions.

The response rate varied widely between autonomous communities. The greatest proportion of responses corresponded to Madrid, followed by Andalusia and the Principality of Asturias. We did not receive any responses from the Balearic Islands, Ceuta or Melilla.

We ought to mention the likelihood of selection bias, as we obtained the sample through a mailing list, and therefore accurate representation of the population is not guaranteed. To encourage participation, we offered an incentive upon completion of the questionnaire (https://vimeo.com/jacobfrey/thepresent).

As responsible professionals, we have the duty to get involved in the changes required to improve PCP and ensure the sustainability of the care system, analysing the extent to which we make rational use of resources, contribute to the dependency of families on paediatricians and the saturation of care services, knowingly take on tasks that other professionals could carry out more efficiently and consider what corrective actions we could implement in our care setting.

The new strategic framework brings hope to primary care practice, and community-based approaches offer an excellent opportunity for improving care or simply constitute a return to the origins of this field to recover what should have always been the role of the PC paediatrician but has been pushed to the background due to heavy caseloads with superfluous work.

CONCLUSIONS

- Most respondents considered that the implementation of perinatal HE programmes would be beneficial and expressed an interest in participating in community-based activities.

- Respondents considered that paediatric nurses were the professionals best suited for delivery of community-based HE interventions.

- The new Strategic Framework for Primary Care and Community Health Services provides an opportunity to improve PCP. As health professionals, we have the duty to contribute to the modernization of the PC system with a community-based, biopsychosocial health promotion approach.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

The study was conducted in the context of a master’s thesis, but it has not been published previously nor submitted elsewhere for publication.

María Ángeles Ordóñez and María Rosa Pavo participated in the planning and design of the study, the analysis of data, the results and the conclusions. Débora Sanz contributed to the statistical analysis of the data. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

ABBREVIATIONS

AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria · HE: health education · MIR: medical intern resident · NHS: National Health System · PC: primary care · PCP: primary care paediatrics · SD: standard deviation · WCP: Well Child Programme.

REFERENCES

- Declaration of Astana. In: World Health Organization [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf

- Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Valdivia Jiménez C. La Pediatría de Atención Primaria en el sistema público de salud del siglo XXI. Informe SESPAS 2012. Gac Sanit. 2012;26:82-7.

- Ordóñez Alonso MÁ, Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Pérez Candás JI, López Vilar P, Fernández Francés M, Coto Fuente M, et al. Influencia de la asistencia a guarderías en la frecuentación en Urgencias y Atención Primaria. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2016;18:243-52.

- Resolución de 26 de abril de 2019, de la Secretaría General de Sanidad y Consumo, por la que publica el Marco estratégico para la Atención Primaria y comunitaria. In: Boletín Oficial del Estado [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2019-6761

- Bryanton J, Beck CT, Montelpare W. Postnatal parental education for optimizing infant general health and parent-infant relationships. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD004068.

- Gagnon AJ, Sandall J. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD002869.

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de práctica clínica de atención en el embarazo y puerperio. Guía de práctica clínica de atención en el embarazo y puerperio. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/GPC_de_embarazo_y_puerperio.pdf

- Vázquez Fernández ME, Núñez Jiménez C, Serrano Poveda M. Programa de EPS. Uso racional de los servicios de urgencias pediátricas y actuación ante los principales problemas de salud. Si es urgente para ti… ¿Es urgente para mí? In: AEPap [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.aepap.org/sites/default/files/documento/archivos-adjuntos/educacion_para_la_salud_web_pdf_urgencias.pdf

- Estrategia aprobada por el Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud el 18 de diciembre de 2013. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/Estrategia/docs/EstrategiaPromocionSaludyPrevencionSNS.pdf

- Rodrigo MJ, Martín JC, Máiquez ML (dirs.). Parentalidad positiva: ganar salud y bienestar de 0-3 años. Guía para el desarrollo de talleres presenciales grupales. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/Estrategia/docs/Parentalidad_Positiva.pdf

- Start4Life [online] [accessed 05/11/2019]. Available at www.nhs.uk/start4life