Vol. 19 - Num. 73

Original Papers

Co-sleeping in our environment: case-control study in Paediatric Primary Care offices

Raquel Martín Martína, Marciano Sánchez Bayleb, M.ª Carmen Teruel de Franciscoc

aPediatra. CS Párroco Julio Morate. Madrid. España.

bPediatra. Fundación para la Investigación, Estudio y Desarrollo de la Salud Pública. Madrid. España.

cPediatra. CS Cea Bermúdez. Madrid. España.

Correspondence: R Martín. E-mail: raquelmartin333@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Martín Martín R, Sánchez Bayle M, Teruel de Francisco MC. Co-sleeping in our environment: case-control study in Paediatric Primary Care offices. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2017;19:15-21.

Published in Internet: 07-02-2017 - Visits: 21320

Abstract

Objective: to study the prevalence of co-sleeping in in the families of children attending pediatric Primary Care consultations and its relation with a certain number of aspects of their upbringing.

Patients and methods: case-control study with assessment questionnaires. A total of 317 surveys were collected from parents of children between the ages of 6 and 24 months who belonged to two Primary Care consultations in Madrid-Spain. Children who practiced co-sleeping were considered as cases whereas those who did not were considered control group. The number of nocturnal awakenings, episodes of lower respiratory tract infection and the duration of exclusive or complementary breastfeeding have been used as outcome indicators.

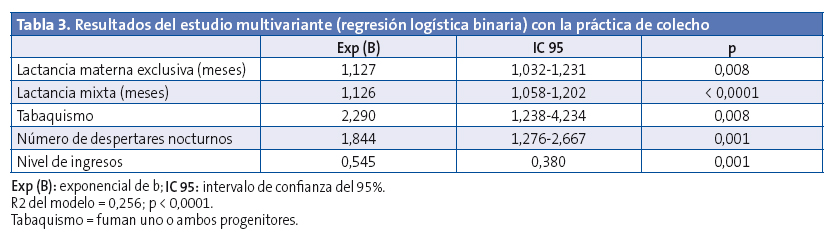

Results: the variables positively related to co-sleeping in the multivariate analysis are: the duration of exclusive breastfeeding, odds ratio (OR) = 1,127 (p = 0,008) and complementary breastfeeding, OR = 0,126 (p < 0,0001); the number of nocturnal awakenings over three times, OR = 1,844 (p = 0,001) and smoking habit by one or both progenitors OR = 2,290 (p = 0,008). The socioeconomic level acts as a protection factor OR = 0,545 (p = 0,001). The presence of lower respiratory tract infections was more frequent in the co-sleeping group, but had no statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusions: the results indicate that co-sleeping favours breastfeeding and its extension through time. Nevertheless, it also favours children’s nocturnal awakening and increases the risk of lower respiratory infections. The low socioeconomic level of the families and tobacco smoking are factors that favour co-sleeping.

Keywords

● Co-sleepingINTRODUCTION

Sleep habits in children, including the practice of parents and children sleeping together, is closely associated with parenting styles, as is the case with breastfeeding.1

Co-sleeping is understood as the child sleeping habitually—that is, every night and for at least four hours—in the same surface as the adult caregiver. These caregivers are usually parents, but may also be other members of the family; the sleeping surface is usually the bed, but it can be an armchair or sofa, as there are many different sleeping arrangements.2

Co-sleeping (also known as bed-sharing) is an English neologism. In the XIX century, it was very common for European peasants to share a single bed for the entire family, and the separation of parents and children during sleep was associated with economic progress and a cultural shift in the perception of the relationship of the individual with prioritizing the development of individuality and autonomy in the child.3

On the other hand, co-sleeping continues to be a widespread practice in Eastern societies, where children are considered to be independent at birth and requiring integration in the family, so that co-sleeping is a means of socialisation.4

From an anthropological perspective, the separate sleeping of human infants is an evolutionary exception, as primates and mammals sleep in physical contact with their mothers after birth.5

At present, co-sleeping is being reintroduced in Western societies due to the influence of advocates of attachment parenting. This term was coined by William Sears, a paediatrician from the United States, and is an approach based on the principles of John Bowlby’s attachment theory according to which the secure attachment that forms through a warm, intimate, protective and continuous relationship between child and caregiver sets the foundations for the harmonious physical and psychological development of human beings.6

On the other hand, Western perspectives take into account the arguments of biomedical research, so there are detractors of co-sleeping, and paediatrics scientific societies generally do not recommend it unless it is practised under conditions that guarantee the maximum possible safety in the mother-child environment.7-9

The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence of co-sleeping in the families served by the paediatrics clinics in two urban health care centres in Madrid, and assess its association with breastfeeding, the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections and the frequency of nighttime wakings in the children under study.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a case-control study using data obtained through a survey. The survey was based on the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire (BISQ), a short sleep questionnaire for children aged 5 to 24 months, that we adapted with the addition of other variables in the final questionnaire (reliability: Cronbach α, 0.731 [P < .0001]; validity: confirmatory factorial analysis and item-test correlation coefficient).

The survey included 317 children aged 6 to 24 months that visited two paediatric clinics in two urban health care centres in Madrid (Spain). The total caseload assigned to these two clinics was of 2745 children, 563 of which were in the 0-to-2 years age band. A randomly selected sample of the families that made scheduled or on-demand visits between April and December of 2015 was invited to participate in the survey, and the final sample consisted of all that accepted. None refused to complete the questionnaire. We considered families that practised co-sleeping cases and families that did not controls, and defined co-sleeping as the child sleeping habitually with a caregiver on the same surface.

We collected data for the following variables: age and sex of children, age and country of origin of the father and mother, situation of the family taking into account whether the parents lived together or apart, educational attainment, household income level, parental smoking, duration of exclusive or mixed breastfeeding, age of child when co-sleeping was initiated and duration of co-sleeping, reason for co-sleeping, agreement of parents regarding co-sleeping, incidence of lower respiratory tract infections and number of nighttime wakings.

We classified the sample into three groups based on income level: households with monthly incomes 1) of less than 1000 euro; 2) between 1000 and 2000 euro, and 3) more than 2000 euro. Likewise, we created three groups based on educational attainment: 1) no education or elementary education; 2) secondary education, and 3) higher education.

The outcome measures used in this study were the duration in months of both exclusive and mixed breastfeeding, the proportion of children that had more than 3 wakings per night, and the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections.

We performed the statistical analysis with the software SPSS® 15.0. We expressed basic quantitative data as mean and standard deviation (SD) and qualitative data as frequencies and percentages. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We compared quantitative variables with the Mann-Whitney U test after finding that they were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Qualitative variables were compared with the Χ2 test. We defined statistical significance as a p-value of less than 0.05.

We performed a binary logistic regression multivariate analysis with backward elimination of variables until only those that were statistically significant were left in the model.

RESULTS

Between April and December of 2015, we collected data for 317 children, of who 154 (48.58%) were male and the rest female, with a mean age of 13.67 months (SD, 6.03; range, 6 to 24 months). Co-sleeping was practised in 101 children, who constituted the cases, and the remaining 216 that did not co-sleep formed the control group. The mean maternal age was 33.46 years (SD, 4.76) and the mean paternal age was 36.21 years (SD, 56).

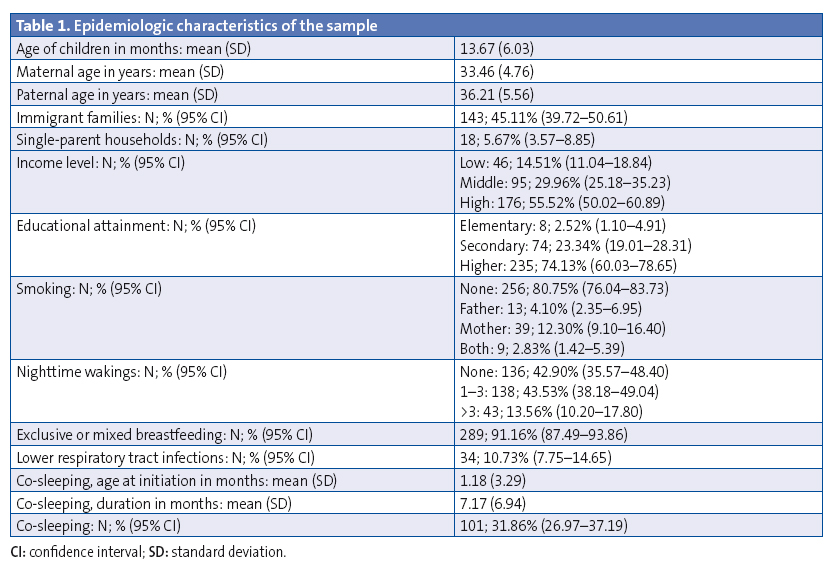

In 143 families (45.11%) at least one parent was an immigrant, and 18 were single-parent households (5.67%), headed by the mother in all instances. When it came to income, we found 46 families (14.51%) in the low-income group, 95 (29.96%) in the middle-income group, and 176 (55.52%) in the high-income group. As for educational attainment, 8 respondents (2.52%) had completed elementary education or had no education, 74 (23.34%) had a secondary education and 235 (74.13%) a higher education (Table 1).

Co-sleeping was practised by 41.91% of the immigrant subset, 50% of single-parent households and 50% of the low-income group, and it was significantly more prevalent (P < .0001) in families with a lower socioeconomic level (41.30%) compared to those with a higher socioeconomic level (21.59%).

In our survey, 49.5% of parents reported they practised co-sleeping because they believed it beneficial, and in 97.50% of cases both partners were in agreement about this practice.

On average, co-sleeping was initiated at age 1.18 months, with a range of 0 to 23 months (SD, 6.94).

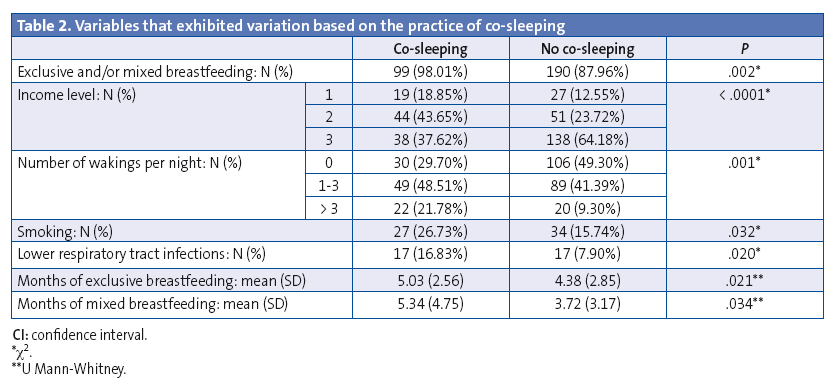

In the co-sleeping group, 98.01% of children were breastfed with a mean duration of exclusive breastfeeding of 5.03 months (SD, 2.56) and a mean 5.34 months of mixed breastfeeding (SD, 4.75), and 21.78% had more than 3 wakings per night. These results were statistically significant when compared to the control group (Table 2). Respiratory infections occurred in 16.83% of the children that co-slept, compared to 7.90% of children in the control group, a difference that was statistically significant (P = .020). In the multivariate analysis, the variables that continued to have a significant positive association with co-sleeping were exclusive and mixed breastfeeding, the number of nighttime wakings and smoking in one or both parents, while socioeconomic level emerged as a protective factor (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Families usually approach childrearing with the knowledge acquired through personal experience, which in turn was moulded by the social and cultural values of the area where the lives of its members unfolded.10,11

How and where parents and children sleep shapes the parenting style and constitutes a very intimate aspect of family life. Furthermore, consultations about sleep ecology in children are frequent in primary care paediatrics clinics, and co-sleeping is a highly controversial subject in terms of its risks and benefits, a subject on which Horsley et al published an interesting systematic review.12

Despite the interest aroused by this subject, there are few studies on the prevalence of co-sleeping in Spain. In a study conducted in postpartum mothers, Roldán13 reported that 12% intended to co-sleep with their infants. López Pacios14 found a prevalence of co-sleeping of 8.6%, compared to the 31.86% found in our study, although his study was conducted in a considerably different geographic and social context. In our sample, 49.5% of parents chose to co-sleep because they believed it was beneficial for the family, with both partners agreeing on it in 97.50% of two-parent households that practiced co-sleeping.

Economic factors shape societies, and the habits developed by their members are influenced by their socioeconomic status;14 thus, we found a prevalence of co-sleeping of 50% in single-parent households and of 41.95% in immigrant families, a population that was amply represented in our sample, demonstrating that low socioeconomic status and smaller living quarters increase the likelihood of children sleeping in the same surface as parents.

Critics of co-sleeping consider that it poses a safety hazard and can be life-threatening to infants, with a significant association with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). There were no cases of SIDS in the period and population under study, but we could not assess this outcome due to our sample size, as the incidence of SIDS in Spain ranges between 0.15 and 0.23 deaths per 1000 live births.16-21 Clinical practice guidelines on paediatric sleep disorders underscore the importance of co-sleeping under safe conditions, and parental smoking has been identified as a risk factor. In 44.26% of our sample, at least one of the parents was a smoker, and more mothers smoked than did fathers; the medical literature also shows that the prevalence of smoking continues to be very high in women of childbearing age in Spain.22

We did not find any studies in the literature to compare our statistically significant finding of a higher incidence of lower respiratory tract infections in children that co-sleep with their parents compared to children with separate sleeping arrangements.

This physical proximity is advantageous when it comes to breastfeeding, as it is facilitated and maintained for longer periods in children that co-sleep, a point on which the literature is consistent.23-25 There is also an interesting study conducted in the Philippines26 that found that fathers that sleep close to their offspring have lower levels of testosterone, which may facilitate bonding.

The frequency of nighttime wakings in children that co-slept with parents was significantly higher than in children that slept alone, a finding was consistent with those of other studies.27-29 Many of the children under study, aged 6 to 24 months, continued breastfeeding, so the maintenance of breastfeeding could be associated with the increased frequency of nighttime wakings, which would not necessarily constitute a sleep disorder.

Thus, we can conclude that our results show that co-sleeping promotes breastfeeding, but on the other hand is associated with an increased likelihood of waking more than three times per night and an increased incidence of lower respiratory tract infections in children.

There are limitations to our study, chief of which is the small sample size, so it would be advisable to continue investigating this subject with larger samples. Furthermore, we think that it is important for health care providers to have a thorough knowledge of this subject30-32 to be able to educate families without the interference of personal bias, as it would not be professional to allow ourselves to be influenced by theories that fit our own beliefs; parents are ultimately responsible for making the decision, assisted by the information provided by the paediatrician.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation with the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS: CI: confidence interval · SD: standard deviation · SIDS: sudden infant death syndrome.

REFERENCES

- Fleming PJ, Blair PS. Making informed choices on co-sleeping with your baby. BMJ. 2015;350:h563.

- Aparicio Rodrigo M, Ochoa Sangrador C, García Vera C. Colecho, ventajas e inconvenientes. En: AEPap ed. Curso de Actualización Pediatría 2011. Madrid: Exlibris Ediciones; 2011. p. 75-82.

- Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Kohyama J, How TH. Parental behaviors and sleep outcomes in infants and toddlers: a cross-cultural comparison. Sleep Med. 2010;11:393-9.

- Shimizu M, Park H, Greenfield PM. Infant sleeping arrangements and cultural values among contemporary Japanese mothers. Front Psychol. 2014;5:718.

- Landa Rivera L, Díaz-Gómez M, Gómez Papi A, Paricio Talayero JM, Pallás Alonso C, Hernández Aguilar MT, et al. El colecho favorece la práctica de la lactancia materna y no aumenta el riesgo de muerte súbita del lactante. Dormir con los padres. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2012;14:53-60.

- Bowlby J. El vínculo afectivo. Barcelona: Paidós; 1998.

- González C. Bésame mucho. Barcelona: Temas de hoy; 2012.

- Estivill Sancho E. Insomnio infantil por hábitos incorrectos. Rev Neurol. 2003;30:188-191.

- Estivill Sancho E. Duérmete niño: 12 años de experiencia. Revisión crítica. An Esp Pediatr. 2002;56:35-9.

- Xianchen L, Lianqi L, Ruzhan W. Bed sharing, sleep habits and sleep problems among Chinese school-aged children. Sleep. 2003;26:839-44.

- Esposito G, Setoh P, Bornstein MH. Beyond practices and values: toward a physio-bioecological analysis of sleeping arrangements in early infancy. Front Psychol. 2015;6:264.

- Horsley T, Clifford T, Barrowman N, Bennett S, Yazdi F, Sampson M, et al. Benefits and harms associated with the practice of bed sharing: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:237-45.

- Roldán Chicano MT, GarcíaLópez MM, Blanco Soto MV, Vera Pérez JA, García Ros JM, Cebrián López R. Intención de colecho en el puerperio según características sociodemográficas de las madres. ¿Qué podemos recomendar los profesionales de enfermería? Index Enferm. 2009;18:8-12.

- López Pacios D, Palomo de los Reyes MJ, Blanco Franco MP, Fidalgo Alvarez I, Rodriguez Iglesias R, Jiménez Rodríguez M. Hábitos del sueño en un grupo de niños de 6 a 24 meses. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2005;7:579-86.

- Martín Martín R, Sánchez Bayle M, Gancedo García C, Teruel de Francisco MC, Coullaut López A. Las familias de la crisis en las consultas pediátricas de Atención Primaria: estudio descriptivo observacional. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;84:189-94.

- Libro Blanco de la Muerte Súbita. Evolución del Síndrome de la muerte súbita del lactante en los países desarrollados. Situación actual en España. Madrid: AEP; 2003. p. 9.

- Hauck FR, Herman SM, Donovan M, Iyasu S, Merrick Moore C, Donoghue E, et al. Sleep environment and risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1207-14.

- Blair PS, Fleming PJ, Smith IJ, Ward Platt M, Young J, Nadin P, et al. Babies sleeping with parents: case-control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1999;319:1457-62.

- Ruys JH, de Jonge GA, Brand R, Engelberts AC, Semmekrot BA. Bed-sharing in the first four months of life: a risk factor for sudden infant death. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1399-403.

- Carpenter R, McGarvey C, Mitchell EA,Tappin DM, Vennemann MM, Smuk M, etal. Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case-control studies. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002299.

- Scragg R, Mitchell EA, Taylor BJ, Stewart AW, Ford RPK, Thompson JMD, el al. Bed sharing, smoking and alcohol in the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ. 1993;307:1312-8.

- Jiménez-Muro A, Samper MP, Marqueta A, Rodriguez G, Nerín I. Prevalencia de tabaquismo y exposición al humo ambiental de tabaco en las mujeres embarazadas: diferencias entre españolas e inmigrantes. Gac Sanit. 2012;26:138-44.

- Esparza Olcina MJ, Aizpurua Galdeano P. Amamantar al bebé y compartir la cama con él a los tres meses de vida se relaciona con una mayor prevalencia de lactancia materna al año. Evid Pediatr. 2010;6:11.

- Blair PS, Heron J, Fleming PJ. Relationship between bed sharing and breastfeeding: longitudinal population-based analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1119-e1126.

- Tan KL. Bed sharing among mother-infant pairs in Klang district, Peninsular Malaysia and its relationship to breast-feeding. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:420-5.

- Gettler LT, McKenna JJ, McDade TW, Agustin SS, Kuzawa CW. Does cosleeping contribute to lower testosterone levels in fathers? Evidence from the Philippines. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e 41559.

- Hysing M, Harvey AG, Torgensen L, Ystrom E, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Sivertsen B. Trajectries and predictors of nocturnal awakenings and sleep duration in infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35:309-16.

- Mao A, Burnham MM, Goodlin-Jones B, Gaylor EE, Anders TF. Acomparison of the sleep-wake patterns of cosleeping and solitary-sleeping infants. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev. 2004;35:95-105.

- Gaylor EE, Burnham MM, Goodlin-Jones BL, Anders TF. A longitudinal follow-up study of young children`s sleep patterns using a developmental classification system. Behav Sleep Med. 2005;3:44-61.

- González Rodríguez C. El sueño en el primer año de vida: ¿cómo lo enfocamos? Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria Supl. 2011;20:95-9.

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastornos del Sueño en la Infancia y Adolescencia en Atención Primaria. Guía de práctica clínica sobre trastornos del sueño en la infancia y adolescencia en Atención Primaria. Plan de calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad. Unidad de Evaluación de Tecnologias Sanitarias de la Agencia Laín Entralgo; 2011. Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS: UETS N.º 2009/8.

- Bruni O, Baumgartner E, Sette S, Ancona M, Caso G, Di Cosimo ME, et al. Longitudinal study of sleep behavior in normal infants during the first year of life. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:1119-27.