Vol. 14 - Num. 56

Original Papers

Influence of day care attendance on morbidity in children under 12 months of age

Begoña Domínguez Aurrecoecheaa, Mercedes Fernández Francésb, M.ª Ángeles Ordóñez Alonsoc, P López Vilard, L Merino Ramose, A Aladro Antuñaf, E Díez Estradag, Francisco J Fernández Lópezh, José Ignacio Pérez Candási, AM Pérez Lópezi

aPediatra. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA). Asturias. España.

bCS La Corredoria. Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA). Asturias. España.

cPediatra. CS La Corredoria. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA). Oviedo. Asturias. España.

dPediatra. CS Puerta de la Villa. Gijón. Asturias. España.

ePediatra. CS de Luanco. Asturias. España.

fPediatra. CS de Otero. Oviedo. Asturias. España.

gPediatra. CS de Pumarín. Oviedo. Asturias. España.

hPediatra. CS de Nava. Nava. Asturias. España.

iPediatra. CS de Sabugo. Avilés. Asturias. España.

Correspondence: B Domínguez. E-mail: begoa.dominguez@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Fernández Francés M, Ordóñez Alonso MA, López Vilar P, Merino Ramos L, Aladro Antuña A, et al. Influence of day care attendance on morbidity in children under 12 months of age. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2012;14:303-12.

Published in Internet: 14-12-2012 - Visits: 37510

Abstract

Introduction: the current structure of Spanish society favors the attendance of children at day care to increasingly early ages. This is a risk factor in itself to the condition of infection of the upper and lower respiratory tract, as well as acute otitis media, gastrointestinal infections and other infections.

Objective: to evaluate the influence of day care attendance on the risk of infections in children under 12 months of age.

Population and methods: prospective longitudinal study. Children born between 1 January and 30 September 2010, attending primary care pediatrics’ offices, were included. We excluded children who had severe respiratory or cardiac disease or severe immune deficiency. The data were obtained from computerized medical records and interviews with parents in scheduled visits at 6 and 12 months. In the statistical analysis of the data the statistical software R© (R Development Core Team, 2011) was used.

Results: children who attend day care have one or more infectious episodes in higher percentages with statistically significant (p-value <0.05) differences for bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, tonsillopharyngitis, acute gastroenteritis, laryngitis, pneumonia, acute otitis media, common cold, wheezing, sinusitis and for total pathologies. Attendance at nursery could be responsible for between 35% and 50% of the acute otitis, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis and bronchitis.

Conclusion: taking into account these results, it seems advisable to try other different ways for the care of children in early ages.

Keywords

● Infectious diseases ● Nursery ● Prospective study ● RiskINTRODUCTION

The current structure of Spanish society, with the incorporation of women into the workforce, the increase in the number of single-parent homes, and the economic burden involved in hiring a childminder, encourages the enrolment of children in childcare centres at increasingly early ages. According to the latest population surveys in our country, 20.7% of the employed population reports using specialised services for the care of their children, with a wide variation between autonomous communities, from 13% in Extremadura to 28.9% in Madrid1.

The maternity leave period in Spain lasts 16 weeks, while in the rest of the European Union (EU) it is 20 weeks long, and 96 weeks long in Sweden. The breastfeeding breaks in Spain consist of one hour a day until the ninth month. Thus, the childcare centre becomes a social demand and need, and does have an influence on the child’s health2.

Families often consult with the paediatrician and seek advice regarding the best care for their children: the use of a specialised centre (childcare centre) as opposed to other options in those cases where they may be available (a grandparent, another family member, or a hired caregiver).

Attendance at childcare centres is in itself a risk factor for suffering upper3 and lower respiratory tract infections, as well as acute otitis media4, gastrointestinal infections, and other infections.

Most of the published studies have been done in countries with education and employment systems (maternity leaves and breastfeeding breaks) that differ from our own. The few studies carried out in Spain also show a higher risk of infection5,6, although the proportions are different. The literature review published in 2007 compiles the information of 52 studies, of which only one was done in Spain7. Among the factors that have an influence, the most important one is the age at which the child starts attending the childcare centre8.

Thus, we face a reality that has a marked influence on the everyday health of children, on the healthcare burden, on the emergence of antibiotic resistance, and therefore on the decisions that the paediatrician has to make on a daily basis. Since the studies in our environment are scarce, it seems pertinent that we do a prospective multi-centre study analysing several dependent variables.

Our stated objective is to assess the influence of childcare centre attendance on the risk of infection in children younger than 12 months.

POPULATION AND METHODS

Type of study

Prospective longitudinal study of two cohorts of children aged 0-12 months, differentiated solely by their attending or not attending childcare (exposure factor).

Population under study

The study included children born between January 1st and September 30th 2010 served by the Paediatric Primary Care (PC) clinic and whose families agreed to their participation after being informed in full about the study.

It excluded children who presented a severe respiratory pathology, a severe heart pathology requiring surgical treatment, or severe immunodeficiencies, and children who did not come routinely to paediatric visits.

The study involved the participation of 35 paediatricians and 20 nurses from the eight healthcare districts of the Principality of Asturias.

Sample size: we calculated a sample size of 1025 cases taking into account the incidence of pneumonia (4%) as the most important of the common infections that were the subject of our study.

Variables in the study

Independent variable: childcare centre attendance (dichotomous qualitative variable), which defines both cohorts.

As dependent variables, we analysed the number and type of infections contracted (bacteraemia, bronchiolitis, acute bronchitis, conjunctivitis, exanthematous viral diseases, pharyngitis, pharyngoamygdalitis, acute gastroenteritis, influenza, laryngitis, meningitis, pneumonia, acute otitis media, common cold, sepsis, wheezing, sinusitis, others) that were pre-defined according to the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics2. We also analysed personal and family characteristic variables.

Data collection

The data were collected from the computerised clinical histories and in interviews performed during scheduled routine check-ups at 6 and 12 months of age. The data pertaining to the characteristic variables were gathered in the first visit, and those regarding the response variables were collected at 6 and 12 months and recorded in forms that had been designed for that purpose.

The informed consent given to parents included an explicit statement of compliance and adherence to laws and ethical guidelines.

During the first visit, at six months of age, we gathered the data pertaining to:

- Personal characteristics: code, date of birth, sex, gestational age, birth weight, and presence or absence of neonatal pathology, BF, routine immunisations scheduled in the Autonomous Community of the Principality of Asturias, and optional immunisations (pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines), weight, height, and growth percentiles.

- Family characteristics: siblings, and, in regard to the father and the mother, the age, level of education, whether employed or not, tobacco use, allergies, and asthma.

- Attending or not attending a childcare centre; age at initial enrolment and reason for attending or not attending.

- Number and type of infections (according to pre-set definitions).

During the 12-month visit, we collected:

- Vaccine schedule (routine and optional), BF.

- Attendance at a childcare centre, or not.

- Infectious pathology suffered, and number of episodes.

Statistical analysis

To do the statistical analysis of the data, we used the statistical software R® (R Development Core Team, 2011), version 2.14. To analyse the relationship between childcare centre attendance and the factors under study, we used Pearson’s chi-square test.

To analyse the quantitative variables we used Student’s t-test or Welch’s test, after ensuring the normality of the distribution using the Shapiro-Wilks test, and the equality of scale by the Ansari-Bradley test. In the case of qualitative variables, we used Pearson’s chi-square test. We are also presenting the relative risks and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals to quantify the risk of suffering the pathologies with the highest incidence rates in association with whether the child does or does not attend a childcare facility.

RESULTS

We gathered data for 1139 children at six months of age and for 1092 children at 12 months, which entailed a 4.1% attrition rate that was mostly due to changes in residence.

Description of the population under study

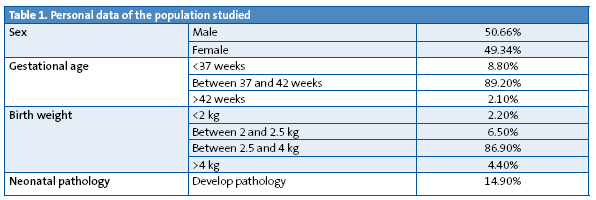

- Personal data. Table 1 shows the characteristics of sex, gestational age, birth weight, and presence or absence of neonatal pathology for the children included in the study.

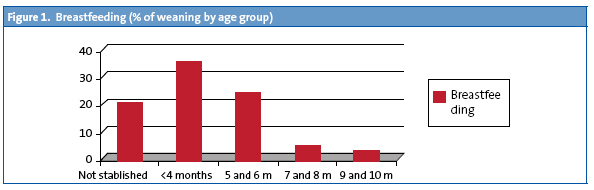

- BF. 80% of the children were BF as newborns; the highest percentage of weanings occurred before six months of age (Fig. 1) and at 11 months, 8.9% of the children continued to breastfeed.

- Vaccine schedule. At 12 months of age, 100% of the population under study had been immunised in compliance with the official schedule of the Principality of Asturias. 19.4% of the children were vaccinated against rotavirus; 82.6% had been vaccinated against pneumococcus.

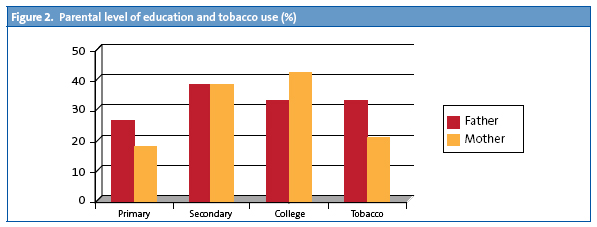

- Family and social characteristics. 59.7% did not have siblings, 33.8% had one sibling, 5.2% had two, and 1.3% had more than two. The fathers’ ages were distributed as follows: 43% were between 21 to 34 years old; 39.4%, between 35 and 40 years old, and 16.8% were older than 40; 93.5% were employed. As for the mothers, 59.7% were between 21 and 34 years old; 33.7% between 35 and 40 years old, and 5.2% were older than 40; 70.6% were employed. The data on the educational level of both parents and their tobacco use are presented in percentages in Fig. 2.

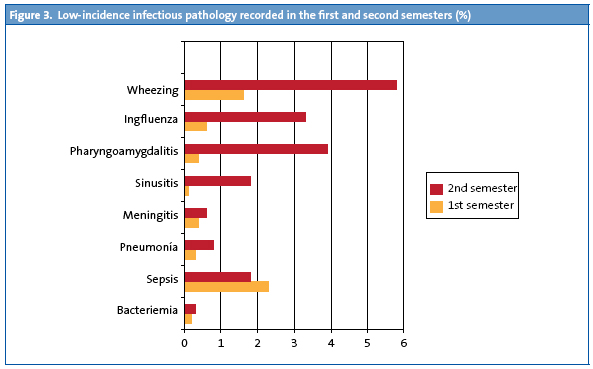

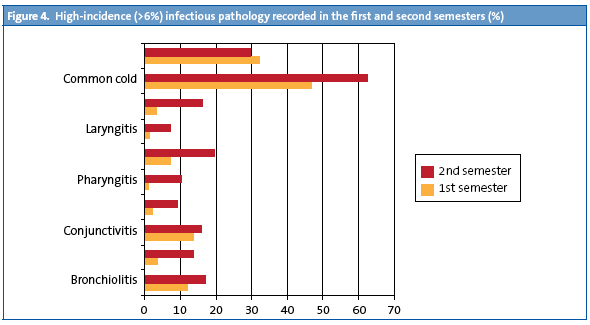

- Infectious pathology. The study describes (in percentages) the evolution of pathology recorded at 6 and 12 months of age in the entire study sample. Fig. 3 shows pathologies with incidence rates below 6%, and Fig. 4 the pathologies with higher incidence rates. We observed that in the second semester of life the rate had increased for all infectious pathologies except for sepsis cases, which were more frequent in the first trimester on account of neonatal sepsis. The section devoted to other pathologies is larger in the first six months of life, and corresponds to non-infectious pathologies.

Childcare centre attendance

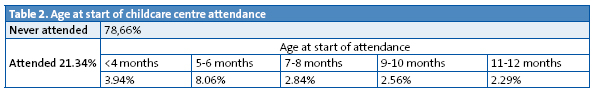

By 12 months of age 21.34% of the children attended childcare (Table 2). The age at initial enrolment was before age four months in 3.94% of the children, and it peaked between five and six months of age, coinciding with the end of the maternity leave period; after that, enrolment increased gradually until 12 months.

Factors that influence attending a childcare centre

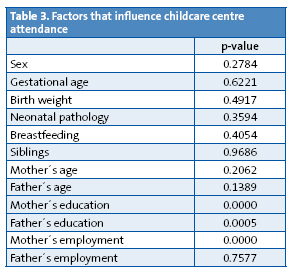

- Among the factors we studied, the employment status of the mother and the educational level of both parents had a significant influence (p=0.05) on childcare centre attendance (Table 3).

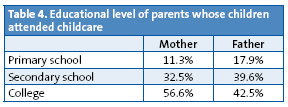

- The mother was employed in 89.4% of the cases in which children attended childcare, and children attended in higher proportions when the parents had attended college (Table 4).

Behaviour of the two cohorts (children who did or did not attend childcare) in relation to specific infectious pathologies and to any of the pathologies

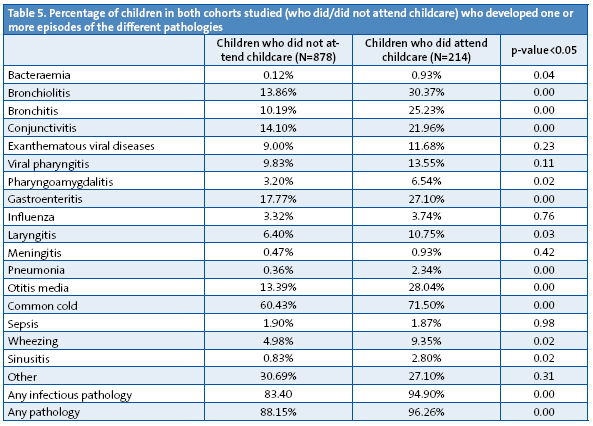

The children who attended childcare centres developed one or more episodes in higher percentages than those children who did not attend childcare, and we found statistically significant differences (p<0.05) in the incidence of bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, pharyngoamygdalitis, acute gastroenteritis, laryngitis, pneumonia, acute otitis media, the common cold, wheezing, sinusitis, and pathologies in general (Table 5).

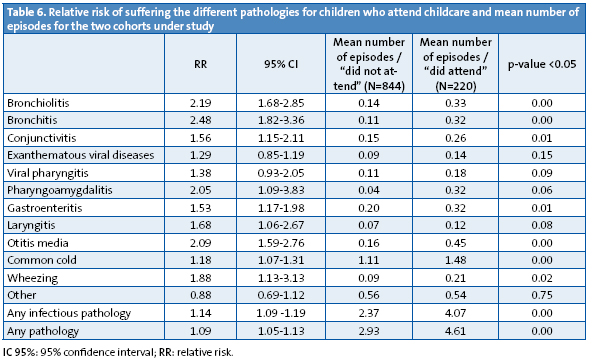

The relative risk (RR) of developing pathologies with an incidence rate above 4% in children who attend childcare is presented in Table 6.

The differences are significant for: bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, pharyngoamygdalitis, acute gastroenteritis, laryngitis, acute otitis media, the common cold, wheezing, and for pathologies in general.

Compared to children who do not attend a childcare centre, children who do attend have twice the RR or more of developing bronchiolitis, bronchitis, pharyngoamygdalitis and acute otitis media.

The cohorts do not behave the same if we study the average number of episodes suffered (Table 6). Compared to children who did not attend a childcare centre, those who did developed more episodes on average (a difference that was statistically significant, p<0.05) for the following pathologies: bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, gastroenteritis, acute otitis media, common cold, and wheezing.

DISCUSSION

We are carrying out a prospective multicentre study within the framework of primary care paediatric visits that involves the participation of a large number of paediatricians and nurses, which allowed us to obtain a large sample. We have collected data during routine visits, trying to maximise the research potential of the primary care paediatric offices.

The participation of a large number of professionals also brings some weaknesses to the project, the most important of which is the potential heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria, which we tried to minimise by setting definitions for these criteria prior to the start of the study.

The sinusitis diagnosis may be controversial; since the computer coding system based on the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) used in the clinics does not have a diagnostic code for episodes of superinfection in upper respiratory tract pathologies, we decided to include these processes in the sinusitis diagnosis.

We also included wheezing episodes since they can involve a severe pathology, and there is a high prevalence of these episodes in Asturias (45.6% of children suffer from a wheezing episode within the first 36 months of life)9. Although this is not an infectious pathology, knowing how its incidence is affected by attending or not attending childcare is of great interest.

While it was not one of the objectives of this study, given the low number of studies that provide morbidity data for these age intervals, we decided to include the data about the incidence of pathologies recorded in the first and second semesters of life. To facilitate their interpretation, we are presenting them in two graphs (for pathologies with higher and lower incidence rates). Consistent with other publications, the common cold is the pathology with the highest incidence rate in both age intervals.

The present study recorded the prevalence of BF and the age at weaning; we did not collect data on exclusive BF, but on BF in general, and our data show rates that are better than those reported in the study performed in Asturias in 200010 both for establishing BF (80% compared to 72.7%) and for its prevalence at four months of age (45% versus 19.6%).

According to our data, BF is not a protective factor against infectious disease. This may be due to the fact that we recorded BF in general and not exclusive BF, and that we only analysed the data for the 6 to 12 month age interval.

As for family characteristics, a larger percentage of mothers than fathers had higher education degrees, and the mothers smoked less than the fathers. Only 6.5% of the children had two or more siblings.

The statistical analysis of the two cohorts (attending/not attending childcare) was performed on the data gathered for the age range between 6 to 12 months, since very few children enrolled in childcare at ages below five months.

In the population under study, 21.34% of children attended childcare by age 12 months, and the stated reason for it, in every case except for one, was the employment status of family members. In one case, the decision to send the child to childcare had to do with early socialisation.

When we calculated the RR of developing infectious pathologies in children who attended childcare, we did not take into account pathologies with incidence rates below 4%.

Childcare attendance may have caused from 35% to 50% of acute gastroenteritis, otitis, bronchiolitis, and bronchitis cases; figures similar to those reported in the systematic review “Relación entre la asistencia a guarderías y enfermedades infecciosas en la población infantil” published in 20077.

The low number of pneumonia episodes did not allow us to calculate whether attending childcare increased the risk of suffering this disease; perhaps the follow-up of both cohorts in the upcoming years will produce definitive data.

It is important that we not only know how attending childcare influences contracting the pathologies under study, but also how it influences the number of episodes suffered, so we calculated the difference between the cohort means, and found significant differences for several of these pathologies: bronchiolitis, bronchitis, conjunctivitis, gastroenteritis, acute otitis media, common cold, and wheezing. Still, the study of recurrent otitis in particular did not contribute definitive data; in accordance with the definition included in the consensus document on otitis media11, the presence of at least three episodes of otitis within six months was considered recurrent otitis. In the age range under study (6 to 12 months), only four children who did not attend childcare met these criteria (0.4%) presenting a maximum of four episodes, and among those who did attend childcare, another four met the criteria (3.4%), although they suffered a higher number of episodes, up to a total of eight in this span of time.

This project has been funded by OIB (Oficina de Investigación Biosanitaria / Biomedical Research Office) of the Principality of Asturias, and it is an adaptation to the region of Asturias of the study designed by the research group of the AEPap (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics) published under the title: “Influencia de la asistencia a las guarderías sobre la morbilidad y el consumo de recursos sanitarios en menores de 2 años”12.

Conclusions

- The percentage of children that attend childcare centres is similar to the percentage in the rest of Spain.

- The data gathered up to 12 months are consistent with previous studies in showing a higher incidence of infectious pathologies in absolute numbers, and in the infectious pathologies most prevalent in children that attend a childcare centre.

- The follow-up of both cohorts will complete the data presented in this study.

- The decision to send children to a childcare centre at an early age is associated with parental employment, and with maternity leave and BF breaks. Considering these results, it would be advisable that other means of caring for young children are sought, and that the duration of maternity leave and BF breaks are extended, as has been done in other EU countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful for the support received from the Unit of Statistical Consultancy of the Scientific and Technical Services of the University of Oviedo. They are particularly thankful for the support of Tania Iglesias Cabo. We also want to thank Guadalupe del Castillo Aguas for her contribution.

Research Group

Aidé Aladro Antuña, Ana M.ª Pérez López, Begoña Domínguez Aurrecoechea, Encarnación Díez Estrada, Francisco J. Fernández López, José I. Pérez Candás, Leonor Merino Ramos, María Fernández Francés, M.ª Ángeles Ordóñez Alonso, Purificación López Vilar, Sonia Ballesteros García.

Group of collaborators with the research project

Isabel González-Posada Gómez, Sonia Alonso Álvarez, M.ª Agustina Alonso Álvarez, Diana Solís, Diana Josefina Collao Alonso, Margot Morán Gutiérrez, Ángel Costales-Gloria Peláez, Mar Coto Fuente, Mónica Cudeiro Álvarez, José I. Pérez Candás, Beatriz Fernández López, Ana M.ª Pérez López, M.ª Pilar Flórez Rodríguez, Leonor Merino Ramos, Cruz Andrés Álvarez, Isolina Patallo Arias, Mónica Fernández Inestal, Ana Pérez Baquero, Carmen Díaz Fernández, Silvia Ruisanchez Díez, María Fernández Francés, Antonia Sordo, Sonia Ballesteros, M.ª Antonia Castillo, Begoña Domínguez, Lidia González Guerra, Águeda García Merino, Encarnación Díez Estrada, Teresa García, Francisco J. Fernández López, M.ª Teresa Cañón del Cueto, Purificación López Vilar, Laura Tascón Delgado, Isabel Tamargo Fernández, Laura Lagunilla Herrero, Susana Concepción Polo Mellado, Cruz Bustamante Perlado, Susana Parrondo, Nevada Juanes Cuervo, Ana Arranz Velasco, Belén Aguirrezabalaga González, Mario Gutiérrez Fernández, Isabel Mora Gandarillas, Rosa M.ª Rodríguez Posada, Isabel Fernández Álvarez-Cascos, Isabel Carballo Castillo, Felipe González Rodríguez, Tatiana Álvarez González, Zoa Albina García Amorin, Aidé Aladro Antuña, Monserrat Fernández Revilla, Fernando Nuño Martín, M.ª Ángeles Ordóñez Alonso.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest in relation to the preparation and publication of this paper.

This project has been funded by the OIB of the Principality of Asturias. There was no other source of funding for it.

ACRONYMS: PC: Primary Care • BF: breastfeeding • OIB: Oficina de Investigación Biosanitaria (Biomedical Research Office) • RR: relative risk • EU: European Union.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Población Activa. Módulo de conciliación entre la vida laboral y familiar [en línea] [consultado el 12/05/2012]. Disponible en www.ine.es/prensa/np417.pdf

- Pickering LK. Cuidados infantiles y enfermedades transmisibles. En: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB (eds.). Nelson Tratado de Pediatría, 17.ª ed. esp. Madrid: Elsevier; 2006.

- Ball TM, Holberg CJ, Aldous MB, Martínez FD, Wright AL. Influence of attendanceat day care on the common cold from birth through 13 years of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:121-6.

- Paradise JL, Rockette HE, Colbora DK, Bernard BS, Smith CG, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Otitis media in 2253 Pitsburg-area infants: prevalence and risk factors during the first two years of life. Pediatrics. 1997;99:318-33.

- Montiano Jorge J, Ocio Ocio I, Díez López I, Matilla Fernández A, Bosque Zabala A. ¿Qué pasaría si cerrasen las guarderías? An Pediatr (Barc). 2006;65(6):556-60.

- Lafuente Mesanza P, Lizarraga Azparren MA, Ojembarrena Martínez E, Gorostiza Garay E, Hernaiz Barandiarán JR. Escolarización precoz e incidencia de enfermedades infecciosas en niños menores de 3 años. An Pediatr (Barc). 2008;68:30-8.

- Ochoa Sangrador C, Barajas Sánchez MV, Muñoz Martín B. Relación entre la asistencia a guarderías y enfermedades infecciosas agudas en la infancia. Una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2007;81(2):113-29.

- Robinson J. Infectious Diseases in schools and child Care facilities. Pediatr Rev. 2001;33(2):39-46.

- Cano Garcinuño A, Mora Gandarillas I, Grupo SLAM. Patrones de evolución temporal de las sibilancias en el lactante. Bol Pediatr. 2012;52:86-7.

- Suárez Gil P. Prevalencia y duración de la lactancia materna en Asturias. Gac Sanit. 2000;15(2):104-10.

- del Castillo Martín F, Baquero Artigao F, de la Calle Cabrera T, López Robles MV, Ruiz Canela J, Alfayate Miguélez S, et al. Documento de consenso sobre etiología, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la otitis media aguda. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2012;14:195-205.

- del Castillo Aguas G, Gallego Iborra A, Ledesma Albarrán JM, Gutiérrez Olid M, Moreno Muñoz G, Sánchez Tallón R, et al. Influencia de la asistencia a las guarderías sobre la morbilidad y el consumo de recursos sanitarios en niños menores de dos años. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2009;11:695-708.