Vol. 27 - Num. 108

Original Papers

Analysis of knowledge and awareness of commercial determinants of health among pediatricians and pediatric residents in the province of Guipúzcoa

Enara Legarda-Ereño Riveraa, Ainhoa Zabaleta Ruedab, María Unsain Mancisidorc

aPediatra. CS Azkoitia. Guipúzcoa. España.

bPediatra. CS Pasaia San Pedro. Pasajes. Guipúzcoa. España.

cPediatra. CS Hernani. Guipúzcoa. España.

Correspondence: E Legarda-Ereño . E-mail: enara.legarda-erenorivera@osakidetza.eus

Reference of this article: Legarda-Ereño Rivera E, Zabaleta Rueda A, Unsain Mancisidor M. Analysis of knowledge and awareness of commercial determinants of health among pediatricians and pediatric residents in the province of Guipúzcoa . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:385-93. https://doi.org/10.60147/6201090a

Published in Internet: 10-12-2025 - Visits: 2162

Abstract

Introduction: commercial determinants of health (CDOH) is a term that refers to the activities and strategies of the private sector aimed at promoting products with an impact on people’s health. One example is the marketing of commercial milk formulas (CMFs), which targets both health care professionals and the general population, challenging the breastfeeding recommendations of the WHO and hindering adherence.

In 1982, the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (ICMBS) was established to protect families from the aggressive tactics of the CMF industry. However, violations of the Code occur frequently.

Material and Methods: a descriptive, observational study was conducted using a Google Forms questionnaire, with data analyzed using SPSS. Participants included primary care pediatricians, hospital pediatricians and pediatric residents of Gipuzkoa.

Results: we collected a total of 82 responses. Of all respondents, 56.1% worked in primary care, and approximately 25% were familiar with the concept of CDOH and the ICMBS. They rated the influence of the industry on their clinical activity with a median score of 4. All respondents had received gifts from the pharmaceutical industry, 97.5% the past year. In addition, 57% reported that they avoided displaying advertisements in their offices, although 80% currently had some form of advertisement. When it came to visits from industry representatives, 48.4% believed they interrupted their clinical activity, 60.9% reported that they delayed consultations and 50% had considered refusing them. Eighty-six percent of attending physicians received free samples of CMF (66% offered only hydrolyzed formula). Last of all, 90.2% reported that their first contact with a sales representative occurred during their medical residency training.

Conclusions: seventy-five percent of respondents were unaware of the concept of CDOH and the ICMBS, and current practices in Gipuzkoa continue to violate the Code's guidelines.

Keywords

● Advertisement ● Commercial determinants of health ● Infant formula ● MarketingINTRODUCTION

Commercial determinants of health (CDOHs) are the private sector activities that affect people’s health, directly or indirectly, positively or negatively. They influence the social, physical and cultural environments, promoting certain personal lifestyle habits and affecting the health of the population.

Commercial determinants of health impact a broad range of risk factors, including smoking, air pollution, alcohol use, obesity and physical inactivity or the promotion of formula feeding for infants and young children.1-3 This is a serious problem, since four industry sectors (tobacco, ultraprocessed foods, fossil fuels and alcohol) account for 33 million deaths a year, amounting to 78% of global deaths from noncommunicable disease.4 Commercial determinants of health contribute to economic and social inequities and affect everyone, but young people are especially at risk.

In the field of pediatrics, commercial determinants of infant and young child feeding, such as the influential marketing techniques used to promote commercial milk formula (CMF), have a particularly strong impact. It is well known that breast milk is the best possible food for a baby,5-7 with ample evidence of its benefits, so the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding (BF) through age 6 months and continued BF for at least the first two years of life.6

In the mid-20th century, companies promoted formula feeding by presenting infant formula as modern, scientific, prestigious and superior to human milk. Subsequently, companies intensified their marketing in low- and middle-income countries, using multiple tactics, even having their salespeople dress as health care workers to engage more persuasively with mothers at hospitals and in their homes.5 Owing to the use of aggressive marketing strategies, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, BF initiation rates in the United States had dropped to 25%. This means that an entire generation of new families, who are now grandparents and health care professionals, experienced a status quo in which most babies were fed infant formula.8

As a result of the increase in formula feeding (and the decrease in BF), infant mortality increased in countries with limited access to clean water,5 and there is evidence of an association between the use of CMF and malnutrition, morbidity and mortality in children, which is known as comerciogenic malnutrition.7

In 1981, the World Health Assembly published and adopted the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (ICMBS) with the aim of protecting families from the aggressive tactics of the CMF industry. The Code seeks to protect all mothers and their babies from inappropriate practices in the marketing of CMF by prohibiting widespread strategies such as promotion through advertising posters or gifts targeting health care professionals, families or health care institutions.9 Currently, the commercial activity of CMF manufacturers includes, in addition to conventional practices, the use of digital platforms and individual data to implement increasingly personalized and targeted marketing strategies, substantially expanding their influence and reach.10 The ICMBS is a set of nonbinding recommendations7 and, while some countries have passed legislation to implement the code in its entirety, only a few of its provisions have been incorporated in Spanish law.11 Since the Code is not legally binding, it is not enforceable and compliance with its recommendations continues to be poor 40 years after its creation.5 Moreover, since the development of the first commercial infant formula in 1865, the sale of these products has only grown, with global CMF sales growing 37-fold between 1978 and 2019 (from US$1.5 billion to US$55.6 million annually).5,7

One of the strategies devised by the CMF industry has been the broadening of the target market for CMF by expanding from a single infant formula product category to three (stages 1-3, or starter formula, follow-on formula and toddler/growing-up milk). Since most of the provisions of the Code focus on starter or stage 1 formula (age 0-6 months), the diversification of CIFs allows cross-promotion of entire product ranges, thereby circumventing marketing regulations that could be interpreted as applying solely to infant formula.7

The expansion has also involved a widening of the perceived boundaries of diet-related infant and young child illness through the overdiagnosis of conditions such as cow's milk protein allergy and the pathologization of typical infant or young child behaviors, such as fussiness, gas or crying, to induce demand for so-called specialized formulas claimed to have therapeutic benefits for these purported ailments.7

In Spain, Royal Decree 1416/1994 of June 2512 regulating the advertisement of medical products for human use Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 of July 24,13 enacting the consolidated text of the Law on guarantees and rational use of medicines and health products, are the laws currently regulating the advertising of medicinal products and the relationship between health care providers and industry. However, this regulatory framework is somewhat meager, as it only addresses situations that are “not insignificant”.14

It is important to be aware that health care professionals may become, even if unintentionally, a gateway allowing the interests of industry to reach families,5 so they are a key target for the pharmaceutical industry. However, they are also in a privileged position to drive transformative change for, as Friel et al. noted,15 health care professionals can and should leverage their credibility and authority to exert influence over CDOHs, underscoring the importance of prevention and, consequently, protecting child health.

For all the above reasons, we decided to conduct a study with the primary objective of investigating the knowledge and awareness of CDOHs among pediatricians and pediatric residents (in the medical intern-resident [MIR] program) in Gipuzkoa. The secondary objectives were to assess the knowledge and implementation of the ICMBS, to describe the relationships of pediatricians with pharmaceutical industry representatives and to analyze the characteristics of their interactions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted an observational, descriptive study using a Google Forms questionnaire consisting of 35 items covering various topics, such as awareness of CDOHs, visits of pharmaceutical sales representatives to health care facilities, knowledge of and implementation of the ICMBS and healthy diet. The questionnaire was developed by the authors and subsequently distributed by the principal investigator, who submitted the link in an explanatory email sent to the main department heads in the three hospitals in the province of Gipuzkoa. They, in turn, shared the link via their mailing lists with hospital pediatricians and primary care pediatricians in their respective regions.

Participants completed the questionnaire on an anonymous and voluntary basis.

The data were collected and analyzed with the software package SPSS. Respondents included primary care (PC) pediatricians, hospital-based pediatricians and pediatric residents in the province of Gipuzkoa.

RESULTS

We received 82 responses from a total of 177 registered pediatricians and 30 pediatric residents (response rate of 39.6%)

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample.

| Table 1. Characteristics of the sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 18 | 22% |

| 30-40 | 28 | 34.1% |

| 40-50 | 20 | 24.4% |

| 50-60 | 12 | 14.6% |

| >60 | 4 | 4.9% |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 70 | 85.4% |

| Male | 12 | 14.6% |

| Care setting | ||

| Primary care | 46 | 56.1% |

| Hospital | 19 | 23.2% |

| Pediatric residency (MIR) | 17 | 20.7% |

| Work experience | ||

| <5 years | 26 | 31.7% |

| 5-10 years | 14 | 17.1% |

| 10-20 years | 22 | 26.8% |

| >20 years | 21 | 25.6% |

Of all respondents, 24.4% were familiar with the concept of CDOHs and 11% knew what they were. When it came to the ICMBS, 25% knew about it and 15.8% had heard of it. Most respondents believed that the industry influenced their clinical practice, rating this influence at a median [IQR] of 4 [2-6] points (on a scale from 1 to 10), and 21.7% thought that advertising (on television, the internet, etc.) had some influence on the recommendations they made to patients.

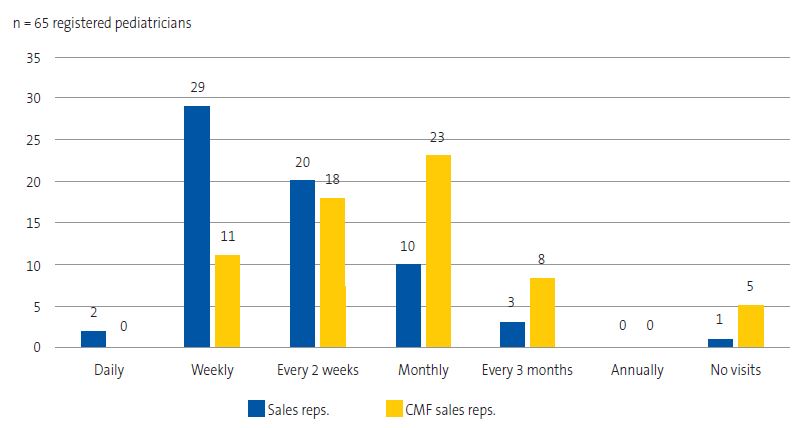

In addition, 98.5% of attending pediatricians (n = 65) received visits from pharmaceutical sales representatives. One pediatrician responded that she did not accept these visits. The questionnaire also asked about the characteristics of these visits (Table 2). Thirty-one pediatricians had considered refusing visits from sales representatives on occasion, and 17 of them had even proposed this to their colleagues. Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of these visits.

| Table 2. Characteristics of sale representative visits to registered pediatricians (n = 65) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) |

| Received visits | 64 (98.5%) |

| Met representatives in office | 54 (83.1%) |

| Met representatives in hallway | 4 (6.1%) |

| Met representatives in a prearranged space | 4 (6.1%) |

| Met representatives outside the facility | 1 (1.5%) |

| Met representatives by appointment | 13 (20%) |

| Felt obligated to interrupt clinical work to meet representatives | 31 (47.7%) |

| Considered they caused delays in clinical work | 39 (60%) |

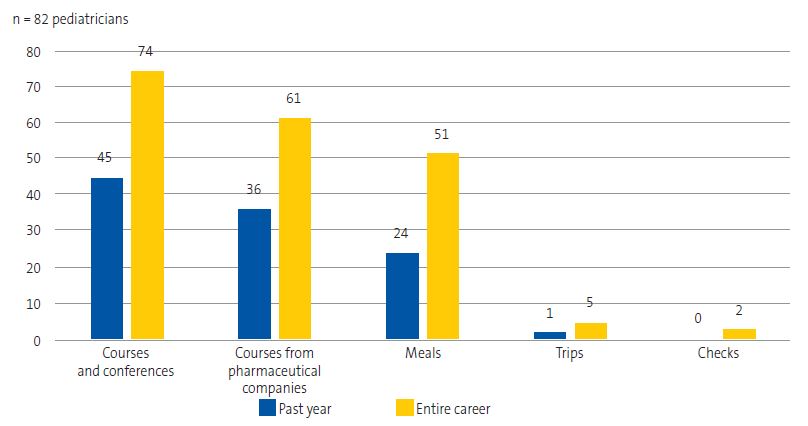

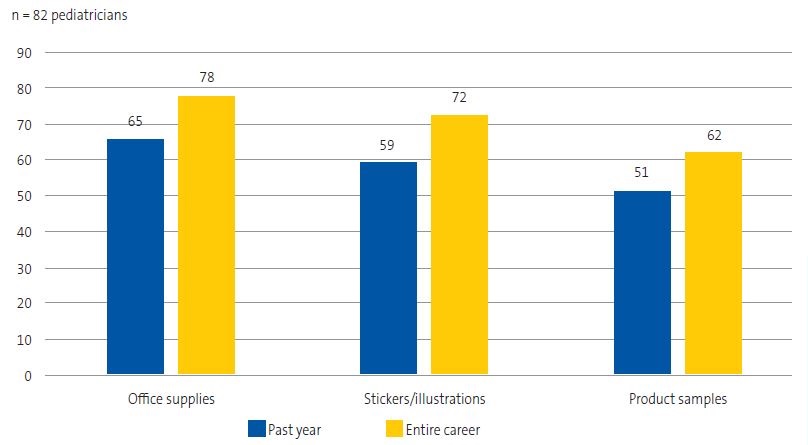

All of the respondents had received gifts or incentives from the pharmaceutical industry in the course of their professional careers, and 97.5% had received them in the past year. Figure 2 describes the gifts or incentives for personal use and Figure 3 the gifts for patients and for use in the care setting received by respondents.

| Figure 2. Gifts or incentives for personal use received by respondents in the past year and throughout their medical careers |

|---|

|

| Figure 3. Gifts for patients or for use in the clinic/hospital received by respondents in the past year and throughout their medical careers |

|---|

|

Fifty-seven percent of respondents believed that they avoided displaying any form of advertisements in their offices; however, up to 80% had some item that featured advertising in the office at the time of participation in the survey.

Fifty-six registered pediatricians reported receiving free samples of CMF. Of these, 12.5% did not offer these samples to families; 17.9% offered only hydrolyzed milk and formulas for so-called functional gastrointestinal disorders and 3.5% offered all types of formulas. The majority (66%) offered only hydrolyzed milk.

In addition, 23.1% of respondents reported receiving advertising for other products, such as food products, soft drinks, custards, purées or cookies. In addition, 7.3% had requested free cookie samples, all of them stating that they had requested them for personal use.

Twenty-one percent of participating pediatricians worked in health care facilities that had vending machines.

The questionnaire also explored the reasons why health care professionals accepted or rejected visits from pharmaceutical sales representatives. The main reasons for rejecting visits were the interruption or delay of care delivery (n = 14), receiving repetitive or unnecessary information (n = 7), ethical reasons (n = 4) or overly familiar or aggressive behavior on the part of sales representatives (n = 3). On the other hand, the main reasons for continuing with these visits were receiving updates on their products (n = 13), respect for the work of sales representatives (n = 9), the possibility of future funding (n = 4) or the development of a personal relationship with sales representatives (n = 2).

The questionnaire also explored how pediatricians perceived a series of food products, given the potential influence of CDOHs. To this end, respondents were asked to rate each food from 1 to 10 according to how healthy they thought it was ( 1: unhealthy, 10: very healthy). Table 3 summarizes these ratings.

| Table 3. Ratings given to food products sold in supermarkets | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Mean rating (SD) | Product | Mean rating (SD) |

| Plain “Maria” cookies | 2.5 (1.74) | Fresh juice | 5.7 (2.29) |

| Sugar-free cookies | 3.04 (2.12) | Packaged juice | 1.59 (1.38) |

| Gluten-free cookies, muffins… | 3.46 (2.48) | Orange | 9.76 (1.09) |

| Chocolate cereal | 2.27 (1.94) | Baby fruit purée | 4.83 (2.72) |

| Plain yogurt | 8.68 (1.56) | Fat-free milk | 6.18 (2.52) |

| Flavored yogurt | 3.8 (2.16) | Whole milk | 8.87 (1.6) |

| Yogurt with fruit chunks | 4.67 (2.49) | Stage 3 formula | 5.44 (2.5) |

| Custard | 2.46 (1.8) | Stages 1, 2 formula | 7.99 (1.88) |

| Broccoli | 9.72 (1.23) | Powdered chocolate milk blends (such as Cola Cao) | 1.93 (1.48) |

| Cooked ham (cold cuts) | 4.59 (2.02) | Sugar-free pure cocoa powder | 6.15 (2.26) |

| Soda | 1.28 (1.17) | ||

| SD: standard deviation. | |||

Of all respondents, 85.4% reported reading the labels of food products before recommending them.

The exposure to CDOHs begins during the residency period (MIR program): 90.2% of respondents had their initial contact with a sales representative during the residency. In addition, 22% reported they were overtly or indirectly directed to recommend specific CMFs during their residency based on brands they had seen in the hospital, gifts received from the industry, pre-established formula feeding protocols in the hospital or agreements with pharmaceutical companies, among other possible reasons. Therefore, 92.7% of respondents stated that the residency curriculum should include further education on CDOHs.

DISCUSSION

Only 24.4% of surveyed pediatricians were familiar with the concept of CDOH. This is to be expected based on the article series recently published by The Lancet (2023),4,5,7 which reflects that there is still no clear and widely accepted definition of CDOHs. However, the fact that only 25% of respondents knew the ICMBS was striking, given how long it has been in place and the circumstances that motivated its creation.

In light of their own responses, it was surprising to find the extent to which pediatricians believed that the pharmaceutical industry had little influence on their clinical practice. This was consistent with the review published by Fickweiler et al.,16 which revealed that most physicians believed that their interactions with the pharmaceutical industry and sales representatives did not impact their behavior.

With regard to the characteristics of sales representative visits, it is striking that only one respondent refused to meet them, considering that up to 47.7% of respondents felt obligated to interrupt patient care and 60% that meeting with them resulted in delayed appointments. This ambivalence is also reflected in a study conducted in France published in 202217: practitioners kept meeting pharmaceutical sales representatives in spite of their unfavorable opinion of the pharmaceutical industry. In that study, as in ours, the main reason for continuing to meet them was needing information about their products.

Pediatricians received frequent visits, mostly on a monthly or weekly basis. This differs from the data reported in a 2007 audit conducted in the United Kingdom, in which fewer than 5% of respondents had been visited by CMF company representatives in the past 6 months.

Accepting gifts from pharmaceutical sales representatives or meeting them is correlated with excessive, more expensive and sometimes less rational prescribing.17 As our survey demonstrates, pediatricians in Gipuzkoa continued to receive gifts (97.5% in the last year): mainly funding for courses and conferences, or trainings organized by the pharmaceutical company itself, as well as business lunches and dinners. Payments for leisure travel and checks did not appear to be common at the time of the survey, but they were among the gifts previously offered by the pharmaceutical industry. Gifts for patients and office supplies were also common: most respondents had received office supplies, stickers, illustrations or similar products. In the audit conducted in the United Kingdom by McInnes et al.,18 most respondents (20.5% of the sample) received a range of literature from CMF companies and few received advertising through gifts or funding (only 7%). Receiving gifts and other incentives, given their potential influence, raises ethical questions.19

Although it directly contravenes the ICMBS, sales representatives continued to offer free CMF samples to pediatricians in primary care centers and hospitals, and 86% of respondents accepted them. Our findings were similar to those of a study conducted in the United States in which 90% of providers accepted free samples.20 However, in the audit conducted by McInnes et al.18, only three out of 669 practitioners accepted free CMF samples, which raises the question of why such large differences exist. In our study, we found that pediatricians chiefly offered samples of hydrolyzed formula, so it would be interesting to explore the situations in which such samples are offered to families in future studies. Offering free samples results in cross-promotion of other types of CMF, as manufacturers employ the tactic of using similar formats and colors for different types of formula.21. Cross-promotion is also achieved through other advertising materials present in the care setting.21 One of the salient findings in our study was that while 57% of respondents were aware of the need of avoiding any form of advertising in the office, up to 80% had some form of advertising material in the office at the time of the survey. In the audit conducted by McInnes et al.18, CMF advertising materials were present in 33% of the clinics, so there is ample room for improvement in Gipuzkoa.

The questionnaire directed pediatricians to rate different types of foods due to the potential influence of CDOHs. Their opinions regarding CMFs was particularly interesting. On the one hand, they gave very positive ratings to stage 1 and 2 formulas (7.99), which was striking compared to the ratings given to stage 3 formula (growing-up milk). The latter received a mean rating of 5.44, although with a wide standard deviation, indicating that there was more disagreement in the ratings given by different doctors. Current guidelines recommend continued BF or, in its absence, consumption of cow's milk after the first year of life. The industry offers growing-up milk as an alternative; however, these products contain large amounts of sugars, sweeteners, and vegetable fats, so there could be a relationship between the relatively high ratings they received and the marketing of these products by the CMF industry.

The interaction with the pharmaceutical industry and sales representatives begins early in physicians’ careers, as they are exposed to the pharmaceutical industry's marketing and promotion techniques from the residency period, with a potential impact on their future prescribing behavior.16 In our survey, 90.2% of respondents had their first contact with a sales representative during the residency. In general, residents are more vulnerable to interactions with the pharmaceutical industry compared to more experienced physicians, so it is important to implement educational interventions to raise awareness,16 a need expressed by 92.7% of respondents.

Among the strengths of the study are its efficiency and reproducibility. We used free tools and simple methods that could be easily reproduced in similar studies. Another strength is the relevance of the subject matter, which has attracted growing interest in recent years. Its importance extends beyond pediatrics to medicine in general, making it a suitable framework for studies in other medical specialties.

One of the main limitations of the study was the use of an online questionnaire accessed through a link. Despite the acceptable response rate (39.6%), it is likely that several pediatricians did not receive this link. This distribution strategy also carries a risk of selection bias, as the pediatricians who chose to respond could have been those most familiar with the problem. In addition, the study was conducted in a single province, so, in the future, it would be interesting to extend research on this subject to other provinces and autonomous communities.

CONCLUSIONS

After analyzing the results of the survey, we drew the following conclusions:

- Few pediatricians in Gipuzkoa were familiar with the concept of CDOH or the ICMBS.

- At present, the recommendations included in the ICMBS continue to be violated in the province of Gipuzkoa.

- Although most pediatricians in Gipuzkoa had negative perceptions of pharmaceutical sales representative visits, few actually refused them.

- Many of the surveyed pediatricians believed that advertising and their interactions with the pharmaceutical industry had little impact on their practice, and many considered that they were able to avoid the display of advertising materials in the settings where they worked, but few actually did.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

Author contributions: development and dissemination of questionnaire, manuscript writing (ELER), development of questionnaire, manuscript writing (AZR, MUM).

A summary of this study was presented at the 21st Congress of the AEPap, held in Madrid on 21/02/2025. However, this article provides more detailed and comprehensive information.

ABBREVIATIONS

BF: breastfeeding · CDOH: commercial determinants of health · CMF: commercial milk formula · ICMBS: International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes · PC: primary care.

REFERENCES

- Kickbusch I, Allen L, Franz C. The commercial determinants of health. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(12):e895-6.

- Commercial determinants of health. In: WHO [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health

- Maani N, Collin J, Friel S, Gilmore AB, McCambridge J, Robertson l, et al. Bringing the commercial determinants of health out of the shadows: a review of how the commercial determinants are represented in conceptual frameworks. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(4):660-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz197

- Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, Bertscher A, Bondy K, Chang HJ, et al. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1194-213.

- Rollins N, Piwoz E, Baker P, Kingston G, Mabaso KM, McCoy D, et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. The Lancet. 2023;401(10375):486-502.

- Pérez-Escamilla R, Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Baker P, Barros AJD, Bégin F, et al. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. The Lancet. 2023;401(10375):472-85.

- Baker P, Smith JP, Garde A, Grummer-Strawn LM, Wood B, Sen G, et al. The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress. The Lancet. 2023;401(10375):503-24.

- Kellams A. Breastfeeding: Parental education and support. In: UpToDate [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.uptodate.com/contents/breastfeeding-parental-education-and-support

- ¿Qué es el código internacional de comercialización de sucedáneos de leche materna? In: Familia y Salud [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.familiaysalud.es/vivimos-sanos/lactancia-materna/leche-materna-la-decision-mas-acertada/que-es-el-codigo#:~:text=Es un conjunto de reglas,aquellas madres que lo deseen

- Asociación IHAN, Unicef. Código Internacional de Comercialización de Sucedáneos de la Leche Materna [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. In: iHAN. Available at www.ihan.es/codigo-internacional-de-comercializacion-de-sucedaneos-de-leche-materna/

- Food & Nutrition Action in Health Systems (AHS), Nutrition and Food Safety (NFS). Marketing of breast-milk substitutes: national implementation of the International; 2024. In: WHO [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240094482

- Real Decreto 1416/1994, de 25 de junio, por el que se regula la publicidad de los medicamentos de uso humano. In: BOE [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1994/06/25/1416

- Real Decreto Legislativo 1/2015, de 24 de julio, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley de garantías y uso racional de los medicamentos y productos sanitarios. In: BOE [online] [accessed 28/11/2025]. Available at www.boe.es/eli/es/rdlg/2015/07/24/1

- Verdú González I. A la búsqueda del médico bueno: los conflictos de intereses en las relaciones con la industria farmacéutica. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.6018/bioderecho.458841

- Friel S, Collin J, Daube M, Depoux A, Freudenberg N, Gilmore AB, et al. Commercial determinants of health: future directions. The Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1229-40.

- Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408

- Barbaroux A, Pourrat I, Bouchez T. General practitioners and sales representatives: Why are we so ambivalent? PloS One. 2022;17(1):e0261661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261661

- McInnes RJ, Wright C, Haq S, McGranachan M. Who’s keeping the code? Compliance with the international code for the marketing of breast-milk substitutes in Greater Glasgow. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(7):719-25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007441453

- Khazzaka M. Pharmaceutical marketing strategies’ influence on physicians’ prescribing pattern in Lebanon: ethics, gifts, and samples. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3887-6

- Werner KM, Mercurio MR, Shabanova V, Hull SC, Taylor SN. Pediatricians’ Reports of Interaction with Infant Formula Companies. Breastfeed Med. 2023;18(3):219-25. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2022.0217

- Ng WC, Yeung KHT, Hui LL, Chow KM, Lau EYY, Nelson EAS. A Content Analysis of Digital Marketing Strategies of Formula Companies and Influencers to Promote Commercial Milk Formula in Hong Kong. Matern Child Nutr. 2025;21(3):e70007. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.70007