Vol. 27 - Num. 108

Original Papers

Connected to recommendations on screen use? A parent survey study

Elena Sánchez Marcos

aServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada. Fuenlabrada. Madrid. España.

bGraduada en Medicina. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Madrid. España.

cMIR-Pediatría. Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada. Fuenlabrada. Madrid. España.

Correspondence: E Sánchez. E-mail: elenasanmar1092@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Sánchez Marcos E, Cotoli Pribylovab M, Domingo Comeche L, Egido García-Comendador R, Zafra Anta MA. Connected to recommendations on screen use? A parent survey study . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:361-70. https://doi.org/10.60147/c802efb9

Published in Internet: 29-10-2025 - Visits: 7244

Abstract

Introduction: screen use during childhood has been associated with negative effects in several areas such as neurodevelopment and mental health. The Spanish Association of Pediatrics developed a series of recommendations to promote appropriate use of electronic devices. The primary objective was to assess adherence to these recommendations in a sample of children aged 0 to 12 years. Secondary objectives included analyzing the influence of sociodemographic factors on adherence and evaluating parental perceptions.

Methods: observational and descriptive study conducted in the Department of Pediatrics of the Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada through the administration of a questionnaire to parents of children aged 0 to 12 years.

Results: a total of 448 responses were obtained. The mean age of the children was 6.5 years (SD 3.83), and 45.98% were girls. Only one in four families adhered to at least 80% of the recommendations. Adherence was higher among families with children aged 6 to 12 years (OR 3.64, 95% CI 1.60–8.26), those with at least one parent with higher education (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.60–8.26), those who were aware of the recommendations (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.36–3.63), and those who considered themselves good role models (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.23–2.94). Notably, 70.54% reported not having received any information from a health care professional.

Conclusions: adherence to the recommendations is inconsistent and generally suboptimal. Overall, the findings highlight the need to improve the information provided to families, promoting conscious and appropriate screen use from early childhood.

Keywords

● Digital health ● Health promotion ● Screen time ● Socioeconomic factorsINTRODUCTION

At present, children are exposed to electronic devices from an early age. In some respects, the moderate use of these devices under supervision can be beneficial.1 However, excessive or inappropriate use has been associated with potential deleterious effects. With respect to neurodevelopment, screen use has been associated with delayed language development, difficulties in self-regulation and poorer academic performance.1-4 Prolonged exposure is associated with sedentary lifestyle habits, sleep disturbances and an increased risk of childhood obesity.5,6. There is also evidence of an association with mental health problems, aggressive behavior and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.1,2,7

In this context, digital wellness, defined as the healthy, safe, critical and responsible use of information and communication technologies, becomes an important concept.5

On the other hand, there is also evidence of an association between parental screen use and lack of parental supervision with an increase in the risks derived from the use of electronic devices.8 Two studies conducted in Spain9,10 evince the influence of cultural and socioeconomic factors in screen use as well as the perception of its impact on health.

In 2023, to offer guidance to families, the Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP, Spanish Association of Pediatrics) launched the Family Digital Plan (FDP; in Spanish, “Plan Digital Familiar”),11 a tool aimed at promoting the safe use of technology, active parental supervision and parental modeling of appropriate use. It includes general and age-specific recommendations. Up to December 2024, the recommendations of the AEP regarding the maximum daily screen time for children were:

- Age < 2 years: “zero” screen time.

- Age 2 to 5 years: no more than 1 hour/day.

- Age 6 to 12 years: maximum of 2 hours/day.

In December 2024, the AEP issued a statement announcing changes to these recommendations.12 The most important change involved the maximum screen time recommended for children, extending the recommendation of “zero screen time” until age 6 years and reducing the maximum recommended to one hour a day for children aged 7 to 12 years.

Given the importance of the potential harmful effects of early exposure to screens and the concern expressed by pediatric scientific societies, we conducted a study with the primary objective of determining what proportion of children between the ages of 0 and 12 complied with the AEP recommendations on the use of electronic devices.

The secondary objectives included analyzing screen use by age group, studying the influence of sociodemographic factors, exploring family perceptions of screen use impact and evaluating the knowledge of families and the information received about the AEP recommendations.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a single-center, cross-sectional, observational study in the Department of Pediatrics of the Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada (Madrid).

The data were collected between November 2024 and February 2025 via an ad hoc questionnaire consisting of 62 items that was validated in terms of content and comprehensibility by a group of six experts with experience in survey design and piloted on a sample of ten families prior to the start of data collection. The questionnaire included a general section and a specific section for each age group (0 to 2 years, 3 to 5 years, and 6 to 12 years). It was aimed at parents of children who visited the outpatient clinics or pediatric emergency department of the hospital or were admitted to the pediatrics ward.

The questionnaire was developed in the Google Forms platform and could be accessed via a QR code distributed through posters and informational leaflets.

The questionnaire included questions regarding adherence to the AEP screen use recommendations. Some items were answered on a dichotomous (yes/no) scale, such as “Do you have parental control measures in place on the devices your child uses?”; and others using a Likert scale (always, frequently, sometimes, rarely, never) such as “Do you eat while watching television?” Families who answered either “always” or “often” or, depending on the meaning of the question, “never” or “rarely”, were considered to adhere to the recommendation, while those who had chosen the other answers were considered not to adhere to the recommendation.

The cut-off point for “adequate” adherence was set at 80% of the recommendations that participants were asked about. We chose this cut-off point because we considered reasonable for families to adhere to at least 12 of the 15 recommendations included in the questionnaire, understanding that greater compliance would be exceptional.

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital de Fuenlabrada. The sample consisted of children aged 0 to 12 years whose parents or guardians agreed to participate and provided consent for the use of the data obtained on an anonymous basis. Children aged 13 years or older, those who refused to participate, and those who had completed the survey in the past were excluded.

We estimated that the minimum sample size to assess the degree of adherence to the recommendations in the population of children aged 0 to 12 years in Fuenlabrada with a margin of error of ±5% and a 95% level of confidence was of 398 participants. The statistical analysis was performed with the Stata 16 software package.

RESULTS

We received 448 responses. Three age groups were established: 0 to 2 years, 3 to 5 years, and 6 to 12 years. Table 1 summarizes the main sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample n = 448 |

Age 0-2 years n = 98 |

Age 3-5 years n = 122 |

Age 6-12 n = 228 |

|

| Age of child (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.5 (3.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 4.7 (3.6) | 9.78 (2.0) |

| Sex of child | ||||

| Female – n (%) | 206 (46.0%) | 36 (36.8%) | 58 (47.5%) | 112 (49.1%) |

| Parental age (years) | ||||

| Mother – Mean (SD) | 40.2 (5.9) | 34.9 (4.7) | 37.8 (5.0) | 42.9 (4.9) |

| Father – Mean (SD) | 41.9 (6.5) | 36.5 (5.4) | 39.9 (6.0) | 44.7 (5.4) |

| Mean of both parents (SD) | 41.1 (6.0) | 35.7 (4.6) | 38.4 (5.1) | 43.9 (4.9) |

| Monthly household income | ||||

| Low (€<2000/month) – n (%) | 94 (20.9%) | 25 (25.5%) | 24 (19.8%) | 45 (19.7%) |

| Medium (€2000–3000/month) – n (%) | 120 (26.8%) | 31 (31.6%) | 33 (27.0%) | 56 (24.6%) |

| High (>€3000/month) – n (%) | 126 (50.4%) | 40 (40.8%) | 61 (50.0%) | 125 (54.8%) |

| Maternal educational attainment | ||||

| Basic (No schooling, PEd) ─ n (%) | 19 (4.0%) | 4 (4.1%) | 4 (3.3%) | 11 (4.8%) |

| Medium (ESO, Bachillerato, vocational education) – n (%) | 146 (32.6%) | 40 (41.8%) | 40 (32.8%) | 66 (29.4%) |

| Higher (University) – n (%) | 278 (62.1%) | 54 (54.1%) | 75 (61.5%) | 149 (64.9%) |

| Paternal educational attainment | ||||

| Basic (No schooling, PEd) ─ n (%) | 35 (7.6%) | 4 (4.1%) | 13 (10.6%) | 18 (7.9%) |

| Medium (ESO, Bachillerato, vocational education) – n (%) | 208 (46.4%) | 56 (57.1%) | 61 (50%) | 91 (39.9%) |

| Higher (University) – n (%) | 196 (43.7%) | 36 (36.7%) | 46 (37.7%) | 114 (50.0%) |

|

Bachillerato: noncompulsory secondary education (years 11-12); ESO: compulsory secondary education (years 7-10); PEd: primary education (years 1-6); SD: standard deviation. |

||||

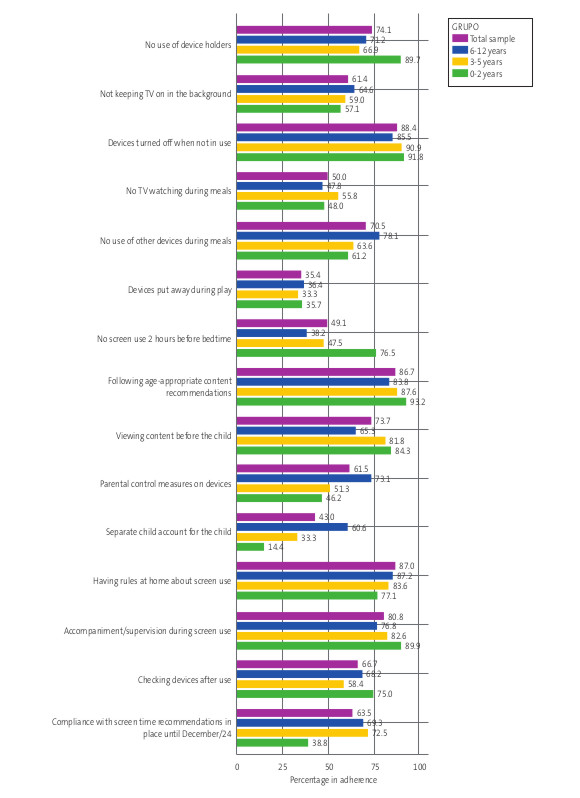

The questionnaire referred to 15 of the recommendations included in the FDP. Figure 1 shows the percentage of participants that adhered to these recommendations, both overall and by age group.

| Figure 1. Percentage of adherence to recommendations included in questionnaire (for total sample and by age group) |

|---|

|

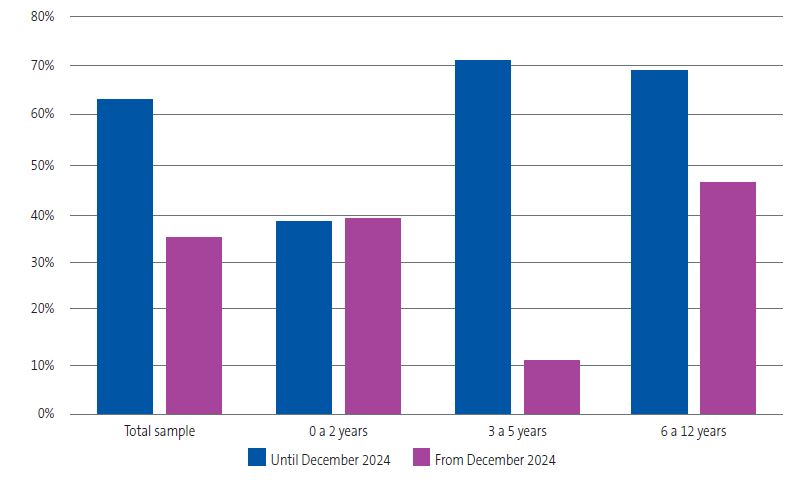

Figure 2 compares the degree of adherence to the recommendations for maximum daily screen time before and after the change introduced by the AEP in December 2024.

| Figure 2. Adherence to maximum daily screen time recommendations in place before and after the December 2024 statement by the AEP, which further restricted recommended screen times. Data for the total sample and for each age group |

|---|

|

With regard to adherence to at least 80% of the recommendations the questionnaire asked about, only one-fourth (24.8%) of the total sample achieved this percentage. In the 6-12 years group, almost one-third (32.9%) complied, compared to 24.5% in the 3-5 years group, while the percentage dropped to 11.2% in the youngest children.

To study the variable “adherence to at least 80% of the recommendations included in the questionnaire” in the different age groups, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders (mean age of both parents, monthly household income, and higher education in either parent), finding that children aged 6 to 12 years were 3.64 times more likely (OR: 3.64; 95% CI: 1.60 to 8.26; p = 0.002) to comply with at least 80% of the recommendations compared to children aged 0 to 2 years.

We explored other factors that could influence the frequency of adherence to 80% or more of the recommendations. Table 2 presents the analyzed factors and their statistical significance. The mean parental age was identified as a protective factor with borderline significance (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.11; p <0.001), indicating that adherence increased with parental age.

| Table 2. Association of different variables with adherence to at least 80% of recommendations the questionnaire asked about | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adherence to ≥80% of recommendations) n (%) |

OR (95% CI) |

p value | |

| At least one parent with higher education | Yes | 86 (28.9%) | 2.05 (1.25 to 3.38) |

0.005 |

| No | 25 (16.6%) | |||

| Knows about AEP recommendations | Yes | 85 (29.8%) | 2.22 (1.36 to 3.63) |

0.001 |

| No | 26 (16%) | |||

| Household income | High | 67 (29.6%) | 0.56 (0.31 to 1.01) |

0.04* |

| Medium | 23 (19.2 %) | |||

| Low | 18 (19.1%) | 1.01 (0.50 to 1.98) |

0.99* | |

| Has been informed by a professional | Yes | 37 (28.9%) | 1.33 (0,84 to 2,11) |

0.231 |

| No | 74 (23.4%) | |||

| Considers oneself a good role model for the child | Yes | 56 (32.6%) | 1.89 (1.23 to 2.94) |

0.003 |

| No | 55 (20.1%) | |||

|

*Association not significant for comparison of high vs low and medium vs low income. |

||||

Of all respondents, 63.6% stated that they were aware of the AEP recommendations, but almost three out of four (70.5%) answered 'no' when asked if a health care professional had ever discussed the recommendations with them. Only 38.4% said they felt they were good role models for their children when it came to screen use.

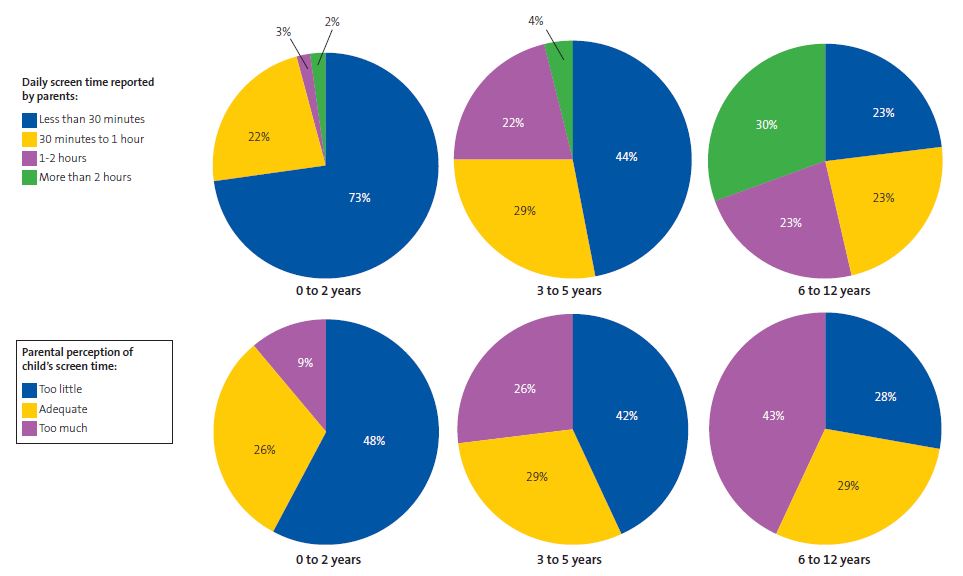

Figure 3 shows the average daily screen time reported by parents for their children, as well as how the parents perceived it.

| Figure 3. Mean child’s daily screen time reported by parents and parental perception of the child’s screen time by age group |

|---|

|

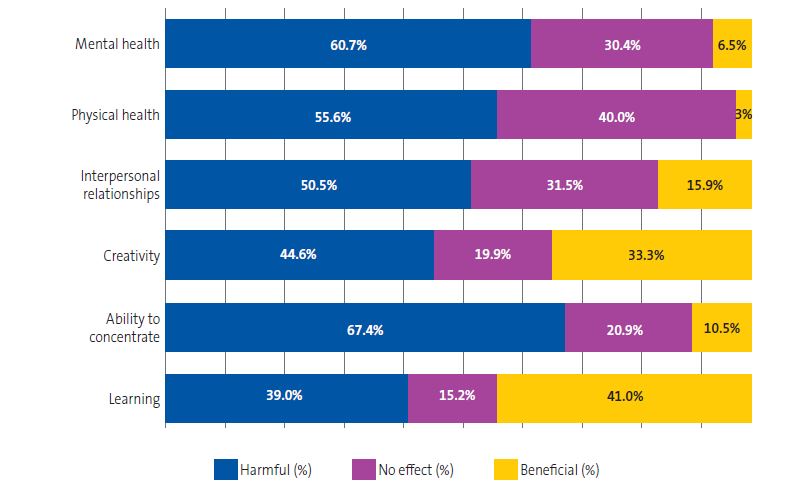

The questionnaire asked a series of questions about how parents felt electronic device use affected certain aspects of their children's development or health. The responses are summarized in Figure 4.

| Figure 4. Parental perceptions of the impact of electronic devices on different areas of their children’s lives |

|---|

|

A high proportion of families who completed the survey (84.0%) reported having screen use rules at home, most frequently (88.8%) involving time limits, followed by content restrictions (74.3%) and set screen-free times, such as meals or homework (59.6%). Most said that these rules were followed “always” or “often” (86.1%).

Of the older age group (6 to 12 years), 27.6% of children had a mobile phone of their own with internet access, with acquisition of the first phone at a mean age of 10.05 years (SD: 2.27 years). Within this subset, 71.4% had parental control measures set for the device. In addition, 89.5% reported they had talked to their children at some point about the dangers of the digital world. One in three (34.2%) had explicitly discussed sexual relationships with their children, given the possibility that they accidentally or intentionally access adult content.

DISCUSSION

Our study clearly shows the inconsistent adherence to the recommendations of the Family Digital Plan of the AEP. Applying the threshold defined by adherence to 80% or more of the recommendations included in the questionnaire, the figures are indisputably low, with one-fourth of respondents reaching that percentage.

The root cause of this irregular compliance is probably the excessive screen time. A meta-analysis from 202213 found that only 24.7% of children aged less than 2 years and 35.6% of children aged 2 to 5 years complied with daily screen time guidelines, with an increasing trend in screen time. If we were to take the recommendations of the AEP through December 2024 as reference, adherence would be much higher, especially among children aged 2 to 6 years. However, when considering current recommendations, adherence was adequate in only 1 in 10 children in this age range.

Regarding daily screen time, in the 6-12 years group, 30% reported screen time in excess of 2 hours a day, and, within this subset, only 4.9% reported screen times greater than 4 hours. In the United States, a survey was conducted in 2021 with participation of more than 1300 children aged 8 to 18 years.14 This survey found a mean screen time of 5.5 hours in children aged 8 to 12 years. In adolescents, screen time increased to 8 hours and 40 minutes. Similarly, in Spain, a study conducted by UNICEF8 showed that 30% of adolescents used electronic devices for more than 5 hours a day. Therefore, trying to reduce screen time in young children seems reasonable as a way to prevent excessive screen use at older ages.

We found a discrepancy between actual screen time and families' perceptions of it; in the 0-2 years and 3-5 years age groups, families tended to consider screen use in excess of the recommended level—which would be “zero”—as “low.” This can make hinder the implementation of preventive measures at home, as excessive screen use may not be perceived as a problem. On the other hand, on a positive note, parents of older children seemed to be more aware of and have a more critical approach toward daily screen time.

In a more detailed analysis of the recommendations addressed in our survey, putting devices away while playing with children and not watching television during meals were the recommendations for which adherence was lowest in every age group. The percentage that adhered to the recommendation to avoid screen use in the two hours preceding bedtime was less than 50% in every age group except the youngest. This reflects the extent to which devices are integrated into daily routines, making it challenging to refrain from using them during activities such as eating, sleeping or playing.

With regard to the sociodemographic factors associated with greater adherence to pediatric recommendations, we identified, among others, higher education in one or both parents. Along the same lines, other studies have linked maternal higher education with increased supervision15 and lesser screen time,16,17 although we did not differentiate between mothers and fathers in the analysis of this factor. On the other hand, we found no association with household income, contrary to the findings of other studies16-18 in which higher incomes were associated with the possibility of offering children a broader range of leisure and extracurricular activities, thus reducing screen time.

Knowledge of the recommendations is associated with increased adherence to them. However, it is worth noting the high percentage of families that reported not having received information on the subject from a health care professional. Furthermore, we did not find an association between having been informed by a professional and improved adherence, which was consistent with previous studies.10,11 It would be difficult to determine the reasons for it, but this fact suggests that pediatricians may need to be more proactive in informing families about scientific recommendations and the possible risks associated with screen use.

With respect to parental perceptions of the impact of electronic devices, the majority considered that they were detrimental in every explored area, except for learning, for which the percentage who considered them beneficial slightly exceeded the percentage who considered them detrimental. A possible explanation for this discrepancy, as noted by Creszenci-Lanna and Grané,19 could be the existence of 100 000 applications categorized as “educational”, despite the lack of evidence supporting such a claim. Additionally, in the field of education, the need for alternative teaching methods during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 made the use of screens ubiquitous. Over the past year, calls to limit device use in classrooms have become more frequent, in agreement with the position held by the AEP.20

The data on the age at which children in the older age group received their first mobile phone are consistent with those reported by UNICEF.8 Although a high percentage of parents in this group stated that they had discussed the risks of the digital world with their children, only one-third had addressed the topic of sexual relationships, despite it being one of the potential dangers of unsupervised screen exposure.21

Among the main limitations of our study are potential memory and social desirability biases, as well as the absence of objective measures of screen time. Furthermore, as this is a single-center study, the results cannot be extrapolated to other settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Screen use in childhood is a present and growing reality. Although many families claim to be aware of screen use recommendations, adherence to them is suboptimal. The main sociodemographic factor associated with improved adherence was parental higher education.

The low proportion of families who reported having received information from health care professionals highlights the need to improve the dissemination of digital education, promoting the safe use of devices from the earliest stages of development and emphasizing the importance of modeling appropriate use.

Digital wellness should be a prominent area in health promotion, for which tools such as the Family Digital plan of the AEP are essential. Pediatricians have a key role to play in these efforts, relying on other professionals, such as pediatric nurses, but also cooperating with professionals and institutions in other fields, such as education.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

Author contributions: study concept, data collection, formal analysis, methodology, administration of the project, supervision, visualization, drafting and review of manuscript (ESM), data collection, formal analysis, methodology, drafting of manuscript (MCP), data collection, formal analysis (LDC), data collection, formal analysis, visualization (REGC), study concept, data collection, supervision, review of manuscript (MZA).

ABBREVIATIONS

AEP: Asociación Española de Pediatría · FDP: Family Digital Plan · OR: odds ratio · SD: standard deviation · 95 CI: 95% confidence interval.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Survey: /files/1117-6179-fichero/RPAP_2504_Material_suplementario_ENG.pdf

REFERENCES

- Reid Chassiakos YL, Radesky J, Christakis D, Moreno MA, Cross C; Council on communications and media. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162593. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2593

- Cartanyà Hueso À, Lidón Moyano C, González Marrón A, Martín Sánchez JC, Amigo F, Martínez Sánchez JM. Association between leisure screen time and emotional and behavioral problems in Spanish children. J Pediatr. 2022;241:188-195.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.09.031

- Gueron-Sela N, Gordon-Hacker A. Longitudinal links between media use and focused attention through toddlerhood: a cumulative risk approach. Front Psychol. 2020;11:569222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569222

- Zapata Lamana R, Ibarra Mora J, Henríquez Beltrán M, Sepúlveda Martín S, Martínez González L, Cigarroa I. Aumento de horas de pantalla se asocia con un bajo rendimiento escolar. Andes pediatr. 2021;92(4):565-575. https://doi.org/10.32641/andespediatr.v92i4.3317

- Salmerón Ruiz MA. Salud digital. Adolescere. 2023;XI(1):38-46.

- Lafontaine-Poissant F, Lang JJ, McKinnon B, Simard I, Roberts KC, Wong SL, et al. Social media use and sleep health among adolescents in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;44(7-8):338-46. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.7/8.05

- Valkenburg PM, Meier A, Beyens I. Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;44:58-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.017

- Impacto de la tecnología en la adolescencia. Relaciones, riesgos y oportunidades. 2021 [online] [accessed 21/10/2025]. Available at www.unicef.es/publicacion/impacto-de-la-tecnologia-en-la-adolescencia

- Hoyos Cillero I, Jago R. Sociodemographic and home environment predictors of screen viewing among Spanish school children. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(3):392-402. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdq087

- Pons M, Bordoy A, Alemany E, Huget O, Zagaglia A, Slyvka S, et al. Hábitos familiares relacionados con el uso excesivo de pantallas recreativas (televisión y videojuegos) en la infancia. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2021;95:e202101002.

- Asociación Española de Pediatría. Comité de Promoción de la Salud. Agencia Española de Protección de Datos. Plan digital familiar AEP. 2025 [online] [accessed 21/10/2025]. Available at https://plandigitalfamiliar.aeped.es/index.php

- Asociación Española de Pediatría. La AEP actualiza sus recomendaciones sobre el uso de pantallas en la infancia y adolescencia en base a la nueva evidencia científica. Diciembre 2024 [online] [accessed 21/10/2025]. Available at www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/20241205_ndp_aep_actualizacion_plan_digital_familiar_def.pdf

- McArthur BA, Volkova V, Tomopoulos S, Madigan S. Global prevalence of meeting screen time guidelines among children 5 years and younger: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):373-83. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6386

- Rideout V, Peebles A, Mann S, Robb M. B. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens, 2021. Common Sense. 2022 [online] [accessed 21/10/2025]. Available at www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2021

- De Pablo de las Heras M, Padilla Esteban ML, Pasamón García S, García Muro C, Toledo Gotor C, Boukichou Abdelkader N. Uso de redes sociales y dispositivos móviles en la población infantil de La Rioja. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:27-35. https://doi.org/10.60147/0573589c

- Jiménez-Morales M, Montaña M, Medina-Bravo P. Uso infantil de dispositivos móviles: Influencia del nivel socioeducativo materno. Comunicar. 2020;(64):21-8.

- Figueira M, Santos AC, Gregório MJ, Araújo J. Changes in screen time from 4 to 7 years of age, dietary patterns and obesity: Findings from the Generation XXI birth cohort. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;33(12):2508-2516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2023.07.032

- Gorrotxategi Gorrotxategi P, Delgado Pérez M, Etxeberría Hernando N, Legarda-Ereño Rivera E, Mateo Abad M; Grupo de investigación de Atención Primaria de Guipuzkoa. Uso de pantallas en menores de 6 años en Guipúzcoa. Características sociales y repercusiones sanitarias. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:145-53. https://doi.org/10.60147/f589a241

- Casablancas S, Pose MM, Raynaudo G. Evidencias acerca del uso, comprensión y aprendizaje con tecnología digital en la primera infancia. In: Creszenci-Lanna l, Grané M (Coord.) Infancia y pantallas. Evidencias actuales y métodos de análisis. Barcelona: Octaedro; 2021. p. 19-29. https://doi.org/10.36006/16283

- Asociación Española de Pediatría. Impacto de los dispositivos digitales en el sistema educativo. 2024 [online] [accessed 21/10/2025]. Available at https://plandigitalfamiliar.aeped.es/downloads/Impacto_dispositivos_digitales_en_el_sistema_educativo_CPS.pdf

- Paulus FW, Nouri F, Ohmann S, Möhler E, Popow C. The impact of Internet pornography on children and adolescents: A systematic review. Encephale. 2024;50(6):649-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2023.12.004