Vol. 27 - Num. 105

Original Papers

Vaccination coverage for non-funded vaccines in infants and its relationship with sociodemographic factors

Laura Segura Navasa, Tomás del Valle Budíb, M.ª Teresa Martínez Garcíac, Mar Agut Agut d

aPediatra. CS Illes Columbretes. Castellón de la Plana. Castellón. España

bMédico. Universidad Jaume I. Castellón de la Plana. Castellón. España.

cEnfermera pediátrica. CS Illes Columbretes. Castellón de la Plana. Castellón. España.

dPediatra. CS Grao de Castellón. Castellón. España.

Correspondence: L Segura. E-mail: lseguranavas@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Segura Navas L, del Valle Budí T, Martínez García MT, Agut Agut M. Vaccination coverage for non-funded vaccines in infants and its relationship with sociodemographic factors . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2025;27:37-47. https://doi.org/10.60147/1cbd0a83

Published in Internet: 06-02-2025 - Visits: 9687

Abstract

Introduction: in Spain, the common nationwide vaccination schedule establishes which vaccines are publicly funded in Spain. However, each regional health administration can fund alternative vaccines within its territory, thus exacerbating health inequalities, as families bear the cost of vaccines not funded in their community. The aim of our study was to assess the impact of sociodemographic factors on the administration of non-funded vaccines in infants aged 2 months at the Illes Columbretes and Grao primary care centers in Castellón (Valencian Community, Spain).

Materials and methods: we conducted a cross-sectional observational and descriptive study in a sample of 115 infants, collecting the data through a questionnaire administered to their parents or legal guardians. This was followed by bivariate, multivariate, and ROC analyses.

Results: the bivariate analysis showed that administration of the menACWY vaccine (covering meningococcal serogroups A, C, W and Y) increased with increasing maternal age, increasing educational attainment and active employment in either or both parents, Spanish nationality, acceptance of funded vaccines and decreasing household crowding index. Similarly, administration of the rotavirus vaccine increased with increasing educational attainment of either or both parents, maternal employment, Spanish nationality, acceptance of funded vaccines, previous vaccination of siblings with non-funded vaccines, increasing maternal age and decreasing household crowding index. The multivariate analysis linked vaccination with menACWY with greater maternal educational attainment and age, paternal employment and Spanish nationality, and linked rotavirus vaccination with greater maternal educational attainment, Spanish nationality lower household crowding index values.

Keywords

● Demographic factors ● Health inequities ● Meningococcal vaccines ● Rotavirus vaccinesINTRODUCTION

Vaccines are biological products that contain one or more antigens from a microorganism. They trigger an immune response that simulates the response to natural infection, thus reducing the transmission of pathogens and the severity of the disease they are designed to protect against.1

In Spain, the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System develops by consensus the vaccination schedule recommended for the entire country.2 However, regional health systems may publicly fund vaccines at the autonomous community level that are not included in the national schedule.3,4 This may contribute to social inequities, as families have to cover the cost of vaccines that are not publicly funded in their region. Our study focused on the two vaccines that are not publicly funded in the Valencian Community at the time it was conducted: the meningococcus ACWY (MenACWY) and rotavirus vaccines.3

In 2023, the Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría (Spanish Association of Pediatrics) (CAV-AEP) recommended the replacement of the monovalent meningococcus group C vaccine given at 12 months by the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine, as well as administration of MenACWY to infants aged more than 6 months with risk factors or whose guardians prefer the quadrivalent over the monovalent vaccine.2 At present, the proposed nationwide lifelong immunization schedule calls for its administration only at age 12 years,5 as implemented in the immunization schedule of the Valencian Community.6 However, several autonomous communities in Spain have replaced the monovalent meningococcal group C vaccine by the quadrivalent MenACWY vaccine.7

In addition, the CAV-AEP recommends administration of the rotavirus vaccine from 6 weeks post birth to all infants.2 However, in 2023, this vaccine was only funded for infants born preterm between 25 and 32 weeks’ gestation in the Valencian Community, while it was funded and administered to all infants in other autonomous communities.8,9 At present, the nationwide routine immunization schedule calls for its administration to all infants aged 2 months, with the objective that it be included in the official vaccination schedules of all autonomous communities in the country by the end of 2025.5 In the Valencian Community it is now funded in adherence with the recommended nationwide lifelong vaccination schedule,6 in contrast to other autonomous communities.7

In regard to socioeconomic factors, public health systems with funded vaccines achieve higher vaccination coverage rates compared to private health systems.10-13 Similarly, parental educational attainment is proportionally and positively associated with vaccination,13,14 especially maternal attainment.10,15 Conversely, other studies have found that economic difficulties related to parental unemployment and living in crowded conditions are associated with a lower probability of vaccination.11,16-18

When it comes to family-related factors, there is no clear evidence of a relationship between parental age and the administration of vaccines, as different studies have produced heterogeneous results.11,13,15-17 However, vaccination rates are lower in large households (officially defined as those with three or more children) and single-parent households.15,16 There is no evidence of an association between religious beliefs or a history of illness in infancy and the administration of vaccines.15 Spanish nationality is associated with an increased vaccination coverage for rotavirus.16

As regards the sources of information regarding vaccination, active promotion by health care professionals increases vaccination,12,16,19 especially in low-income families.15

Our hypothesis was that adverse sociodemographic factors would be associated with a decrease in the administration of both non-funded vaccines in infants aged 2 months. The primary objective was to assess the impact of socioeconomic conditions, family-related factors and sources of information about vaccines on the administration of the two vaccines that were not publicly funded in the Valencian Community at the time of the study: the menACWY and rotavirus vaccines.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study using data collected through the administration to parents or legal guardians of a questionnaire by the pediatricians and nurses of the Illes Columbretes and Grao primary care centers in Castellón, Spain.

Participants

The target population comprised 268 participants and included all children born in 2023 assigned to the aforementioned primary care centers. For the sample size calculation, we established an alfa level of 5% and estimated a proportion of non-funded vaccination of 85%, based on which we estimated that a minimum sample of 114 participants was necessary. Including infants brought in for the routine checkup at age 2 months by consecutive sampling, we obtained a final sample of 115 participants.

Ethical aspects

The study adhered to Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights, Law 41/2002 of November 14 regulating patient autonomy and the rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation, the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines. Since the patients were aged less than 12 years, it was the legal guardians that provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines of the Hospital General Universitario de Castellón (April 4, 2024).

Variables

- Exposure variable: the evaluation of sociodemographic factors included socioeconomic factors, family-related factors and the sources of information about vaccines.

We evaluated socioeconomic status based on the following variables: maternal educational attainment, paternal educational attainment, household crowding index (the number of household members minus 1 divided by the number of bedrooms), and maternal and paternal employment.

The family-related factors included in the analysis were: nationality, underlying disease in parents, underlying disease in the infant, number of siblings, separation in the family, single-parent family, religious beliefs, smoking in the household (consumption of at least one cigarette by at least one parent), refusal of funded vaccines, administration of nonfunded vaccines to siblings, maternal and paternal age.

The variables used to assess the sources of information regarding non-funded vaccination were: “I have received information on non-funded vaccines from the pediatrician, nurse or health care administration” and “I have received information regarding non-funded vaccines from other sources: television, Internet or radio.”

- Outcomes: administration of the first dose at age 2 months of the menACWY vaccine and the rotavirus vaccine, considered separately.

- Covariates: primary care center, pediatrician caseload, pediatrician age.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS version 29.0, setting an alpha level of 5%. We started by performing a descriptive analysis of the variable. This was followed by a bivariate analysis. Dichotomous and ordinal variables were compared by means of the chi-square test and the magnitude of the effect was assessed by the contingency coefficient and the Somers’ D, respectively. The quantitative variables were not normally distributed, so quantitative data were compared by means of the Mann-Whitney U test. Last of all, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis and ROC curve analysis, comparing the probability predicted by the model and the outcome data.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

In the sample of 115 patients, the data concerning parents were missing for 3 because their identity was not known. As regards the outcome variables, we found a vaccination coverage at age 2 months of 69% for the menACWY vaccine (95% CI: 60-77%) and 77% for the rotavirus vaccine (95% CI: 60-84%). Tables 1 and 2 summarize the data for the exposure variables and the covariates.

| Table 1. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Descriptive summary of quantitative exposure variables and covariates | ||

|---|---|---|

| M/Me | R/σ | |

| Socioeconomic variables | ||

| Household crowding index | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Family-related variables | ||

| Maternal age | 32.6 | 5.1 |

| Paternal age | 36.9 | 7 |

| Number of siblingsa | 1 | 0-4 |

| Covariates | ||

| Caseload | 760.4 | 22.1 |

| Age of pediatrician | 41.2 | 5.2 |

| Total (n = 115) | ||

|

M: mean; Me: median; R: range; σ: standard deviation. |

||

| Table 2. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Absolute frequency and percentage distribution of qualitative exposure variables and covariates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Socioeconomic variables | |||

| Maternal employment | Yes | 80 | 69.6% |

| No | 35 | 30.4% | |

| Paternal employment | Yes | 97 | 86.6% |

| No | 15 | 13.4% | |

| Maternal educational attainment | Primary, Compulsory secondary (ESO) or General Education Diploma | 23 | 20% |

| Non-compulsory secondary (Bachillerato) or vocational education | 43 | 37.4% | |

| University degree | 49 | 42.6% | |

| Paternal educational attainment | Primary, Compulsory secondary (ESO) or General Education Diploma | 24 | 21.4% |

| Non-compulsory secondary (Bachillerato) or vocational education | 46 | 41.1% | |

| University degree | 42 | 37.5% | |

| Family-related variables | |||

| Parental underlying disease | Yes | 19 | 16.5% |

| No | 96 | 83.5% | |

| Infant underlying disease | Yes | 5 | 4.3% |

| No | 110 | 95.7% | |

| Single-parent household | Yes | 4 | 3.5% |

| No | 111 | 96.5% | |

| Separation in family | Yes | 6 | 5.2% |

| No | 109 | 94.8% | |

| Nationality | Spanish | 79 | 68.7% |

| Not Spanish | 36 | 31.3% | |

| Religious beliefs | Yes | 43 | 37.4% |

| No | 72 | 62.6% | |

| Smoking in household | Yes | 37 | 32.2% |

| No | 78 | 67.8% | |

| Smoking in household | Yes | 10 | 8.7% |

| No | 105 | 91.3% | |

| Vaccination of sibling with non-funded vaccines | Yes | 39 | 33.9% |

| No | 76 | 66.1% | |

| Sources of information variables | |||

| Pediatrician | Yes | 79 | 68.7% |

| No | 36 | 31.3% | |

| Nurse | Yes | 106 | 92.2% |

| No | 9 | 7.8% | |

| Administrative staff | No | 115 | 100% |

| Other sources | Yes | 12 | 10.4% |

| No | 103 | 89.6% | |

|

Yes | 4 | 3.5% |

| No | 111 | 96.5% | |

|

Yes | 10 | 8.7% |

| No | 105 | 91.3% | |

|

No | 115 | 100% |

| Covariates | |||

| Primary Care Center | Illes Columbretes | 92 | 80% |

| Grao de Castellón | 23 | 20% | |

| Total (n = 115) | |||

Bivariate analysis

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of the bivariate analysis of the association between exposure variables and the administration of the MenACWY and rotavirus vaccines.

| Table 3. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Relationship between the administration of the menACWY or rotavirus vaccine and qualitative socioeconomic and family-related variables and different sources of information | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MenACWY | Rotavirus | |||||

| Socioeconomic variables | X2 | p-value | Ca/Db | X2 | p-value | Ca/Db |

| Maternal employment | 23.30 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 17.63 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Paternal employment | 10.80 | 0.001 | 0.3 | 0.99 | 0.319 | - |

| Maternal educational attainment | 29.60 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 32.56 | <0.001 | 0.36 |

| Paternal educational attainment | 14.02 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 19.04 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Family-related variables | ||||||

| Parental underlying disease | 1.11 | 0.292 | - | 0.75 | 0.387 | - |

| Infant underlying disease | 0.31 | 0.577 | - | 0.04 | 0.851 | - |

| Single-parent household | 0.67 | 0.412 | - | 0.01 | 0.942 | - |

| Separation in family | 3.68 | 0.055 | - | 0.34 | 0.559 | - |

| Nationality | 25.87 | <0.001 | 0.43 | 20.52 | <0.001 | 0.39 |

| Religious beliefs | 3.56 | 0.059 | - | 1.77 | 0.187 | - |

| Smoking in household | 1.09 | 0.298 | - | 1.19 | 0.276 | - |

| Refusal of funded vaccines | 24.03 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 19.48 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Vaccination of sibling with non-funded vaccines | 3.2 | 0.074 | - | 5.74 | 0.017 | 0.22 |

| Sources of information variables | ||||||

| Pediatrician | 0.56 | 0.453 | - | 0.05 | 0.830 | - |

| Nurse | 0.78 | 0.376 | - | 0.83 | 0.362 | - |

| Other | 0.67 | 0.413 | - | 0.72 | 0.395 | - |

| TV | 3.68 | 0.055 | - | 13.51 | <0.001 | 0.32 |

| Internet | 0.01 | 0.926 | - | 0.03 | 0.786 | - |

|

C: contingency coefficient; D: Somers’ D; X2: chi-square. |

||||||

| Table 4. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Relationship between the administration of the menACWY or rotavirus vaccine and quantitative socioeconomic and family-related variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MenACWY | Rotavirus | |||

| Socioeconomic variables | U | p-value | U | p-value |

| Household crowding index | 788.5 | <0.001 | 549.5 | <0.001 |

| Family-related variables | ||||

| Number of siblings | 1153.5 | 0.720 | 928 | 0.057 |

| Maternal age | 2045 | <0.001 | 1490 | 0.046 |

| Paternal age | 1470 | 0.361 | 1021.5 | 0.505 |

|

U: Mann-Whitney U. |

||||

Multivariate analysis

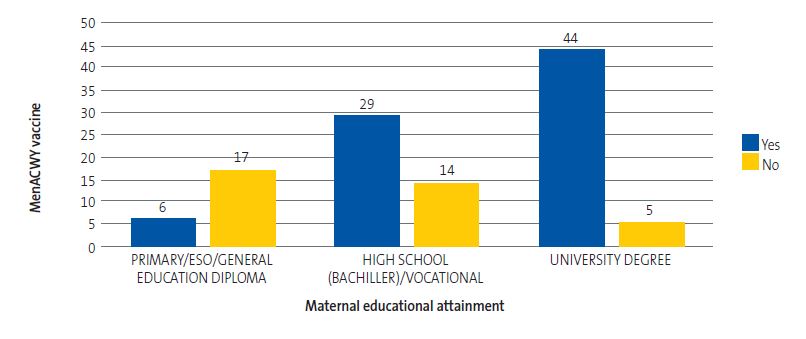

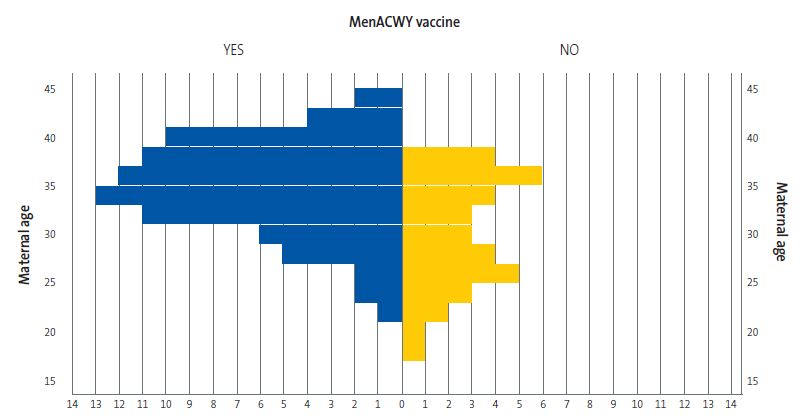

The model for the MenACWY vaccine suggests that maternal educational attainment (p = 0.003) (Figure 1), maternal age (p = 0.002) (Figure 2), paternal employment (p = 0.041) and Spanish nationality (p = 0.040) are positively correlated to the administration of the menACWY vaccine. The AUC in the ROC curve analysis was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.89-0.99).

| Figure 1. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Maternal educational attainment and frequency of vaccination with menACWY |

|---|

|

| Figure 2. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Maternal age and frequency of vaccination with menACWY |

|---|

|

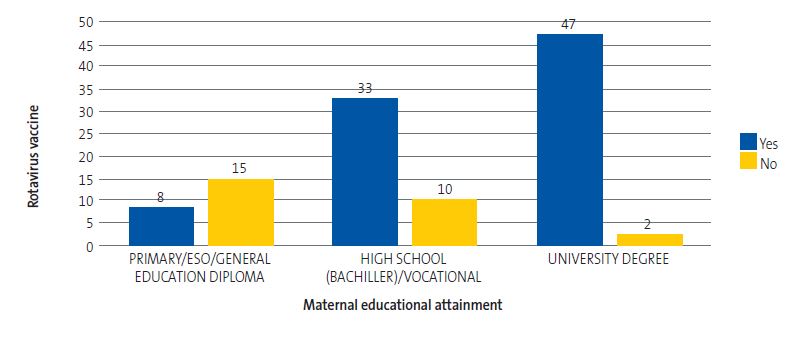

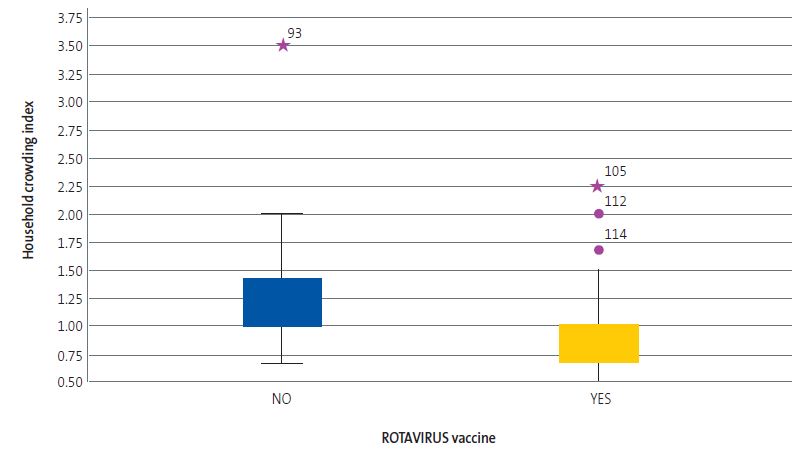

The model for the rotavirus vaccine suggests that maternal educational attainment (p = 0.012) (Figure 3), Spanish nationality (p = 0.032) and less crowded living conditions (p = 0.041) (Figure 4) are positively correlated to the administration of the rotavirus vaccine. The AUC in the ROC curve analysis was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86-0.99).

| Figure 3. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Maternal educational attainment and frequency of vaccination against rotavirus |

|---|

|

| Figure 4. Non-funded vaccines and socioeconomic variables. Household crowding index and administration of rotavirus vaccine |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

Our study identified multiple factors (socioeconomic, family-related and concerning sources of information) associated with the administration of the menACWY (quadrivalent vaccine against meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, and Y) and rotavirus vaccines at age 2 months.

We started by analyzing socioeconomic factors. Based on the previous literature, parental educational attainment is directly proportional to adherence to vaccination,13,14 especially in mothers.10,15 In our study, we found the same association with both vaccines. As reported by other authors, mothers with greater educational attainment accessed reliable sources of information, such as specialized journals, which allowed them to keep abreast of updated vaccination recommendations.10 We also believe that they are more proactive in pursuing preventive measures within a long-term holistic approach to health care.

The results of our study show that maternal employment is associated with a greater likelihood of administration of the menACWY and rotavirus vaccines. However, paternal employment was only associated with an increase in the administration of the menACWY vaccine. These findings were consistent with those of previous studies.15,20,21 One possible explanation is that actively employed parents are more likely to have the necessary income to afford payment for non-funded vaccines.

Lastly, greater crowding in the household was associated with a lower frequency of non-funded vaccine administration, which was consistent with the reviewed literature.16,18 Higher crowding index values are associated with adverse socioeconomic circumstances.22 In consequence, it is harder for these families to pay for out-of-pocket health care costs, and are less likely to do so for costs that are not associated with the treatment of acute conditions.22

Then, we analyzed family-related variables. We found an association between maternal age and vaccine administration for both of the vaccines (with vaccination coverage increasing with increasing maternal age), with no evidence of an association with paternal age. The findings reported in the reviewed literature varied widely.11,13,15-17 It is possible that older mothers have more information about vaccination and its benefits. On the other hand, younger mothers may not know basic facts about vaccination, as evinced in some studies.23

Contrary to the results of some previous studies,15,16 we found no evidence of an association of vaccination with single-parent family structure or separation in the family. It must be taken into account that, due to the low representation of these subgroups in the sample, the possibility of achieving significant results for this variable was drastically reduced.

The data obtained in our study showed that administration of the rotavirus vaccine was more likely if older siblings had received non-funded vaccines. We believe that these parents are more familiar with vaccination and its benefits. We should point out that we did not find the same association for the menACWY vaccine. Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is an infrequent condition compared to rotavirus gastroenteritis. We assume that, given the incidence of each of these diseases, parents are more aware of rotavirus and the advantages of vaccinating infants against it based on their personal experience or the experience of others in their social circle.

We found that Spanish nationality was associated with increased vaccination, in agreement with the reviewed literature.19,24 Spain has ideal conditions to achieve high vaccination rates,19 as vaccination is integrated in a public health care system whose administrators actively promote vaccination and in which the confidence and trust in vaccines of primary care providers has remained high through generations.19 However, vaccination rates are lower in inhabitants of non-Spanish origin. Based on the findings of previous studies, the main reasons for vaccination refusal are: barriers to health care access due to migrant status or ignorance of the involved administrative procedures,25 language barriers that hinder active pursuit of patients and promotion of vaccination by health care professionals, and cultural barriers that may influence decision-making in families regarding vaccination of their children, especially if the family cannot access reliable sources of information in Spain.25

The third aspect we investigated were the sources of information. Contrary to the findings of other authors,12,16,19 our study did not evince an association between vaccination and active promotion of vaccination by pediatricians and nurses. We believe the reason for this is that families that cannot afford the price of the vaccines will not purchase them, independently of the efforts of health care providers.

When it came to alternative sources of information, we found an increase in vaccination against rotavirus in parents who had been informed through television, which was consistent with previous evidence.16 The rotavirus vaccine was developed in 1998 and has been advertised on television worldwide. As a results, parents are more aware of it and consider whether or not to have their children vaccinated with it. In contrast, the menACWY has not received the same amount of public attention, as it was just included in the Spanish immunization schedule in 2019.

Limitations

Since patients were recruited by consecutive sampling without randomization, the sample may not have been representative of the target population. Due to the cross-sectional design, we were not able to determine whether the statistically significant associations persisted over time. Furthermore, the collection of data at the time of the routine checkup at age 2 months may have resulted in missing patients who received both vaccines in subsequent visits. Finally, the collection of data through a questionnaire carries a risk of recall bias.

CONCLUSION

The implementation of universal vaccination by public health systems is essential to reduce social inequalities and potentially preventable serious diseases. This study showed that the presence of unfavorable sociodemographic factors, especially socioeconomic factors and non-Spanish nationality, is associated with a lower frequency of administration of non-funded vaccines. The most recent immunization schedule proposed by the Interterritorial Council recommends inclusion of the rotavirus vaccine at age 2 months in the routine immunization schedule. In contrast, the menACWY vaccine is only recommended at age 12 years, although in some autonomous communities it is also administered at ages 4 and 12 months.5-7 This reinforces our opinion, as vaccines proven to be safe and effective should be funded by the public health system to reduce inequities in the population and ensure homogeneity in the immunization schedule across autonomous communities.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the development of the published manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

AUC: area under the curve · CAV-AEP: Advisory Committee on Vaccines of the Asociación Española de Pediatría · CI: confidence interval · IMD: invasive meningococcal disease · ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues in the Department of Pediatrics of the Illes Columbretes Primary Care Center, María Inmaculada Berlanga Andújar, Aránzazu Guerediaga Escribano, Vanesa Patrucco and Miguel Ángel Cabañero Pisa, and in the Department of Pediatrics of the Grao de Castellón Primary Care Center, Gloria Gil Grangel and María Inmaculada Ferré Franch.

REFERENCES

- Comité Asesor de Vacunas e Inmunizaciones (CAV-AEP). Generalidades de las inmunizaciones. Manual de inmunizaciones en línea de la AEP. In: CAV-AEP [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at http://vacunasaep.org/documentos/manual/cap-1

- Álvarez García FJ, Cilleruelo Ortega MJ, Álvarez Aldeán J, Garcés-Sánchez M, Garrote Llanos E, Iofrío de Arce A, et al. Calendario de inmunizaciones de la Asociación Española de Pediatría: recomendaciones 2023. An Pediatr (Barc). 2023;98(1):58.e1-58.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpedi.2022.10.002

- Vacunas y programa de vacunación. Calendarios de vacunación en las Comunidades. In: Ministerio de Sanidad - Áreas - Promoción de la salud y prevención [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/calendario/calendario/Calendario_CCAA.htm

- Pachón del Amo I, Limia Sánchez A, Jesús Pérez Martín J, Flora Martínez Pecino F, Lluch Rodrigo J, García Rojas A, et al. Criterios de evaluación para fundamentar modificaciones en el programa de vacunación en España. In: Comisión de Salud Pública del Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/comoTrabajamos/docs/Criterios_ProgramaVacunas.pdf

- Vacunas y programa de vacunación. Calendario de vacunación a lo largo de toda la vida 2025. In: Ministerio de Sanidad - Áreas - Promoción de la salud y prevención [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/calendario/home.htm

- Calendario de Vacunación 2025. In: Dirección General de Salud Pública. Generalitat Valenciana [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sp.san.gva.es/sscc/opciones4.jsp?CodPunto=3993&Opcion=VACCALINF&MenuSup=VACCALVACUNA&Seccion=VACCALINFCALV&Nivel=2

- Vacunas y Programa de vacunación. Calendario de vacunación a lo largo de toda la vida 2025. En: Ministerio de Sanidad - Áreas - Profesionales [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/calendario/

- Vacunación del rotavirus en los prematuros en España; 2022. In: CAV-AEP [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at https://vacunasaep.org/profesionales/noticias/vacunacion-del-rotavirus-en-los-prematuros-en-espana

- Limia Sánchez A, Navarro Alonso JA, Urbiztondo Perdices LC, Moreno Pérez D, Taboada Rodríguez JA, Arteagoitia Axpe JM, et al. Vacunación en prematuros [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/enfermedades/docs/Vacunacion_Prematuros.pdf

- Arat A, Burström B, Östberg V, Hjern A. Social inequities in vaccination coverage among infants and pre-school children in Europe and Australia - a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6597-4

- Khan N, Saggurti N. Socioeconomic inequality trends in childhood vaccination coverage in India: Findings from multiple rounds of National Family Health Survey. Vaccine. 2020;38(25):4088-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.023

- Gundogdu Z. Parental attitudes and perceptions towards vaccines. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7657. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7657

- Tauil MD, Sato AP, Waldman EA. Factors associated with incomplete or delayed vaccination across countries: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(24):2635-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.016

- Bertoncello C, Ferro A, Fonzo M, Zanovello S, Napoletano G, Russo F, et al. Socioeconomic Determinants in Vaccine Hesitancy and Vaccine Refusal in Italy. Vaccines. 2020;8(2):276. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8020276

- Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia E. Factors associated with suboptimal compliance to vaccinations in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(6):1719-41. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802085692

- Hara M, Koshida R, Araki K, Kondo M, Hirota Y. Determinants of self-paid rotavirus vaccination status in Kanazawa, Japan, including socioeconomic factors, parents’ perception, and children’s characteristics. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):712. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05424-6

- Bbaale E. Factors influencing childhood immunization in Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(1):118-29. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v31i1.14756

- Hungerford D, Vivancos R, Read JM, Iturriza-Gόmara M, French N, Cunliffe NA. Rotavirus vaccine impact and socioeconomic deprivation: an interrupted time-series analysis of gastrointestinal disease outcomes across primary and secondary care in the UK. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0989-z

- Larson H, de Figueiredo A, Karafllakis E, Rawal M. State of vaccine confidence in the European Union in 2018. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.374

- Feiring B, Laake I, Molden T, Cappelen I, Håberg SE, Magnus P, et al. Do parental education and income matter? A nationwide register-based study on HPV vaccine uptake in the school-based immunisation programme in Norway. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e006422. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006422

- Bocquier A, Ward JK, Raude J, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P, Ward J. Exp Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:1107-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2017.1381020

- World Health Organization, Shannon, Harry, Allen, Claire, Dávila, Daniella, Fletcher-Wood, Lizzie, et al. (2018). WHO Housing and health guidelines: web annex A: report of the systematic review on the effect of household crowding on health. World Health Organization. In: OMS [online] [accessed 30/01/2025]. Available at https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/275838

- Salmon DA, Smith PJ, Pan WKY, Navar AM, Omer SB, Halsey NA. Disparities in preschool immunization coverage associated with maternal age. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5(8):557-61. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.5.8.9009

- Salas YM, Guirado FJ, Marín MC, Romera AU, Martín JJ. IE-7644. Factores asociados a la vacunación frente a rotavirus en los lactantes no prematuros. 2022;23:4-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacun.2022.09.003

- Hernández Rincón EH, Lemus l, Quijano D, Rojas Alarcón DM, Segura T, Moreno A. Resistencia de la población hacia la vacunación en época de epidemias: a propósito de la COVID-19. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022;46. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2022.148