Vol. 26 - Num. 102

Original Papers

Evaluation of forensic medical care to victims of underage sexual violence in the province of Alicante (Spain)

Esperanza Navarro Escayolaa, Clara Vega Vegab, Rafael Bañón Gonzálezc, Mar Pastor Bravod

aSección de Laboratorio de Toxicología. Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses de Alicante. Alicante. España.

bSección de Policlínica y Especialidades. Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses de Alicante. Alicante. España.

cDirección General para el Servicio Público de Justicia. Ministerio de Justicia. Madrid. España.

dDirectora del Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses de Alicante. Alicante. España.

Correspondence: E Navarro. E-mail: enavarroescayola@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Navarro Escayola E, Vega Vega C, Bañón González R, Pastor Bravo M. Evaluation of forensic medical care to victims of underage sexual violence in the province of Alicante (Spain) . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2024;26:155-64. https://doi.org/10.60147/c27181a1

Published in Internet: 24-06-2024 - Visits: 13502

Abstract

Introduction: sexual abuse of minors is a complex social problem that requires a multidisciplinary approach.

Material and methods: retrospective descriptive study of 256 victims of sexual violence aged less than 18 years managed by the forensic medical team of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences of Alicante between 2016 to 2020. The sample was divided in two groups based on age: 0 to 12 years (104 cases; 40.6%) and 13 to 17 years (152 cases; 59.4%).

Results: In most cases, the victim was female (228 cases; 89.1%), a single perpetrator was reported (218 cases; 89%) and the perpetrator was known to the victim (185 cases; 74.6%). In the younger age group, the most frequent type of sexual violence was fondling (75 cases), while in the older age group it was vaginal penetration (57 cases). In 51 cases (19.9% of the total), repeated episodes of sexual violence occurred, mainly within the family. Most victims did not present with physical injuries (70.3% of the total). Almost half of the physical injuries (60 cases; 39.5%) and all the psychological sequelae (3 cases; 1.5%) occurred in the older age group. Chemical submission was suspected in 17 cases (6.7% of the total), mainly in the older age group (15 cases; 10.1%). The most frequently detected substance was alcohol, followed by cannabis and benzodiazepines.

Conclusions: our data show the important role of Institutes of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences as sources of information and providing resources that facilitate the detection of sexual violence and the development of prevention strategies.

Keywords

● Forensic examination ● Sexual violence in childrenINTRODUCTION

Child sexual abuse is the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared and cannot give consent, or that violate the laws or social taboos of society.1

There are two necessary criteria to meet the definition of child sexual abuse: the unequal status of the perpetrator and the victim (presence of an age, maturity or power differential) and the use of the minor for sexual purposes.2 In Spain, the legal age of sexual consent is set at 16 years.3,4

Child sexual abuse is a complex social problem of vast scope that causes profound unease in society. It is one of the least known social phenomena, as the subject is considered taboo.5 Therefore, it requires a multidisciplinary approach on the part of every involved institution (health care and educational services, court system, attorney general, law enforcement, the official institutes of legal medicine and forensic sciences and the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences (Instituto Nacional de Toxicología y Ciencias Forenses, INTCF).6

In 2023, a Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Forensic Evaluation Unit was created within the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (ILMFS) of Alicante, run by a multidisciplinary team of specialists in forensic medicine, psychology and social work. The physical space has been designed to fit the needs of forensic evaluations. Its purpose is to gather in one place all the agents involved in the institutional response to a child or adolescent who experience a traumatic criminal act. The aim of this unit is to establish and implement protocols to guarantee the protection of the minor, thus preventing secondary victimization, in adherence with the guidelines and recommendations issued by different international agencies.7,8

The aim of our study was to determine the incidence of sexual violence (SV) against children and adolescents to improve our knowledge and raise awareness of these situations, and to contribute to the measures required to prevent this type of violence.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective and descriptive study of minors aged less than 18 years victims of VS managed by the ILMFS of Alicante between 2016 and 2020.

The sources of data were the patient health records, the forensic report and the standardised data collection form included in the forensic medicine protocol for cases of crimes against sexual freedom of the ILMFS of Alicante9,10 and the protocol of the Forensic Medicine Council of the Ministry of Justice.11

We analysed data on sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, the circumstances of the event and the type of SV. We collected samples for biological, chemical and toxicological tests that were performed at the Barcelona branch of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences.

Cases of suspected chemical submission were reviewed by two researchers who applied the criteria for the definition of suspected drug-facilitated sexual assault proposed by Du Mont et al.12

The analysis of the resulting dataset was conducted with the statistical package SPSS version 15.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

Of the 702 cases of SV documented in the ILMFS of Alicante in the period under study, 256 (36.5%) occurred in minors under 18 years. The mean age was 11.8 years (range, 1-17 years; SD ± 4.809). The age mode was 15 years.

To improve the discriminant analysis of the variables, we divided the sample in 2 groups based on age: group A, ages 0 to 12 years (104 cases; 40.6%) and group B, ages 13-17 years (152 cases; 59.4%) (Table 1).

| Table 1. Profile of the victim, of the perpetrator and the place and time of sexual violence by age group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total | Group A (0-12 years) | Grupo B (13-17 years) | P |

| n (%) | 256 (100) | 104 (40.6) | 152 (59.4) | |

| Victim profile | ||||

| Sex | 256 (100) | 0.002 | ||

| Female | 85 (81.7) | 143 (94.1) | ||

| Male | 19 (18.3) | 9 (5.9) | ||

| Personal history | 254 (99.2) | 0.007 | ||

| Mental health disorder | 7 (6.7) | 30 (20) | ||

| Voluntary substance use | 252 (98.4) | 0.000 | ||

| Alcohol | 3 (2.9) | 62 (41.9) | ||

| Perpetrator profile | ||||

| Number of perpetrators | 245 (95.7) | 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 99 (98) | 119 (82.6) | ||

| 2 or more | 2 (2) | 25 (17.3) | ||

| Relationship to perpetrator | 248 (96.9) | 0.000 | ||

| Known to victim | 99 (97.1) | 86 (58.9) | ||

| Stranger | 1 (1) | 32 (21.9) | ||

| Recent acquaintance | 2 (2) | 28 (19.2) | ||

| Relative | 248 (96.9) | 0.000 | ||

| Father/stepfather | 36 (34.6) | 11 (7.2) | ||

| Grandfather | 9 (8.8) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Uncle | 7 (6.9) | 3 | ||

| Place and time | ||||

| Setting of abuse | 245 (95.7) | 0.000 | ||

| Home of perpetrator | 53 (53) | 54 (37.2) | ||

| Home of victim | 28 (28) | 16 (11) | ||

| Street | 6 (6) | 40 (27.6) | ||

| Club/bar/other leisure setting | 1 (1) | 15 (10.3) | ||

|

P: statistical significance (χ2 test) |

||||

Profile of victims (Table 1)

Most victims were female (228 cases; 89.1%), and only 28 ere male (10.9%). The proportion of male victims was greater in group A, with 19 cases (18.3%), compared to group B, with 9 cases (5.9%) (p = 0.002).

Alcohol was the substance that victims consumed voluntarily most frequently, chiefly in group B (62 cases; 41.9%), alone or combined with other substances (p = 0.000).

Profile of perpetrators (Table 1)

In most cases, the SV was perpetrated by a single attacker (218 cases; 89%) and was someone the victim knew (185 cases; 74,6%).

In approximately half of the cases in group B (60 cases; 41.1%) the perpetrator was a stranger or a recent acquaintance of the victim; while in nearly every case in group A (97.1%) the perpetrator was someone close to the victim (p = 0.000).

In more than half of group A, the perpetrator of SV was a relative: 62 cases (60.8%); compared to 16 cases in group B (11%) (p = 0.000).

When we analysed the frequency of SV based on the family relationship, the most frequent perpetrator was the father or stepfather (47 cases; 18.2%). By group, the proportion was greater in group A (34.6%), compared to group B (7.2%) (p = 0.000).

Context: time and place

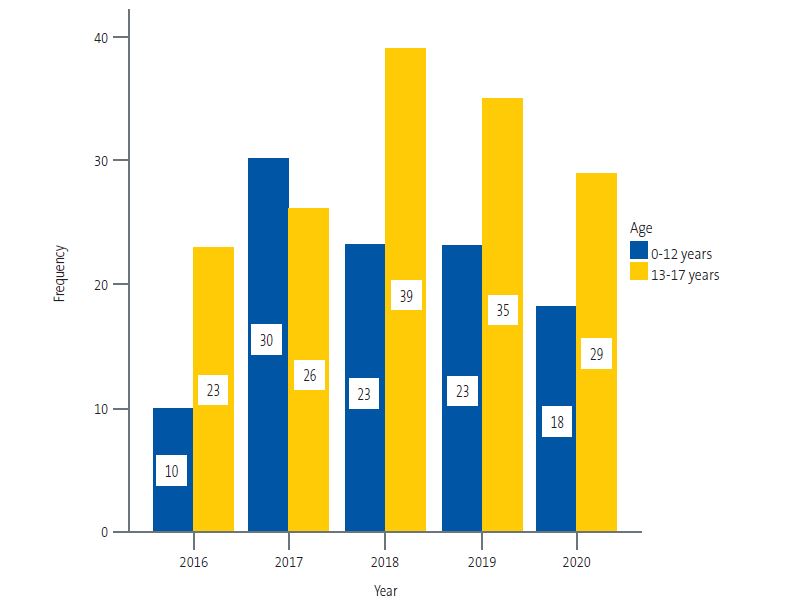

In the sample under study, the frequency of SV increased through the study period: 33 cases (12.9%) occurred in 2016, 56 cases (21.9%) in 2017, and the frequency peaked in 2018 with 62 cases (24.2%). In 2019 the frequency decreased slightly (58 cases; 22,7%) followed by a larger decrease in 2020 (47 cases; 18.4%), probably due to the circumstances that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Distribution of cases of sexual violence in underage victims through the years by age interval |

|---|

|

Sexual assaults occurred most frequently between the months of May and August (nearly half of cases, 42.8%) and on weekends, with 47 cases occurring on a Saturday (19%) and 46 on a Sunday (18.6%).

In 132 cases (53.4%) the approximate time of the assault was documented. In group B, assaults tended to take place at night and in the very early morning (93 cases; 81.6%); while in group A, SV predominantly took place in the morning or afternoon (11 cases; 61.1%) (p = 0.000).

In group A, the events took place, in order of decreasing frequency, in the home perpetrator, followed by the home of the victim. In group B, in the home of the perpetrator, followed by the street, the home of the victim and a club, bar or similar venue (p = 0.000) (Table 1).

Characteristics of sexual violence

In 51 cases (19.9%) the victims experienced recurrent episodes of SV. By age group, recurrent SV was much less frequent in group B (12 cases; 7.9%) (Table 2).

| Table 2. Characteristics of sexual violence by age group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total | Group A (0-12 years) | Group B (13-17 years) | P |

| n (%) | 256 (100) | 104 (40.6) | 152 (59.4) | |

| Type of sexual violence | 234 (91.4) | 0.000 | ||

| Fondling | 75 (73.5) | 22 (16.9) | ||

| Vaginal penetration | 7 (6.9) | 57 (43.8) | ||

| Anal penetration | 7 (6.9) | 7 (5.4) | ||

| Penetration of more than 1 orifice | 4 (3.9) | 26 (20) | ||

| Mixed (penetration, fondling, fellatio) | 8 (7.8) | 16 (12.3) | ||

| Number of SV episodes | 256 (100) | 0.000 | ||

| Single episode | 65 (62.5) | 140 (92.1) | ||

| Multiple episodes | 39 (37.5) | 12 (7.9) | ||

|

P: statistical significance (χ2 test); SV: sexual violence. |

||||

The time elapsed between the occurrence of the reported events and the evaluation and specimen collection was less than 24 hours in slightly more than half the sample (140 cases; 56.7%).

The most frequent type of SV was fondling (101 cases; 43.2%), followed by vaginal penetration (65 cases; 27.8%).

In group A, the predominant type of SV was fondling (75 cases), compared to vaginal penetration in group B (57 cases), followed by penetration of more than one orifice (26 cases), (p = 0.000) (Table 2).

Most victims did not have injuries (180 cases; 70.3%). Nearly half of the physical injuries (60 cases; 39.5%) and all psychological sequelae (3 cases; 1.5%) occurred in group B(p = 0,000).

In victims with physical injuries (76 cases; 29.7%), the most frequent location of the lesions was extragenital (54 cases; 21.1%), followed by anogenital lesions (39 cases; 15.2%). The detected psychological sequelae were anxiety, depression and mixed anxiety-depressive disorder.

Most physical injuries healed approximately within a week (65 cases; 95.7%) and none of the victims needed admission to hospital or developed physical sequelae. Three patients in group B (2%) developed psychological sequelae: worsening of depression in one case (0.7%) and development of depression in 2 cases (1.3%).

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were diagnosed in 2 patients: a boy aged 5 years with symptoms compatible with STD, with detection of antibodies against Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and Chlamydia trachomatis, and a girl aged 6 years that visited the hospital for assessment of the symptoms in whom testing detected Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Testing (Table 3)

Biological specimens were collected with swabs and/or from the clothing of the victim in 192 cases (75%). In 72 cases (50.7%) the results were positive for semen and/or prostate-specific antigen (PSA), most of them in group B (62 cases; 63.9%) (p = 0.000).

Blood, urine and hair samples were collected for chemical/toxicological analysis in 62 cases (24.2%). In the subset of 29 cases (11.3%) for which results were documented, there was suspicion of probable chemical submission in 17 cases (6.7% of total). The proportion of cases of suspected chemical submission was greater in group B, with 15 cases (10.1%). In group A, there were 2 suspected cases (1.9%), two siblings aged 10 and 11 years whose father gave them benzodiazepines to abuse them repeatedly (Table 3).

| Table 3. Biological specimen testing, suspected chemical submission and chemical/toxicology results by age group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total | Group A (0-12 years) | Group B (13-17 years) | P |

| n (%) | 256 (100) | 104 (40.6) | 152 (59.4) | |

| Biological results on record | 142 (55.5) | 0.000 | ||

| Positive | 10 (22.2) | 62 (63.9) | ||

| Negative | 35 (77.8) | 35 (36.1) | ||

| SCS | 256 (100) | 0.002 | ||

| Probable chemical submission | 2 (1.9) | 15 (10.1) | ||

| Toxicology results | 29 (11.3) | 0.036 | ||

| Alcohol | 0 | 6 (22.2) | ||

| Drugs | 0 | 2 (7.4) | ||

| Pharmaceuticals | 2 (100) | 3 (11.1) | ||

| Combination of substances | 0 | 5 (18.5) | ||

|

SCS: suspected chemical submission. |

||||

Alcohol was the substance identified most frequently (9 cases; 30.7%) alone or combined with recreational/illicit substances and/or pharmaceuticals. The identified pharmaceuticals, in order of decreasing frequency, were: benzodiazepines (4 cases), antidepressants (3 cases), antihistamines (2 cases) and antipsychotics (1 case). The recreational substance identified most frequently was cannabis (5 cases).

There are limitations to our study, as the sample only included cases in which a formal report was filed and the IMLCF of Alicante became involved. Thus, it did not include cases that were not reported, possibly those involving younger children, in whom it may be more complicated to identify red flags or other signs of SV, the “below the surface” child sexual abuse. It also excluded reported cases in which the legal authorities did not order a forensic evaluation and report.

DISCUSSION

The number of SV cases under 18 years recorded in the ILMFS of Alicante in the period under study was 256; more than half of the victims were adolescents aged 13 to 17 years. Mc Cauley et al.13 described adolescence as a period of high risk for SV. Nearly one third of sexual assault instances in the USA occur in this age group.

As described by other authors, most of the victims were female,13-16 with a greater proportion in the older age group17; the proportion of male victims was greater in the 0-12 years group (18.3%)18.

In our study, most of the sexual assaults were carried out by a single perpetrator that was known to the victim.19 In 20% of cases, there were recurrent SV episodes, similar to the findings of Csorba et al. (20%),20 chiefly in the family sphere.13,19 In more than half of the cases in victims under 13 years, the abuser was a relative.19 The greater vulnerability of minors demands heightened vigilance to detect these situations and, if there is the smallest hint or suspicion, closer monitoring of the minor.

In slightly more than half the cases, the medical evaluation was performed within 24 hours of the reported assault. This may be due to our study including only cases in which a report was filed and a forensic medicine specialist involved. Another factor at play was the high proportion of adolescents in our sample. As described in previous studies, adolescents tend to disclose the abuse faster. 21 At younger ages, discovery immediately following the sexual abuse episode is rare, and incidental discovery when some time has passed is more common.

Most victims presented without injuries.5 Injuries were more frequent in the older group.19 This finding was to be expected, as the most frequent type of SV in younger children was fondling, which rarely results in physical injury, which makes the assault go undetected. None of the physical injuries caused sequelae.

The small frequency of psychological sequelae in the sample was noteworthy, as they only developed in 3 cases, all in the 13-17 years group. Our findings were inconsistent with those of Mc Cauley et al.13, who found an association between being subject to sexual violence and an increased risk of post-traumatic stress, depression and substance use disorders in adolescents. The low frequency of psychological sequelae found in our sample may be related, as previously described by other authors,22 to the short time elapsed between the event and the examination, which tended to be short in the older age group in our study, and the low frequency of development of psychological sequelae in the short term. An adequate assessment would require a thorough clinical evaluation in each case to confirm causation in this type of disorder.23 Followup of the minor is also required to establish the full impact of SV. Although the scientific literature does not currently recognise a specific cognitive-behavioural syndrome resulting from the experience of child sexual abuse, we must highlight the repercussions of such abuse in the minor, which affect every area of life.5

Most cases that met the definition of probable chemical submission occurred in the 13-17 years age group. The most commonly detected substance was alcohol, followed in frequency by cannabis and benzodiazepines. In nearly half the cases, alcohol was the substance mainly consumed voluntarily by the victim before the assault. This was consistent with previous studies in which alcohol, alone or combined with other substances, was an important factor contributing to the victim’s vulnerability.24

CONCLUSIONS

Minors are more vulnerable and require more protection, so utmost vigilance is needed to detect this type of abuse as early as possible. The followup of minors who are victims of SV, both at the clinical and forensic level, is important to determine the full impact of the experienced SV.

Resources must be allocated to increase the visibility of this problem, planning education strategies so that health care professionals, teachers and families learn to identify warning signs to suspect SV, especially in children aged less than 13 years.

It is necessary for the interventions of each health care, law enforcement and legal professional involved in cases of reported child sexual abuse to be adequately coordinated. The creation in Alicante of the Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Forensic Evaluation Unit will help improve the care provided to minors after the experience of SV.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article. No funding was received to carry out this study.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the development of the published article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the chemistry department of the National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences (Barcelona branch) for their effort and professionality.

ABBREVIATIONS

IMLCF: Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses · SV: sexual violence.

REFERENCES

- Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention, 29-31, Document WHO/HSC/PVI. Ginebra, 1999. In: Iris VHO [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/65900

- Echuburúa E, Guerricaechevarría C. Abuso sexual en la infancia: víctimas y agresores, un enfoque clínico. 6th ed. Barcelona: Ariel; 2005.

- Orjuela López l, Rodríguez Bartolomé V. Violencia sexual contra los niños y las niñas. Abuso y explotación sexual infantil. Guía de material básico para la formación de profesionales. 2012. In: Save the Children [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/violencia_sexual_contra_losninosylasninas.pdf

- Ley Orgánica 1/2015, de 30 de marzo, por la que se modifica la LO 10/1995, de 23 de noviembre del Código Penal español de 2015. Título VIII, capítulo II bis, de los abusos y agresiones sexuales a menores de 16 años. In: BOE [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2015-3439

- Abuso sexual en la Infancia y la Adolescencia según los Afectados y su Evolución en España (2008-2019). 2020. In: ANAR [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.anar.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Estudio-ANAR-abuso-sexual-infancia-adolescencia-240221-1.pdf

- Actuación en la atención a menores víctimas en los Institutos de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. Consejo Médico-Forense. Ministerio de Justicia. Secretaría Técnica. Madrid, 2018. In: Ministerio de Justicia [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.mjusticia.gob.es/es/ElMinisterio/OrganismosMinisterio/Documents/ProtocoloViolenciaSexual.pdf

- Portal estadístico de criminalidad. Ministerio de Interior. In: Estadisticas de criminalidad [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at https://estadisticasdecriminalidad.ses.mir.es/publico/portalestadistico.html

- Convención sobre los Derechos del niño. Observación general n.º 14 (2013) sobre el derecho del niño a que su interés superior sea una consideración primordial (artículo 3, párrafo 1) ONU, 2013. In: UNHCR/ACNUR [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.refworld.org/es/ref/polilegal/crc/2013/es/95780

- Vega Vega C, Navarro Escayola E, Edo Gil JC. Protocolo de actuación médico forense en los delitos contra la libertad sexual. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2014;3:120-28. https://doi.org/1016/j.reml.2014.04.002

- Vega Vega C, Navarro Escayola E. Protocolo de Actuación Médico-Forense en los delitos contra la Libertad Sexual: Revisión y Actualización. Gac Int Cienc forense. 2021; 41:43-54.

- Protocolo de Actuación médico-forense ante la violencia sexual en los Institutos de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. Comité Científico-Técnico. Consejo Médico Forense, Secretaría General Técnica. Ministerio de Justicia. Madrid, 2021. In: Ministerio de Justicia [online] [accessed 22/08/2023] Available at www.mjusticia.gob.es/es/ElMinisterio/OrganismosMinisterio/Documents/ProtocoloViolenciaSexual.pdf

- Du Mont J, Macdonald S, Rotbard N, Asllani E, Bainbridge D, Cohen MM. Factors associated with suspected drug-facilitated sexual assault. CMAJ. 2009;180(5):513-9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080570

- McCauley Jl, Conoscenti M, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of Drug/Alcohol-facilitated and incapacitated sexual assault in a Nationally representative sample of adolescent girls. J Clin Chid Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(2):295-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698453

- Livano RM, Valdivia-Livano S, Mejía CR. Evaluaciones psicológicas forenses de abuso sexual en menores: proceso de revelación y cronicidad del evento en la serranía peruana. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2021;47:57-65.

- Finkelhor D, Hammer H, Sedlak AJ. Sexually assaulted children: national estimates and characteristics. US Government Printing Office. Washington, Juvenile Justice Bulletin-NCJ 214383, 2008. In: Office of Justice Program [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/214383.pdf

- Pereda N. ¿Uno de cada cinco? Victimización sexual infantil en España. In: Papeles del psicólogo. 2016;37(2):126-33 [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/pdf/2697.pdf

- Snyder H.N. Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: Victim, incident, and offender characteristics. US Department of Justice, Annapolis. Bureau of Justice statistics. In: Office of Justice Program [online] [accessed 22/08/2023]. Available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/sexual-assault-young-children-reported-law-enforcement-victim-incident-and

- Gewirtz-Meydan A, Finkelhor D. Sexual abuse and assault in a large national sample of children and adolescents. Child Maltreat. 2020;23(2):203-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559519873975

- Emmert C, Köhler U. Data about 154 children and adolescents reporting sexual assault. Arch Ginecol Obstet. 1998;261:61-70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004040050200

- Csorba R, Aranyosi J, Borsos A, Balla l, Major T, Póka R. Characteristics of female child sexual abuse in Hungary between 1986 and 2001: a longitudinal, prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:217-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.08.018

- Leyton C, Quezada D, Molina T. Perfil epidemiológico de adolescentes mujeres con antecedentes de agresión sexual consultantes en el área de salud mental de un centro de salud sexual y reproductiva. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 2013;78(1):26-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-75262013000100005

- Suárez Solá M, González Delgado F. Importancia de la exploración médico forense en las agresiones sexuales a menores. Cuad Med Forense. 2003;31:37-45.

- Kaur S, Kaur S, Rawat B. Medico-legal evidence collection in child sexual assault cases: a forensic significance. Egypt J Forensic Sci. 2021;11(41):1-6.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-021-00258-y.

- Gallo J, Padilla M. Abusos sexuales en niñas y adolescentes. Consideraciones médico legales. Clin Invest Gin Obst. 2006;33(6):222-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0210-573X(06)74121-1