Vol. 25 - Num. 100

Original Papers

Interdisciplinary intervention for the primary prevention of dental caries in children under 18 months

Rosa Juanola Mercadera, M.ª Lluïsa Ribas Casalsb, Anna Fàbrega Rierac, Laura Company Ardilad, M.ª Mercè Fina Rodejae, Silvia Pons Salvadore, Ruth Martí Lluchf, Jordi Blanchg

aEnfermera. ABS Vilafant. Gerona. España.

bEnfermera. ABS Bàscara. Gerona. España.

cPediatra. ABS Bàscara. Gerona. España.

dPediatra. ABS Figueres. Gerona. España.

eOdontóloga. ABS Figueres. Gerona. España.

fBióloga. Institut Universitari per a la Recerca en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol I Gurina (IDIAPJGol). Barcelona. España.

gMatemático. Institut Universitari per a la Recerca en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol I Gurina (IDIAPJGol). Barcelona. España.

Correspondence: R Juanola. E-mail: rjuanola.girona.ics@gencat.cat

Reference of this article: Juanola Mercader R, Ribas Casals ML, Fàbrega Riera A, Company Ardila L, Fina Rodeja MM, Pons Salvador S, et al. Interdisciplinary intervention for the primary prevention of dental caries in children under 18 months . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2023;25:367-76. https://doi.org/10.60147/5898493f

Published in Internet: 14-11-2023 - Visits: 12373

Abstract

Introduction: caries is the most common chronic disease in childhood. The presence of caries in the primary dentition is the main risk factor for developing caries in the permanent dentition. Most of the risk factors for caries are modifiable and can become elements for the prevention and control of the disease. With the goal of reducing the incidence of caries in children at age 18 months, we designed an interdisciplinary primary prevention intervention aimed at families with children who attended routine preventive visits within the PAPPS (“Protocol d’activitats preventives i de promoció de la salut a l’edat pediàtrica”) child health programme.

Methodology: non-randomized clinical trial carried out in two primary care centres in Catalonia between January 2019 and June 2022. In one of the centres, an educational intervention for the primary prevention of caries was designed and implemented to provide families with guidance and skills. In the other centre, patients received standard care. The incidence of caries was assessed and compared in both groups at age 18 months by means of a logistic regression model fitted with the R software.

Results: the incidence of caries at 18 months was higher in children in the control group (OR=6.0; 95% CI: 1.8-20.2), despite the fact that the caries risk assessment by means of the “Caries Management by Risk Assessment” (CAMBRA) protocol indicated a higher risk of caries in infants in the intervention group.

Conclusion: the interdisciplinary primary caries prevention intervention integrated into the child health prevention and promotion programme achieved a reduction in the incidence of caries in early childhood.

Keywords

● Dental caries ● Dental health education ● Fluoride ● Primary care ● Primary preventionINTRODUCTION

Caries (tooth decay) is the most frequent chronic childhood disease. Recent epidemiological studies conducted in Spanish preschoolers have found a prevalence of caries of 17.4% in children aged 3 years and up to 36.7% by age 5 years.1,2 In the catchment area of our primary care centre, the prevalence of caries observed in 2021 was 54% in children aged 6 years.

The aetiology of caries is multifactorial, although there are 3 essential factors that must coincide and persist through time: host characteristics (teeth and saliva), the presence of microorganisms and a diet rich in sugars.1 Other risk factors associated with the development of caries in early childhood are poor oral hygiene, reduced exposure to fluoride, early oral bacterial colonization, a family history of caries or low socioeconomic status.3 Most of these factors are modifiable, so they can be targeted in interventions aimed at preventing caries.1,3,4

Tooth decay in the primary dentition is the main risk factor for the development of cavities in the permanent dentition,5,6 and it is also associated with comorbidities such as periodontal infection, toothache, loss of teeth and even anorexia with an impact on body weight.5

Interdisciplinary educational interventions targeting caregivers of children aged 0-3 years and aimed at improving dietary and oral hygiene habits have been found effective and efficient in reducing the prevalence of caries.1,3,5,7,8 These interventions can be implemented at the primary care level, integrated in the routine visits scheduled as part of the official child health prevention and promotion programme (known as PAPPS), as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).2,5 Currently, the health education delivered in this health programme does not include some of the latest recommendations that have been found to be effective, such as the use of toothpaste with 1000-1450 parts per million (ppm) of fluoride from the eruption of the first tooth, the start of dental check-ups at 1 year of life or advice on preventing the transmission of microorganisms from the caregiver’s oral flora to the infant.1,2,4,7,9,10

The current oral health programme in Catalonia starts screening for tooth decay in the dental visit carried out during pregnancy, and does not contemplate any paediatric dental visits thereafter until preschool age (4-6 years), despite there being evidence that early initiation of dental screenings allows more effective treatment.

For all these reasons, the main objective of this study was to reduce the incidence of childhood caries at age 18 months through an interdisciplinary primary prevention intervention aimed at families with newborn infants who attended the routine visits of the PAPPS programme.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design: nonrandomised clinical trial carried out in the primary care centres (PCCs) of the health districts of Figueres (intervention group) and Roses (control group) between January 2019 and June 2022.

Inclusion criteria: newborn starting followup in the PAPPS programme in one of the 2 participating primary care centres.

Exclusion criteria:

- Diagnosis of diseases associated with abnormalities in dental eruption or morphology or tooth agenesis: Down syndrome, cleidocranial dysostosis, achondroplasia, ectodermal dysplasia, Gardner syndrome.

- Diagnosis of syndromes associated with enamel hypoplasia or genetic disorders of tooth structure, such as amelogenesis imperfecta or dentinogenesis imperfecta.

Sample size and sampling method: the sample size was calculated using the GRAMO software,11 which estimated that, for an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of less than 0.2 in two-tailed testing and for an expected loss to followup of 20%, 183 participants per group were needed to detect statistically significant differences in proportions for the incidence of caries, with the expected proportion estimated at 0.16 in the control group (based on objective data from the primary care centres) and 0.06 in the intervention group (approximated with the ARCSINUS transformation). Participants were recruited through consecutive sampling.

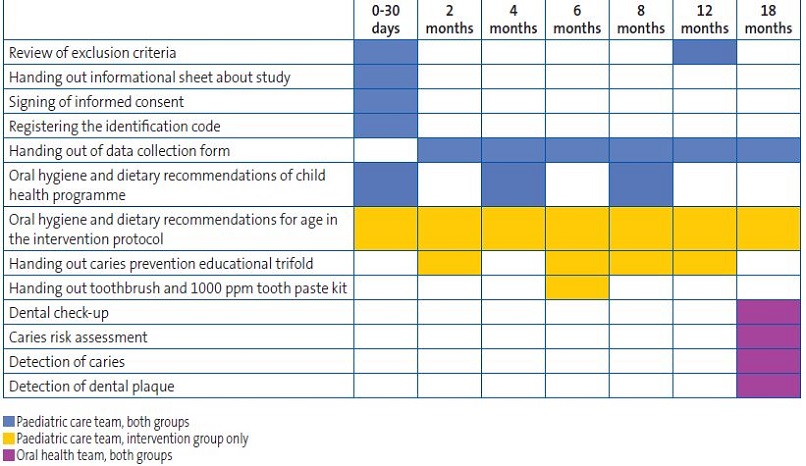

Intervention: the intervention group (Figueres PCC) underwent the intervention developed for the study, which was integrated in the routine PAPPS programme visits. The control group (Roses PCC) received standard care as established by the PAPPS programme guidelines (Table 1).

| Table 1. Activities carried out by the paediatric care team managing the intervention group (Figueres PCC), the paediatric care teams managing both groups and the oral health teams of the Figueres and Roses PCCs |

|---|

|

The interdisciplinary primary prevention intervention developed for the study was implemented in the following steps:

- The oral health team delivered a training session to the paediatrics care team focusing on up-to-date knowledge on caries: preventable risk factors for infant caries, appropriate oral hygiene techniques and tools, use of fluoride, “lift-the-lip” technique to detect white spots on teeth.

- The paediatric care team implemented the primary prevention interventions integrated in the PAPPS programme in the families that enrolled in the study.

- Education from the first visit, providing the family with the skills to identify and prevent cariogenic risk factors. The family received spoken information during the visit as well as an educational trifold leaflet developed by the oral health and paediatric care teams with recommendations on healthy eating, avoiding the oral transmission of microorganisms between caregivers and the infant and advice and skills for performing adequate dental hygiene based on the age of the child.

- Recommendations on the proper use of fluoride toothpaste (1000-1450 ppm fluoride) from the eruption of the first tooth, with a practical demonstration of the amount of toothpaste needed and the technique to achieve the cooperation of the child during oral hygiene. At the age 6 months visit, the family was provided with a free oral health kit comprising toothbrushes and a finger brush and one tube of fluoride toothpaste with 1000 ppm fluoride. Every participant in each group had a dental visit at age 18 months in which a dentist examined the child for caries and assessed the risk of early caries development (Table 1). The assessment of the risk of early caries was carried out according to the protocol for the management of children at high risk of caries at different ages and in different situations developed by the Sociedad Española de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (Spanish Society of Epidemiology and Public Health) in year 2013, which was based on the CAMBRA (caries management by risk assessment) approach. 12,13

Variables: the primary outcome of the study was the incidence of caries at age 18 months of age, recorded by the dental care providers. Caries was defined as follows: detection of one or more white spot (incipient) lesions or one or more cavities. The secondary outcome was the assessment of the risk of early caries performed by dentists based on the CAMBRA approach. The independent variables were: use of 1000-1450 ppm fluoride toothpaste from the eruption of the first tooth (yes/no); night-time feeding on demand without subsequent oral hygiene (no. of times/night), parents trying the food before feeding it to the baby (yes/no), parents blowing on the food before feeding it to the baby (yes/no), caregivers giving the child kisses on the mouth (yes/no), parents cleaning the baby's pacifier with their mouth (yes/no).

Covariables: we recorded the date of birth and sex of the infants participating in the study. We also collected information for other covariates in relation to the mother and father, such as: place of birth, educational attainment, employment status and whether the mother had attended the oral health screening visit during pregnancy (yes/no). We also collected information about the child regarding the feeding modality (breastfeeding/formula), intake of refined sugars (yes/no), sucking habits for sleep and oral hygiene habits and techniques in each routine follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis: we performed a descriptive analysis of the sample comparing both groups. Continuous quantitative data were summarised as mean and standard deviation if they were normally distributed and otherwise as percentiles, while qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. We used the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables and the Fisher exact test to compare categorical data.

To determine the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing the incidence of caries, we used the intention to treat approach. To analyse pre- and post-intervention differences within a group, we used tests for paired data. To estimate the impact of the intervention on the development of carries, we fitted a logistic regression model adjusted for those variables that had been statistically significant in the bivariate analysis. We applied the Firth correction to the logistic regression analysis, which is used to prevent bias in likelihood estimates when rare events are analysed.

In the comparison of the caries risk assessment with the CAMBRA approach, we calculated the proportion of patients in each group classified as “high risk” with the corresponding confidence interval (Wilson score interval method).

The level of significance was set at 0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out with the software R, version 4.2.1.

Ethical considerations: the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Institut Universitari d’Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol (file P18/204). Families were invited to participate during the initial PAPPS visit, scheduled at 1 month of life. We included all children who did not meet any exclusion criteria whose parents/guardians signed the informed consent form.

RESULTS

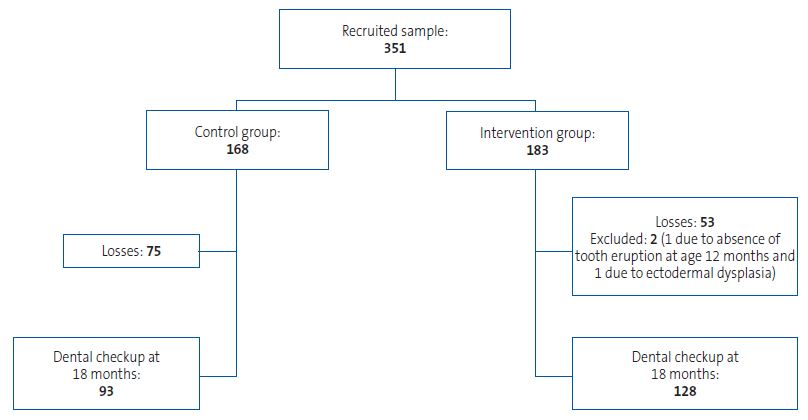

A total of 351 families met the inclusion criteria, of which 183 were included in the intervention group and 168 in the control group. The dental visit at age 18 months at the end of the study protocol was attended by 128 families in the intervention group (69.9%,) and 93 in the control group (55.4%). Figure 1 presents a flow chart of the sample through the study.

In the intervention group, 110 mothers (61.8%) had attended the dental screening visit during pregnancy, compared to 112 (72.3%) in the control group (p = 0.109).

Table 2 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of the participating families. In both groups, an intermediate educational attainment was most frequent in both mothers and fathers. We only found significant differences between the intervention and control groups in 2 variables, maternal employment status and parental place of birth. In the control group, there was a greater proportion of actively employed mothers and of parents born in Spain.

| Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants that completed the study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Intervention group | Control group | p value | |

| Sex of child | Male | 68 (53.1%) | 48 (52.7%) | 1.000 |

| Female | 60 (46.9%) | 43 (47.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | |||

| Paternal place of birth | Spain | 52 (40.9%) | 43 (47.3%) | 0.016 |

| Other European Countries | 5 (3.9%) | 10 (11.0%) | ||

| Africa | 40 (31.5%) | 28 (30.8%) | ||

| Latin America | 29 (22.8%) | 8 (8.8%) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 2 | ||

| Maternal place of birth | Spain | 53 (41.4%) | 40 (43.5%) | 0.067 |

| Other European Countries | 6 (4.7%) | 10 (10.9%) | ||

| Africa | 36 (28.1%) | 27 (29.3%) | ||

| Latin America | 32 (25.0%) | 12 (13.0%) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (2.6) 3 (3.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 | |||

| Paternal educational attainment | Primary or lower | 27 (21.3%) | 30 (32.6%) | 0.125 |

| Secondary | 75 (59.1%) | 50 (54.3%) | ||

| University or higher | 25 (19.7%) | 12 (13.0%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||

| Maternal educational attainment | Primary or lower | 21 (16.5%) | 27 (29.0%) | 0.084 |

| Secondary | 66 (52.0%) | 42 (45.2%) | ||

| University or higher | 40 (31.5%) | 24 (25.8%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 | |||

| Paternal employment status | Not employed | 8 (6.3%) | 7 (7.6%) | 0.789 |

| Employed | 119 (93.7%) | 85 (92.4%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | ||

| Maternal employment status | Not employed | 64 (50.0%) | 27 (29.0%) | 0.002 |

| Employed | 64 (50.0%) | 66 (71.0%) | ||

The cumulative incidence of caries in the intervention group was significantly lower compared to the control group. Three cases were detected in the intervention group (2.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.8-6.7%) and 13 in the control group (14.0%; 95% CI, 8.4-22.5%). The results of the logistic regression analysis showed that the risk of caries was 6 times greater in patients in the control group compared to the intervention group (odds ratio, 6.0; 95% CI, 1.8-20.2). None of the adjustment variables included in Table 2 were statistically significant.

The assessment of the risk of early caries performed at 18 months by the dental care team with CAMBRA approach found a higher proportion of patients at “high risk” of caries in the intervention group. In the intervention group, 69 participants were classified as “high risk” (55.2%; 95% CI, 46.5-63.6%) compared to 21 in the control group (31.3%; 95% CI, 21.5-43.2%).

We analysed whether there were differences in the incidence of caries associated with the collected data on child-related variables: feeding modality (breastfeeding/formula), refined sugar intake (yes/no) and sucking habits for sleep (pacifier/breast/bottle) (Table 3).

| Table 3. Incidence of caries in relation to the feeding modality, consumption of refined sugars and sucking habits for sleep. The incidence is presented with the corresponding 95% confidence interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |||||

| N | Incidence | N | Incidence | p value | ||

| Feeding modality | ||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding through 12 m | 0 | 3 | 11.5% (71.0-96.0) | 0.089 | ||

| Formula/mixed feeding by age 8 m | 2 | 2.1% (0.6-7.3) | 7 | 12.7% (6.3-24.0) | 0.012 | |

| Consumption of refined sugar in the first year of life | ||||||

| No ingesta | 1 | 2.1% (0.4-11.1) | 3 | 10.7% (3.7-27.2) | 0.144 | |

| Ingesta | 1 | 1.4% (0.2-7.4) | 5 | 11.9% (5.2-25.0) | 0.024 | |

| Sucking habits for sleep | ||||||

| Breast | 2 m | 0 | 6 | 14.3% (6.7-27.8) | 0.006 | |

| 4 m | 0 | 6 | 14.6% (6.9- 28.4) | 0.006 | ||

| 6 m | 1 | 1.8% (0.3 – 9.6) | 6 | 17.6% (8.3 -33.5) | 0.012 | |

| 8 m | 0 | 5 | 14.7% (6.4- 30.1) | 0.007 | ||

| 12 m | 0 | 5 | 17.2% (7.6-34.5%) | 0.008 | ||

| Bottle | 2 m | 1 | 5.3% (0.9- 24.6) | 4 | 21.1% (8.5- 43.3) | 0.340 |

| 4 m | 1 | 5.3% (0.9- 24.6) | 4 | 20.0% (8.1- 41.6) | 0.342 | |

| 6 m | 0 | 3 | 16.7% (5.8- 39.2) | 0.105 | ||

| 8 m | 2 | 7.4% (2.1 – 23.4 | 3 | 16.7% (5.8-39.2%) | 0.375 | |

| 12 m | 0 | 3 | 21.4% (7.6- 47.6) | 0.022 | ||

| Pacifier | 2 m | 1 | 3.6% (0.6-17.7) | 0 | 1.000 | |

| 4 m | 1 | 3.3% (0.6-16.7) | 0 | 1.000 | ||

| 6 m | 2 | 7.7% (2.1-24.1) | 1 | 9.1% (1.6-37.7) | 1.000 | |

| 8 m | 0 | 2 | 15.4% (4.3- 42.2) | 0,091 | ||

| 12 m | 1 | 3.7% (0.7- 18.3) | 11 | 11.8% (3.3-34.3) | 0.549 | |

In the subset of infants who were exclusively breastfed through age 12 months, the incidence of caries did not vary significantly between the intervention and control groups. On the other hand, in the subset of children fed formula or a combination of formula and breastmilk (mixed feeding) before age 8 months, the incidence of caries was significantly higher in the control group compared to the intervention group (p = 0.012).

As for the intake of refined sugar, there was no difference in the incidence of caries between the control and intervention groups in infants who had not consumed sugar in the first year of life. In contrast, in the subset of infants who consumed sugar during the first year of life, the incidence of caries was significantly higher in the control group compared to the intervention group (p = 0.024).

When it came to the sucking habits for sleep, among those infants who fell asleep at the breast, the incidence of caries was lower in the intervention group compared to the control group at every timepoint in the followup (2, 4, 6, 8 and 12 months). In the subset of babies that sucked on a bottle for sleep, we only found a significant difference in the incidence of caries between the intervention and control groups when this habit was present at age 12 months, but not before. There were no differences in relation to the use of a pacifier for sleep at any point of the followup.

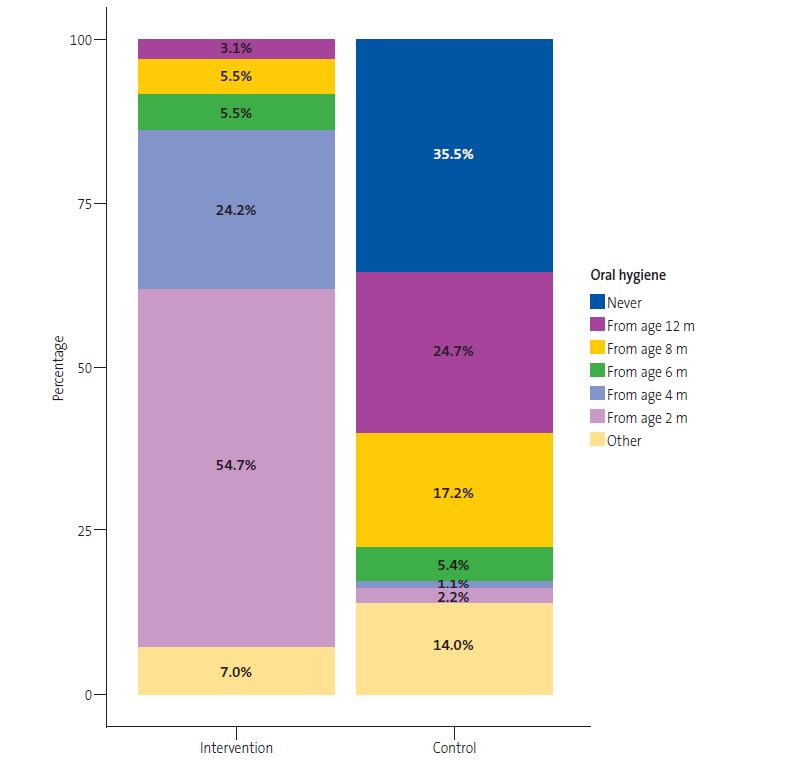

Oral hygiene habits differed between groups (p <0.01) (Figure 2). In the control group, 35.5% of children were not subject to any form of oral hygiene in the first year of life, while children in the intervention group underwent some form of oral hygiene.

We were unable to assess the association of other variables with the development of caries (parents trying the food or blowing on the food before feeding it to the baby, kissing baby on the mouth, cleaning the pacifier with the mouth), as parental habits had not changed after the educational intervention.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The educational preventive intervention against early caries integrated into the routine check-up visits of young children in a primary care centre was found to be effective, achieving a reduction in the incidence of caries at 18 months of age.

The intervention was also found to be effective in infants who were formula-fed or received mixed before age 8 months as well as infants who consumed sugary foods in the first year of life. The recommendations regarding oral hygiene and the restricting the intake of refined sugar provided in this intervention were supported by the current scientific evidence.1,2

We believe that the multidisciplinary approach of the intervention, involving paediatricians, nurses and dentists in primary care teams, was very important. The experience has been very positive, and it highlights the importance of collaborative care. In fact, multidisciplinary programmes for caries prevention have also been implemented and evaluated in Germany. In this case, the intervention was conducted in children aged 0 to 5 years and achieved a significant reduction in caries at ages 3 and 4 years. Programmes implemented in the past have been effective when prevention started before birth during visits with gynaecologists and midwives, and continued through the involvement of paediatric, social work and dental care teams.7,14. In our study, we did not find an association between the prenatal dental screening visit for pregnant women and the incidence of caries in young children, despite the fact that these visits include education about infant oral health and dental care, in adherence to the current protocol in our health care area.

The assessment of the risk of caries at age 18 months12 and the first visit to an oral health provider around age 1 year allows the initiation of primary prevention against caries in young children at high risk, in addition to early detection of lesions. The results of our study showed a higher risk of caries development in the intervention group compared to the control group, as children in the intervention group were at higher risk of caries, but the intervention still proved effective.

A randomised controlled trial carried out in an Irish dental practice with implementation of preventive interventions in children aged 2 and 3 years did not find statistically significant differences in the incidence of caries,15 although it did slow down caries progression in children who underwent the preventive intervention. This research group promoted dental hygiene with toothpaste with a 1450 ppm fluoride concentration, as recommended by the most recent paediatric oral health guidelines,6,8,10 and applied fluoride varnish for prevention in children at risk. The fact that the intervention targeted younger children could explain the observed differences in the development of caries. Based on our own findings and those of the Irish research group, it would be reasonable to conclude that preventive interventions implemented from birth—and maintained through age 3 years—can be beneficial in reducing both the incidence and the progression of caries. In terms of future research, it would be interesting to analyse the incidence of caries in children aged 3 and 4 years who had undergone caries risk assessment in the first year of life.

The main strength of the study is that it was the first to assess the implementation of an interdisciplinary primary prevention intervention against caries at a very early age, as no such studies have been conducted to date in children aged 18 months. The main limitations are intrinsic to the study design, as participants were not randomly allocated to groups, although the data collected at baseline did not evince significant differences between groups. Another limitation is that the study was conducted in 2020 and 2021, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a negative impact on the number of routine follow-up visits attended by participants due to the restricted access to primary care centres, which resulted in a smaller than expected sample size, although it still sufficed to detect significant differences in the incidence of caries between groups, which was the primary objective of the study.

The main conclusion of our study is that the integration of a multidisciplinary caries primary prevention intervention in the routine child health programme achieved a reduction in the incidence of caries at 18 months of age. In addition, early detection of infants at higher risk of caries allows earlier initiation preventive treatments.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

AUTHORSHIP

Authors' contributions: manuscript writing and revision (all), field work (RJM, MLLRC, AFR, LCA, MMFR, SPS).

ABBREVIATIONS

PAPPS: Protocol of Activities of Health Prevention and Promotion in the Paediatric age group · PCC: primary care centre · WHO: World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- Catalá Pizarro M, Cortés Lillo O. La caries dental: una enfermedad que se puede prevenir. An Pediatría Contin. 2014;12(3):147-51.

- Anil S, Anand PS. Early Childhood Caries: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Front Pediatr.2017;5:1-7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2017.00157

- Statement P. Maintaining and Improving the Oral Health of Young Children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1224-9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2984

- Phantumvanit P, Makino Y, Ogawa H, Rugg-Gunn A, Moynihan P, Petersen PE, et al. WHO Global Consultation on Public Health Intervention against Early Childhood Caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(3):280-287. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12362

- Hernández M. Diagnóstico, pronóstico y prevención de la caries de la primera infancia. In: Gaceta dental: Ciencia y clínica. 2017 [online] [accessed 07/11/2023]. Available at https://gacetadental.com/2017/12/diagnostico-pronostico-prevencion-la-caries-la-primera-infancia-15235/

- Winter J. Implementation and evaluation of an interdisciplinary preventive program to prevent early childhood caries. Clin Oral Investig. 2019 Jan;23(1):187-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2426-x

- Sedrak MM, Doss LM, Doss LM. Open Up and Let Us In: An Interprofessional Approach to Oral Health. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018 Feb;65(1):91-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2017.08.023

- Bernstein J, Gebel C, Vargas C, Geltman P, Walter A, Garcia R, et al. Listening to paediatric primary care nurses: a qualitative study of the potential for interprofessional oral health practice in six federally qualified health centres in Massachusetts and Maryland. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e014124. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014124

- Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H, Whall CW, Estrich CG, Zentz RR. Fluoride toothpaste efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):182-9. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):182-9. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.2013.37

- Protocol d’activitats preventives i de promoció de la salut a l’edat pediàtrica: infància amb salut. Scientia. 2008. In: Dipòsit d'Informació Digital del Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya [online] [accessed 07/11/2023]. Available at https://hdl.handle.net/11351/1197

- Calculadora [online] [accessed 07/11/2023]. Available at www.imim.cat/ofertadeserveis/software-public/granmo/

- Mateos Moreno MV. Llena Puy C, Rosario Garcillán Izquierdo M, Bratos Calvo E (reviewers). Protocolos para la actuación con niños con alto riesgo de caries en diferentes edades y situaciones. 2013 [online] [accessed 07/11/2023]. Available at https://sespo.es/wp-content/uploads/Protocolo-SESPO.-Actuacion-en-ninÌos-de-alto-riesgo-de-caries.pdf

- Maheswari SU, Raja J, Kumar A, Seelan RG. Caries management by risk assessment: A review on current strategies for caries prevention and management. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(2):S320-4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.163436

- Wagner Y, Heinrich-Weltzien R. Evaluation of a regional German interdisciplinary oral health programme for children from birth to 5 years of age. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21(1):225-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1781-8

- Tickle M, O’Neill C, Donaldson M, Birch S, Noble S, Killough S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of caries prevention in dental practice. J Dent Res. 2017;96(7):741-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034517702330