Vol. 25 - Num. 99

Original Papers

Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on social problems care. The perspective of paediatricians

Rafael Jiménez Alésa, M.ª Llanos de la Torre Quiralteb, Raquel Páez Gonzálezc, M.ª Luisa Poch Olivéd, Nisa Boukichou Abdelkadere

aPediatra. UCG Puente Genil. Puente Genil. Córdoba. España.

bPediatra. CS Labradores. Logroño. La Rioja. España.

cPediatra. CS Zona 5B. Albacete. España.

dServicio de Pediatría. Hospital San Pedro. Logroño. La Rioja. España.

eEstadística. Unidad de Ciencia del Dato. Innovación Sanitaria de Fundación Rioja Salud. Centro de Investigación Biomédica de La Rioja (CIBIR). Logroño. La Rioja. España.

Correspondence: R Jiménez. E-mail: rafael.jimenez.ales.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es

Reference of this article: Jiménez Alés R, de la Torre Quiralte MLL, Páez González R, Poch Olivé ML, Boukichou Abdelkader N. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on social problems care. The perspective of paediatricians . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2023;25:243-50. https://doi.org/10.60147/129e4760

Published in Internet: 28-09-2023 - Visits: 11465

Abstract

Objectives: to assess the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the management of social problems and the changes that took place in the communication with families and between professionals.

Methods: we collected data from 407 providers using a validated questionnaire. We used the binomial test to analyse the responses to the hypotheses, the Pearson correlation coefficient to see if the responses were influenced by age and the Mann-Whitney U test to assess whether the responses were influenced by sex, level of care, the setting of the centre, the professional category or the degree of specialisation.

Results: the confinement did not improve family relationships, but did increase the number of consultations from families for social problems and problems with new technology. There was an improvement in interprofessional communication. The improvement in the communication with families was not statistically significant in the overall sample, but it was significant in providers working in rural areas, primary care providers and older providers. There was also a significant impact on gender-based violence prevention and awareness programmes.

Conclusions: the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic had a significant impact on the management of social problems. From the point of view of providers, there was no improvement in family relationships. The measures taken to deal with the pandemic have improved communication between professionals.

Keywords

● COVID-19 ● Family relations ● Gender-based violence ● Interprofessional relations ● Social problems ● Surveys and questionnaires ● Technology addictionINTRODUCTION

The saturation of health care systems, the strict home confinement mandate, the halt in economic activity and the closure of schools caused by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic have had a direct impact on the wellbeing of children and adolescents, exacerbating the social problems that affect the paediatric population of Spain, including poverty, social exclusion, limited access to education and health care and domestic violence, which may detract from future opportunities. 1-3 The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on children, aggravating pre-existing social and economic inequalities and threatening the upholding of the rights of millions of children in Spain. It is possible that in the long term, all of this will have a more deleterious impact on children that the virus itself.4

The evidence to date shows that SARS-CoV-2 rarely causes severe disease in children.5 On the other hand, the pandemic has had a substantial psychological, economic and employment-related impact on most families, bringing on a social crisis of unprecedented scope.6-9 A crisis that has underscored the importance of the social determinants of health and the need for a biopsychosocial approach in paediatric care10, and the development of community-based care programmes.11

On the other hand, the health care system has been disturbed by the pandemic, prompting changes so that adequate care for presenting problems, not exclusively of a clinical nature, could continue to be delivered.7,8,12-14. In our region, data were not available on the potential advantages or drawbacks of these changes..

OBJECTIVES

Our aim was to analyse, from the perspective of paediatric providers, the impact of the pandemic on some relevant aspects related to social concerns in the framework of a broader project whose objective is to assess the attitudes, knowledge and difficulties in the management of social problems in paediatric patients.15

Starting with an analysis of the sociodemographic characteristics of responding providers and their care setting based on the postal code of the centre where they worked, 16 we formulated the following working hypotheses:

- Confinement improved family relationships (IFR).

- There was an increase in the number of consultations related to social problems overall (SPC).

- There was an increase in the number of consultations specifically related to the use of new technologies (INT).

- The technological improvements implemented on account of the pandemic have improved communication between providers and families (PFC).

- The technological improvements introduced in the care setting have improved communication between providers and/or care settings (IPC).

- The COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender violence prevention and awareness programmes (GVA).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a multicentre study approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Rioja (file CEImLAR P.I. 532), for which we developed and validated a questionnaire that was completed by 407 health care professionals through the Google Forms platform.12 The details regarding the distribution of the questionnaire can be consulted in the references.15 The validation process yielded 138 items distributed into 12 factors and 9 sociodemographic variables that described the knowledge and attitudes of health care professionals in the management of social problems in the context of paediatric care, the training received by these professionals, the tools available to them and the problems they encounter most frequently. Of these 12 factors, 1 concerned the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and this factor, in turn, comprised 6 items to assess the agreement with the proposed working hypotheses, rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The responses were analysed with the free software JASP and the statistical package R, version 4.2.2.

We analysed the responses in relation to the following variables: age of provider; level of care (primary care or hospital); speciality (paediatrician or family physician); characteristics of the catchment population (rural or urban setting, as defined by the National Institute of Statistics of Spain),18 based on the postal code of the area where the health care facility was located. We also compared physicians in training with medical doctors that had completed their speciality training. The distribution of respondents according to these variables can be found in Table 1.

| Table 1. Description of the sample (N = 407) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Distribución | n | Percentage | |

| Age |

Minimum Maximum Mean Median SD |

25 67 47 194 49 11 372 |

<49 years: 202 ≥49 years: 205

|

|

| Sex |

Male Female Declined to answer |

70 335 2 |

17.18% 82.32% 0.49% |

|

| Urban/rural |

Urban Rural Not documented |

353 51 3 |

86.73% 12.73% 0.74% |

|

| Primary care/Hospital |

Primary care Hospital Other |

275 82 50 |

67.57% 20.15% 12.28% |

|

| Paediatrician/FP |

Paediatrician FP |

394 13 |

96.81% 3.19% |

|

| Specialist/MIR |

Specialist MIR |

383 24 |

94.10% 5.90% |

|

|

FM: family physician; MIR: medical intern-resident. |

||||

RESULTS

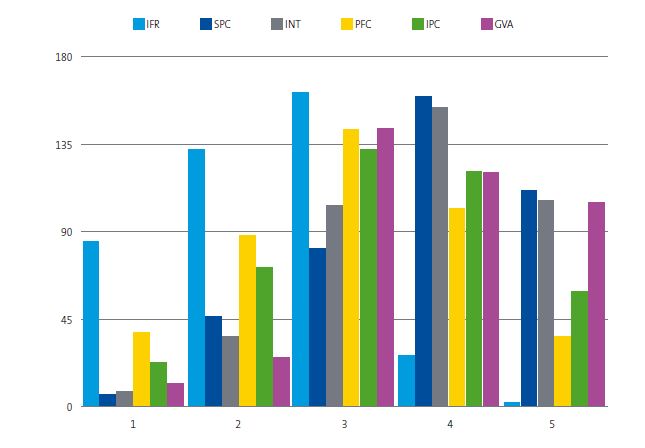

We performed hypothesis testing in the overall sample by analysing the 6 items that assessed the level of agreement or disagreement with the working hypotheses, comparing responses of 1-2 points (completely disagree or disagree) to responses of 4-5 points (agree or completely agree), and the null hypothesis was that the pandemic had not brought on any changes. The summary of the responses to the questionnaire can be found in Table 2 and Figure 1, and the results of the binomial test in Table 3.

| Table 2. Absolute frequency and percentage distribution of responses to the 6 items rated on a Likert scale | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFR | SPC | INT | PFC | IPC | GVA | |||||||

| Score | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 1 | 85 | 20.88 | 7 | 1.72 | 8 | 1.97 | 38 | 9.34 | 23 | 5.65 | 12 | 2.95 |

| 2 | 132 | 32.43 | 46 | 11.30 | 36 | 8.85 | 88 | 21.62 | 72 | 17.69 | 26 | 6.39 |

| 3 | 161 | 39.56 | 82 | 20.15 | 104 | 25.55 | 143 | 35.14 | 132 | 32.43 | 143 | 35.14 |

| 4 | 27 | 6.63 | 160 | 39.31 | 153 | 37.59 | 102 | 25.06 | 121 | 29.73 | 121 | 29.73 |

| 5 | 2 | 0.49 | 112 | 27.52 | 106 | 26.04 | 36 | 8.85 | 59 | 14.50 | 105 | 25.80 |

| Total | 407 | 100 | 407 | 100 | 407 | 100 | 407 | 100 | 407 | 100 | 407 | 100 |

|

GVA: the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender violence prevention and awareness programmes; IFR: confinement improved family relationships; INT: there was an increase in the number of consultations specifically related to the use of new technologies; IPC: the technological improvements introduced in the care setting have improved communication between providers and/or care settings; PFC: the technological improvements implemented on account of the pandemic have improved communication between providers and families; SPC: there was an increase in the number of consultations related to social problems overall. |

||||||||||||

| Figure 1. Distribution of the 407 responses to the 6 items rated on a Likert scale |

|---|

|

| Table 3. Binomial test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Nivel | Count | Total | Proportion | p |

| IFR | DISAGREED | 217 | 246 | 0.882 | < 0.001 |

| AGREED | 29 | 246 | 0.118 | 1 | |

| SPC | DISAGREED | 53 | 325 | 0.163 | 1 |

| AGREED | 272 | 325 | 0.837 | < 0.001 | |

| INT | DISAGREED | 44 | 303 | 0.145 | 1 |

| AGREED | 259 | 303 | 0.855 | < 0.001 | |

| PFC | DISAGREED | 126 | 264 | 0.477 | 0.788 |

| AGREED | 138 | 264 | 0.523 | 0.249 | |

| IPC | DISAGREED | 95 | 275 | 0.345 | 1 |

| AGREED | 180 | 275 | 0.655 | < 0.001 | |

| GVA | DISAGREED | 38 | 264 | 0.144 | 1 |

| AGREED | 226 | 264 | 0.856 | < 0.001 | |

|

NOTE. For all comparisons, the alternative hypothesis specifies that the proportion is greater than 0.5. GVA: the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender violence prevention and awareness programmes; IFR: confinement improved family relationships; INT: there was an increase in the number of consultations specifically related to the use of new technologies; IPC: the technological improvements introduced in the care setting have improved communication between providers and/or care settings; PFC: the technological improvements implemented on account of the pandemic have improved communication between providers and families; SPC: there was an increase in the number of consultations related to social problems overall. |

|||||

Most respondents disagreed with the statement that family relationships had improved during the confinement. Most agreed that there had been an increase in the number of visits related to social problems overall, especially with problems related to access to new technologies. Most also agreed that gender violence programmes had been affected during the pandemic. On the positive side, most respondents considered that there had been an improvement in interprofessional communication. As regards the improvement of the relationship of providers with families, although more respondents agreed with the statement, the difference in the comparison with those who disagreed was not statistically significant in the overall sample.

To finetune the analysis of the sample, we assessed whether the ratings on the Likert scale varied with age, with the Pearson correlation coefficient, or with the geographical setting of the facility (urban/rural), the type of professional (medical intern resident [MIR] or credentialed physician with completed training [specialist]), the level of care (primary care/hospital) or the speciality of the provider (paediatrician/family physician), with the Mann-Whitney U test. Table 4 presents the results of this analysis.

| Table 4. Analysis of the correlation between the working hypotheses and respondent-related variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotesis | Agea | Hospital/PCb | Rural/Urbanb | MIR/specialistb | Paed/FPb |

| P-value (z) | P-value (rB) | P-value (rB) | P-value (rB) | P-value (rB) | |

| IFR |

0.003** (+0.145) |

0.149 (+0.099) |

0.573 (+0.046) |

<0.001*** (+0.413) |

0.854 (-0.029) |

| SPC |

< 0.001*** (-0.237) |

0.503 (-0.047) |

0.576 (-0.046) |

<0.001*** (-0.404) |

0.510 (-0.102) |

| INT |

0.032* (-0.104) |

0.668 (+0.030) |

0.368 (-0.074) |

0.295 (-0.122) |

0.081 (-0.272) |

| PFC |

0.516 (+0.032) |

<0.001*** (+0.19) |

0.048* (+0.165) |

0.096 (+0.195) |

0.046* (+0.313) |

| IPC |

0.527 (+0.031) |

0.526 (+0.045) |

0.737 (+0.028) |

0.976 (-0.004) |

0.608 (+0.081) |

| GVA |

0.001** (-0.163) |

0.008** (-0.184) |

0.223 (-0.101) |

0.028* (-0.256) |

0.881 (+0.023) |

|

The effect size can range from−1 to +1, with 0.10 considered small, 0.30 medium and 0.50: large. A positive (+) correlation corresponds to a direct association (increasing); a negative (−) correlation corresponds to an inverse association (decreasing). aPearson linear correlation coefficient (effect size measured using Fisher’s z-score). bMann-Whitney U test (effect size measured using the biserial correlation coefficient [rB]). *p <0.05 **p <0.005 ***p <0.001 GVA: the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender violence prevention and awareness programmes; IFR: confinement improved family relationships; INT: there was an increase in the number of consultations specifically related to the use of new technologies; IPC: the technological improvements introduced in the care setting have improved communication between providers and/or care settings; PFC: the technological improvements implemented on account of the pandemic have improved communication between providers and families; SPC: there was an increase in the number of consultations related to social problems overall. |

|||||

As regards age, we found that older providers had a more favourable perception of the improvement in family relationships. In contrast, younger providers had a stronger perception of the increase in consultations related to social problems and problems related with new technologies, in addition to the deterioration of gender violence programmes. We did not find a significant association between age and the perceived improvement of the provider-family and interprofessional relationships.

As regards the care setting, we ought to highlight that primary care providers agreed more strongly that their communication with families had improved compared to hospital-based providers. This trend reversed when it came to the perceived impact on gender violence programmes. There were no significant differences in any other item based on the level of care.

When it came to the geographical setting (urban or rural), we found that providers in rural facilities had a more positive perception of the changes in the communication with families.

In the comparison of physicians in training and fully credentialed physicians, we found that medical residents agreed less with the statement that there had been improvement in family relationships, and more with the perceived increase in social problems and impact on gender violence programmes. There were no significant differences in the rest of the items.

As regards the speciality of the medical residents or credentialed physicians, we only found significant differences in the perception of family relationships, which were rated more favourably by paediatrics residents and paediatricians.

We did not find an association between the ratings and the caseload size in primary care physicians or the workload in hospital-based physicians. There were also no differences based on the sex of the respondent.

DISCUSSION

The initial impression upon obtaining the results would be that the confinement worsened family relationships. However, that statement was not presented in a way that allowed responding to it, but stated as a fact what had been reported in the literature.19,20 A significant disagreement with the statement does not allow concluding that the opposite was true, and further research would be required to assess this issue, with the advantage that the time that has elapsed would provide a better perspective to identify changes.

The pandemic may have acted as an amplifier of pre-existing protective and risk factors in families, 21,22 which would explain both the improvement described in the literature and the increase in consultations related to social problems that had been previously compensated by support from outside the household.

The analysis of the responses of physicians in training revealed substantial similarities to the responses of younger credentialed providers, although this was not the case when it came to the perception of problems related to new technologies, which suggests that the training period deserves specific analysis.

The stronger agreement of professionals in rural settings that the communication with families had improved could be attributed to the generally greater geographical dispersion and the related restrictions to health care access compared to urban areas. It is possible that many rural providers discovered the potential of telephonic followup with vulnerable families that tended to not visit their centres before the pandemic.

Although some of the subgroups in our sample were small, we were able to get statistically significant results, although it would have been better to obtain more responses representative of other points of view.

Chief among the limitations of the study is that, while the questionnaire was distributed widely, reaching nearly the entire population of professionals that it targeted, participation in the survey was voluntary, and this may have been an important source of cognitive bias, especially of availability heuristic, the bias resulting from relying on recent events to make an assessment.23

CONCLUSIONS

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has tested the stability of the health care system and of families, offering important lessons for the health care system, which has improved communication pathways between professionals and, in rural areas, between professionals and the population. At the same time, it has tested the cohesion of families, and may have acted as an amplifier, making problems that used to be hidden or compensated by external help more apparent, while increasing cohesion in families that were in a more favourable situation at the outset. Additional studies are required to investigate more thoroughly the risk and resilience factors in families that may explain these findings.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article. The study did not receive any form of funding.

AUTHORSHIP RESPONSIBILITY

Author contributions: design and field work (RJA, MLLTQ, RPG, MLPO), analysis of accumulated data (RJA, NBA), drafting of the manuscript, review and approval of the final version (RJA, MLLTQ, NBA, RPG, MLPO).

ABBREVIATIONS

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019 · MIR: medical intern-resident · SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

REFERENCES

- Barbet B, Costas E, Salinas P, Gómez C, Junquera C, Lafuente M. Impacto de la crisis por COVID-19 sobre los niños y niñas más vulnerables. Reimaginar la reconstrucción en clave de derechos de infancia. Madrid: UNICEF España; 2022. p. 3 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at unicef.es/sites/unicef.es/files/comunicacion/COVID_infanciavulnerable_unicef.pdf

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Equidad en Salud y COVID- 19. Análisis y propuestas para abordar la vulnerabilidad epidemiológica vinculada a las desigualdades sociales. Madrid; 2020 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/COVID19_Equidad_en_salud_y_COVID-19.pdf

- Esparza Olcina MJ, Perdikidi Olivieri l. El aislamiento de los recién nacidos en la pandemia de COVID-19 parece haber afectado a su desarrollo social. Evid Pediatr. 2023;19:4.

- Kyeremateng R, Oguda l, Asemota O, International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP) COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19 pandemic: health inequities in children and youth. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107(3):297-9.

- Carballal Mariño M, Balaguer Martínez JV, García Vera C, Morillo Gutiérrez B, Domínguez Aurrecoechea B, Jiménez Alés R, et al. Expresión Clínica de la covid-19 en pediatría de Atención Primaria: Estudio covidpap. An Pediatr (Barc) 2022;97:48-58.

- Atlas Nacional de España. La pandemia COVID-19 en España. Primera ola: de los primeros casos a finales de junio de 2020. In: Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Madrid: Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana; 2021 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.ign.es/web/ca/libros-digitales/monografia-covid

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) de España. Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida. Año 2020 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.ine.es/prensa/ecv_2020.pdf

- Aniversario Covid-19 ¿Que nos cuentan las familias? In: Save the Children [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.savethechildren.es/actualidad/informe-aniversario-covid-19

- Save the Children España. Crecer Saludable(mente). Un análisis sobre la salud mental y el suicidio en la adolescencia [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/2021-12/Informe_Crecer_saludablemente_DIC_2021.pdf

- Martínez González C. Ser pediatra en tiempos de pandemia. Form Act Pediatr Aten Prim. 2022;15(1):1-3.

- Núñez Jiménez C, Vázquez Fernández ME. La pediatría comunitaria. An Pediatr (Barc). 2021;94(2):116.e1.

- Ares Álvarez J, Albañil Ballesteros MR, Muñoz Hiraldo ME, García Gestoso ML, García Sánchez JA, Sánchez Pina C, et al. Documento técnico. Manejo pediátrico en atención primaria del COVID-19. 2020 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Manejo_pediatria_ap.pdf

- Coll Benejam T, Palacio Lapuente J, Añel Rodríguez R, Gens Barbera M, Jurado Balbuena JJ, Perelló Bratescu A. Organización de la Atención Primaria en tiempos de pandemia. Aten Primaria. 2021;53:102209.

- Albañil Ballesteros MR. Pediatría y COVID-19. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:125-8.

- Jiménez Alés R, Páez González R, de la Torre Quiralte ML, Poch Olivé ML, Boukichou Abdelkader N, Andrés Esteban EM. Creación y validación de un instrumento para Cuantificar actitudes, conocimientos y dificultades en el abordaje de los problemas sociales. An Pediatr (Barc).2023;98:418-26.

- Cofiño Fernández R. Tú código postal es más importante para tu salud que tu código genético (1). Aten Primaria. 2013;45(3):127-8.

- Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol (Chic). 1932; 22:5-55.

- Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana, 2021. Áreas Urbanas en España 2021. Madrid: Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana. pp. 21-39 [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at https://apps.fomento.gob.es/CVP/handlers/pdfhandler.ashx?idpub=BAW087

- Fischer Gaspard A, Zebdi R. Explorer familles l’expérience subjective du confinement Lié à l’épidémie de la covid-19 par les: Une analyse interprétative et phénoménologique (IPA) du discours de parents. Psychol Fr. 2022;67:337-56.

- Family Snapshot During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In: American Academy of Pediatrics [online] [accessed 22/04/2023]. Available at www.aap.org/en/patient-care/family-snapshot-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- Perrin EC, Leslie LK, Boat T. Parenting as primary prevention. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:637.

- Tardivo G, Suárez Vergne Á, Díaz Cano E. Cohesión familiar y COVID-19: Los Efectos de la pandemia sobre las relaciones familiares entre los jóvenes universitarios madrileños y sus Padres. RIPS: Revista De Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas 2021;20(1).

- Minué Lorenzo S, Fernández Aguilar C, Martín Martín J, Fernández Ajuria A. Uso de heurísticos y error diagnóstico en atención primaria: Revisión panorámica. Aten Primaria. 2020;52:159-75.