Vol. 25 - Num. 98

Original Papers

Association between meteorological factors and frequency and severity of asthma exacerbations attended in the pediatric emergency room

Cristina López Fernándeza, M.ª Teresa Leonardo Cabelloa

aServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Santander. España.

Correspondence: C López. E-mail: cristina_lopez_fdez@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: López Fernández C, Leonardo Cabello MT. Association between meteorological factors and frequency and severity of asthma exacerbations attended in the pediatric emergency room . Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2023;25:145-54.

Published in Internet: 19-05-2023 - Visits: 8959

Abstract

Object: the influence of climate on asthma exacerbations has already been demonstrated but the studies that analyze the association between different meteorological factors and acute asthma exacerbation in pediatric patients are limited. The aim of the present study is determining association between some meteorological conditions and asthma exacerbations in children in a third level referral Academic Hospital located in an oceanic-climate area.

Methods: we conducted a descriptive and retrospective study in 1 to 16 years old patients presenting with an asthma attack in the emergency department, during a 5-year period. Data about age, sex and the need for hospital admission were collected. Meteorological data (wind speed, rain, sunlight, temperature, humidity and barometric pressure) were obtained from the Environmental Research Center. The number of emergency department visits and percentage of hospital admissions were correlated to meteorological factors using logistic regression analysis.

Results: a total of 8534 asthma exacerbations were attended in the emergency department with a peak incidence in September. It was found that sunlight and rain were significantly and inversely correlated with emergency department visits and percentage of hospital admissions.

Conclusions: this study, conducted in an oceanic-climate area, confirms the previously described seasonal pattern for asthma exacerbations. We probe a statistically significant and inverse correlation between rain and sunlight and the number of emergency department visits for asthma and percentage of hospital admissions due to asthma attack.

Keywords

● Asthma exacerbation ● Epidemiology ● Rain ● Sunlight ● Temperature ● WeatherINTRODUCTION

Asthma is one of the most prevalent chronic respiratory diseases, affecting 1% to 18% of the world population.1 It is one of the main chronic childhood diseases, with a prevalence of 10% in Spain, similar to the overall prevalence in the European Union. It is more frequent in coastal areas and in boys aged 6 to 7 years.2

It is a heterogeneous disease characterised by the chronic inflammation of the airway, manifesting with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and airflow obstruction. The obstruction is variable and reversible, either spontaneously or with pharmacological treatment, at least partially.1,3

Asthma attacks, also known as exacerbations, involve worsening of symptoms relative to baseline in asthma patients to an extent that requires medical care and treatment. They are considered the most frequent medical emergency in paediatric care, with approximately 20% of patients requiring emergency care, and accounting for approximately 5% of emergency department visits. In addition, nearly 15% of patients that visit the emergency department require admission to an inpatient ward or the intensive care unit.4 As a result, asthma exacerbations place a considerable burden on the health care system and have a deleterious impact on the quality of life of affected children and their families.

Weather can affect the course of asthma directly, acting on the airway, and indirectly, by affecting the levels of allergens and pollutant in the air.5 Few studies have analysed the association between meteorological factors and asthma exacerbations managed in the paediatric emergency care setting, and their findings have been contradictory.

The aim of our study was to assess the impact of various meteorological variables on the paediatric asthma exacerbations managed in the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital located in a region with oceanic climate.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was conducted in Cantabria, an autonomous community in northern Spain with oceanic climate. The latter is characterised by abundant rains distributed regularly throughout the year and mild temperatures within a narrow range, also in summer and winter.

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study of patients aged 1 to 16 years who presented with asthma exacerbations to the paediatric emergency department of the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander, Spain) over a period of 5 years. This hospital is a tertiary care facility that is the referral hospital for the entire paediatric population of Cantabria (approximately 72 000 inhabitants under 16 years), and has a paediatric emergency department that manages 39 800 emergency visits a year. The diagnostic and therapeutic management of asthma exacerbations conforms to a specific protocol approved for the hospital, which is based on national asthma management guidelines and the protocol developed by the Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (SEIP, Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine).

To identify eligible cases, we searched the electronic health record database and its diagnostic codes. We included patients aged 1 to 16 years managed in the paediatric emergency department between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2018. We searched for the terms “asthma exacerbation” and “bronchospasm”. We excluded infants aged less than 1 year to avoid potential confusion with viral infections, such as bronchiolitis. We collected data on the date of birth, management at the emergency department, sex and need of hospital admission.

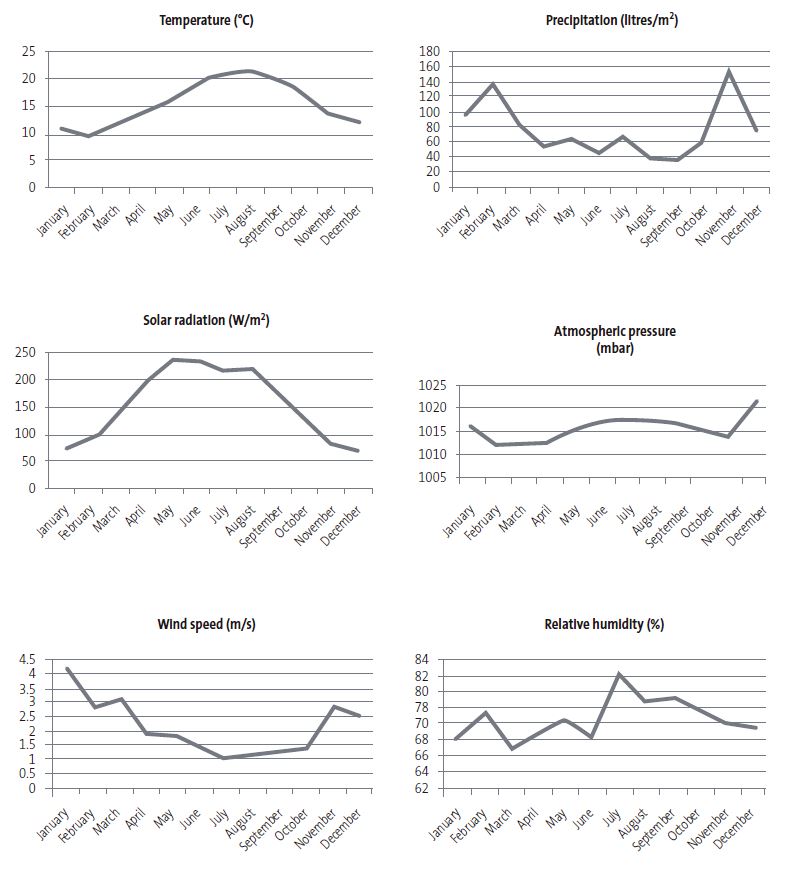

We obtained meteorological data from the Centro de Investigación del Medio Ambiente (CIMA, Centre of Environmental Research) for a weather station located 25 km from the hospital. We collected the monthly mean values for: wind speed (m/s), temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), atmospheric pressure (mbar), solar radiation (W/m2) and precipitation (litres/m2).

We summarised normally distributed variables as mean and standard deviation and nonparametric variables as median and interquartile range. We expressed qualitative or categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. In the comparative analysis of quantitative data, we used the t test for independent samples or, in the case of variables without a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test. To compare qualitative variables, we used the χ2 test. We considered p values <0.05 statistically significant. The association between the different meteorological factors and the number of asthma exacerbation episodes managed in the emergency department and their severity (assessed through the proportion that required hospital admission) was assessed by means of logistic regression. We repeated the same analysis by age group, dividing the sample into 4 groups (1 to 2 years, 3 to 6 years, 7 to 10 years and 11 to 16 years). The statistical analysis was conducted with the software IBM SPSS statistics for Macintosh, version 20.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

RESULTS

During the study period, there were 8534 emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation or bronchospasm that accounted for 4.2% of emergency department visits in that period. This corresponded to a mean of 142.23 visits per month for this presenting problem (standard deviation [SD] 64). The median age of the sample was 4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2-7) and 61.8% of the patients were male.

Hospital admission was required in 11.8% of cases (1004 patients), and admissions related to asthma exacerbations amounted to 8.7% of total paediatric admissions from the emergency department in the study period. Table 1 presents the annual distribution of emergency department visits and admissions due to asthma exacerbation.

| Table 1. Annual distribution of emergency department visits and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total visits | Visits due to asthma | Percentage of visits due to asthma | Total admissions | Admissions due to asthma | Percentage of admissions due to asthma |

| 2014 | 41 589 | 1748 | 4.2% | 2218 | 207 | 9.3% |

| 2015 | 39 437 | 2054 | 5.2% | 2712 | 254 | 9.3% |

| 2016 | 39 171 | 1928 | 4.9% | 2389 | 224 | 9.3% |

| 2017 | 39 942 | 1343 | 3.3% | 2164 | 143 | 6.6% |

| 2018 | 38 974 | 1461 | 3.7% | 2103 | 190 | 9.0% |

| Total | 199 113 | 8534 | 4.2% | 11 586 | 1018 | 8.7% |

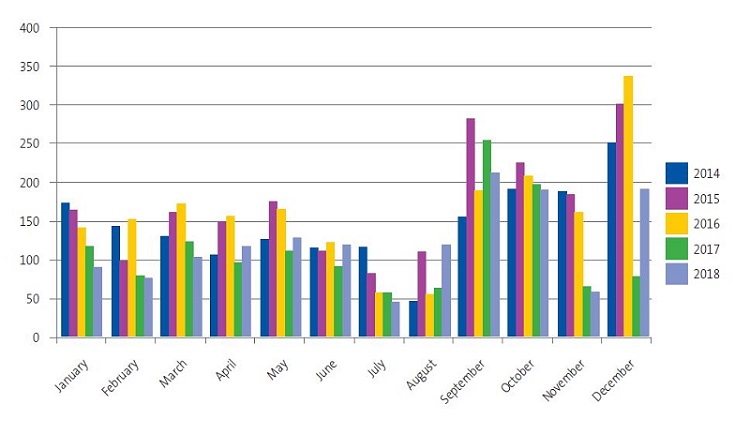

Figure 1 presents the monthly distribution of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation. There was a gradual increase in the first months of the year, followed by a decrease in the summer months, and an incidence peak starting in September. A mean of 219.8 patients were managed in the month of September, accounting for 7.8% of total de emergency department visits.

Figure 2 shows the monthly trends in the meteorological factors under study.

The logistic regression analysis performed to assess the impact of meteorological factors on the number of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation found a statistically significant inverse correlation with solar radiation and precipitation. The remaining meteorological factors under study did not seem to have a significant impact on the number of emergency visits made by our patients (Table 2).

| Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of the association between emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation and meteorological factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | p | |

| (Constant) | -0.579 | 0.565 | |

| Wind speed | -0.196 | -1.233 | 0.223 |

| Temperature | -0.086 | -0.471 | 0.639 |

| Relative humidity | 0.010 | 0.069 | 0.945 |

| Atmospheric pressure | 0.096 | 0.733 | 0.467 |

| Solar radiation | -0.587 | -3.329 | 0.002 |

| Precipitation | -0.458 | -3.057 | 0.004 |

When it came to the proportion of hospital admission as an indicator of the severity of the managed asthma exacerbations, we found a strong association with the number of emergency department visits (p = 0.000). Eliminating this factor from the analysis, we found a statistically significant inverse association between the proportion of hospital admission and both solar radiation and precipitation. For the rest of the meteorological factors under study, we also found no association with the percentage of patients admitted to hospital (Table 3).

| Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of the association between the number of hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbation and meteorological factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 0.337 | 0.737 | |

| Wind speed | -0.159 | -0.898 | 0.373 |

| Temperature | -0.060 | -0.292 | 0.771 |

| Relative humidity | 0.090 | 0.580 | 0.564 |

| Atmospheric pressure | -0.037 | -0.256 | 0.799 |

| Solar radiation | -0.395 | -2.004 | 0.050 |

| Precipitation | -0.359 | -2.142 | 0.037 |

In the subanalysis by age group we once again found a statistically significant inverse association between the number of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation and both precipitation and solar radiation, except in the oldest age group (11-16 years), in which we only found an inverse association with precipitation. We did not find an association with any other meteorological factor in any of the age groups (Table 4).

| Table 4. Logistic regression analysis by age group of the association between emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation and meteorological factors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind speed | Temperature | Relative humidity | Atmospheric pressure | Solar radiation | Precipitation | |

| 1-2 years (n = 2996) | ||||||

| Beta | -0.102 | -0.163 | -0.070 | 0.178 | -0.605 | -0.419 |

| t | -0.698 | -0.965 | -0.542 | 1.480 | -3.730 | -3.038 |

| p | 0.488 | 0.339 | 0.590 | 0.145 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| 3-6 years (n = 3256) | ||||||

| Beta | -0.216 | -0.036 | 0.064 | 0.003 | -0.534 | -0.423 |

| t | -1.283 | -0.187 | 0.434 | 0.019 | -2.855 | -2.655 |

| p | 0.205 | 0.852 | 0.666 | 0.985 | 0.006 | 0.010 |

| 7-10 years (n = 1647) | ||||||

| Beta | -0.273 | -0.101 | 0.068 | 0.034 | -0.383 | -0.459 |

| t | -1.613 | -0.517 | 0.459 | 0.244 | -2.035 | -2.867 |

| p | 0.113 | 0.607 | 0.648 | 0.808 | 0.047 | 0.006 |

| 11-16 years (n = 635) | ||||||

| Beta | -0.163 | 0.073 | -0.039 | 0.087 | -0.420 | -0.139 |

| t | -0.908 | 0.356 | -0.248 | 0.592 | -2.117 | -0.825 |

| p | 0.368 | 0.723 | 0.805 | 0.556 | 0.039 | 0.413 |

DISCUSSION

The studies in the literature analysing the role of different meteorological factors in asthma exacerbations in the paediatric population have yielded heterogeneous and, in some instances, contradictory results, with differences in the meteorological variables found to be associated with exacerbations or the direction or strength of the association.6-17

Previous studies have found an association of asthma exacerbations with environmental temperature,6-14 relative humidity,6,7,9-11,13-15 precipitation,6-8,11,16,17 wind velocity7,10,11,13-15 and atmospheric pressure12-14.

In our study, of all the meteorological variables under consideration, only precipitation and solar radiation exhibited a statistically significant association with exacerbation, which was negative.

In our sample, the results show that an increase in precipitation is associated with a decreased number of emergency department visits and hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbation. The previous evidence on the association between precipitation and asthma exacerbations in children is scarce and contradictory. However, our findings were similar to those reported by Xirasagar et al., whose study found an inverse association between precipitation and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbation in children aged less than 2 years.16 Similarly, Witonsky et al. published a retrospective study that found an inverse association between precipitation and the frequency of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation.6 In opposition, other studies found a direct association between precipitation and asthma exacerbations.7,17

The negative association between precipitation and emergency department visits due to asthma found in our study could be explained taking into consideration factors related to pollution. A study conducted in Taiwan found a strong association between certain meteorological variables and air pollution that could contribute to triggering asthma exacerbations.8 The authors simultaneously analysed the frequency of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation, several meteorological variables and the concentration of the major air pollutants. They found lower concentrations of most of the pollutants included in the analysis (sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide de, particular matter with a diameter of less than 10 µm and of less than 2.5 µm) in association with greater precipitation, which suggests that these pollutants are partly removed from the air by rainfall. The authors also found a reduction in the number of emergency department visits on rainy days, which was greater in children compared to adults.8

This hypothesis could explain our results, although we were unable to demonstrate it, as we did not have records of the concentration of the different air pollutants and thus could not include these factors in the analysis.

There is little published evidence on the association of solar radiation and asthma exacerbations. Most studies have not found a significant association, and the results of studies that did are contradictory.9

In our study, we found an inverse association between solar radiation and the frequency of emergency department visits and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbation. One of the possible explanations is the pathophysiology of asthma, which is based on airway inflammation. Solar radiation, acting as an immunosuppressant through T cell-mediated mechanisms, could have a positive effect on the modulation of chronic pulmonary diseases,18 and thus exert a protective effect against asthma exacerbations. This was consistent a previous study that found an inverse association between solar radiation and the frequency of emergency department visits in adult patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.19 However, the evidence on this association in the paediatric population with asthma is currently insufficient.

Considering other factors, the environmental temperature is the meteorological factor associated most frequently with asthma exacerbations in the literature, predominantly in an inverse direction.6-8,10-12.

However, we did not find a statistically significant association with temperature in our study, which could be due to the type of climate in our region, in which temperatures are mild year-round and vary within a narrow range.

Several studies have analysed the impact of various meteorological factors and pollutants on asthma exacerbations in different age groups, revealing that infants and children under 5 years are less susceptible to these factors compared to older children. However, as age increases, an increasing number of factors have been found to be significantly associated with exacerbations.9,16 A possible reason is that infants and young children spend more time at home sheltered from exposure to environmental factors, so that dust mites in the home and viral infection are the main triggers of asthma exacerbations. In school-aged children and adolescents, due to their lifestyle habits, the association with environmental factors is similar than that observed in adults. Another factor to take into account is the greater adherence to maintenance treatment on account of parental supervision in younger children compared to adolescents, who may have residual airway inflammation and be more vulnerable to the effects of various environmental factors.

In our study, we found differences in the group aged 11 to 16 years, in whom the association was only significant with precipitation, and not with solar radiation. Previous studies have not reported similar results, and this finding could be due to this group being the smallest in our study. On the other hand, we did not find differences that have been previously described in younger age groups.

In our study, the emergency department visits due to asthma in the paediatric population amounted to 4.2% of total de emergency department visits, a percentage that was slightly smaller compared to the reviewed literature. We also found a lower rate of hospital admission (11.8%),4 which could reflect an adequate level of asthma control in our region.

The monthly distribution of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbation exhibited a seasonal pattern (Fig. 1) that had already been described in numerous studies,6,10,13,20-22 with an increase in the spring and an even higher peak in autumn, in late September, around week 38 of the year, with a relative frequency of emergency department visits of 15%.20,21 this pattern may be explained by a combination of factors such as school attendance, exposure to viral agents, meteorological factors and airborne allergens and pollutants.

School attendance, especially at the start of the school year after the summer vacation, , plays a key role in this autumn peak.20 Hervás et al. found that school attendance was independently associated with an increased incidence of asthma exacerbations in children.10 Analysing asthma seasonal patterns in several countries where the school year starts at different times, it becomes apparent that the incidence of asthma exacerbations increases 2 to 3 years from the date school starts.10,20 In our study, the autumn incidence peak essentially started in the fourth week of September, the week after the school year starts. In countries where students return to school in August instead of September, the peak is not as high.20 Thus, it seems that there are other factors at play that contribute to the development of asthma exacerbations in September, which may include infectious or meteorological factors.

Respiratory viruses are closely associated with most asthma exacerbations in children and adults, especially rhinovirus, whose incidence peaks in early autumn.23 A simultaneous increase in respiratory infections and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbations has been described in children during the school year.24 Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that respiratory viruses, and rhinovirus in particular, may play an important role in the epidemic peak observed in autumn. When it comes to the different age groups, the peak is higher and occurs earlier in children, while in older adults it tends to occur one or two weeks later.20 A possible explanation for this lag is the role of children and youth attending school as the main vectors of transmission of the infectious agents involved in the asthma exacerbations of the rest of the family.

As concerns meteorological factors, a study by Witonsky et al.6 found a negative association between environmental temperature and asthma exacerbations that was stronger in boys and in the autumn, when the decline in temperatures was associated with an increased frequency of emergency department visits. Therefore, meteorological factors may also promote asthma exacerbations in autumn. In a study conducted by Hervás et al.10 that applied logistic regression analysis, the model, which combined meteorological factors and school attendance, could explain 98.4% of the asthma exacerbations in the paediatric age group.

Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesise that the peak observed in September, which coincides and is directly associated with the beginning of the school year, is due to a combination of factors, such as weather conditions and an increased exposure to respiratory viruses.

The increase in asthma exacerbations that occurs in the spring seems to be associated with an increased exposure to specific airborne allergens. A previous study found a statistically significant association between pollen counts and the volume of emergency department visits due to asthma, an association that was stronger in the spring months.6

Still, there are several limitations to our study. First of all, its retrospective design, with the intrinsic limitations that it carries. Our results cannot be extrapolated to other populations with different sociodemographic, environmental or climate characteristics. In addition, we did not analyse other factors that could contribute to asthma exacerbations, such as respiratory viruses, airborne allergens and environmental pollutants.

Since the diagnosis of asthma exacerbation is chiefly based on the clinical presentation, it may be difficult to differentiate exacerbations from viral respiratory infections. To minimise confounding, we excluded infants aged less than 1 year, as it is the population with the highest incidence of bronchiolitis. Notwithstanding, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the cases included in the study were cases of viral infection.

This is the second study conducted in Spain to analyse the association between weather conditions and asthma exacerbations in the paediatric population.10 However, it is the first conducted in northern Spain, a region with oceanic climate.

CONCLUSION

Our study corroborated the seasonal pattern in asthma exacerbations previously described in the paediatric population. We found a statistically significant inverse correlation between precipitation and solar radiation in an oceanic climate, on one hand, and the number of emergency department visits and hospital admissions due to asthma exacerbation, on the other.

Research on this subject is clinically relevant because knowledge of the weather conditions that contribute to asthma exacerbations in the paediatric population would allow us to make specific recommendations to at-risk groups in order to minimise exposure to those environmental triggers. It would also allow health care providers to anticipate potential increases in the volume of emergency visits and hospital admissions and reorganise resources as needed. Lastly, knowledge of characteristic seasonal patterns allows optimization of maintenance therapy, and it is essential that patients at risk who discontinue maintenance inhaled corticosteroid therapy in the summer resume treatment before returning to school in the autumn.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article. The study did not receive any form of funding. Partial findings from the study were presented at the XXV Annual Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, held online between March 3 and 6, 2021.

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to the development of the published manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

CIMA: Centro de Investigación del Medio Ambiente (Centre for Environmental Research) · IQR: interquartile range · SD: standard deviation · SEIP: Sociedad Española de Urgencias Pediátricas (Spanish Society of Paediatric Emergency Medicine)

REFERENCES

- Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. In: Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). 2021 [online] [accessed 26/04/2023]. Available at: https://ginasthma.org/

- Carvajal Urueña I, García Marcos l, Busquets Monge R, Morales M, García de Andoin N, Batlles Garrido J, et al. Variaciones geográficas en la prevalencia de síntomas de asma en los niños y adolescentes españoles. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) fase III España. Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:659-66.

- Guía Española para el Manejo del Asma (GEMA) 5.0 [online] [accessed 26/04/2023]. Available at www.gemasma.com.

- Mintegui S, Benito J, González Balenciaga M, Fernández A. Impacto de la intensificación del tratamiento en urgencias del niño con asma sobre la hospitalización. Emergencias. 2003;15:345-50.

- D’Amato G, Holgate ST, Pawankar R, Ledford DK, Cecchi l, Al-Ahmad M, et al. Meteorological conditions, climatic change, new emerging factors, and asthma and related allergic disorders. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. World Allergy Organization Journal. 2015;8:25.

- Witonsky J, Abraham R, Toh J, Desai T, Shum M, Rosenstreich D, et al. The association of environmental, meteorological, and pollen count variables with asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations in the Bronx. Journal of Asthma. 2019;56:927-37.

- Tosca MA, Ruffoni S, Canonica GW, Ciprandi G. Asthma exacerbation in children: relationship among pollens, weather and air pollution. Allergol Inmunopathol (Madr). 2014;42:362-8.

- Yu HR, Lin CH, Tsai JH, Hsieh YT, Tsai TA, Tsai CK, et al. A multifactorial evaluation of the effects of air pollution and meteorological factors on asthma exacerbation. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:4010.

- Lam HC-yu, Li AM, Chan EY-yang, Goggins WB. The short-term association between asthma hospitalisations, ambient temperature, other meteorological factors and air pollutants in Hong Kong: a time-series study. Thorax. 2016;71:1097-109.

- Hervás D, Utrera JF, Hervás Masip J, Hervás JA, García Marcos l. Can meteorological factors forecast asthma exacerbation in paediatric population? Allergol Inmunopathol (Madr). 2015;43(1):32-6.

- Yousif MK, Al Muhyi AA. Impact of weather conditions on childhood admission for wheezy chest and bronchial asthma. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019;33:89.

- Garty BZ, Kosman E, Ganor E, Berger V, Garty l, Wietzen Z, et al. Emergency room visits of asthmatic children, relation to air pollution, weather, and airborne allergens. Ann Allergy Asthma Inmunol. 1998;81:563-70.

- Ivey MA, Simenon DT, Monteil MA. Climatic variables are associated with seasonal acute asthma admissions to accident and emergency room facilities in Trinidad, West Indies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003; 33:1526-30.

- Hashimoto M, Fukuda T, Shimizu T, Watanabe S, Watanuki S, Eto Y, et al. Influence of climatic factors on emergency visits for childhood asthma attack. Pediatr Int. 2004;46:48-52.

- Kwon KW, Han YJ, Oh MK, Lee CY, Kim JY, Kim EJ, et al. Emergency department visits for asthma exacerbation due to weather conditions and air pollution in Chuncheon, Korea: A case-crossover analysis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8:512-21.

- Xirasagar S, Lin HC, Liu TC. Seasonality in pediatric asthma admissions: the role of climate and environmental factors. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:747-52.

- Villeneuve PJ, Leech J, Bourque D. Frequency of emergency room visits for childhood asthma in Ottawa, Canada: the role of weather. In J Biometeorol. 2005;50:48-56.

- Schwarz T, Schwarz A. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:560-4.

- Ferrari U, Exner T, Wanka ER, Bergemann C, Meyer Arnek J, Hildenbrand B, et al. Influence of air pressure, humidity, solar radiation, temperature and wind speed on ambulatory visits due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Bavaria, Germany. Int J Biometeorol. 2012;56:137-43.

- Johnston NW, Sears MR. Asthma exacerbations epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:722-8.

- Sears MR, Johnston NW. Understanding the September asthma epidemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:526-9.

- Khot A, Burn R, Evans N, Lenney C, Lenney W. Seasonal variation and time trends in childhood asthma in England and Wales 1975-1981. British Medical Journal. 1984;289:235-7.

- Gwaltney JM, Hendley JO, Simon G, Jordan Jr WS. Rhinovirus infections in an industrial population. I. The occurrence of illness. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:1261-8.

- Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, Smith S, Campbell MJ, Josephs LK, et al. The relationship between upper respiratory infections and hospital admissions for asthma: a time-trend analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:654-60.