Vol. 24 - Num. 94

Original Papers

Impact of sickle cell disease on the families of affected patients. Qualitative study of their experiences, perceptions and needs

Ana Bernat Nogueraa, Ainhoa Iscar Ortsb, Ana Mascaró Garcíac, Xènia Chela Álvarezd, Trinidad Planas Juane

aPediatra. CS Son Gotleu. Palma . Islas Baleares. España.

bEnfermera. CS Son Gotleu. Palma. Islas Baleares. España.

cMediadora cultural. CS Son Gotleu y Escuela Graduada. Palma. Islas Balerares. España.

dSocióloga. Unidad de Investigación de Atención Primaria de Mallorca. Palma. Islas Baleares. España.

eEnfermera. CS Son Gotleu. Palma de Mallorca. España.

Correspondence: A Bernat. E-mail: ana.bernat@ibsalut.es

Reference of this article: Bernat Noguera A, Iscar Orts A, Mascaró García A, Chela Álvarez X, Planas Juan T. Impact of sickle cell disease on the families of affected patients. Qualitative study of their experiences, perceptions and needs. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2022;24:e207-e215.

Published in Internet: 20-06-2022 - Visits: 12638

Abstract

Introduction: sickle cell disease is a genetic disease that mainly affects the population of African ancestry. It requires repeated and protracted hospitalizations thereby impairing quality of life. The impact of the disease in life is worse in socially vulnerable individuals. This study aimed to establish the concerns, beliefs and needs of the families of children and adolescents affected by sickle cell disease, their knowledge of sickle cell disease, the psychosocial impact of the disease, the satisfaction with health care services and the potential stigma surrounding the disease.

Material and methods: qualitative study through interviews with relatives of affected individuals.

Results: we conducted 20 interviews. We explored how families dealt with the disease; the social and family environment; concerns, emotions, and coping strategies; which resources were wanted versus not, and the satisfaction with the care received. The most salient results of the analysis were the impact of the diagnosis, the good level of knowledge about the symptoms and treatment and differences in the knowledge about the causes of the disease. The caregiver role was associated with female sex. Organizing family life and work was a frequent source of stress. We identified concerns about the disease and everyday life, negative and positive emotions and feelings and different coping strategies. Participants expressed the resources they wished for, such as aid for the sick child. They expressed a positive perception of the care received.

Conclusions: in-depth interviews with families of affected individuals help improve our understanding of their experiences and needs, and therefore also improve the care provided to paediatric patients with sickle cell disease.

Keywords

● Quality of life ● Sickle cell diseaseINTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a chronic disease that causes acute complications. It is an inherited haemoglobinopathy characterised by the presence of sickle haemoglobin (HbS). The disease has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. It mainly affects individuals of African origin.1,2 Due to current migratory patterns, it has become a global disease.3,4 It is estimated that approximately 300 000 children are born with SCD each year,3 and SCD is the most frequent genetic disorder identified in newborn screenings in several countries.2 In some regions of Africa, 50% of affected patients die before age 5 years, and there are no global survival data.5

The complications of SCD result from haemolysis and/or vascular occlusion, causing anaemia, functional asplenia, strokes and pain crisis. The complications may be triggered by infection, dehydration, changes in temperature or stress, or may not have a clear trigger.2,3 Affected individuals require multiple hospitalizations that are frequently protracted, chronic treatment and continuous visits to the hospital. Early diagnosis,6 vaccination, antibiotic prophylaxis, chronic transfusions, hydroxyurea, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and multidisciplinary care have significantly decreased morbidity and mortality in these patients2 and contributed to an increase in life expectancy. New treatments, such as crizanlizumab and voxelotor, could do the same.

Sickle cell disease has repercussions at the individual, family, social and occupational levels,2-4,7-12 and reduces the quality of life of affected individuals and their families.2,13,14 Many patients experience social isolation, concealing the disease in the belief that it is a punishment.3,8,11 Several studies have reported that comprehensive care with adequate coordination between care levesl could improve the quality of life of paediatric patients and their families3,10,11,15 and increase knowledge of the disease,3,6 psychological support and contact with other affected families.3,8,11 It could be said that improving support to families is an important element in the management of SCD.14

Since this disease is more prevalent in a population that is more vulnerable in the current sociodemographic context, it is considered that it merits especial attention to ensure equity.

The aim of our study was to learn the concerns, beliefs and needs of the families of children in care, their knowledge of the disease, their psychosocial problems and their experiences related to SCD, in addition to the stigma and myths surrounding this disease, and their relationship with the health care system.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study with a phenomenological approach through individual semi-structured interviews with relatives of patients aged less than 14 years given a diagnosis of SCD before 2016.

Participants were selected through the review of the patient record databases of Hospital Son Espases and the Hospital Son Llàtzer, the only centres offering specialised followup for SCD in the Balearic Islands. The research team contacted a relative of each patient (2 attempts at 2 different times of day) to explain the study and invite them to participate. When the relative accepted, an appointment was scheduled to conduct the interview, adapting the location and timing to the relative’s preferences. Participants were provided with an informational leaflet, and we obtained their signed informed consent to participation. When the interview was completed, a gift was given to each family to express our appreciation. The script of the interview was based on the goals of the study and the findings of a literature review. The dimensions explored in the interview were: knowledge of the disease, coping, perception of care and perception of the present and future. We also collected information on sociodemographic variables (such as the relationship to child, country of origin or ethnicity).

The interviews were held between September 2017 and August 2018, lasted between 15 and 60 minutes, were recorded (audio only) and transcribed verbatim, assigned a code and saved in encrypted files devoid of personally identifiable information to ensure anonymity. Most interviews were conducted in Spanish. Some were conducted in English by the cultural mediator. The entire process (performance of interviews, transcription and translation) was carried out by the research team.

We performed the content analysis generating a tree of codes based on the objectives and the reading of the interviews. The analysis was conducted separately by 3 researchers. Later on, the results were shared and disagreements resolved, ensuring internal validity. The analysis was performed with the software Nvivo.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Balearic Islands (file no. IB-3428/17).

RESULTS

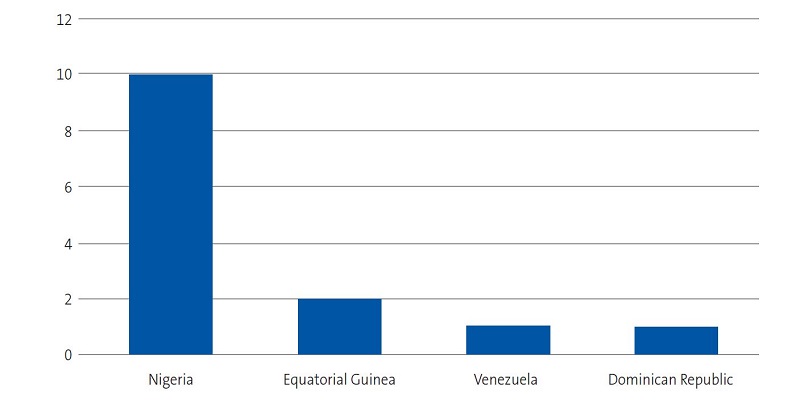

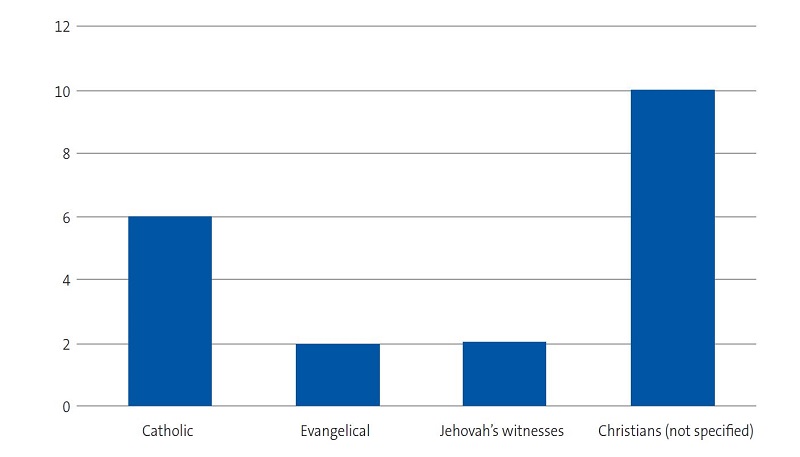

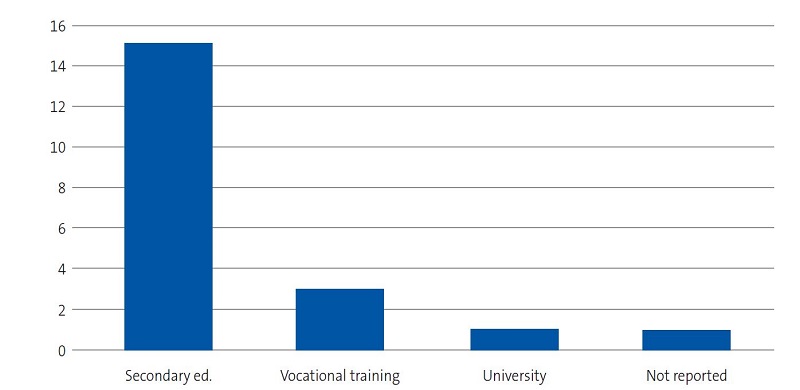

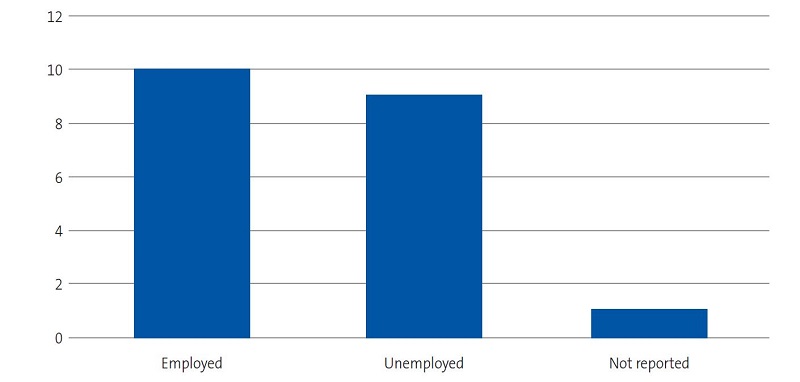

We identified 28 patients aged less than 14 years with a diagnosis of SCD. We succeeded in reaching the families of 15 of the patients (2 of who were siblings), of who the father, mother and/or another relative agreed to the interview. We conducted a total of 20 interviews in a total of 14 families, with participation of 11 mothers, 4 fathers and 5 relatives that lived in the same household. We were able to interview both parents in 3 cases, only the mother in 8 cases, and only the father in 1. The sociodemographic characteristics of the families are presented in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4.

| Figure 1. Study on the concerns, beliefs and needs of families of children with sickle cell disease. Origin of interviewed families |

|---|

|

| Figure 2. Study on the concerns, beliefs and needs of families of children with sickle cell disease. Religion of interviewees |

|---|

|

| Figure 3. Study on the concerns, beliefs and needs of families of children with sickle cell disease. Educational attainment of interviewees |

|---|

|

| Figure 4. Study on the concerns, beliefs and needs of families of children with sickle cell disease. Employment status of interviewees |

|---|

|

We present the results of the study in 4 areas: (1) relationship with the disease, (2) social and family environment and organization of care, (3) concerns, feelings and coping strategies and (4) resources and satisfaction with the care received.

Relationship with the disease

All patients but one were diagnosed in Spain. In general, participants experienced the diagnosis as a shock, and felt fear, disbelief and surprise at the time, in addition to being confused about the situation and the medical explanations. Some cried while they recalled this moment.

“We had a really hard time, because when it first happens you feel like you’ve been pulled out of your life” (P1).

“It was devastating, I felt like dying, like I had no reason to live” (P2).

Nearly all participants had general knowledge of SCD (name, symptoms, that it had to do with the blood, etc). Most have heard the name. Before diagnosis, many did not know the disease. Although only a minority stated that it was a genetic disorder, all interviewees but one had undergone genetic testing to rule out the disease or carrier status. Some of them explicitly stated that there was no cure for the disease, although in other interviews we identified a struggle with comprehending the concept of chronic disease.

“From what I’ve studied I understand that if you’re an AS person it is not good to have children with another AS person because you may have an SS child that has sickle cell disease [in English in original statement]” (Participant 1 [P1]).

“It’s not a disease that you’d consider contagious” (P10).

“It’s a disease that, first, cannot be cured” (P10).

Those who did not know it, after the diagnosis in a relative, learned that there were cases in their country. Three families reported that there were more cases of SCD in the family and explained that the information they received in Spain differed from the information given in their country of origin.

“The anaemia they know is different, what they know is the severe part, that comes suddenly” (P14).

“This disease is frequent in Africa, I’ve not seen it in white people” (P2).

Practically all could identify the warning signs and were aware of the importance of treatment.

“The eye can look yellow, and when the body feels very weak, or if my kid says “mom it hurts here”, we run to the hospital, or with high fever, we run to the hospital” (P1).

“[My child] has to drink a lot of water, and can’t do exercise that’s very, very hard” (P8).

Family environment and organization of care

All Nigerian participants of Edo ethnicity had chosen not to explain to their social circle that their child was sick, and most kept this information restricted to the nucleus of the family (mother and father). The only Nigerian mother of Urhobo ethnicity did not report having any issues discussing the disease of her daughter. Families of other ethnicities reported they had informed the entire family and the school.

“I don’t want Africans to know, I don’t want them to know all about my son. I don’t want people from my country to know cos our people will mock you” (P2).

In most cases, the main caregiver was the mother or a woman, independently of employment status. The mother was also the carer that stayed with the patient during hospital stays, while also continuing to care for the siblings and with house chores. This is a source of stress in the organization of the family. Four women reported they were solely responsible for the care of the child, while 9 said they received some form of help. One woman reported that her husband not only did not help, but that asking him for help caused further stress and complications.

“Men are not like women, if the man is home or the woman is home makes a difference, because you come here to care for the kid during the day or at night, then I go home to cook, care for everyone else, do laundry, cook to put food away in the fridge, and then you come home and he does not understand this” (P3).

Since mothers are the primary caregivers, they are the ones that jeopardize their employment the most to provide care. To attend health care visits, they ask for time off at work or schedule them during their time off work. In one case, the interviewee was looking for a job whose hours would be compatible with caring for the child.

“When he gets a fever I go to him quickly. I’ve had some issues with the company, they tell me ‘you have to let us know ahead of time’ and I say, ‘yes, but my son goes first, I cannot let you know beforehand if he gets sick at midnight.’” (P4).

“If she has an appointment, say tomorrow or in a week (…) if it’s not my day off, I can’t or (…) I’ll talk to my boss to see if they give me the time off to go pick her up, take her to the doctor and come back to work.” (P3).

When men help, they play a secondary role, complementing the activities of the mother. Only in one case did the father report splitting the care of his daughter evenly with the mother.

“If my wife stays there, I go home, although I don’t know how to cook” (P5).

“My wife is always the one that makes the visits” (P14).

“I would say that she [the mother] takes better care of the child” (P5).

The two families from Equatorial Guinea explained that they shared the care of the child within the extended family, as the parents were not in Majorca, although the main caregiver was a woman.

Concerns, feelings and coping strategies

The main concerns identified in the study had to do with the pain and suffering of the family member, the potential for a premature death, uncertainty about the future and the possible adverse effects of treatment. Other less frequent concerns were school life and the potential impact on fertility in girls. Some Nigerian families (Edo and Urhobo people) reported not feeling worried because the child looked well, they were adhering to the followup correctly and they trusted the treatment and God.

“This disease makes me worry so much, and with all this suffering, I suffer with it” (P1).

“Sometimes I wonder if my child is going to die” (P12-13).

“I’m not worried now, we have medication, and everything is quite, quite well” (P6).

Most of the emotions reported were negative: fear, worry, uncertainty and sadness. Participants also expressed positive feelings such as trust, gratefulness, happiness when they see the child is well, reassurance due to the quality of the care and from observing improvement with medication. Many participants hoped that things would improve in the future.

“I’m always scared” (P2).

“When she’s sick, sometimes I feel sad” (P5).

“Whenever they tell me (…) that he’s doing better, I feel happy” (P2).

The interviews revealed factors that help cope better with the disease:

- Belief and hope that God will help, although in one case the mother expressed that the disease is a punishment from God. “God will help” (P12-13), “God can do anything, taking pills and all that… the rest is up to God, so there is no need to worry” (P14), “Why does God do this with people’s lives?” (P9).

- Medical followup: the information, advice and followup by health providers are reassuring. “They gave me hope, when he gets sick at home, I feel that he’ll get better when he gets to the hospital” (P2).

- The love toward the child and the support of the family are a source of strength. “She is my joy” (P9), “He’s been, how could I say? a loved boy, and with all that love (…) we give it all” (P11).

- Denial of the disease. “I don’t believe in disease” (P3).

Resources and satisfaction with the care received

Participants expressed satisfaction with the care received: they reported having good rapport with and trust in health care providers. Most families had little social or family support. Only 2 families reported receiving support from friends. A single participant received support from volunteers during hospitalizations through a non-governmental organization, and perceived this help positively. Three families reported receiving some form of financial assistance.

“People like you have helped me a lot” (P4).

Many participants would like to have food delivered during hospitalizations or be able to go home to get food. They also would like free medication, assistance with transportation to the hospital, the recognition of SCD as a chronic disease eligible for any types of assistance that this entails, early turnaround of test results, a reduction in the number of hospital visits and the ability to take days off from work to devote to the care of the patient. Two interviewees expressed a desire for psychological support and greater empathy. One would prefer to have providers communicate in English to be able to understand explanations better. They expressed satisfaction that health care was free and the medication inexpensive.

“It would be helpful if we could have someone that could take charge [of my sick child] when I’m not available” (P10).

“These children (…) I see that they have not made their situation legal, with all they are going through, so the families have to struggle everyday” (P11).

When asked explicitly whether they would be interested in receiving education about the disease and creating a support group with other families, most expressed an interest. However, Edo families would not attend if other families of Edo descent or from the same country were to participate, arguing that the others would talk about their problems and could use this personal information to harm them.

About the support group: “[Yes,] to give [us] courage… but not if they are Nigerian” (P9); “If [another family] has more experience than me, they can help me, I can learn from them (…) I can also share my experience with them” (P6).

About the training: “I think that the more one knows, the better” (P8); “This way I can worry less” (P9).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that the diagnosis of SCD is a traumatic event that causes significant anxiety. We found adequate knowledge of the symptoms and the importance of treatment, but a relative ignorance of the genetic and chronic nature of the disease. Participants expressed worry about the future, difficulties with organization at home and at work (especially mothers, the primary caregivers), little social support and, in some instances, also little support from family. We detected a degree of isolation in the effort to keep the disease secret, which was more evident in Nigerian families of Edo ethnicity. In general, the relationship of the families with the health care system was satisfactory, although we identified several needs that we belief should be taken into account.

The shocking experience of receiving the diagnosis of SCD and the exposure to various negative stimuli from that moment, leading to an increase in symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients and families, has been previously described in other studies.3,6-10 The care of the patient mainly falls to the mother or another woman, which probably amplifies existing gender inequalities, as women experience the greatest impact on their work, caregiving activities and house chores, creating difficulties in organization, especially during acute crises. Different studies have evinced this situation.3,11,13 These difficulties are frequently exacerbated by the migrant status and vulnerable socioeconomic situation of these women.

The deficient knowledge of the genetic cause and chronicity of SCD may be due to the reluctance to discuss health issues in the family, which was particularly marked in families of Edo ethnicity. This was consistent with the findings of other studies, which have shown that many families keep the disease a secret, suffer social isolation and believe that the disease is a punishment to them, which is accompanied by feelings of guilt.2,3,11,12

The main limitation of our study was the low recruitment and underrepresentation of male participants, which could be accounted by the absence of the father or a lower paternal involvement in the care of the child. There were also cultural and language barriers, which we minimised by including a cultural mediator in the research team. We think there may be a risk of bias when we asked about the care received, as the interviewers were involved in the delivery of care for a family member.

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that paediatric care should focus on the entire family unit to guarantee the overall health of children. After analysing the interviews, and although this type of qualitative research is not design to extrapolate results to the population, we believe that the treatment plan of these patients should take into account aspects like poor social support and potentially precarious employment, in addition to the ethnicity, customs and beliefs of the family to better understand their conception of the disease and improve communication, for which it may be helpful to have access to a professional mediator. Our findings suggest opportunities for improvement in care delivery, such as offering help during hospitalizations and providing financial assistance (for instance, the financial assistance benefits established for caring for a minor with cancer or another severe disease by Royal Decree 1148/2011, of 29 July) and work-family balance in the context of the disease. Interventions suggested as potentially interesting included offering families participation in trainings to increase their knowledge of the disease and/or establishing a support group with other families to increase social support, although it must be taken into account that these suggestions were made by health care professionals and not the families, so we ought to reinforce the importance of approaching the needs of families taking into account their cultural background.

We conclude that multidisciplinary care, with performance of in-depth clinical interviews focused on the family and its circumstances, can only improve the quality of life of individuals with SCD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

Funding. Study funded by the Primary Care Research Commission of Majorca through the IV Internal Competition for Grants to Support Research in Primary Care Health in Balearic Islands 2016 (PI003/17).

ABREVIATURAS

SCD: Sickle cell disease.

REFERENCES

- Rives Sola S. Enfermedad de células falciformes: papel del pediatra. An Pediatr Contin. 2013;11:123-31.

- Enfermedad de células falciformes: guía de práctica clínica. In: Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología pediátricas (SEHOP). 2019 [online] [accessed 10/06/2022]. Available at www.sehop.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Gu%C3%ADa-SEHOP-Falciforme-2019.pdf

- Keane B, Defoe l. Supported or stigmatised? The impact of sickle cell disease on families. Community Pract. 2016;89:44-7.

- Garcia Arias MB, Cantalejo López MA, Cela de Julian ME, Bravo CR, Galaron GP, Belendez BC. Enfermedad de células falciformes: registro de la Sociedad Española de Hematología Pediátrica. An Pediatr (Barc) 2006;64:78-84.

- Guía de práctica clínica sobre Enfermedad de Células Falciformes Pediátrica. In: Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología pediátricas (SEHOP). 2010. [online] [accessed 10/06/2022]. Available at www.sehop.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/GU%C3%8DA-FALCIFORME-SEHOP-2010.pdf

- Fernández Águila J, Pérez Cogle A, Fragoso M, Rivero Jiménez R. El diagnóstico temprano de la anemia falciforme: un problema no resuelto en África negra. Rev Cubana Hematol Inmunol Hemoter. 2012;28:195-7.

- Serrano Patten AC, Louro Bernald I, Vargas Flores J, Osorio Caballero I, Chavez Perez Teran M. Situacion de salud en familias de niños con padecimiento de anemia drepanocitica en Cuba. Rev Elect Psicol Iztacala. 2008;11:26-55.

- Nika ER, Mabiala Babela JR, Moyen G, Kambouro J. Vécu psychosocial des mères d’enfants drépanocytaires. Arch Pédiatrie. 2016;23:1135-40.

- Dommergues JP, Gimeno l, Galacteros F. Un pédiatre à l’écoute de jeunes adultes drépanocytaires. Arch pédiatrie 2007;17:1115-8.

- Curado MA, Nakheiro MI, Gomes MC, Videira M, Dias P, Gaspar C, Vaz E. Cuando duele… duele de veras. El niño con Drepanocitosis. Enferm Global. 2006;9:1-15.

- Luboya E, Tshilonda J-CB, Bothale Ekila MB, Aloni MN. Repercussions Psychosociales de la drépanocytose sur les parents d'enfants vivant à Kinshasa, République Démocretique du Congo: une étude qualitative. Pan African Med J 2014;19:5.

- Allen TM, Anderson LM, Rothman JA, Bonner MJ. Executive functioning and health-related quality of life pediatric sickle cell disease. Child Neuropsychol. 2017;29:889-906.

- MartínezTriana R, García Hernández A, Guerra González EM, Machado Almeida T, Reytor Alfonso K. Efecto de la drepanocitosis sobre la calidad de vida. Rev Cubana Hematol Inmunol Hemoter. 2015;31:277-87.

- Sehlo MG, Kamfar HZ. Depression and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: the effect of social support. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:78.

- Cervera Bravo A, Cela de Julián ME. Anemia falciforme. Manejo en Atención Primaria. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2007;9:649-68.