Vol. 24 - Num. 93

Original Papers

Risk of COVID-19 infection based on the type of contact and family income

Álvaro Baeta Ruiza, José M.ª Mengual Gilb, Beatriz Ortega Aguilarc, Sonia Duce Camachod, Nuria García Sánchezb, Neelam Mithumal Dadlani Dadlani a, Paloma del Carmen Jolín Garcíab

aMIR-Pediatría. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Zaragoza. España.

bPediatra. CS Delicias Sur. Zaragoza. España.

cMIR-Medicina de Familia. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Zaragoza. España.

dEnfermera. CS Delicias Sur. Zaragoza. España.

Correspondence: A Baeta . E-mail: a.baeta11@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Baeta Ruiz A, Mengual Gil JM, Ortega Aguilar B, Duce Camacho S, García Sánchez N, Dadlani Dadlani NM, et al. Risk of COVID-19 infection based on the type of contact and family income. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2022;24:31-7.

Published in Internet: 28-03-2022 - Visits: 13929

Abstract

Purpose: during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Zaragoza, we studied the paediatric contacts of COVID-19-positive patients to estimate the risk of infection after exposure to a positive child or adult and the risk of infection based on household income.

Methods: we conducted a descriptive study of all paediatric patients that were close contacts of individuals with COVID-19 in the Delicias Sur Primary Care Centre (Zaragoza, Spain) between July and August 2020. We also analysed the most frequent symptoms, visits to the emergency department, diagnostic tests, contact with a child versus an adult with COVID-19 and household income.

Results: a total of 292 patients had had close contact with individuals with COVID-19; 218 of them had positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results. When we analysed the close contacts, we found that 10.94% of patients that tested positive had been in close contact with a child with COVID-19 and 89.06% with an adult with COVID-19. The estimated risk of infection after exposure was 29.8% in the case of close contact with a child with COVID-19 compared to 46.53% when it came to close contact with an adult case. The risk of infection was higher in patients with an annual household income of less than €18000 (47.9%) compared to patients with a higher annual household income (27.6%).

Conclusion: the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection was higher in patients that had close contact with adult cases and with lower household incomes.

Keywords

● Contact tracing ● COVID-19 ● Household income ● Infectious disease transmission ● SARS-CoV-2INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the infectious disease caused by the coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2, which was first detected in China and rapidly spread to the rest of the world. This virus causes a respiratory infection that can be transmitted from person to person in airborne droplets issued from the nose or mouth of an infected person through coughing, sneezing or speaking, through surfaces contaminated by the virus or aerosols that may remain suspended in air for several hours. Some authors have asserted that aerosol transmission may account to up to 75% of cases.1

In the paediatric population, the evidence shows that positive cases tend to result from contact with an infected adult, and household transmission plays a very important role. In addition, children infected by SARS-CoV-2 tend to develop milder forms of disease and fewer symptoms compared to adults.2,3

From the detection of the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in China, concern emerged as to how the virus could affect the paediatric population and the role played by children in the transmission chain. This led to the implementation of extraordinary measures in Spain, such as the closure of schools and confinement to the home for approximately 70 days, a measure lifted on June 20, 2020. In the present work, the period under study comprised July and August, when there were no restrictions to free movement or confinement mandates, and coinciding with the summer vacation from school for the paediatric population.

The primary objective of the study was to assess whether paediatric patients in our area had acquired the infection following close contact with an adult or a child positive for COVID-19 and to assess the risk of transmission based on household income, which we assessed through the pharmacy co-pay bracket code in the public health system health insurance card (HIC). As secondary objectives, we analysed the development of symptoms in patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis, the type of presented symptoms, visits to the emergency department, performance of diagnostic tests and need of hospital admission.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study by reviewing the electronic health records of patients managed at the Delicias Sur Primary Care Centre in Zaragoza (Spain). We included patients with diagnostic code A77 or A23 in the OMI electronic health record database, corresponding to contact of infectious individual and confirmed COVID-19 infection.

The study period covered 2 months (July-August 2020), and we included children aged 1 month to 18 years.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 was considered the gold standard for diagnosis of COVID-19.

We defined close contact as a patient exposed to an individual with COVID-19 at a distance of less than 1.5 m for more than 15 minutes without use of masks.

The exclusion criteria for the study were: age less than 1 month or greater than 18 years, lack of performance of SARS-CoV-2 PCR test in a nasopharyngeal sample and inability to identify the contact of the patient, independently of the results of the PCR test.

The primary outcome was the result of the SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. The secondary variables under study were age, presence of symptoms (fever, cough, rhinitis etc), visits to emergency department in referral hospital, need of diagnostic tests, need of hospital admission, contact with an adult with COVID-19 or a child with COVID-19 and the household income level based on the pharmacy copay code in the HIC, which is determined based on the income, employment status and socioeconomic status of the patient, and is therefore a direct indicator of income level: HIC 001, social, state or disability pension or unemployed not eligible for unemployment benefits; HIC 002: employment-based pension recipient; HIC 003: currently employed with annual income < €18 000; HIC 004: currently employed with annual income between €18 000 and €100 000; HIC 005: currently employed with annual income > €100 000; HIC 006: private pension beneficiary and current or past state employee (civil servants in public administration, armed forces and judiciary).

In the descriptive analysis of the data, we calculated measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean, median and standard deviation) for the age of patients and, in the case of qualitative variables, absolute frequency and percentage distributions. Subsequently, we analysed observed differences by means of the χ² test, defining statistical significance as a p-value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Initially, 300 patients had the diagnostic codes that defined eligibility recorded in their electronic health records, of who 8 met the exclusion criteria, so the final sample size of the study was 292. These 292 patients were close contacts of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mean age of the sample was 8.53 years, with a median of 9 years, a mode of 14 years and a standard deviation of 5.05. Of the 292 patients, 139 were female (48%) and 153 male (52%).

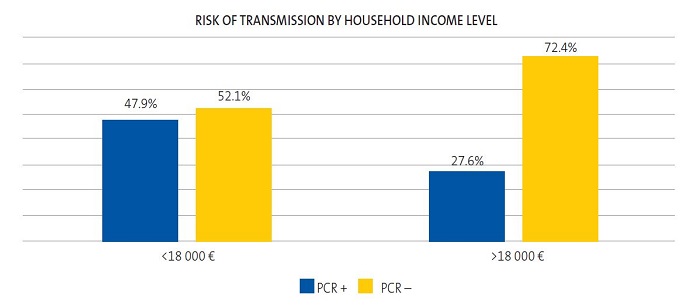

A SARS-CoV-2 PCR test was performed in every patient and turned out positive in 128 children, that is, 43.84% of the sample. In the subset of patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, 36.72% (47 patients) had some type of symptom, while 63.28% (81 patients) remained asymptomatic. In the group of the 47 symptomatic patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, 15 different symptoms had been documented, the most frequent of which was fever (27 patients), followed by cough (9 patients) and headache (9 patients) (Figure 1). Of all the symptomatic patients in the study (60 patients), 21.67% (13 patients) had negative results in the SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, while 78.33% (47 patients) had positive results.

| Figure 1. Graphic representation of the symptoms presented by patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result. It includes 15 categories. The “other” category includes irritability and chest pain |

|---|

|

In the group of symptomatic patients, 9 (19.15%) required assessment in the emergency department, and all turned out positive for SARS-CoV-2. Out of these 9 patients, only 3 underwent additional diagnostic tests (plain chest radiograph). None of the patients required hospital admission.

One of the main aims of our study was to assess whether the close contact with COVID-19 had been an adult or a child. In the total sample, 13.35% (39 patients) had been in close contact with a positive child, and 83.90% (245 patients) with a positive adult. Eight patients (2.75%) had simultaneously been in close contact with both and adult and a child with COVID-19. Of the patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, 10.94% (14 patients) had had contact with a child, and 89.06% (114 patients) with an adult.

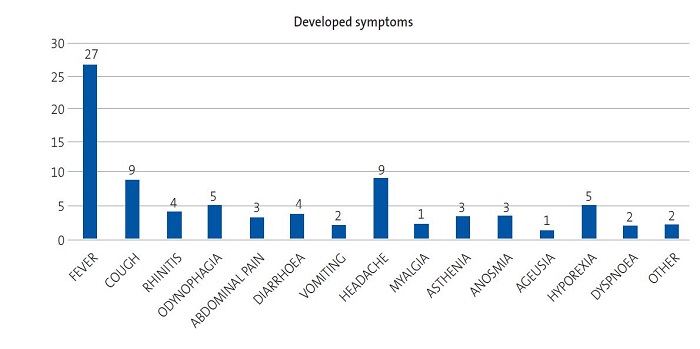

The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, that is, the probability of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test after being in close contact with a child with COVID-19, was 29.8%, with the probability of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test following close contact with an adult case was 46.5% (Figure 2), a difference that was statistically significant. Furthermore, 70.2% of children with close contact with a child with COVID-19 and 53.5% of children with close contact with an adult with COVID-19 did not acquire the infection.

| Figure 2. Distribution of the risk of infection following close contact (exposure) with a child versus an adult with COVID-19 |

|---|

|

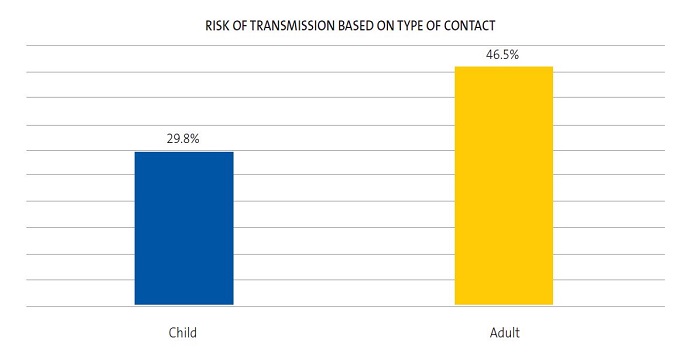

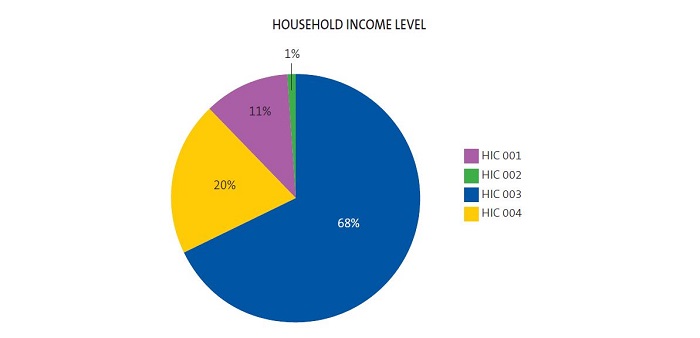

We analysed the sample based on household income by means of the pharmacy copay code displayed in their HIC. We found that 80% of the catchment population of the Delicias Sur Primary Care Centre had a copay code of HIC 003 or lower, which corresponds to an annual income of less than €18 000, while 20% had the code HIC 004, corresponding to an annual income of €18 000 to €100 000. None of our patients had the TSI 005 code (annual income > €100 000) (Figure 3). Of the patients with household incomes of less than €18 000 that were close contacts of cases of COVID-19, 47.9% (112 patients) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, while the PCR test was negative in 52.1% (122 patients). In contrast, of the patients with household incomes greater than €18 000 that were close contacts of cases of COVID-19, 27.6% (16 patients) had positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests, while the test was negative in 72.4% (42 patients) (Figure 4). This difference was statistically significant.

| Figure 3. Distribution of the total sample (292 patients) by household income level, assessed by means of the pharmacy copay code in the health insurance card |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

The main strength of our study is that it included every child diagnosed with COVID-19 in our health district during the period under study, which reduces the risk of selection bias.

The main limitation is that the data were collected retrospectively, and that the epidemiological surveys and database used to collect the data were not designed specifically for the study. The barriers that exist for communication with the immigrant population, which amounts to a substantial proportion of the total population of our catchment area, is another aspect that must be taken into account.

Our study shows that children are less likely to have a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test following contact with an infected child compared to contact with an infected adult. Besides the hypothesised lower infectiousness of children,4 other factors that may be at play in this outcome are: the study period, July and August, 2020, coincided with the summer vacation in primary and secondary education schools, when paediatric patients spend more time at home with their families and contacts with same-age peers occur more frequently in the context of leisure activities that take place out of doors. In addition, in these months the weather in Zaragoza is warm and dry, with more hours of sunlight a day and thus increased exposure to UV radiation that may reduce the transmissibility of the virus, although the evidence on the subject is insufficient to confirm it.5 A study by T. C. Jones et al.6 assessed whether viral loads varied with patient age in patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, but did not find statistically significant differences. The current evidence is also insufficient to draw conclusions regarding the hypothesis that adult patients, who tend to be more symptomatic, are more likely to transmit disease.

Our sample was comprised of patients that were close contacts of individuals with COVID-19 in the caseload of the Delicias Sur primary care centre. The neighbourhood of Delicias in Zaragoza is the most populated and dense neighbourhood in the city, in addition to having the largest immigrant population. The mean household income in Delicias is €27 000 a year, and the mean personal income €10 280 a year, both below the mean in the city of Zaragoza.7

Another potential limitation is the use of the HIC as an indicator of household income, as this parameter is only indicative and not an accurate measure of annual household income, and the ranges comprehended in each category are very broad, especially when it comes to HIC 004, which spans from €18 000 to €100 000 a year. In our sample, 80% of patients came from households with incomes of less than €18 000.

The risk of contagion following exposure to an individual with COVID-19 was greater in patients with a household income of less than €18 000 compared to greater incomes. This difference may be due to a greater difficulty to isolate within the home, as patients in lower-income brackets are more likely to reside in homes that are smaller, have fewer rooms, have more household members or shared by more than one family.

CONCLUSION

The paediatric patients that had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test in our sample remained asymptomatic in 63.28% of the cases. In the subset of symptomatic patients, all patients had mild symptoms, most frequently fever, followed by cough and headache in preadolescent patients.

The patients included in the study, children that had been in close contact with a known case of COVID-19, were at higher risk of acquiring the infection if the close contact was an adult as opposed to a child. We also found a higher risk of transmission in patients with household incomes of less than €18 000 compared to patients with household incomes greater than €18 000. Children in our sample had a 1.5-fold risk of acquiring the infection if exposed to an infected adult compared to an infected child and a 1.5-fold risk of acquiring the infection if the household income was less than €18 000, and these two risks were independent from one another.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study did not receive any external funding.

All authors contributed to the performance of the study and approved the submitted manuscript. BOA and SDC were in charge of data collection and the Introduction section. PCJG and NMDD wrote the Discussion and Conclusion sections. NGS, JMMG and ABR were in charge of the study design and the Material and Methods and Results sections.

ABBREVIATIONS

HIC: health insurance card · PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

REFERENCES

- Anderson EL, Turnham P, Griffin JR, Clarke CC. Consideration of the Aerosol Transmission for COVID-19 and Public Health. Risk Anal. 2020;40:902-7.

- Balasubramanian S, Rao NM, Goenka A, Roderick M, Ramanan AV. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children - What We Know So Far and What We Do Not. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:435-42.

- Laws RL, Chancey RJ, Rabold EM, Chu VT, Lewis N, Fajans M, et al. Symptoms and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Among Children - Utah and Wisconsin, March-May 2020. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020027268.

- Fiel Ozores A, González Durán ML, Novoa Carballal R, Portugués de la Red MM, Fernández Pinilla I, Julio Cabrera Alvargonzález J, et al. Clínica diferencial en niños infectados por SARS-CoV-2, trazabilidad de contactos y rentabilidad de pruebas diagnósticas: estudio observacional transversal. An Pediatr. 2021;94:318-26.

- Paraskevis D, Kostaki EG, Nikiforos A, Thomaidis NS, Cartalis C, Tsiodras S, et al. A review of the impact of weather and climate variables to COVID-19: In the absence of public health measures high temperatures cannot probably mitigate outbreaks. Sci Total Environ. 2021;768:144578.

- Jones TC, Biele G, Muhlemann B, Veith T, Schneider J, Beheim-Schwarzbach J, et al. Estimating infectiousness throughout SARS-CoV-2 infection course. Science. 2021;373:eabi5273.

- Observatorio Urbano de Zaragoza y su Entorno. Zaragoza en datos. Informe global sobre la ciudad y sus distritos. In: Ebropolis [online] [accessed 07/06/2021]. Available at: www.ebropolis.es/files/File/Observatorio/Distritos/DossierZaragoza-marzo2018-Ebropolis.pdf

- Tezer H, Bedir Demirdağ TB. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in children. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50:592-603.

- Munro APS, Faust SN. Children are not COVID-19 super spreaders: time to go back to school. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:618-9.

- Lee B, Raszka WV. COVID-19 Transmission and Children: The Child Is Not to Blame. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e2020004879.

- Posfay-Barbe KM, Wagner N, Gauthey M, Moussaoui D, Loevy N, Diana A, et al. COVID-19 in Children and the Dynamics of Infection in Families. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20201576.