Vol. 23 - Num. 92

Original Papers

Dog bites. Epidemiological analysis (2011-2018) and preventive strategies

Clara C. de Sobregrau Martíneza, Mireia Tugues Alzinab, Beatriz León Carrilloc, Núria Cahís Velad

aMIR-Pediatría. Hospital Parc Taulí . Sabadell. Barcelona. España .

bMIR-Pediatría. Hospital Parc Taulí. Sabadell. Barcelona. España.

cEnfermera. Servicio de Urgencias de Pediatría. Hospital Parc Taulí. Sabadell. Barcelona. España .

dPediatra. Servicio de Urgencias de Pediatría. Hospital Parc Taulí. Sabadell. Barcelona. España.

Correspondence: C C. de Sobregrau. E-mail: ccsobregrau@gmail.com

Reference of this article: C. de Sobregrau Martínez C, Tugues Alzina M, León Carrillo B, Cahís Vela N. Dog bites. Epidemiological analysis (2011-2018) and preventive strategies. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2021;23:365-71.

Published in Internet: 25-10-2021 - Visits: 19652

Abstract

Introduction: dog bites in children continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. The purpose of our study was to describe the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of these accidents in the paediatric population of our area and to propose preventive strategies to reduce their incidence.

Material and methods: we conducted a retrospective study of patients that received care for dog bites in a tertiary care hospital over an 8-year period. We collected data on demographic variables, dog breeds, sites of injury, the relationship between the dog and the child, the treatment received and sequelae.

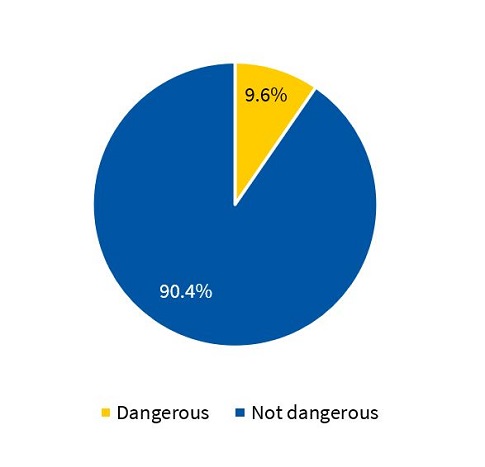

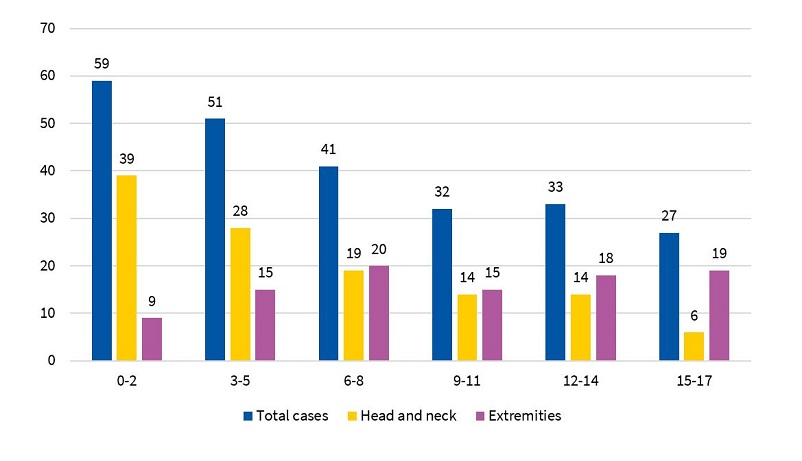

Results: we identified 236 patients, with a mean age of 7 years. Most attacks occurred in spring or summer. In 76% of cases, the child was acquainted with the dog. Only 10% of attacks involved breeds considered potentially dangerous. Fifty-one percent of injuries were in the head or neck and 40% in the extremities. Antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed in 90% of cases. Five percent required admission. Cosmetic sequelae were documented in 15% of patients and psychological sequelae in 10%.

Conclusions: dog bites continue to be a reason for seeking emergency care in the paediatric population, and they are most frequent in children aged less than 6 years. In most cases, the attacking dog was a family pet of a breed not considered dangerous. The persistence of these incidents calls for the implementation of preventive measures to raise awareness in the population and thus reduce the frequency and severity of these injuries.

Keywords

● Animal bites ● Injuries ● PreventionINTRODUCTION

Animal bites cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide and remain an important public health problem.1,2 They are most frequently inflicted by dogs, responsible for 60% to 95% of cases, based on studies conducted in different countries.3-6

Children are the subset of the population at highest risk7 and are the victims in 56% to 70% of cases.8,9 It is estimated that in the population under 12 years, 1% of emergency visits are due to dog bites.9-12

In Spain, approximately 70 000 children are attacked by dogs each year, which corresponds to a mean of 200 cases per day.9

The severity of dog bite injuries varies widely, from mild lesions like haematomas or superficial erosions to severe injuries that may be life-threatening or cause significant complications, including infection or cosmetic or psychological sequelae.7,10,13,14

These incidents are accentuated by their media coverage; there are frequent news of severe or even fatal attacks by dogs of potentially dangerous breeds. While these cases are alarming, the reality of dog bites in our region is quite different.9

The aim of our study was to describe the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of dog bite injuries in paediatric patients in our area, identify associated risk factors and propose primary prevention strategies based on our findings.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study based on the review of health records. We included every patient under 18 years that received care for dog bite injuries in the paediatric emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in the province of Barcelona, Spain, over an 8-year period (2011-2018).

The variables under study were the patient age and sex, date, setting and municipality where the attack took place, relationship of the dog to the patient, dog breed and size, site of injury, need of suture or surgical debridement, use of antibiotic prophylaxis, vaccination status of dog and patient, need of admission and sequelae or complications.

We analysed the retrieved data with the statistical software SPSS. We analysed the association between variables with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Student t test.

This review was approved by the research ethics committee of our hospital.

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 236 patients received care for dog bites in our emergency department, 52% of who were female (Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2). The mean age of the patients was 7 years (range: 1 month to 17 years). The mean annual number of visits for this reason was 29 (range: 18-40), with the frequency of visits remaining stable through time. Sixty-two percent of attacks took place in spring or summer, and 45% on weekends. The dog was known to the patient in 72% of cases, and within this group, 40% were family pets. Although vaccination against rabies is not mandatory in Catalonia, 87% of the dogs had been vaccinated. The breed of the dog was identified by the patient or family 33% of cases. Ten percent of attacks involved dogs of breeds considered potentially dangerous (Doberman, rottweiler, pit bull, American Staffordshire terrier). In 40% of attacks, the dog was large (>20 kg). Eighteen percent of the patients sustained multiple injuries. The face was the area involved most frequently in younger patients (mean age, 6 years) (51%), in contrast to older patients that were more likely to sustain injuries to the extremities (p <0.05): upper extremities (25%) and lower extremities (15%). Ninety-five percent of patients could be discharged home from the emergency department, of who 33% required topical drugs and suturing. Ninety percent received antibiotic prophylaxis, with prescription of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in 95% of them. Only 5% of the patients were admitted to hospital, of who 75% required surgery. Fifteen percent of patients had cosmetic sequelae and 10% psychological sequelae. There were no fatalities.

| Table 1. Epidemiological analysis of dog bites (2011-2018): demographic and clinical characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | |

| N | 236 | |

| Sex | Male | 48.3% |

| Female | 51.7% | |

| Age | 0-2 years | 51 (21.6) |

| 3-5 years | 51 (21.6) | |

| 6-8 years | 41 (17.4) | |

| 9-11 years | 32 (13.6) | |

| 13-15 years | 34 (14.4) | |

| 15-17 years | 27 (11.4) | |

| Season | Winter | 36 (15.3) |

| Spring | 77 (32.6) | |

| Summer | 71 (30.1) | |

| Autumn | 52 (22) | |

| Ownership of dog | Own dog | 84 (39.6) |

| Family dog | 34 (16.1) | |

| Known dog | 34 (16.1) | |

| Unknown dog | 59 (28) | |

| Site of injury | Head or neck | 118 (51.5) |

| Upper extremity | 58 (24.9) | |

| Lower extremity | 38 (16.3) | |

| Trunk | 16 (6.9) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | |

DISCUSSION

Dog bites continue to be a significant problem today, and most cases involve paediatric patients.10,13 They are a common reason for visits to paediatric emergency departments in tertiary care hospitals (about 1% of the total) and are associated with a low rate of hospitalization, as most can be managed at the outpatient level. The incidence of dog bite injuries is estimated at 48 to 100 per 100 000 inhabitants, although it is believed that it may be higher than calculated due to the underreporting of these events.2

The data obtained in our study regarding sex, age, site of injury and complications were consistent with the previous medical literature.1,7,10,13 We found a higher incidence of dog bites in children aged less than 6 years that was associated with greater severity. The most frequent site of injury was the face, and there was a significant association between younger age and this site, probably on account of short stature, a relatively larger head size, the tendency to play on the floor and curiosity.15 The capacity for self-defence, the interpretation of dog behaviour by children and the way children interact with dogs are other key factors.16,17

Although in most cases the injuries are not severe, more than half result in permanent scars, 10% require suturing and 1% to 5% require hospital admission.18

One of the most frequent complications is wound infection. This depends on several factors, such as the type and location of the injury, wound care and individual risk factors.10,19

Tetanus prophylaxis is widely recommended in patients that are not fully vaccinated, but the use of antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial.10,20 To date, there is no evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis can achieve a significant reduction in the development of infection in dog bite wounds,21 although it is recommended that the decision to provide it be individualised based on the factors described above. The antibiotic agent recommended most frequently for prophylaxis is amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.2,14,18,22,23

It is important to document the vaccination status of both the dog and the patient. Spain has been considered rabies-free since 1978.24 However, the management of each case must be individualised, as in many cases the animal is of unknown origin or comes from another country.

In our review, we did not identify any fatalities resulting from dog attacks, but there were patients that experienced cosmetic or psychological sequelae.

We had no access to data on the condition of the animal (whether the dog was wearing a muzzle, training) or on the recurrence of attacks or aggressive behaviours, which are important predictors.

As evinced by the case series in the literature, in more than half of the cases, the attacking dog was known to the victim or family. The role of breed is highly controversial. The breeds considered potentially dangerous (Doberman, rottweiler, pitbull, American Staffordshire terrier, among others) seemed to be involved more frequently in bite injuries. However, caution must be exerted when drawing conclusions. The relative frequency of these breeds in the total canine population must be considered. Dogs of these breeds tend to be large and powerful. Their attacks are characterised by a lack of preceding warning signs, so the victim has no time to react. Another aspect to consider is that the awareness of these breeds may lead to more frequent reporting of aggressive events.12

Thus, based in our findings, known dogs and dogs of breeds considered “not aggressive” are the main problem. While it is true that breed and origin may be associated with a predisposition for aggression, there are other factors that play a role in problematic behaviours. Therefore, in order to reduce the incidence of dog bites, it is important to avoid legislation based solely on breed. In Spain, the legislation changed in 1999 and 2002 to identify potentially dangerous breeds and enacting economic and behavioural regulations for dog ownership.25 Since then, there has been evidence of a decreasing trend in overall dog attacks.

Many dog attacks on humans could be prevented. Given the incidence of dog bites, the associated health care costs and the sequelae experienced by victims, we consider that more preventive measures should be implemented, as suggested by other authors,9 with an emphasis on the education and behaviour of animal carers.

Although most bites result from unprovoked attacks, teaching children how to interact with dogs could help reduce the incidence of these accidents.26 Cognitive-behavioural interventions in the paediatric population have been found somewhat effective in reducing this type of attacks.26 Other authors suggest that educating families and paediatricians would be more effective than educating children,15 placing particular emphasis on the aspects of interaction and supervision. Most injuries occur in children under 5 years, who are cognitively immature, which substantially limits the delivery of educational interventions in this age group.8,27

We advocate the implementation of educational interventions in schools and primary care centres, informing on the dangers of playing with dogs using print and audiovisual content. In some countries, such as the United States, Australia and United Kingdom, educational interventions with simulation on how to interact with dogs have proven feasible and effective in reducing dog attacks.10,20 Another promising intervention that could be useful would be the distribution of guides outlining basic rules to share the home safely with a pet.

Preventive measures should be multifaceted, including policy and legislation as well as education for dogs and humans sharing a household.16

Limitations of the study

Since we performed a retrospective study based on the retrieval of information from health care records in the database of our hospital, the study variables were not documented in every case. For the same reason, we did not include any children that did not seek care in the emergency department. As mentioned above, we had some problems determining the breed of involved dogs. We were also unable to determine whether single dogs were responsible for more than one attack. We are aware that the causes of these accidents are multifactorial. In many cases, the indication of treatment and prophylaxis is determined based on the judgment of the physician in charge of the patient. We may have underestimated the incidence of related complications and sequelae (infectious, psychological, cosmetic), as patients may have sought care at the primary care centre instead of the hospital.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, more clinical and epidemiological studies are required to improve the management, reporting and surveillance of dog bites in order to make more accurate estimates of their incidence. The fact that these accidents continue to happen, chiefly in the paediatric population, and given the sequelae that results from them, calls for the implementation of preventive measures, especially in young children. The results of this review could spur social debate and promote the introduction of targeted preventive measures for implementation in hospital and veterinary care settings, and raise awareness in the community on the risks involved in dog attacks, for the purpose of decreasing their frequency. Protocols for the management of dog bites in paediatric emergency care settings should also be established.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The study was presented at the XXIV Meeting of the Sociedad Española de Urgencias de Pediatría, held on May 9-11, 2019 in Murcia, Spain.

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of the nursing staff of the paediatric emergency department of our hospital. We also thank the department of statistics of the hospital for their help, and Joan Carles Oliva in particular.

REFERENCES

- Gilchrist J, Sacks JJ, White D, Kresnow MJ. Dog bites: Still a problem? Inj Prev. 2008;14:296-301.

- Palacio J, León M, García-Belenguer S. Aspectos epidemiológicos de las mordeduras caninas. Gac Sanit. 2005;19:50-8.

- Berzon DR, Farber RE, Gordon J, Kelley EB. Animal bites in a large city-a report on Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Public Health. 1972;62(3):422-6.

- Matter HC, Sentinella Arbeitsgemeinschaft. The epidemiology of bite and scratch injuries by vertebrate animals in Switzerland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;(14):483-90.

- Knobel Freud H, López Colomés J, Serrano Sainz C, Hernández Vidal P. Mordeduras de animales. Estudio de 606 casos. Rev Clin Esp. 1997;8:560-3.

- Quiles Cosme G, Pérez-Cardona C, Aponte Ortiz F. Estudio descriptivo sobre ataques y mordeduras de animales en el municipio de San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1996-1998. P R Heal Sci j. 2000;19:39-47.

- Sánchez-Vázquez A, Sánchez-Vázquez B. Lesions produïdes per atacs de gossos a infants. Experiència de dos hospitals de la província de Barcelona. Pediatr Cat. 2018;78:136-9.

- Cook JA, Sasor SE, Soleimani T, Chu MW, Tholpady SS. An Epidemiological Analysis of Pediatric Dog Bite Injuries Over a Decade. Pediatr Cong Develop. 2020;246:231-5.

- Méndez RG, Gómez MT, Somoza IA, Liras JM, Pais EP, Nieto DV. Mordeduras de perro. Análisis de 654 casos en 10 años. An Esp Pediatr (Barc). 2002;56:425-9.

- Morzycki A, Simpson A, Williams J. Dog bites in the emergency department: a descriptive analysis. Can J Emerg Med. 2019;21:63-70.

- Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH. Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;279:51-3.

- Sacks J, Sattin R. Bonzo S. Dog Bite-Related Fatalities From 1979 Through 1988. JAMA. 1988;262(11):1489-92.

- Golinko MS, Arslanian B, Williams JK. Characteristics of 1616 Consecutive Dog Bite Injuries at a Single Institution. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56:316-25.

- Mannion CJ, Graham A. Dog bite injuries in hospital practice. Br J Hosp Med. 2016;77:C165-8.

- Duperrex O, Blackhall K, Burri M, Jeannot E. Education of children and adolescents for the prevention of dog bite injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD004726.

- Del Peral Samaniego MP, Costa Roig A, Diéguez Hernández-Vaquero I, Lluna González JM, Vila Carbó JJ. Mordeduras de perro, un problema vigente en nuestro entorno. Cir Pediatr. 2019;32(4):212-6.

- Barton BK, Schwebel DC. The roles of age, gender, inhibitory control, and parental supervision in children’s pedestrian safety. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:517-26.

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of human and animal bite wound infections. Prim Care. 2003;30:25-39.

- Lang ME, Klassen T. Dog bites in Canadian children: a five-year review of severity and emergency department management. Can J Emerg Med. 2005;7:309-14.

- McGuire C, Morzycki A, Simpson A, Williams J, Bezuhly M. Dog bites in children: A descriptive analysis. Plast Surg. 2018;26:256-62.

- Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites (Review). Cochrane Collab. 2010;(2):1-20.

- Brakenbury PH, Muwanga C. A comparative double blind study of amoxycillin/clavulanate vs placebo in the prevention of infection after animal bites. Arch Emerg Med. 1989;6:251-6.

- Goldstein EJC, Citron DM. Comparative activities of cefuroxime, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, enoxacin, and ofloxacin against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria isolated from bite wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1143-8.

- Rabia: Situación de la Enfermedad. In: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación [online] [accessed 19/10/2021]. Available at www.mapa.gob.es/es/ganaderia/temas/sanidad-animal-higiene-ganadera/sanidad-animal/enfermedades/rabia/Rabia.aspx

- Villalbí JR, Cleries M, Bouis S, Peracho V, Duran J, Casas C. Decline in hospitalisations due to dog bite injuries in Catalonia, 1997-2008. An effect of government regulation? Inj Prev. 2010;16:408-10.

- Shen J, Rouse J, Godbole M, Wells HL, Boppana S, Schwebel DC. Systematic Review: Interventions to Educate Children about Dog Safety and Prevent Pediatric Dog-Bite Injuries: A Meta-Analytic Review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:779-91.

- Dixon CA, Mahabee-Gittens EM, Hart KW, Lindsell CJ. Dog bite prevention: An assessment of child knowledge. J Pediatr. 2012;160:337-341.e2.