Vol. 23 - Num. 91

Original Papers

Pediatric palliative care situation in Primary Care

Lucía Morán Roldána, Cristina García-Mauriño Alcázarb

aPediatra. CS San Fermín. Madrid. España.

bPediatra. The Institute of Global Health. Kensington. Londres. Reino Unido.

Correspondence: L Morán. E-mail: lucmoran@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Morán Roldán L, García-Mauriño Alcázar C. Pediatric palliative care situation in Primary Care. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2021;23:261-72.

Published in Internet: 10-09-2021 - Visits: 12152

Abstract

Introduction: primary care (PC) paediatricians are an essential pillar in the management of children with palliative care (PPC) needs. The aim of this study was to perform a descriptive analysis of the situation of these professionals in Madrid.

Material and methods: we conducted a cross-sectional study. Questionnaires were designed, pilot-tested and disseminated electronically using a mailing list that includes active PC paediatricians practicing in Madrid.

Results: we obtained 199 responses to the survey. Most respondents (97%) identified the correct definition of patients with palliative care needs. Only 24.6% reported managing some of these patients in their regular practice. Respondents thought cancer patients were the largest subset of patients with palliative care needs, and almost half believed there were paediatric palliative care units (PPCUs) in hospitals that did not have one. Most respondents (70.8%) had never received specific training on palliative care. More than half did not feel integrated in palliative care teams, and no more than 35% reported interaction between the PC and PPC teams. Only 14% felt adequately trained to manage these children, while 99% expressed a desire to be involved in their management and followup.

Conclusions: there are significant lacks and limitations for PC paediatricians as regards palliative care. Deficient training and a lack of communication between care levels were the main problems identified by respondents. Specific training programmes need to be implemented along with promotion of shared care.

Keywords

● Health care needs and demands ● Palliative care ● Primary careINTRODUCTION

Primary care (PC) is defined as health care focused on the needs and circumstances of individuals, families and communities, encompassing physical, psychological and social health and wellbeing.

This entails a comprehensive approach ranging from health promotion and prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care in order to meet the health care needs of the individual through the lifespan.1

All of the above, together with the values and attitudes of health providers working in this field, justify PC and make it an indispensable pillar in the care of patients with complex chronic disease and patients that require palliative care.

At this point, it would be useful to clarify concepts in the context of paediatric care. We use the term patients with complex chronic disease (CCD) to refer to patients with chronic disease that is known or unknown but suspected, severe or associated with medical fragility, with significant functional limitation, in many cases dependent on technology and who have substantial health care needs and pose a significant burden to the family.2

We use the term paediatric palliative care (PPC) to refer to the care and services provided to patients with advanced, incurable and irreversible disease that results in extreme fragility and is life-threatening and limiting, with the main goals of improving the quality of life of patients and their families and alleviate suffering.

Despite the conceptual differences between primary and palliative care, both are characterised by an integral approach to patients and families in response to their physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs and problems.

Another motivation for our study was the increase in the official documents both at the national and international level that highlight the importance of involving PC providers in palliative care delivery and PC paediatricians in the delivery of PPC, considering the latter another competency included in their scope of practice and underscoring the need of providing specific training on PPC to providers.3-7

Paediatrics associations (Asociación Española de Pediatría, Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria, Asociación Madrileña de Pediatría de Atención Primaria) have also been making statements regarding the need to involve PC paediatricians in the care of patients with palliative care needs with increasing frequency.8-11

A review of the literature on the management of patients with CCD and palliative care needs by PC teams showed that there are numerous recent studies on the subject in the adult population.12-16 However, and despite the fact that it is estimated that each year there are between 5500 and 7500 patients aged 0 to 19 years that need palliative care in Spain17(a number that will be increasing thanks to medical advances, improvements in care, greater awareness, growing support networks etc.), there are hardly any studies that provide updated data on the involvement of paediatricians in the care of these patients18,19 (contrary to the international medical literature in recent years, in which the role of PC paediatricians in the delivery of palliative care is growing in importance20-22).

Thus, due to the clear need for the participation of PC paediatricians in palliative care, the exponential increase of this type of patient and the lack of published evidence on the shifting reality of paediatric palliative care in the PC setting, we believed our study would be relevant.

The primary objective of the study was to analyse the current overall situation of paediatric palliative care in the PC setting in the Community of Madrid (CM) from the perspective of the providers.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional, observational and descriptive study.

Study universe

The study universe consisted of all physicians (without distinction between paediatricians and family physicians) that provided PC paediatric care in the Community of Madrid, Spain, at the time of recruitment.

Due to the lack of updated official data, we took as reference the last official figure published in the PC Administration report available through the institutional intranet from December 2017, according to which there were 911 filled primary care paediatrician positions in the Community of Madrid.

Sampling and sample size

We reached out to the population of interest mainly through the corporate mailing list of the Asociación Madrileña de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Primary Care Paediatrics Association of Madrid), which includes the members of the association that chose to be added to it (a total of 742 providers). We also sought participants through the contacts of the providers that had received the questionnaire through WhatsApp groups, email etc.

We recruited participants by non-probability consecutive sampling. The survey included clinicians that met the criteria defining the population under study and who submitted correctly completed responses by the established deadline.

Data collection

To collect data, we developed a questionnaire that has not been validated but pilot tested previously by paediatricians (Table 1). The questionnaire was self-administered on an anonymous basis by clinicians between June 1 and 15, 2019.

| Table 1. Survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| 1. Sex | ||||

| 2. Age | ||||

| 3. Years of experience as primary care paediatrician | ||||

| 4. Current workplace (name of primary care centre) | ||||

| 5. Approximate number of children in your caseload | ||||

| Knowledge and training on paediatric palliative care | ||||

| 6. Which answer provides the best definition of a paediatric patient with palliative care needs? | ||||

| 7. Which do you think is the group of patients managed most frequently by paediatric palliative care units? | ||||

| 8. Which hospitals in the Community of Madrid have a paediatric palliative care unit? (you can check more than one option) | ||||

| 9. Have you attended a training or conference on paediatric palliative care in the past 5 years? | ||||

| 10. If you answered no to the previous question: which, among others, have been the reasons? (you can check more than one option) | ||||

| Paediatric palliative care in your everyday clinical practice | ||||

| 11. In your caseload: can you think of any patient that has palliative care needs? | ||||

| 12. If you do: do you consider yourself the clinician in charge of any of these patients? (meaning the clinician responsible for the comprehensive care of the child and family, whether or not the child is being followed up by other specialists) | ||||

| 13. If you answered yes to question 11: do you know if any of these patients receives care from a paediatric intensive care unit? | ||||

| 14. In your career as a primary care paediatrician in the Community of Madrid, have you ever taken the initiative to contact the paediatric palliative care unit to improve the management of a patient? | ||||

| 15. In your career as a primary care paediatrician in the Community of Madrid, have you ever been contacted by the paediatric palliative care unit to share and coordinate the management of a patient/family with palliative care needs? | ||||

| 16. In your career as a primary care paediatrician in the Community of Madrid, have you ever made home visits to care for a patient with complex chronic disease or palliative care needs? | ||||

| 17. If you answered no to the previous question: which are the main reasons for it? | ||||

| Self-reflection and personal opinions | ||||

| 18. Do you believe that children with palliative care needs and their families are currently receiving adequate care in the Community of Madrid? | ||||

| 19. Do you think that specialised paediatric palliative care units integrate PC paediatricians in the care team that manages these patients? | ||||

| 20. How do you think the care of paediatric patients with palliative care needs should be organised? | ||||

| 21. Given your current training and experience, do you currently feel competent to manage patients with complex chronic disease or with palliative care needs in your practice? | ||||

| 22. What about patients with a tracheostomy or requiring home mechanical ventilation? | ||||

| 23. What about patients with gastrostomy and requiring enteral nutrition? | ||||

| 24. And what about prescribing opioids to paediatric patients? | ||||

| 25. What do you view as essential for the purpose of managing these patients adequately in your primary care clinic? | ||||

| 26. Overall, provided changes are made to the organization of care delivery, continuing education improved and direct support is available from specialised paediatric palliative care teams, would you like and would you be willing to care for patients with palliative care needs in the clinic or at home? | ||||

The questionnaire included questions on demographic characteristics, knowledge and basic training on PPC, involvement in PPC and regular activity of the clinician related to PPC and identified problems in the delivery of PPC from the PC setting.

The questionnaire was developed by the principal investigator based on questionnaires used in previous studies.19,23

Once the final version of the questionnaire was ready, it was converted to the Google Docs format for dissemination.

Statistical analysis

We entered the data collected through Google Docs in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, after which we used the Stata software to calculate percentage distributions for the qualitative and quantitative variables under study. We also calculated measures of central tendency and dispersion.

RESULTS

We received a total of 199 questionnaires.

Profile of PC paediatricians

Of all respondents, 84.8% were female, and the greatest proportions of the sample corresponded to clinicians aged more than 50 years (48.2%) and with more experience (59.3% with 15 years or more) (Fig. 1). Most respondents (60.3%) had caseloads of 1000-1500 patients.

| Figure 1. Demographic characteristics of surveyed clinicians (percent [%] distribution of PC paediatricians by age group and years of experience in PC) |

|---|

![Figure 1. Demographic characteristics of surveyed clinicians (percent [%] distribution of PC paediatricians by age group and years of experience in PC)](/files/1117-4696-fichero/rpap_1798_paliativos_ap_figura_1_EN.jpg) |

Knowledge and training in PPC

All respondents reported the subjective perception that they understood the meaning of “patient with palliative care needs”, and nearly all (97%, 195/199) identified the correct definition for the term.

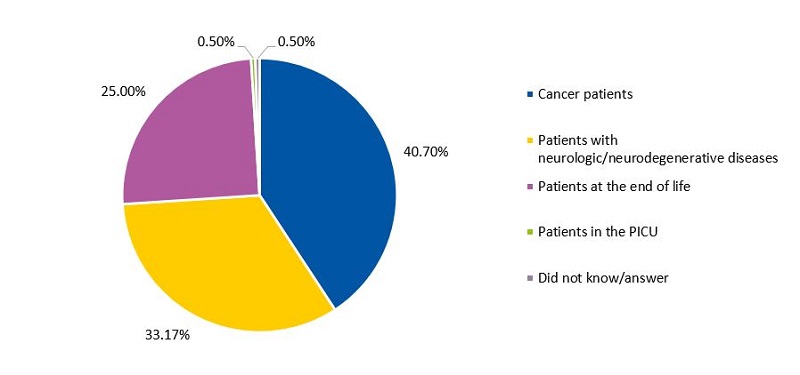

To the question of which patients are most frequently managed in specialised PPC units (PPCUs), 40.7% of respondents answered cancer patients (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2. Percent distribution (in decreasing order) of PC paediatricians by the group of patients they believed constituted the majority of patients managed in specialised PPCUs |

|---|

|

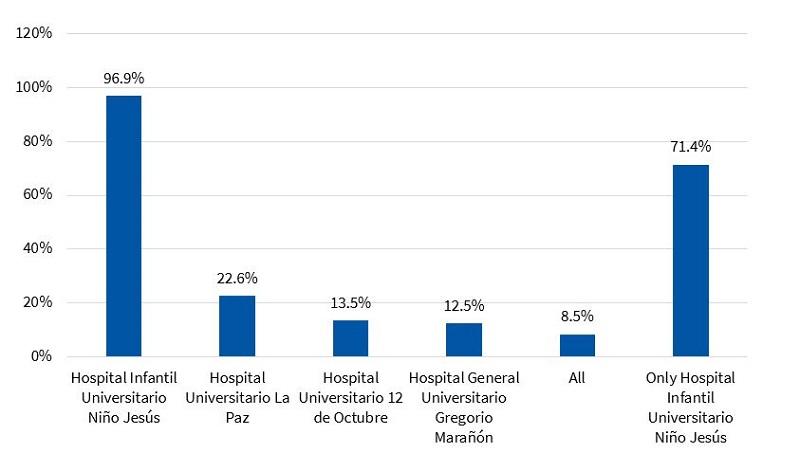

When it came to the hospitals in the Community of Madrid that have PPCUs, nearly all respondents (96.9%) identified the Hospital Universitario Niño Jesús (HNJ) as one of them. Of the subset that stated the HNJ had a PPCU, 26.4% (51/193) believed that there were additional PPCUs in other hospitals (the most frequent combination was the HNJ and the Hospital Infantil Universitario La Paz: 17 respondents).

We ought to highlight that 97 respondents (48.7%) answered that there were PPCUs in hospitals other than the HNJ (in different combinations) and 17 paediatricians (8.5%) answered that every tertiary care hospital in the Community of Madrid had a PPCU (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3. Percentage of PC paediatricians (over the total sample) that believed the given hospital in the Community of Madrid had a specialised PPCU |

|---|

|

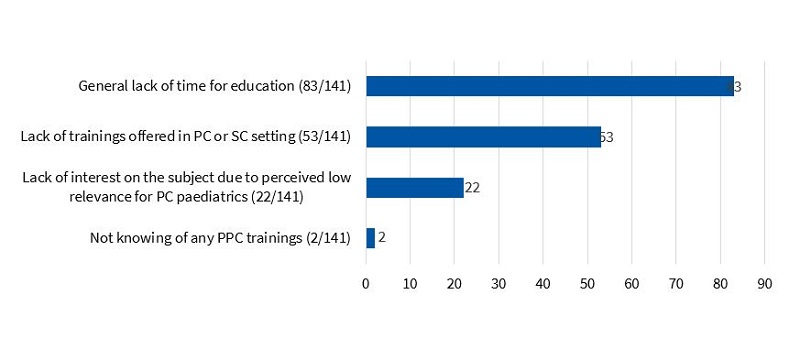

Of all participants, 70.8% (141/199) reported that they had never attended any trainings or conferences on PPC in the past 5 years. The reasons cited most frequently were lack of time for education (58.8%) and lack of training programmes offered in PC or speciality care (SC) settings (37.5%) (Fig. 4). The proportion of paediatricians that had attended trainings or conferences of PPC was highest in the group aged more than 50 years (44.8%; p = 0.008),

| Figure 4. Main reasons for not having been trained on PPC identified by clinicians (expressed as absolute frequency distribution) |

|---|

|

Integration and presence of palliative care in the clinical practice of PC paediatricians

Only 24.6% (49/199) of clinicians could think of a child in their caseloads with palliative care needs; 46 of them identified between 1 and 3 such patients, which would correspond to an estimated total of children managed in PC with palliative care needs of 46 (minimum) to 138 (maximum). Only 3 paediatricians identified more than 3 patients in their caseloads eligible for palliative care. We ought to mention that 6 clinicians acknowledged that they would not know how to recognise these patients.

Of all the paediatricians that had patients receiving PPC (n = 49), 40% reported feeling that they were not the physician in charge of the patient.

Connection between PC paediatricians and PPCUs

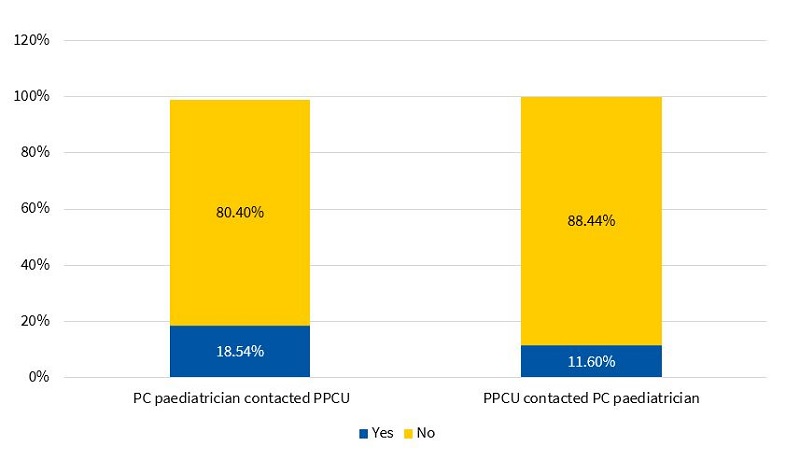

To the question whether they had ever contacted a PPCU regarding the management of a paediatric patient at the PC level, only 18.5% (37/199) answered that they had. Also, 11.6% (22/199) reported having been contacted by a PPCU (Fig. 5).

| Figure 5. Percentage of primary care paediatricians out of the total surveyed (N = 199) that reported having contact with a PPCU (the first column reflects contact initiated by the PC paediatrician and the second contact initiated by the PPCU) |

|---|

|

Of the 49 paediatricians that could identify patients with palliative care needs in their caseloads, 34.6% reported having taken the initiative to contact the PPCU (17/49, Fisher: 0.007), and 22.4% (11/49, Fisher: 0.02) having been contacted by the PPCU first. Twenty-one paediatricians (42%) reported having no contact at all the PPCU (including 6 that acknowledged not knowing whether their patients did or did not receive palliative care of any kind).

Home health care

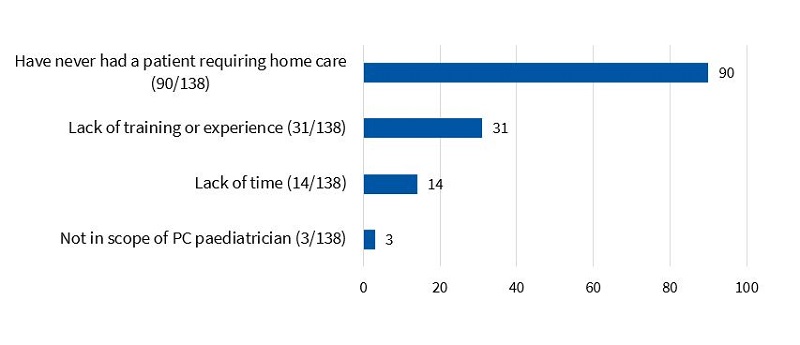

Only 30.6% of respondents (61/199) had provided home care for management of patients with CCD or with palliative care needs (at any point in their careers as PC paediatricians). In the group of respondents that reported not doing home visits (138/199), the most frequent reasons given for not providing home care, excluding not having any patients with these needs (90/138), were lack of training and experience (22.4%) and lack of time specifically allocated to home care (10.4%) (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6. Reasons identified by PC paediatricians for not providing home care to paediatric patients with palliative care needs (absolute frequency of each answer in the group of paediatricians that did not do home visits) |

|---|

|

Perceptions regarding palliative care and self-competence

More than half of PC paediatricians (557%, 111/199) expressed not feeling integrated with PPCUs in the Community of Madrid.

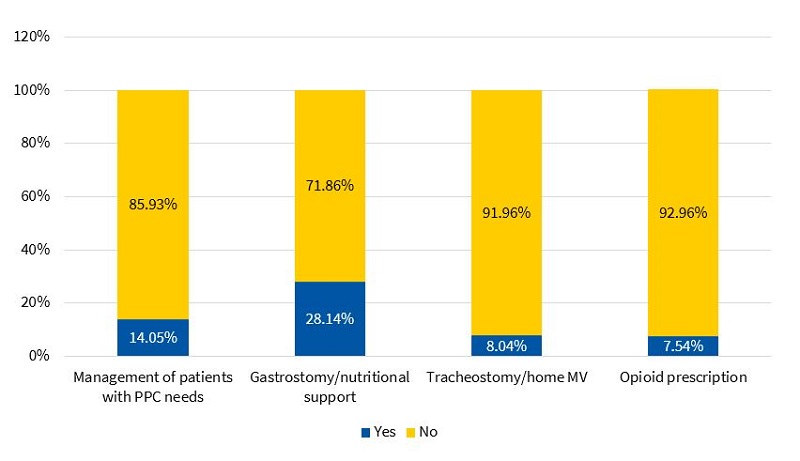

Similarly, in self-reflection, only 14% expressed feeling competent and/or confident to manage these patients appropriately (with higher proportions of clinicians with less than 5 and more than 15 years of experience reporting feeling confident: 42.8% and 46.4%, respectively).

In addition, 28.1% of respondents (56/199) reported adequate skills to manage gastrostomies and enteral nutrition. In contrast, only 15 paediatricians (8%) reported feeling confident managing tracheostomies and at-home mechanical ventilation. Another salient finding was that only 15 (7.5%) felt competent in the prescription of opioids (Fig. 7).

| Figure 7. Percentage of PC paediatricians that expressed feeling confident (yes/no answer) in the management of patients with PPC needs and the specified care interventions |

|---|

|

Notwithstanding, most PC paediatricians perceived the management of patients with palliative care needs positively (only 34 of the 199 paediatricians perceived that these patients were not managed correctly).

Needs, problems and barriers identified by PC paediatricians

Nearly all respondents thought that these patients required more comprehensive and better integrated care, with PC paediatricians and speciality clinicians in PPCU sharing the responsibility and management of the patients (99.5%).

Furthermore, 91.9% expressed a willingness to manage these patients in the clinic setting or at home.

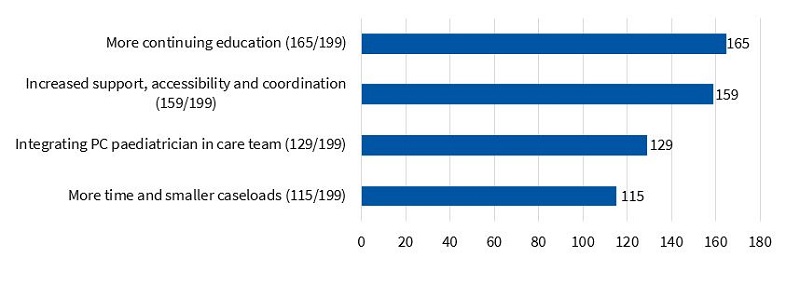

To be able to do so, most respondents (165/199, 83%) considered that more continuing education on palliative care needed to be offered at the PC and SC levels. Also, a substantial number of respondents (155/199, 77.8%) declared that they needed more support from PPCUs, increased access to them and more coordination between the two care settings to improve the management of these patients (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8. Needs identified by PC paediatricians to improve the management of patients with PPC needs (expressed as absolute frequency of the answers) |

|---|

|

DISCUSSION

Primary care paediatricians are an essential and indispensable component in the care and management of children with palliative care needs, and they constitute the most basic level of care that is most accessible to the population.

Although the literature that underscores the importance of their involvement is growing in volume, there are still many and important improvements that need to occur before this objective is achieved.

The analysis of the obtained data showed that PC paediatricians seemed to be quite familiar with the concept of the paediatric patient with PPC needs, which could have a positive impact on the ability to identify these patients.

However, the data did not support this hypothesis, as it once again evinced the difficulty of identifying these patients. If we estimate the prevalence of patients eligible for PPC in the Community of Madrid based on the prevalence published by the European Association for Palliative Care in 201717 (10 to 16 children and youth under 20 years with palliative care needs per 100 000 inhabitants under 20 years) and the last population census of 2016, there would be a total of 1316 to 2105 patients with palliative care needs in this age range.

To this figure, we must add the important datum of the number of patients included each year in the PPC of the HNJ, which amounts to 300 (count provided by the unit).

Both results are substantially different from the values obtained in our study, in which a maximum of 138 children with PPC needs were identified.

Despite these differences, we ought to highlight that a negligible proportion of respondents reported not knowing how to identify these patients, when the actual proportion is probably larger.

We found that PC paediatricians continue to have inaccurate perceptions of PPC. Respondents considered cancer patients the largest group of patients in PPC services, when in fact they only amount to 30% of the total.17 Most patients included in these programmes are not cancer patients, but rather patients with neurological disorders (up to 70%17), including neurodegenerative, metabolic and genetic diseases and polymalformative genetic syndromes.

Furthermore, a high percentage of clinicians continued to believe that there are PPCUs in hospitals that do not have these services (the frequent combination of the HNJ and Hospital La Paz is probably due to confusing the CCD unit in the latter hospital with a PPCU). Nevertheless, we ought to note that when we compared the data obtained in our study with the data obtained in the study conducted in Madrid in 2010,18 we found a significant increase in the number of PC paediatricians that knew about the PPCU of the HNJ from only 35% to 96.9% of paediatricians.

One of the salient unfavourable findings of the study concerned the deficient communication and collaboration between PC and SC paediatric management teams described by respondents.

In this regard, many paediatricians (slightly more than 50%) expressed feeling a lack of integration with PPCUs. Contact between these 2 levels of care to share the management of these patients was very scarce (contact was more frequent in the subset of paediatricians that identified patients with PPC needs in their caseloads, but it did not exceed 35% of clinicians in any case).

In our survey, most respondents reported not feeling competent or confident and not having sufficient resources to care for these patients.

Another finding that we should highlight and that was consistent with the results of the 2018 study19 was the low proportion of paediatricians that felt confident and had basic skills to manage tracheostomies and mechanical ventilation in the patient’s home. We also found a generalised lack of experience in opioid prescription (respondents familiar with it amounted to less than 15% of the total). On the other hand, the limited experience delivering home care is probably related to the infrequent familiarity with technologies and devices such as tracheostomies, ventilators or enteral feeding tubes, which should be within the scope of practice of these professionals (as demonstrated by several studies in adults).

What was clear and would largely explain the significant limitations of PC paediatricians revealed through questionnaire items and the statements of participants is that there is a lack of training in PPC (with the proportion of clinicians that had not had any even exceeding the proportion found in previous studies18,19).

This situation may reflect a perception by paediatricians that they do not need to contribute significantly to the care of these children, as most believed that these patients were being adequately managed (independently of their own participation in their management).

However, this contrasts with their desire to learn and get involved in the care of patients with palliative care needs, which unquestionably requires training on the subject. This would allow paediatricians to acquire the necessary skills to identify patients eligible for palliative care, collaborate in care delivery and clinical decision-making and improve their integration in multidisciplinary teams.

This objective requires the commitment of paediatricians as well as speciality care teams and health care administrators to guarantee and boost learning, facilitate ready and close collaboration between levels of care and help develop a high-quality care pathway.

All of the above would achieve more holistic, integrated and coordinated delivery of multidisciplinary care, improving the quality of life of children and their families.

CONCLUSION

Paediatric palliative care is characterised by a comprehensive, integral, multimodal and multidisciplinary approach to the management of patients and families in which primary care providers must participate actively to achieve a common goal: improving the wellbeing and quality of life of children and their families.

The PC paediatricians currently practicing in the Community of Madrid exhibited significant deficiencies and limitations for the purpose of contributing appropriately to delivering quality care to patients with PPC needs.

Although these clinicians have grown more aware of the need of PPC, they continued to evince the dearth of education received on the subject of palliative care and the persistence of misconceptions about this field. They also exhibited a limited capacity in recognising these patients and limited skills to manage these patients adequately.

Most PC paediatricians did not identify any patients with palliative care needs in their caseloads, which was at odds with the literature and the records of facilities offering specialised care, which report a growing number of patients in these programmes. It is worth noting that despite this, respondents that could identify patients with these needs reported a heterogeneous level of involvement and responsibility in the management of these patients.

Primary care paediatricians reported low involvement in PPC programmes managed by PPCUs. Responses also evinced a reciprocal lack of communication between these 2 levels of care. However, although it may appear contradictory, respondents perceived the quality of the care provided to patients by PPCUs as good.

A salient finding of the study was that PC paediatricians expressed a desire to be involved in the care of these patients and identified key opportunities for improvement in order to provide better care, chief of which were more education on the subject, greater involvement of PC paediatricians in PPC programmes, more support from and accessibility to PPCUs and more time to devote to the management of these patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

CCD: complex chronic disease · CM: Community of Madrid · HNJ: Hospital Universitario Niño Jesús · PC: Primary Care · PPC: paediatric palliative care · PPCU: paediatric palliative care unit· SC: speciality care.

REFERENCES

- Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. 67th World Health Assembly, May 24, 2014. In: World Health Organization [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-sp.pdf

- Benítez del Rosario MA, Asensio Fraile A. Fundamentos y objetivos de los cuidados paliativos. Aten Primaria. 2002;29:50-2.

- Steering Committee of the EAPC, Task Force on Palliative Care for Children and Adolescents. IMPaCCT: estándares para cuidados paliativos pediátricos en Europa. Med Pal (Madrid). 2008;15:175-80.

- Ley 16/2003, de 28 de mayo, de cohesión y calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud. BOE no. 128 of 29 January, 2003. In: BOE [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2003-10715

- Real Decreto 1030/2006, de 15 de septiembre, por el que se establece la cartera de servicios comunes del Sistema Nacional de Salud y el procedimiento para su actualización. BOE no. 222 of 16 September, 2006. In: BOE [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2006-16212

- Estrategia en Cuidados Paliativos del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Actualización 2010-2014. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/docs/paliativos/cuidadospaliativos.pdf

- Cuidados paliativos pediátricos en el Sistema Nacional de Salud: criterios de atención. In: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/01-Cuidados_Paliativos_Pediatricos_SNS.pdf

- Aparicio Rodrigo M, Arana Navarro T, Bras i Marquillas J, Callejas Pozo JE, Kóvacs A, Kubátová G, et al. Currículum de formación en Pediatría de Atención Primaria. In: AEPap [online] [accessed 01/09/2021]. Available at www.aepap.org/sites/default/files/documento/archivos-adjuntos/curriculo_europeo_traducido.pdf

- Santos Herráiz P, Losa Frías V, Labarga BH. Cuidados paliativos en Pediatría. Form Act Pediatr Aten Prim. 2017;10:109-14.

- Quiroga Cantero E. Cuidados paliativos: qué debe saber un pediatra de Atención Primaria. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2014;(23):45-8.

- Ortiz San Román L, Martino Alba RJ. Enfoque paliativo en Pediatría. Pediatr Integral. 2016;XX(2):131.e1-131.e7.

- Blay C, Martori JC, Limon E, Oller R, Vila L, Gómez-Batiste X. Busca tu 1%: prevalencia y mortalidad de una cohorte comunitaria de personas con enfermedad crónica avanzada y necesidades paliativas. Aten Primaria. 2019;51:71-9.

- Herrera Molina E, Rocafort Gil J, Cuervo Pinna MÁ, Redondo Moralo MJ. Primer nivel asistencial en cuidados paliativos: evolución del contenido de la cartera de servicios de Atención Primaria y criterios de derivación al nivel de soporte. Aten Primaria. 2006;38:85-8.

- Vega T, Arrieta E, Lozano JE, Miralles M, Anes Y, Gómez C, et al. Atención sanitaria paliativa y de soporte de los equipos de Atención Primaria en el domicilio. Gac Sanit. 2011;25:205-10.

- Rocafort Gil J, Herrera Molina E, Fernández Bermejo F, Grajera Paredes María ME, Redondo Moralo MJ, Díaz Díez F, et al. Equipos de soporte de cuidados paliativos y dedicación de los equipos de Atención Primaria a pacientes en situación terminal en sus domicilios. Aten Primaria. 2006;38:316-23.

- Meléndez Gracia A. Cuidados Paliativos en AP. ¿Sola, soportada o sustituida? AMF. 2014;10:241-2..

- Cochrane H, Liyanage S, Nantambi R. Palliative Care Statistics for Children and Young Adults. Health and Care Partnerships Analysis. London: Department of Health, 2007.

- Astray San Martín A. Encuesta sobre cuidados paliativos a pediatras de Atención Primaria en un área sanitaria de Madrid. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2010;12:33-40.

- Caballero Pérez V, Rigal Andrés M, Beltrán García S, Parra Plantagenet-Whyte F, Moliner Robredo MC, Gracia Torralba L, et al. Influencia de los recursos especializados en cuidados paliativos pediátricos en los pediatras de Atención Primaria. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2018;20:133-42.

- Jünger S, Vedeer AE, Milde S, Fischbach T, Zernikow B, Radbruch L. Paediatric palliative home care by general paediatricians: a multimethod study on perceived barriers and incentives. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9:11.

- Foster CC, Mangione-Smith R, Simon TD. Caring for Children with Medical Complexity: Perspectives of Primary Care Providers. J Pediatr. 2017;182:275-282.e4.

- Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schepers SA, Schouten-Van Meeteren AYN, Grootenhuis MA, Van Delden JJM. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a paediatric palliative care team. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1).

- Calleja Gero ML, Rus Palacios M, Martino Alba R, Monleón Luque M, Conejo Moreno D, Ruiz-Falcó Rojas ML. Cuestionario sobre cuidados paliativos a neuropediatras. Neurologia. 2012;27:277-8.