Influence of nationality on the prevalence of frequent diseases in Primary Health Care

Inmaculada Navarro Féleza, Lourdes Martínez Angulob, Milagros Gascó Eguiluzc, Cristina Coy Vidald, Margarita García Canelae, Celia Tajada Vitalesf, José Antonio de la Fuente Cadenasg

aEnfermera. EAP Santa Coloma de Gramenet 6. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España .

bEnfermera. EAP Santa Coloma de Gramenet 1. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

cPediatra. EAP Santa Coloma de Gramenet 6. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

dOdontóloga. EAP Badalona 5. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

eTrabajadora social. Dirección de Atención Primaria Barcelona Ciudad. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

fMédico de Familia. EAP Santa Coloma de Gramenet 1. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

gMédico de Familia. Servicio de Atención Primaria Barcelonés Nord i Maresme. Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS). Barcelona. España.

Correspondence: JA de la Fuente . E-mail: jadelafuente.bnm.ics@gencat.cat

Reference of this article: Navarro Félez I, Martínez Angulo L, Gascó Eguiluz M, Coy Vidal C, García Canela M, Tajada Vitales C, et al. Influence of nationality on the prevalence of frequent diseases in Primary Health Care. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2020;22:e1-e11.

Published in Internet: 18-02-2020 - Visits: 14890

Abstract

Introduction: prevalence of certain diseases varies depending on socioeconomic and cultural factors. The aim of our study was to describe the documented frequency of excess weight, dental caries, iron-deficiency anaemia (IDA) and atopic dermatitis (AD) in the local paediatric population by country of origin, and to assess whether there were differences based on national origin.

Material and methods: we conducted a descriptive study of the diagnoses recorded in the primary care health records database. We analysed age, sex, nationality and socioeconomic status.

Results: The population under study consisted of 81 541 children aged 0 to 14 years. The majority were Spanish (84.1%), followed in frequency by children from Northwest Africa (6.9%) and children from India and Pakistan (3%). The prevalence of excess weight was 14.2%, with no differences between the Spanish and the immigrant population with the exception of a higher prevalence in children of Latin American descent (22.47%). The overall prevalence of caries was 17.8%, with significant differences between the Spanish population and children from other regions (15.13% vs. 28.4%). The prevalence of IDA was 0.75%, and we found differences based on country of origin, with a 10-fold prevalence of IDA in children of Indian or Pakistani descent (5.4%). The overall prevalence of AD was 15.46%, with differences based on national origin; AD was significantly more frequent in children of Chinese (20.46%) and Northwest African (18.58%) descent.

Conclusions: We found considerable differences in the prevalence of the diseases under study based on the country of origin of the child. The primary care system should implement preventive strategies adapted to the multicultural populations served by our primary care centres.

Keywords

● Atopic eczema ● Dental caries ● Epidemiology ● Immigration ● Iron deficiency anemia ● OverweightINTRODUCTION

Multiculturalism and immigration present significant challenges to health care professionals.

Despite the economic crisis, Spain (and especially Catalonia) continues to receive individuals and families that seek better living conditions, although immigration has declined in recent years. In 2016, immigrants amounted to 13.6% of the population of Catalonia and 13.94% of the population aged 0 to 14 years in this region (data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística [National Institute of Statistics, INE]).

A population of individuals of diverse origins is a heterogeneous collective.1,2 On the other hand, we must keep in mind that the autochthonous population is also heterogeneous. Health care systems must strive to offer the same quality of care to every user, independently of membership in one or another cultural group.3

Health care problems in the immigrant population are not essentially different from those in the native Spanish population once we exclude imported diseases.3 The main sources of health inequality in the immigrant population are low socioeconomic status, an irregular legal status and substandard housing conditions.4,5 This is not to say that certain cultural factors may not have an influence on the increased prevalence of specific diseases.

Diet is influenced by cultural background, religious beliefs and socioeconomic status.6,7 A family diet that stays close to the usual diet in the country of origin may have a protective effect against obesity.7,8 The process of cultural integration usually leads to changes in the dietary habits of the paediatric population, with an increase in the consumption of processed foods, which can increase the risk of obesity.6,8,9

The prevalence of obesity varies between studies based on the criteria applied to its definition.10 At present, there are 3 widely used standards applied to the diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children: the growth reference of the World Health Organization (WHO),11 the standard definitions of the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)12 and the growth tables of Orbegozo for the Spanish population.13 The lowest proportions of excess weight are found applying the growth tables for the Spanish population (26.4%)14 and the highest applying the growth reference of the WHO (41.3%)15.

There is variability in the published literature in the factors found to be associated with excess weight in children. It is generally found to be associated with male sex,15-17 low socioeconomic status15-17 and low parental educational attainment.15,18,20 Some studies have found an association between migrant status or background and an increased prevalence of obesity,8,17,19,20 but others have not confirmed it.15,17

The 2015 ALADINO study in the Spanish population15 found a 23.2% prevalence of overweight and a 18.1% prevalence of obesity applying the WHO growth reference. The prevalence of overweight is similar in boys and girls, but obesity is more prevalent in boys. Orsola et al.19 found a slight increase in the prevalence of obesity in the population of immigrant children, especially those of South American descent. The POIBA project17 in Barcelona found a 24.0% prevalence of overweight and a 12.7% prevalence of obesity, with a higher prevalence of obesity in boys.

Escartín et al.20 found a significantly higher prevalence of obesity and of overweight in the immigrant population compared to the native Spanish population (39.4% vs. 28.9%) in children aged 6 years; these differences remained after adjusting the analysis for socioeconomic status, parental educational attainment, smoking and weight gain during pregnancy. One systematic review18 found that the prevalence of childhood obesity was associated with parental educational attainment and sex, but found no differences based on region of origin.

Dental caries is currently the most prevalent chronic disease in the paediatric population.21 Its aetiology is multifactorial and related to insufficient or inadequate oral hygiene habits,21-23 night-time feeding (especially in infants),24 a high sugar intake24,25 and low parental socioeconomic status.17,24-26 Nearly all studies conducted in Spain have found a higher prevalence of dental caries in the immigrant population,25-28 including the Oral Health Survey of Spain of 2015.25

A study by Barriuso et al.29 and the Oral Health Survey of Spain25 found that oral hygiene habits in the Spanish population are far from meeting current recommendations. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that restorative approaches have not succeeded in the objective of reducing the development of caries.30-31

Iron-deficiency anaemia (IDA) is a significant problem in children in many countries.32 In Spain, IDA is frequent in immigrant children (10%).2 The segments of the population most affected by IDA are infants and toddlers (6-24 months) and women of reproductive age.2 A study by Sánchez et al.33 in children aged less than 6 years found a higher proportion of iron deficiency and IDA in immigrant subpopulations with the exception of those from Central America. Saunders et al.34 did not find significant differences in the prevalence of IDA based on maternal country of origin.

Primary care providers have found a higher frequency of visits for atopic dermatitis (AD) in children of immigrant origin. In several studies conducted in speciality clinics, AD is one of the most frequent reasons for seeking care.35,36 Cantarutti et al.37 reviewed visits due to skin problems in paediatric primary care practices and found that the incidence and prevalence of AD increased between 2006 and 2012, and that AD was the most frequent reason for visits to the dermatologist.

Pérez-Crespo et al.38 found that atopic dermatitis was more frequent in the immigrant population in a dermatology clinic (odds ratio [OR]: 1.65; 95% confidence interval [95 CI]: 1.19-2.31). Other studies39,40 have found that AD is the most frequent reason for dermatology visits in immigrant children, but found no differences relative to the native population.

We conducted a study to identify potential differences in the prevalence of a collection of diseases frequently found in paediatrics practice based on the country of origin of the patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analysed data for all children aged 0 to 14 years in the primary care catchment population of the Barcelonés Norte and Maresme primary care centres of the Catalonian public health system (Institut Català de la Salut, ICS). We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study.

We collected data from the electronic primary care health records database (eCAP).

The dependent variables were the presence of specific diseases defined as:

- Excess weight: any child with a corresponding ICD 10 code (E66: obesity or R63.5: overweight) or with a body mass index (BMI) corresponding to obesity or overweight based on the Orbegozo growth tables.13 We excluded from the analysis children whose records lacked documentation of the BMI or a diagnostic code.

- Dental caries: defined as documentation of diagnostic code K02 (caries) or of CAOD index ≥1 or a COD index ≥1. If there was no such documentation, we considered the child to be caries-free.

- Iron-deficiency anaemia: code D50.

- Atopic dermatitis: code L20.

The independent variables under study were age, sex, country of origin and socioeconomic status. We grouped children by age in 2 groups: 0 to 5 years and 6 to 14 years.

For the purpose of the study, we considered the country of origin was the one recorded in the nationality field of the eCAP database, and we grouped countries into the following categories: Spain, Northwest Africa; India-Pakistan; China-Southeast Asia; Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Western Europe and other.

We were not able to determine socioeconomic status (SES) for each individual. We used the socioeconomic status estimated by the Department of Health of the Government of Catalonia.42 We created 2 SES groups: very low SES and low-middle-high SES.

We carried out a descriptive analysis of the data, comparing the prevalence of diseases between the different nationality groups by means of the chi square test for qualitative variables, calculating the 95 CI.

We collected anonymised data from the centralised database and did not obtain any personally identifiable information. The study adhered to good clinical practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Committee of Ethics and Clinical Research of the Institut d’Investigació en Atenció Primària (IDIAP) Jordi Gol, the body overseeing research in primary care settings of the ICS (project file P18/066).

RESULTS

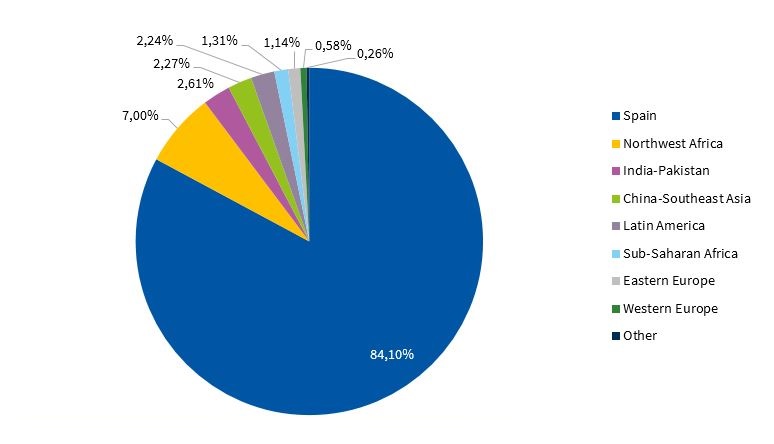

The sample included a total of 81 541 children. The most frequent country of origin was Spain (84.1%), followed in frequency by the Northwest Africa group and the India-Pakistan group (Fig. 1).

Of this total, 48.3% were girls. The mean age was 7.48 years (95 CI: 7.45-7.51). The age was slightly older in the Latin American group compared to the Spanish group, while children in the India-Pakistan and Northwest Africa group were younger.

The overall prevalence of excess weight was 14.2%. When we compared native Spanish children with children from all other countries combined, we did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of excess weight : 14.1 versus 14.7% (p = .120). The prevalence was higher in children older than 5 years compared to younger children: 15.6 versus 11.3% (p < .000). Table 1 presents the distribution of excess weight by country of origin and age group. We found that the prevalence of excess weight was higher in Latin American children in both age groups.

| Table 1. Prevalence of excess weight by country of origin and age group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total children | Age 0-5 years | Age 6-14 years | |||||||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | ||||

| Spain | 14.12% | 13.84% | 14.41% | 10.69% | 10.24% | 11.13% | 15.73% | 15.37% | 16.09% |

| Northwest Africa | 12.29% | 11.28% | 13.29% | 14.21% | 12.49% | 15.94% | 11.08% | 9.85% | 12.31% |

| India-Pakistan | 14.49% | 12.88% | 16.09% | 12.30% | 9.84% | 14.76% | 15.76% | 13.67% | 17.84% |

| China-Southeast Asia | 14.32% | 12.54% | 16.10% | 11.90% | 8.86% | 14.94% | 15.33% | 13.15% | 17.51% |

| Latin America | 22.47% | 20.36% | 24.58% | 21.45% | 17.56% | 25.33% | 22.88% | 20.37% | 25.39% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 15.42% | 13.12% | 17.72% | 14.95% | 10.92% | 18.98% | 15.63% | 12.83% | 18.44% |

| Eastern Europe | 13.57% | 11.03% | 16.11% | 11.01% | 6.94% | 15.09% | 14.80% | 11.60% | 18.00% |

| Western Europe | 11.14% | 7.85% | 14.44% | 12.90% | 6.09% | 19.72% | 10.51% | 6.76% | 14.25% |

| Other | 16.67% | 11.13% | 22.20% | 16.36% | 6.59% | 26.14% | 16.81% | 10.09% | 23.53% |

| Total | 14.21% | 13.95% | 14.47% | 11.30% | 10.89% | 11.72% | 15.60% | 15.27% | 15.93% |

The prevalence of excess weight was significantly higher in boys compared to girls (15.8 versus 12.5%; p < .000). This difference was sustained across country groups, and was significant in all except Western Europe. We found a very high difference based on sex in children of Chinese descent (21.24% versus 7.3%).

The prevalence of excess weight was also higher in children in the caseloads of primary care teams (PCTs) corresponding to the areas of lowest SES, of 16.7% compared to 13.3% (p < .000). Table 2 shows the differences in excess weight by socioeconomic status and country of origin. It is clear that the differences mainly involve Spanish children.

| Table 2. Prevalence of excess weight by country of origin and socioeconomic status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low socioeconomic status | Middle-high socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | ||||

| Spain | 17.76% | 17.10% | 18.41% | 13.08% | 12.76% | 13.39% | |

| Northwest Africa | 11.76% | 10.42% | 13.10% | 12.91% | 11.39% | 14.42% | |

| India-Pakistan | 14.20% | 12.32% | 16.08% | 15.21% | 12.14% | 18.28% | |

| China-Southeast Asia | 14.57% | 12.19% | 16.95% | 14.00% | 11.32% | 16.68% | |

| Latin America | 23.96% | 20.41% | 27.52% | 21.60% | 18.98% | 24.22% | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 15.80% | 12.77% | 18.83% | 14.87% | 11.34% | 18.40% | |

| Eastern Europe | 9.40% | 6.08% | 12.71% | 16.67% | 13.02% | 20.31% | |

| Western Europe | 11.90% | 2.11% | 21.70% | 11.04% | 7.54% | 14.54% | |

| Other | 22.92% | 11.03% | 34.81% | 14.29% | 8.18% | 20.40% | |

| Total | 16.65% | 16.12% | 17.18% | 13.30% | 13.00% | 13.59% | |

The overall prevalence of dental caries was 17.8%. By nationality, the prevalence was 15.13% in native Spanish children compared to 28.4% of children of non-Spanish descent (p < .000). Table 3 summarises the prevalence of caries by country of origin and age group. The prevalence of caries was higher in children from all countries other than Spain, save for children from other countries in Western Europe, compared to Spanish children. We did not find significant differences between boys and girls. The prevalence increased with increasing age (3.4% versus 25.5%). The difference by age group was sustained across all nationality groups (Table 3).

| Table 3. Prevalence of caries by country of origin and age group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total children | Age 0-5 years | Age 6-14 years | |||||||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | ||||

| Spain | 15.13% | 14.86% | 15.40% | 2.19% | 2.01% | 2.38% | 22.08% | 21.69% | 22.46% |

| Northwest Africa | 37.27% | 35.85% | 38.69% | 10.50% | 9.07% | 11.93% | 54.64% | 52.77% | 56.51% |

| India-Pakistan | 30.17% | 28.22% | 32.12% | 9.26% | 7.26% | 11.26% | 43.02% | 40.35% | 45.69% |

| China-Southeast Asia | 38.61% | 36.39% | 40.82% | 12.81% | 9.96% | 15.65% | 48.98% | 46.28% | 51.67% |

| Latin America | 23.90% | 21.95% | 25.86% | 6.69% | 4.61% | 8.77% | 31.39% | 28.84% | 33.94% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 28.22% | 25.53% | 30.92% | 4.66% | 2.43% | 6.90% | 39.34% | 35.79% | 42.89% |

| Eastern Europe | 28.33% | 25.43% | 31.22% | 11.52% | 8.07% | 14.96% | 37.54% | 33.67% | 41.41% |

| Western Europe | 7.63% | 5.23% | 10.02% | 2.16% | 0.26% | 4.57% | 9.91% | 6.70% | 13.12% |

| Other | 28.77% | 22.68% | 34.87% | 17.65% | 8.59% | 26.71% | 34.03% | 26.29% | 41.77% |

| Total | 17.78% | 17.52% | 18.04% | 3.37% | 3.16% | 3.57% | 25.53% | 25.16% | 25.90% |

The prevalence of caries in the caseloads of PCTs serving low socioeconomic status areas was 27.82% compared to 14.1% in caseloads of higher SES (p < .000). Table 4 presents the prevalence of caries by country of origin and SES. In every comparison, the prevalence was lower in children residing in areas of higher socioeconomic status, although in some cases the confidence intervals did not correspond to statistically significant differences. We also ought to highlight that differences between nationality groups were sustained in both SES groups.

| Table 4. Prevalence of caries by country of origin and socioeconomic status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low socioeconomic status | Middle-high socioeconomic status | |||||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | |||

| Spain | 24.20% | 23.52% | 24.89% | 12.60% | 12.31% | 12.88% |

| Northwest Africa | 40.74% | 38.79% | 42.69% | 33.12% | 31.08% | 35.16% |

| India-Pakistan | 31.47% | 29.12% | 33.82% | 27.07% | 23.59% | 30.55% |

| China-Southeast Asia | 41.54% | 38.54% | 44.53% | 34.85% | 31.57% | 38.13% |

| Latin America | 28.29% | 24.88% | 31.71% | 21.37% | 19.00% | 23.73% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 28.50% | 24.99% | 32.02% | 27.82% | 23.61% | 32.03% |

| Eastern Europe | 31.40% | 26.93% | 35.87% | 25.87% | 22.10% | 29.64% |

| Western Europe | 19.35% | 9.52% | 29.19% | 5.85% | 3.58% | 8.13% |

| Other | 50.91% | 37.70% | 64.12% | 21.02% | 14.65% | 27.39% |

| Total | 27.82% | 27.23% | 28.42% | 14.12% | 13.84% | 14.40% |

We found a prevalence of IDA of 0.75%. The prevalence of anaemia in native Spanish children was 0.5% compared to 1.9% in children of non-Spanish descent (p <.000). Table 5 shows the distribution of the prevalence of IDA by country of origin and socioeconomic status. The prevalence in Indian and Pakistani children was approximately 10 times the prevalence found in Spanish children. We also found a significantly higher prevalence in children from Northwest Africa, and a lower prevalence in Chinese children. The prevalence of IDA was higher in children residing in low SES areas. Anaemia was also more prevalent in boys compared to girls (0.9 versus 0.6; p < .000), and in children aged 6 to 14 years compared to younger children (0.8% versus 0.6%; p = .009).

| Table 5. Prevalence of iron-deficiency anaemia by country of origin and socioeconomic status | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total children | Low socioeconomic status | Middle-high socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | Prevalence | 95 CI | ||||

| Spain | 0.52% | 0.47% | 0.57% | 0.66% | 0.53% | 0.79% | 0.48% | 0.42% | 0.54% |

| Northwest Africa | 1.92% | 1.52% | 2.32% | 1.93% | 1.38% | 2.47% | 1.91% | 1.32% | 2.51% |

| India-Pakistan | 5.40% | 4.44% | 6.36% | 5.60% | 4.44% | 6.76% | 4.94% | 3.24% | 6.63% |

| China-Southeast Asia | 0.16% | 0.02% | 0.35% | 0.10% | -0.09% | 0.28% | 0.25% | -0.09% | 0.59% |

| Latin America | 0.71% | 0.33% | 1.10% | 0.90% | 0.18% | 1.61% | 0.61% | 0.16% | 1.05% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 2.06% | 1.21% | 2.91% | 2.52% | 1.30% | 3.74% | 1.38% | 0.28% | 2.48% |

| Eastern Europe | 0.97% | 0.34% | 1.59% | 1.21% | 0.16% | 2.26% | 0.77% | 0.02% | 1.53% |

| Western Europe | 0.21% | 0.20% | 0.63% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.24% | -0.23% | 0.72% |

| Other | 0.94% | 0.36% | 2.24% | 3.64% | -1.31% | 8.58% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Total | 0.75% | 0.69% | 0.80% | 1.19% | 1.05% | 1.34% | 0.58% | 0.52% | 0.64% |

The prevalence of AD was 15.46%. We did not find differences based on sex. The prevalence of AD was lower in children residing in low SES areas (13.8% versus 16.1%; p < .000). A higher proportion of children aged 6 to 14 years had AD compared to younger children (15.8% versus 14.8%; p = .007). The prevalence was higher in children of Chinese or Northwest African descent, and lower in children from India-Pakistan or Eastern Europe (Table 6).

| Table 6. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis by country of origin and socioeconomic status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | |||

| Prevalence | 95 CI | ||

| Spain | 15.31% | 15.04% | 15.58% |

| Northwest Africa | 18.58% | 17.44% | 19.72% |

| India-Pakistan | 11.70% | 10.34% | 13.07% |

| China-Southeast Asia | 20.46% | 18.63% | 22.30% |

| Latin America | 14.86% | 13.23% | 16.49% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 17.10% | 14.85% | 19.36% |

| Eastern Europe | 9.01% | 7.17% | 10.85% |

| Western Europe | 15.89% | 12.59% | 19.19 |

| Other | 16.04% | 11.10% | 20.98% |

| Total | 15.46% | 15.21% | 15.70% |

DISCUSSION

Studies based on electronic databases, such as this one, have the advantage of having a large number of subjects to analyse. One of the main sources of bias in these studies is under-recording in electronic health records. In this case, we believe that under-recording is probably more frequent in the immigrant population, so that the actual differences may be larger than the differences observed, and in some instances, that we failed to detect significant differences that do exist.

Another possible source of bias associated intrinsically with this type of study is reliability in diagnosis. Since we used retrospective records and data collected by multiple observers, we cannot guarantee the homogeneity of the applied diagnostic criteria.

In this particular study, records concerning the country of origin could also be a limitation, as there is no clear standard for documenting nationality in patients with dual nationality, children born in Spain of immigrant descent, etc.

Since reliable indicators of individual socioeconomic status were not available to us, we attributed to each child the socioeconomic level estimated for the area where they resided, as has been done in previous studies.19

We found a prevalence of excess weight in children aged 0 to 14 years of 14.2%, as can be seen in Table 1, considerably lower compared to the previous literature. Studies that use the WHO growth reference have reported a prevalence ranging from 31% to 41%,15,16,19 although comparisons between studies are challenging. The enKid study,14 which used the 1988 Orbegozo growth tables, found a prevalence of 26.3% in the Spanish population aged 2 to 24 years, also considerably higher compared to the 15.6% found in our study in children aged 6 to 14 years. We believe that these differences may be due to under-recording in our sample and to the use of the 2011 Orbegozo growth tables, which results in lower estimates of the prevalence of overweight in children.

Our study found a higher prevalence of excess weight in the Latin American population, which was consistent with the findings of Cheikk et al.8 and Orsola et al.18

We found a higher prevalence of obesity in boys similar to the prevalence described in the medical literature.14-17 One salient finding was that the prevalence of obesity was higher in boys of Chinese descent compared to boys of Spanish descent, while it was markedly lower in girls of Chinese descent compared to girls of Spanish descent.

Consistent with most of the literature on the subject,15-17 we found an inverse correlation between socioeconomic status and the prevalence of excess weight. This difference was only significant in Spanish children, probably due to the smaller number of children included in all other subgroups under study. It is worth noting that in children from Eastern Europe, the prevalence of obesity was significantly lower in those of low SES compared to those with a higher SES.

The prevalence of dental caries found in our study was approximately half compared to the prevalence found in the 2015 Oral Health Survey.25 In our population of children aged 0 to 14 years, we found a prevalence of 15.13% in the native Spanish group and 28.4% in the non-Spanish group, which diverged from the prevalence found in the Oral Health Survey which, depending on age, ranged from 30% to 42% in native Spanish children and 51.5% to 55% in children of non-Spanish descent.

In agreement with the previous medical literature, we found a higher prevalence of caries in the population of immigrant children of any nationality25-28 with the exception of Western Europe and in association with low socioeconomic status.17,24-26 Needless to say, the prevalence of caries increased with age.

We found a lower prevalence of IDA compared to other studies.2,33 This difference is probably due to gaps in documentation or underdiagnosis. As was the case in the study by Sánchez et al.,33 we found a higher prevalence of IDA in the Indian and Pakistani populations. Although the previous literature describes a higher prevalence of IDA in children aged 6 to 24 months,2 we found a higher prevalence in children aged 6 to 14 years.

Atopic dermatitis is one of the most frequent reasons for seeking dermatological care in the paediatric population.39,40 Our data confirmed the perception of health care professionals of a high prevalence in children of Chinese origin, in agreement with the findings of et al.41

Our findings confirm that some diseases are more prevalent in children of non-Spanish origin. The high incidence of caries in the entire immigrant population is particularly alarming. When it came to the rest of diseases, differences in prevalence were associated with specific regions of origin: obesity in the South American population, iron-deficiency anaemia in the Indian and Pakistani population and atopic dermatitis in the Chinese and Northwest African populations. These prevalence figures justify the development of interventions to improve prevention adapted to the multicultural origins of our population.42

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

AD: atopic dermatitis · BMI: body mass index · CAOD (index): number of teeth with caries, lost or restored (permanent dentition) · COD (index): number of teeth with caries or fillings divided by total number of teeth in the primary dentition · ICD: International Classification of Diseases · ICS: Institut Català de la Salut · IDA: iron-deficiency anaemia · IDIAP: Institut d’Investigació en Atenció Primària · IOTF: International Obesity Task Force · OR: odds ratio · PCT: primary care team · WHO: World Health Organization · 95 CI: 95% confidence interval.

REFERENCES

- Pla de la Diversitat. Recomanacions per a l’Atenció Primària dirigida a usuaris immigrants extracomunitaris. In: Institut Català de la Salut [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://canalsalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/_A-Z/I/immigracio_i_salut/documents/arxius/recopriextra2007.pdf

- Masvidal RM, Canadell D, Grupo de Cooperación, Inmigración y Adopción de la AEPap. Actualización del Protocolo de Atención a las Niñas y Niños Inmigrantes. Revisión 2016. Form Act Pediatr Aten Prim. 2017;10:3-15.

- Comité Consultivo de Bioética de Catalunya. Orientaciones sobre la diversidad cultural y salud. In: Organización Médica Colegial de España [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at https://www.ffomc.org/CursosCampus/Intercultural/Modulo3/curso/03/pdf/anexo4.pdf

- Vázquez ML, Vargas I, Aller MB. Reflexiones sobre el impacto de la crisis en la salud y la atención sanitaria de la población inmigrante. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gac Sanit. 2014;28:142-6.

- Malmusi D, Borrell C, Benach Migration-related health inequalities: showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1610-9.

- Ferrer B, Vitoria I, Dalmau J. La alimentación del niño inmigrante. Riesgos y carencias nutricionales. Acta Pediatr Esp. 2012;70:147-4.

- Vidal M, Ngo J. Recomanacions per al consell alimentari en un entorn de diversitat cultural. Pla Director d’Immigració en l’Àmbit de la Salut: Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya. Barcelona: Direcció General de Planificació i Avaluació; 2007 [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/bitstream/handle/11351/1914/recomanacions_consell_alimentari_entorn_diversitat_cultural_2007.pdf?sequence=1

- Cheikh K, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. Los determinantes sociales de la inmigración infanto-juvenil y su influencia sobre el estado nutricional: revisión sistemática. Nutr Hosp. 2014;30:1008-19.

- Gualdi-Russo E, Zaccagni L, Manzon VS, Masotti S, Rinaldo N, Khyatti M. Obesity and physical activity in children of immigrants. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:40-6.

- Sánchez Echenique M. Aspectos epidemiológicos de la obesidad infantil. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria Supl. 2012;(21):9-14.

- Body mass index for age (5-19 years); 2013. In: World Health Organization [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://www.who.int/growthref/who2007_bmi_for_age/en/

- Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240-3.

- Fernández C, Lorenzo H, Vrotsou K, Aresti U, Rica I, Sánchez E. Estudio de crecimiento de Bilbao. Curvas y tablas de crecimiento. Estudio transversal. Bilbao: Fundación Faustino Orbegozo Eizaguirre; 2011.

- Serra L, Ribas L, Aranceta L, Pérez C, Saavedra P, Peña L. Obesidad infantil y juvenil en España. Resultados del Estudio enKid (1998-2000). Med Clin (Barc). 2003;121:725-32.

- Estudio ALADINO 2015: Estudio de vigilancia del crecimiento, alimentación, actividad física, desarrollo infantil y obesidad en España 2015. In: Agencia Española de Consumo, Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/observatorio/Estudio_ALADINO_2015.pdf

- Sánchez-Cruz JJ, Jiménez-Moleón JJ, Fernández-Quesada F, Sánchez MJ. Prevalence of child and youth obesity in Spain in 2012. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2013;66:371-6.

- Sánchez-Martínez F, Torres P, Serral G, Valmayor S, Castell C, Ariza C. Factores asociados al sobrepeso y la obesidad en escolares de 8 a 9 años de Barcelona. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2016;90:e1-e11.

- Font-Ribera L, García-Continente X, Davó-Blanes MC, Ariza C, Díez E, García MM, et al. El estudio de las desigualdades sociales en la salud infantil y adolescente en España. Gac Sanit. 2014;28:316-25.

- Orsola Lecha E, Pérez Pérez I. Obesidad: estudio de casos en una población infanto-juvenil inmigrante. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2005;7:41-8.

- Escartín L, Mayor EA, Samper MP, Labayen I, Álvarez ML, Moreno LA, et al. Inmigración y riesgo de sobrepeso y obesidad en niños en edad escolar. Acta Pediatr Esp. 2017;75:36-42.

- Casals Peidró E, García Pereiro MA. Guía de práctica clínica para la prevención y tratamiento no invasivo de la caries dental. 2014;19:189-248.

- Alm A. On dental caries and caries-related factors in children and teenagers. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2008;195:7-63.

- Gibson S, Williams S. Dental caries in pre-school children: associations with social class, toothbrushing habit and consumption of sugars and sugar-containing foods. Further analysis of data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of children aged 1.5-4.5 years. Caries Res. 1999;33:101-13.

- Declerck D, Leroy R, Martens L, Lesaffre E, García-Zattera MJ, Vanden Broucke S, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and severity of caries experience in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:168-78.

- Bravo M, Almerich JM, Ausina V, Avilés P, Blanco JM, Canorea E, et al. Encuesta de Salud Oral en España 2015. 2016;21:8-48.

- Cortés FJ, Artázcoz J, Rosel E, González P, Asenjo MA, Sáinz de Murieta I, et al. La salud dental de los niños y adolescentes de Navarra, 2007 (4th edition). An Sist Sanit Navar. 2009;32:199-215.

- Paredes V, Paredes C, Mir B. Prevalencia de la caries dental en el niño inmigrante: estudio comparativo con el niño autóctono. An Pediatr (Barc). 2006;65:337-41.

- Almerich-Silla JM, Montiel-Company JM. Oral health survey of the child population in the Valencia Region of Spain (2004). Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006; 11:E369-81.

- Barriuso L, Sanz B, Hernando L. Prevalencia de hábitos bucodentales saludables en la población infanto-juvenil residente en España. An Pediatr (Barc). 2012;76:140-7.

- Protocolo de diagnóstico, pronóstico y prevención de la caries de la primera infancia. Revisión julio 2017. Sociedad Española de Odontopediatría [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://www.odontologiapediatrica.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/SEOP_-_Caries_precoz_de_la_infancia_fin4.pdf

- WHO Expert Consultation on Public Health Intervention against early childhood caries: report of a meeting, Bangkok, Thailand, 26-28 January 2016. In: World Health Organization [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255627/1/WHO-NMH-PND-17.1-eng.pdf?ua=1

- De Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Congswewll M (eds.). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005. WHO Global Database on Anaemia. In: World Health Organization [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43894/9789241596657_eng.pdf

- Sánchez JM, Yeste D, Marín A, Fernández M, Audí L, Carrascosa A. Evaluación de la anemia ferropénica en niños menores de 6 años de edad de diferentes etnias. Acta Pediatr Esp. 2015;73:120-5.

- Saunders NR, Parkin PC, Birken CS, Maguire JL, Borkhoff CM; TARGet Kids! Collaboration. Iron status of young children from immigrant families. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:1130-6.

- Hayden GF. Skin diseases encountered in a pediatric clinic. A one-year prospective study. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:36-8.

- Albares MP, Ramos JM, Belinchón I, Betlloch I, Pastor N, Botella R. Análisis de la demanda asistencial en dermatología de la población inmigrante. Gac Sanit. 2008;22:133-6.

- Cantarutti A, Donà D, Visentin F, Borgia E, Scamarcia A, Cantarutti L, et al. Epidemiology of frequently occurring skin diseases in italian children from 2006 to 2012: a retrospective, population-based study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:668-78.

- Pérez-Crespo M, Ramos-Rincón JM, Albares-Tendero MP, Betlloch-Más I. Estudio comparativo epidemiológico de la enfermedad cutánea en población infantil inmigrante y autóctona en Alicante. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:394-400.

- Katsarou A, Armenaka M, Kosmadaki M, Lagogianni E, Vosynioti V, Tagka A, et al. Skin diseases in Greek and immigrant children in Athens. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:173-7.

- Pérez-Crespo M, Ramos-Rincón JM, Albares-Tendero MP, Betlloch-Más I. Dermatoses in Latin American immigrant children seen in a universitary hospital of Spain. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:16-20.

- Horii KA, Simon SD, Liu DY, Sharma V. Atopic dermatitis in children in the United States, 1997-2004: visit trends, patient and provider characteristics, and prescribing patterns. 2007;120:e527-34.

- Revisió de la dimensió socioeconòmica de l’assignació de recursos de l’Atenció Primària. In: Agència d’Avaluació i Qualitat Sanitàries de Catalunya [online] [accessed 17/02/2020]. Available at http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_crisi_salut/Fitxers_crisi/Revisio_dimensio_socioeconomica_formula_241116.pdf