Vol. 17 - Num. 68

Evidence based Pediatrics

There is no evidence to recommend azithromycin to prevent recurrent wheezing after bronchioliti

José Cristóbal Buñuel Álvareza

aPediatra. Área Básica de Salud Gerona-4. Instituto Catalán de la Salud. Gerona. España.

Correspondence: JC Buñuel. E-mail: jcbunuel@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Buñuel Álvarez JC. There is no evidence to recommend azithromycin to prevent recurrent wheezing after bronchioliti. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015;17:369-72.

Published in Internet: 01-12-2015 - Visits: 17208

Abstract

Review and assessment of a selected paper.

Authors' conclusions: azithromycin decreases interleukin-8 nasopharyngeal concentration during the study period, and delayed the onset of a subsequent third episode of recurrent wheezing during the monitoring period.

Reviewers' commentary: the results of this trial are not sufficient to recommend indiscriminate use of azithromycin for the treatment of acute bronchiolitis during admission, nor to prevent possible further episodes of recurrent wheezing. If azithromycin actually had any clinically important effect on acute bronchiolitis and its recurrences, it should be demonstrated in a clinical trial specifically designed for this purpose, since the results of a pilot trial cannot be taken as a basis for changes in everyday clinical practice.

Keywords

● Azithromycin ● BronchiolitisINTRODUCTION

The use of a marketed drug for uses that are not approved in its summary of product characteristics (SPC) is known in the scientific literature as off-labeluse. The SPC is a document required by the health authorities prior to the approval of a drug. It contains the information that health care professionals need to know to use the drug safely and effectively. The conditions under which the use of a specific drug is approved may vary between brands marketed by different laboratories in a single country, and also between countries.

Off-label use is most commonly defined in reference to therapeutic indications, use in age subsets, dosages, routes of administration and pharmaceutical forms outside those detailed in the SPC.1,2

The percentage of off-label prescriptions reported in different studies varies depending on the group of drugs analysed, the setting where the prescription is made (specialised care or primary care), and other factors. It is more frequent in hospitals, especially in neonatal, intensive care and surgical wards3-5 (11%‑80% of prescriptions). In the treatment of allergic and/or respiratory diseases, off-label prescriptions account for 3% to 56% of the total, and are issued to up to 78% of the patients.6-8 In the primary care setting, the overall figures reported for off-label prescriptions range between 3% and 67% in different countries.6,9-12 Few studies on the subject have been conducted in Spain, although in primary care, the setting in which most prescriptions are issued, off-label prescriptions amount to 27% to 50% of the total, and 34% to 68% of children are treated with drugs outside their licensed use.13-15 Furthermore, up to 51% of paediatricians acknowledge having prescribed drugs under these conditions.16 Off-label prescriptions are most frequently given to the youngest children worldwide,6-7,10,12,17,18 and antiasthmatics are among the therapeutic groups most frequently used under conditions not approved in the SPC.10-12,17,19

The reason that off-label prescriptions are so common in childhood is that few clinical trials are conducted on the paediatric population, despite the measures implemented by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)20,21 and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).22 As a result, there are few data on the efficacy and safety of the use of many medicines in children. 23-25 In fact, technical information for the paediatric age group is available in the SPC of fewer than 50% of drugs.26

In Spain, the Royal Decree 1015/2009 of June 19, which regulates the availability of medicines under special circumstances, specifies that “this type of prescription will be exceptional, limited to situations in which there are no alternative licensed treatments for a specific patient, and will conform to the restrictions established for its prescription and/or administration and to the care protocol of the health care facility. The prescribing physician will justify the need for the drug in the medical records and inform the patient of the potential risks and benefits of its use, as well as obtain the patient’s consent.”27

Although off-label prescription is not always inappropriate, it seems to be associated with a higher incidence of adverse events that are sometimes severe.4,28-32

The aim of this study was to learn the extent of the off-label prescription of antiasthmatic drugs in the autonomous community of Castilla y León (Spain) in children aged 0 to 14 years during the 2005‑2010 period.

POPULATION AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective observational descriptive study in which we analysed the prescriptions corresponding to the R03 therapeutic subgroup (drugs for obstructive airway diseases) of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) of the World Health Organization.

We obtained the data on the drug utilization from the Pharmacy Information System of Castilla y León (Sistema de Información de Farmacia de Castilla y León [CONCYLIA]), which is not linked to the electronic medical records of the patient. These data correspond to formal prescriptions in the National Health System of Castilla y León (Sistema Nacional de Salud de Castilla y León [SACYL]) ordered by primary care providers between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010 and dispensed in pharmacies.

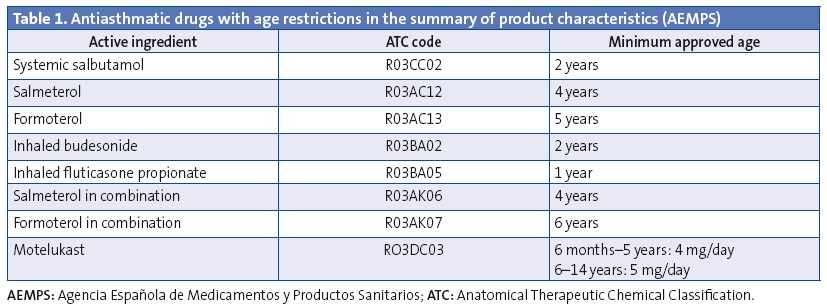

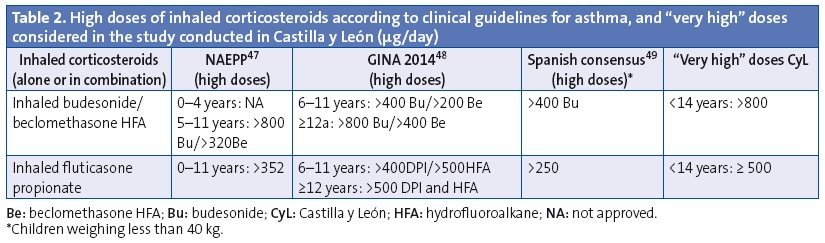

We analysed the prescriptions ordered for children aged less than 14 years, specifically the active ingredient, the age of the patient and the composition and pharmaceutical form. We have summarised the data on off-label prescription as the number of prescriptions for antiasthmatics ordered for ages and/or in doses outside those specified by the corresponding SPCs. Our definition of off-label use also included the prescription of inhaled corticosteroids in doses higher than those defined as “high” by the main asthma guidelines.33-36 These doses also exceed the doses approved by the SPCs (Tables 1 and 2). We consulted the SPCs on the webpage of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Care Products (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios [AEMPS]), the agency in charge of evaluating and approving the marketing of medicines in Spain (www.aemps.gob.es/cima/fichasTecnicas.do?metodo=detalleForm).

Furthermore, to quantify use by age we used the prescribed daily dose (PDD), which is the mean prescribed daily dose of a given drug for its main indication. We calculated the prescribed daily doses taking into account the dosage by age or weight recommended by SPCs of the drugs under study and the main childhood asthma guidelines. We estimated the PDDs for 26 active ingredients in 59 different pharmaceutical forms. To measure the degree of off-label use by age we used the defined daily dose (DDD) per thousand inhabitants per day, which represents that average daily doses prescribed each day to 1000 exposed individuals. We presented more information on the methodology in another article that was published recently.37

The exposed population consisted of children aged less than 14 years holders of a Castilla y León public health card between 2005 and 2010. We obtained the population data from the Technical Directorate of Primary Care (Dirección Técnica de Atención Primaria) of the Regional Department of Health (Gerencia Regional de Salud) of Castilla y León, which serves 96% of the population of this autonomous community. We did not gather any personal information about the patients, information on the prescribing physicians or the specific drug brands prescribed in order to protect confidentiality.

We performed the statistical analysis with SPSS® v.5 and Microsoft Excel®.

RESULTS

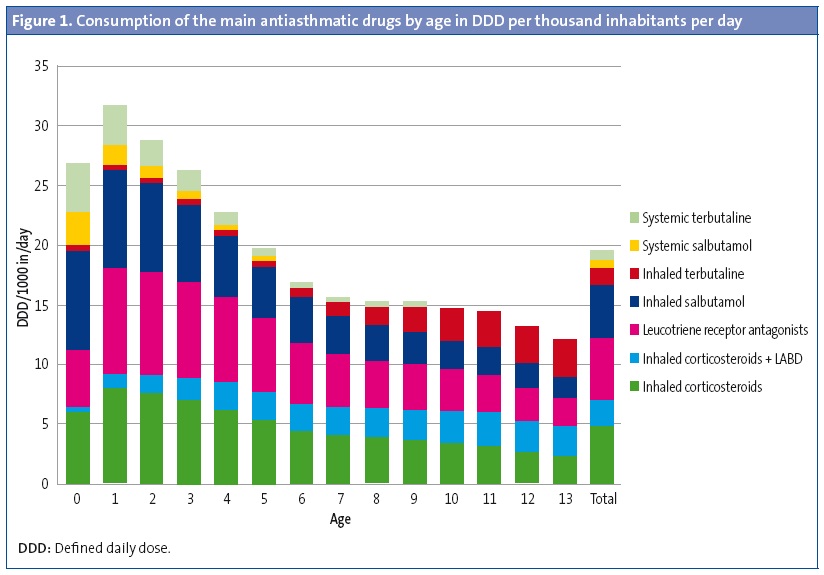

We analysed 394 876 prescriptions for antiasthmatic drugs issued during the period under study in an exposed population of 1 580 229 inhabitants per year. Bronchodilators were the most commonly prescribed antiasthmatics (7.5 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day). Leukotriene receptor agonists were the subgroup most commonly prescribed for maintenance therapy (LTRAs: 5.2 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day), followed by inhaled corticosteroids in monotherapy (ICs: 4.7 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day) and ICs in combination with long-acting bronchodilators (LABD-IC: 2.2 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day) (Figure 1). In infants and preschoolers, antiasthmatics were prescribed more frequently in autumn and winter, and prescriptions decreased by half in the spring. In schoolchildren and adolescents, prescriptions were more frequent in the spring.

The rate of prescription of antiasthmatics was highest in the youngest children, especially in those aged less than 4 years. The consumption of bronchodilators peaked in the first two years of life, and their use stabilised and was much less frequent between ages 6 and 14 years. Inhaled bronchodilators predominated in every age group (6 DDD inhaled/1.5 DDD oral) but systemic bronchodilators were used most extensively in children aged less than 2 years, for whom 45.8% of oral salbutamol containers were prescribed (for off-label use) (Figure 1). The use of LABDs was anecdotal in ages below those in which their use was authorised (11 containers of formoterol for children < 5 years and 41 of salmeterol for children < 4 years).

The drugs most commonly prescribed for maintenance treatment in all age groups were LTRAs (almost solely montelukast), except in infants aged less than 1 year, who were prescribed ICs more often, and children aged 13 years in whom there was a predominance of combined LABD-IC. Consumption of LTRAs peaked at age 1 year (8.9 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day), as did consumption of ICs (7.9 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day); while the use of LABD-CI peaked at 11 years (2.9 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day) (Figure 1).

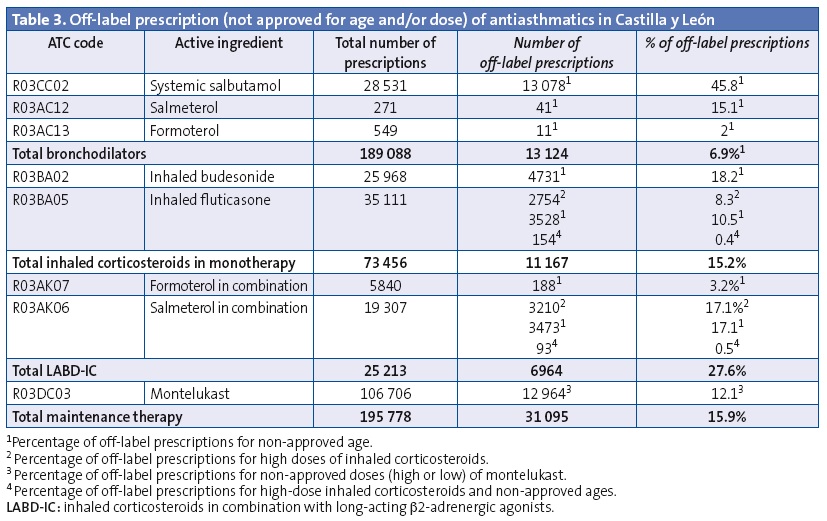

Off-label prescription of a drug for age subsets for which it was not approved and/or in unapproved doses accounted for 15.9% of prescriptions for maintenance therapy. Table 3 presents the results for off-label prescription: combined LABD-IC was prescribed for use starting in the early months of life, and its use increased with age, with 14.8% of the total prescriptions issued for children aged less than 4 years. Twelve percent of the montelukast prescriptions, 18.2% of budesonide prescriptions and 10.5% of fluticasone propionate prescriptions were for use at unauthorised ages. Very high doses of ICs were ordered in 3.9% of IC prescriptions and 13.1% of LABD-IC prescriptions. Thirty-five percent of salmeterol-fluticasone prescriptions were for doses and/or ages outside those specified by the SPC.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to learn the extent of prescription of antiasthmatics in children for their use outside the conditions specified by the SPC in relation to three aspects: therapeutic indication, patient age, and dose. We found that the consumption of antiasthmatic drugs in children less than 4 years of age in Castilla y León was very high, especially in children aged less than 2 years, and it is likely that they were mostly prescribed to treat diseases with symptoms akin to those of asthma for which the indication was either controversial or supported by little evidence. Our study also revealed a considerable use of systemic salbutamol in children aged less than 2 years, for which the use is not authorised in the SPC, and extensive prescription of maintenance treatments not indicated for the particular age of the patient or in doses that exceeded recommendations.

Our study demonstrated that off-label prescription for unauthorised indications is carried out, as we found a high consumption of antiasthmatics in young children. The seasonal pattern in the use of antiasthmatics also supports this hypothesis, as consumption by infants and preschoolers was higher in the autumn and winter, when respiratory infections are more prevalent, and decreased in the spring and summer.37 The spring is the peak season for grass pollen, the major allergen that triggers asthma in children in our autonomous community. Therefore, while we have no data on the actual diagnoses, it seems unlikely that the main indication for the use of antiasthmatics in younger children was asthma.

The use of antiasthmatics for treating young children and their off-label use has been widely documented in the medical literature,4,6,12,14,17,18,38-40 with salbutamol4,6,12,17,18,40 and ICs4,14,17 being the most commonly involved drugs. Some studies have demonstrated39 or inferred6,18,38 that antiasthmatics were used for indications other than asthma.

Besides the use of drugs for unapproved therapeutic indications, the off-label prescription of drugs in children most commonly involves their use outside the authorised age groups,9,14 followed by prescription of doses other than those approved.3,8,10,11,13 In the case of respiratory drugs, off-label use most commonly involves prescription for age groups for which the drug has not been authorised.8 Thus, analysing their use by age in Castilla y León, we found a high consumption of systemic bronchodilators and inhaled budesonide in children younger than 2 years, and a considerable consumption of LABD-IC in children less than 4 years of age. Most salient in the category of systemic bronchodilators was the use of systemic salbutamol in children younger than two years, which is not approved by the SPC; furthermore, oral salbutamol is not recommended by any asthma guideline, as this route of administration is associated with a greater frequency of adverse events and longer onsets of action than the inhalation route. The literature has not often referred to this route of administration for salbutamol, although high consumption of oral salbutamol in children without an asthma diagnosis was reported in the United States for the 2004-2005 period.41

As for combined therapy with LABD-IC (especially salmeterol-fluticasone), our study found that it was prescribed to a small proportion of infants younger than 1 year, but that its consumption in children aged 2 to 3 years was similar to that in children aged 7 to 10 years. This has also been observed in Andalusia42 in children younger than 4 years. The use in children of LABDs, alone or combined with ICs, is controversial due to an apparently higher risk of adverse events. Several studies found a higher risk of severe adverse events, especially hospitalisation, in children treated with LABDs as monotherapy or combined with ICs.43-45 Furthermore, there is little to no data on this risk in children less than 4 years of age. Thus, the extensive use at these ages found by our study is reason for concern.

On the other hand, when we analysed the off-label prescription of antiasthmatics for unauthorised doses we found that 4% of prescriptions for monotherapy ICs and 13% of prescriptions for combined therapy with LABD-CI were for very high doses. This was most frequent in prescriptions for fluticasone and in children older than 4 years. These data are similar to those reported by other studies. Thus, in the United Kingdom (1999‑2000) ICs as monotherapy were the antiasthmatic drugs most commonly prescribed for off-label use at high doses in every age group, but especially in children aged more than 5 years,10 which was attributed to the discrepancy between the doses recommended in the SPCs and by the British asthma guidelines. In the Netherlands (2002),46 8% of children that underwent induction treatment with ICs received doses that far exceeded (doubled) the recommended doses, especially for fluticasone and in children older than 10 years. The authors of the study did not know why such high doses were used, although they believed it may have been due to the availability in the Netherlands of 100, 250 and 500 µg formulations. These formulations are also available in Spain, as well as a 50 µg formulation. In Portugal (2012), it has been reported that the off-label use at doses too high for the patient’s age accounts for nearly half of the fluticasone prescriptions in preschoolers.7 The long-term use of ICs at high or very high doses carries a risk of decreased adult height47 and of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, especially in children receiving daily doses of 500 µg or more of inhaled fluticasone or an equivalent drug.48 These risks should be taken into account, as most children with persistent asthma can achieve adequate control at low to moderate doses of ICs that do not seem to affect linear growth.49 Doses greater than 800 µg a day of budesonide or equivalent are only indicated for children with difficult-to-control asthma (about 2% of asthmatic children in Spain).50

As for montelukast, 12% of the prescriptions in Castilla y León were for doses outside those specified for the corresponding age by the SPC, and 8% were for doses above the maximum recommended. Montelukast has been used in clinical trials51,52 in varying doses (4 and 8 mg) in children less than 36 months and compared with placebo, and no difference was found in the frequency of adverse events between the three groups. However, post-marketing studies have found neuropsychiatric events in every age group, leading the FDA53 to issue a safety alert with recommendations for health care providers in 2009, which the AEMPS also did in 2011.54 Similarly, a study of psychiatric adverse events in patients younger than 18 years between 2001 and 2010 conducted in Sweden found that these events were more frequent and more severe when the drugs were used outside the specifications of the SPC, and montelukast and inhaled budesonide were the drugs most frequently involved55: sleep disorders were the adverse effects most frequently associated with montelukast, while aggressive behaviour was the most frequent adverse effect associated with ICs. The use at high doses and in ages below those for which the drug was approved were the most frequent types of off-label use of these drugs.

Antiasthmatics are one of the therapeutic groups for which adverse reactions are reported most frequently in the paediatric age group, and adverse reactions are more frequent when they are used off-label.28,30 In Sweden (2000)30 antiasthmatics were the therapeutic group associated with the highest number of suspected adverse reactions in non-hospitalised children, and a third of them were associated with off-label prescriptions. Considering that adverse reactions to drugs are reported infrequently and that, as suggested by other studies, many paediatricians may not have been aware of making off-label prescriptions,9,16,56 it is fair to assume that the actual number of adverse reactions was much higher.

Finally, we want to comment that the main limitation of this study is that it only offers a partial view of the off-label prescription of antiasthmatic drugs, as the pharmaceutical database that we used is not linked to the electronic medical histories of the patients. Thus, we do not know the diagnoses for which the drugs were prescribed, and we estimated the doses based on the formulations used for each age and the dosage recommended in the SPCs. We also could not find information on the severity of asthma or the duration of antiasthmatic treatment. However, the reference population and its size are strengths of the study. The prescriptions we analysed probably amount to 65% of the antiasthmatics consumed by children aged less than 14 years in Castilla y León during the period under study,37 which allows for an accurate assessment of this type of prescription in our autonomous community.

In conclusion, this study provides partial knowledge on the off-label prescription of antiasthmatics in the paediatric population of the autonomous community of Castilla y León in a recent period. We found that the consumption of antiasthmatic drugs peaked at ages in which the diagnosis of asthma was unlikely, and demonstrated their use at ages and in doses for which the risk-benefit ratio may be unfavourable. While off-label prescription may be necessary and appropriate, it should be based on rigorous scientific criteria and seek to benefit the patient.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABREVIATURAS: AEMPS: Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios • LTRA: leukotriene receptor agonist • PC: Primary Care • ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification. ICs: inhaled corticosteroids • CONCYLIA: Pharmacy Information System of Castilla y León • EMA: European Medicines Agency • FDA: Food and Drug Administration • PDD: prescribed daily dose • DDD: defined daily dose • SACYL: National Health System of Castilla y León • LABD: long-acting bronchodilator.

REFERENCES

- Neubert A, Wong IC, Bonifazi A, Catapano M, Felisi M, Baiardi P, et al. Defining off-label and unlicensed use of medicines for children: Results of a Delphi survey.Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:316-22.

- Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards: Prospective study. BMJ. 1998;316:343-5.

- Pandolfini Ch, Bonati M. A literature review on off-label drug use in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:552-8.

- Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, Mohn A, Arnell H, Rane A, et al. Survey of unlicensed an off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. BMJ. 2000;320:79-83.

- Lindell-Osuagwu L, Korhonen MJ, Saano S, Helin-Tanninen M, Naaranlahti T, Kokki H. Off-label and unlicensed drug prescribing in three paediatrics wards in Finland and review of the international literature. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:277-87.

- Baiardi P, Ceci A, Felisi M, Cantarutti L, Girotto S, Sturkenboom M, et al. In-label and off-label use of respiratory drugs in the Italian paediatric population. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:544-9.

- Morais-Almeida M, Cabral AJ. Off-label prescribing for allergic diseases in pre-school children. Allergol Immunopathol (Madrid). 2014;42:342-7.

- Silva D, Ansotegui I, Morais-Almeida M. Off-label prescribing for allergic diseases in children. World Allergy Ongan J. 2014;7:4.

- Chalumeau M, Treluyer JM, Salanave B, Assathiany R, Cheron G, Crocheton N, et al. Off-label and unlicensed drug use among French office based paediatricians. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:502-5.

- Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ, Simpson CR, Taylor MW, McLay JS. Off-label prescribing to children in primary care: retrospective observational study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:349-53.

- Gavrilov V, Lifshitz M, Levy J, Gorodischer R. Unlicensed and off-label medication use in a General Pediatrics Ambulatory Hospital unit in Israel. IMAJ. 2000;2:595-7.

- Bazzano AT, Mangione-Smith R, Schonlau M, Suttorp MJ, Brook RH. Off-label prescribing to children in the United States outpatient setting. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:81-8.

- Morales-Carpi C, Estañ L, Rubio E, Lurbe E, Morales-Olivas FJ. Drug utilization and off-label drug use among Spanish emergency room paediatric patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:315-20.

- Blanco-Reina E, Vega-Jiménez MA, Ocaña-Riola M, Márquez Romero EI, Bellido-Estévez I. Estudio de las prescripciones farmacológicas en niños a nivel de atención primaria: evaluación de los usos off-label o fuera de ficha técnica. Aten Primaria. 2014;47:344-50.

- Garcia Blanes CP, Rodríguez-Cantón Pascual P, Morales-Carpi C, Morales-Olivas FJ. ¿Se ha modificado el uso de antitérmicos tras la introducción de ibuprofeno a diferentes concentraciones? An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:383-8.

- Piñeiro Pérez R, Ruiz Antorán MB, Avendaño Solá C, Román Riechmann E, Cabrera García L, Cilleruelo Ortega MJ, et al. Conocimiento sobre el uso de fármacos off-label en Pediatría. Resultados de una encuesta pediátrica nacional 2012-2013 (estudio OL-PED). An Pediatr (Barc). 2014;81:16-21.

- Jong GW, Eland IA, Sturkenboom MC, van den Anker JN, Strickerf BH. Unlicensed and off-label prescription of respiratory drugs to children. Eur Respir J. 2004;7:310-3.

- Sen EF, Verhamme KM, Neubert A, Hsia Y, Murray M, Felisi M, et al. Assessment of pediatric asthma drug use in three European countries; a TEDDY study. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:81-92.

- McCowan C, Hoskins G, Neville RG. Clinical symptoms and 'off-label' prescribing in children with asthma. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:220-2.

- Wharton GT, Murphy MD, Avant D, Goldsmith JV, Chai G, Rodríguez VJ, et al. Impact of pediatric Exclusivity on drug labeling and demonstrations of efficacy. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e512-e518.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committe on Drugs. Off-label use drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2014;133:563-7.

- Informe de la comisión al parlamento europeo y al consejo. Mejores medicamentos pediátricos. Del concepto a la realidad. In: Comisión Europea [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/paediatrics/2013_com443/paediatric_report-com(2013)443_es.pdf

- Peiré García MA. Importancia de la farmacología clínica en pediatría. An Pediatr (Barc). 2010;72:99-102.

- Valls-i-Soler A, Santesteban E, Campino A. Mejores medicamentos en Pediatría. An Pediatr (Barc). 2011;75:85-8.

- Bravo Acuña J. Mesa Redonda. Uso de fármacos off-label en las diferentes disciplinas pediátricas. Libro de ponencias y comunicaciones. Congreso extraordinario de la Asociación Española de Pediatría 2014 (p. 184). In: Congresoaep.org [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in www.congresoaep.org/2014/readcontents.php?file=webstructure/01_sesiones_cientificas_oficiales.pdf

- Sachs AN, Avant D, Lee CS, Rodriguez W, Murphy MD. Pediatric information in drug product labeling. JAMA. 2012;307:1914-5.

- Real Decreto 1015/2009 por el que se regula la disponibilidad de medicamentos en situaciones especiales. Boletín Oficial del Estado número 174 de lunes 20 de julio del 2009. Available in www.boe.es/boe/dias/2009/07/20/pdfs/BOE-A-2009-12002.pdf

- Turner S, Nunn AJ, Fielding K, Choonara I. Adverse drug reactions to unlicensed and off-label drugs on paediatric wards: a prospective study. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:965-8.

- Evidence of harm from off-label or unlicensed medicines in children; EMA/11207/04. In: European Mecicines Agency [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2009/10/WC500004021.pdf

- Ufer M, Kimland, E, Bergman U. Adverse drug reactions and off-label prescribing for paediatric outpatients: a one-year survey of spontaneous reports in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:147-52.

- Mason J, Pirmohamed M, Nunn T. Off-label and unlicensed medicine use and adverse drug reactions in children: a narrative review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:21-8.

- Horen B, Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Adverse drug reactions and off-label drug use in paediatric outpatients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:665-70.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Full report 2007. In: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf

- Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Revised 2014. In: Global Initiative for Asthma [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015, actualizado en 2014]. Available in www.ginasthma.org

- Castillo JA, de Benito J, Escribano A, Fernández M, García de la Rubia S, Grupo de trabajo para el Consenso sobre Tratamiento del Asma Infantil. Consenso para el tratamiento del asma en Pediatría. An Pediatr (Barc). 2007;67:253-73.

- British guideline on the management of asthma. In: SIGN [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015, actualizado en octubre de 2014]. Available in www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN141.pdf

- Casares-Alonso I, Cano-Garcinuño A, Blanco-Quirós A, Pérez-García A. Anti-asthmatic prescription variability in children according to age. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2015;43:383-91.

- Bisgaard H, Szfler S. Prevalence of asthma-like symptoms in young children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:723-38.

- Ochoa Sangrador C, González de Dios J, Grupo investigador del proyecto aBREVIADo (BRonquiolitis-Estudio de Variabilidad, Idoneidad y ADecuación). Manejo de la bronquiolitis aguda en atención primaria: análisis de la variabilidad e idoneidad (proyecto aBREVIADo). An Pediatr (Barc). 2013;79:167-76.

- Ribeiro M, Jorge A, Macedo AF. Off-label Drug prescribing in a Portuguese paediatric emergency unit. Int J Clin Pham. 2013;35:30-6.

- Korelitz JJ, Zito JM, Gavin NI, Masters MN, McNally D, Irwin DE, et al. Asthma-related medication use among children in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:222-9.

- Praena Crespo M, Lora Espinosa A, Murcia Garcia J, Rodriguez Castilla J. Uso racional de medicamentos en el asma y en el menor de tres años con sibilancias. In: AEPap. Curso de Actualizacion en Pediatría 2011. Madrid: Exlibris Ediciones; 2011. p. 391-4.

- McMahon AW, Levenson MS, McEvoy BW, Mosholder AD, Murphy, D. Age and risks of FDA-approved long-acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonists. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1147-e1154.

- Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodríguez JA. Safety of long-acting beta agonists for the treatment of asthma: clearing the air. Thorax. 2012;67:342-9.

- Cates CJ, Cates MJ. Regular treatment with formoterol for chronic asthma: serious adverse events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006923.

- Schirm E, de Vries TW, Tobi H, van den Berg PB, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Prescribed doses of inhaled steroids in Dutch children: too little or too much, for too short a time. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:383-90.

- Pruteanu AI, Chauhan BF, Zhang L, Prietsch SO, Ducharme FM. Inhaled corticosteroids in children with persistent asthma: is there a dose response impact on growth? An overview of Cochrane reviews. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015;16:51-2.

- Smith RW, Downey K, Gordon M, Hudak A, Meeder R, Barker S, et al. Prevalence of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression in children treated for asthma with inhaled corticosteroid. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:e34-e39.

- Smyth AR, Barbato A, Beydon N, Bisgaard H, de Boeck K, Brand P, et al. Respiratory medicines for children: current evidence, unlicensed use and research priorities. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:247-65.

- Plaza-Martín AM, Vennera MC, Galera J, Herráez L, PREX Study Group. Prevalence and clinical profile of difficult-to-control severe asthma in children: Results from pneumology and allergy hospital units in Spain. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2014;42:510-7.

- Bisgaard H, Study Group on Montelukast and Respiratory Syncitial Virus. A randomized trial of montelukast in respiratoty syncytial virus postbronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:379-83.

- Bisgaard H, Flores-Nunez A, Goh A, Azimi P, Halkas A, Malice MP, et al. Study of montelukast for the treatment or respiratory symptoms of post-respiratory syncitial virus bronchiolitis in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:854-60.

- Leukotriene Inhibitors: Montelukast (marketed as Singulair), Zafirlukast (marketed as Accolate), and Zileuton (marketed as Zyflo and Zyflo CR). 2009. In: FDA. Safety information [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm166246.htm

- Información sobre seguridad. Montelukast: notificación de casos de reacciones psiquiátricas. In: AEMPS [online] [consulted on 27/08/2015]. Available in www.aemps.gob.es/informa/informeMensual/2011/febrero/informe-medicamentos.htm

- Byddell M, Brunlöf G, Wallerstedt SM, Kindblom JM. Psychiatric adverse drug reactions reporting during a 10-year period in the Swedish pediatric population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;2179-86.

- Marchetti F, Bua J, Ventura A, Notarangelo LD, Di Maio S, MiglioriG, et al. The awareness among paediatricians of off-label prescribing in children: a survey of Italian hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:81-5.