Vol. 17 - Num. 67

Original Papers

Sexual behavior in adolescents 13 to 18 years old

María Alfaro Gonzáleza, Marta Esther Vázquez Fernándezb, Ana Fierro Urturic, M.ª Fe Muñoz Morenod, Luis Rodríguez Molineroe, Carolina González Hernandof, Grupo de Educación para la Salud de la AEPap

aServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Medina del Campo. Valladolid. España.

bPediatra. CS Arturo Eyries. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

cPediatra. CS Pisuerga. Arroyo de la Encomienda. Valladolid. España.

dUnidad de Investigación Biomédica. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

eServicio de Pediatría. Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande. Valladolid. España.

fMatrona. CS Arturo Eyríes. Profesora. Facultad de Enfermería. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

Correspondence: M Alfaro. E-mail: mariaalfaro28@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Alfaro González M, Vázquez Fernández ME, Fierro Urturi A, Muñoz Moreno MF, Rodríguez Molinero L, González Hernando C, et al. Sexual behavior in adolescents 13 to 18 years old. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2015;17:217-25.

Published in Internet: 09-09-2015 - Visits: 320497

Abstract

Introduction: the adolescent population is particularly vulnerable to the risks related with their sexual behavior, because it is a period of maturation and experience which is part of this evolutionary stage. Teenage pregnancy and early motherhood are associated with school failure, impaired physical and mental health, social isolation, poverty and other related factors. Moreover the non-use of appropriate protective barriers increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI), with serious consequences in the short and long term biopsychosocial adolescent health.

Objectives: to determine the characteristics of adolescent sexuality in the province of Valladolid.

Methods: cross-sectional study, using an anonymous survey to 2412 schoolchildren 13-18 years old in the academic year 2011-2012.

Results: 81% of students feel they have very good or good information on sexuality. 75% of students believe that the information they have about STI is very good or good. 30.4% have had sexual intercourse. The age of first complete sexual intercourse is between 15 and 16 years (50.9%). Most of the adolescents use a contraceptive method in their relationships (91.3%), but there are still 8.7% referring not using any. Most of the students use the condom for contraceptive method (89.6%). 20.9% of teens who have had sex with penetration have used “the morning-after pill” or emergency contraception at some time. 3.6% reported having being pregnant or having left his partner pregnant.

Conclusions: although they consider themselves sufficiently informed about sexuality and STI, adolescents present risk behaviors in their sexual activities.

Keywords

● Adolescent ● Contraceptive methods ● Pregnancy ● SexualityINTRODUCTION

One of the tasks facing the adolescent is to develop responsible behaviours in relation to sexuality, with all its physical and psychological implications. Adolescence is a maturation period during which experimentation is normal. In the final report specifying the main European health policy strategies for the first two decades of the XXI century agreed on at the Fifty-First World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization (WHO) held in May 1998,1 the healthcare community declared the adolescent population to be particularly vulnerable to risks associated with sexual behaviour, and they presented the following considerations, which are still fully relevant:

- Unprotected sexual activity results in a large number of unwanted pregnancies, abortions and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including infection by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- In many parts of Europe, unbiased and objective sex education is not being provided either in schools or in other settings.

- The lack of information and understanding about issues to do with sexuality, bodily changes and functions and emotional feelings causes unnecessary emotional stress.

- There are not enough confidential health services developed with youth in mind. This lack may limit the access of youth to adequate health care and counselling.

In developed countries, a large proportion of the adolescents that complete compulsory education report having engaged in risky sexual behaviours.2,3 Unprotected sex or incorrect use of protective measures carry a risk of unwanted pregnancy, with the corresponding negative consequences for this age group, such as abortion, early motherhood or adoption.4 Adolescent pregnancy and early motherhood are associated with school failure, a decline in physical and mental health, poverty and other related factors. Furthermore, failure to use appropriate protective barriers increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections, with short- and long-term consequences for the biopsychosocial health of adolescents.5

For all the above reasons, addressing sexual health in adolescents by increasing their commitment to safe sex has become a significant challenge in developed countries.5,6

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference population and sample

The sample universe consisted of secondary education students aged 13 to 18 years. We selected the sample based on the population enrolled in schools or educational institutions offering second, third and fourth year of compulsory secondary education (Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria [ESO]) or first and second year of non-compulsory secondary education (Bachillerato LOGSE). This framework influenced the age distribution of the sample.

This study did not include students aged 13 to 18 years enrolled in elementary education, college or vocational school, those that did not attend school the day and time that the questionnaire was administered (absent students), students enrolled in regular education tracks (Enseñanzas de Régimen General) in social equality and distance programmes (Programas de Garantía Social y a distancia), night school tracks (Enseñanzas de Régimen Nocturno) and special education tracks (Enseñanzas de Régimen Especial).

Sample

We selected students by multistage cluster sampling, randomly selecting schools in the first stage (n=14) and classes in the second. All students in the selected classes were included in the study.

The sample size was calculated for an estimated proportion of 50% and a precision of 2.5% in a two-tailed comparison, assuming a 10% nonresponse rate, which resulted in 1566 students. The final number of surveyed students clearly exceeded the estimated size after cleaning the data and removing incomplete questionnaires; the final sample included 2412 adolescents enrolled in school aged between 13 and 18 years.

Questionnaire and fieldwork

The instrument we used to collect the data was a 101-item questionnaire adapted from and similar to already validated questionnaires used in other studies conducted internationally,7,8 in Spain,9,10 and in different autonomous communities and provinces.11-15

The items asked questions relating to sociodemographic variables, academic performance, entertainment and leisure, accidents, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, behaviours, history of abuse and interpersonal relationships, nutrition and sexuality.

The questionnaire was filled out anonymously by each participant on a voluntary basis during school hours; it was administered by computer in 69% of respondents and in paper form (paper and pencil) in the remaining 31%. The time spent filling out the questionnaire was 35 to 40 minutes.

The research team administered the questionnaire, sometimes with the help of the teaching staff. All questionnaires were administered between March and May 2012.

The study design was approved by the Research Committee of the Primary Care Administration of the Área Oeste (West Health Area) of Valladolid.

Statistical analysis

We have expressed quantitative variables as mean and 95% confidence interval, and qualitative variables as distributions of frequencies.

We analysed the data with the software package SPSS® version 19.0 for Windows®. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

RESULTS

Of all responses, a total of 2412 questionnaires were considered valid; 47.3% corresponded to girls and 52.7% to boys. As for school year, 23.5% were enrolled in second year of the ESO; 25.8% in third year of the ESO; 20.2% in fourth year of the ESO; 18.9% in first year of Bachillerato and 11.6% in second year of Bachillerato.

Level of information on sexuality

Eighty-one percent of the students considered that they were well or very well informed on the subject of sexuality. Boys considered that they were well informed more than girls (84.1% versus 77.5%; P < .001). Only 3.9% reported having gained little to no knowledge about sexuality, with second-year ESO students reporting most frequently to be poorly informed or not at all (7.7% compared to 2.2% in 1st year of Bachillerato; P < .001).

Level of information on sexually transmitted diseases

Seventy-five percent of respondents considered that they were well or very well informed on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), a percentage that was higher in boys (78.2%) than in girls (71.7%) (P < .001). However, 6.1% of respondents considered that they were poorly informed or not at all about STDs. Students in lower years reported being inadequately informed most frequently (12.8% of second-year ESO students year compared to 3.2% of second-year Bachillerato students; P < .001).

Sexual guidance

When asked whom they would seek guidance on sexuality from, 59.3% answered that they would talk to their friends, and 51.7% with their parents. The third most frequent source was searching the web (27.8%). The fourth was seeking information from healthcare professionals (19.9%), with no differences between boys and girls. Fewer would talk to their teachers (8.8%) or to other individuals (5.2%), and 7.7% stated they would not talk to anyone.

Frequency of intercourse

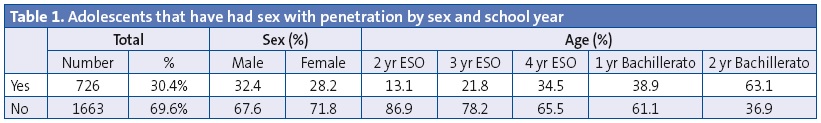

Of all students, 30.4% had had sex with penetration at least once. The percentage of boys that reported having had intercourse (32.4%) was higher than the percentage of girls (28.2%) (P = .028). As students advanced to upper years, the frequency with which they had had intercourse increased, so that 13.1 % of second-year ESO students had had intercourse compared to 63.1% of second-year Bachillerato students (P < .001; Table 1).

Of all participants, 5.2% reported having had sex with penetration only once; 8.25% having intercourse a few times a year (less than once a month); 11.13% having intercourse several times a month; and 5.82% several times a week.

Age at first intercourse

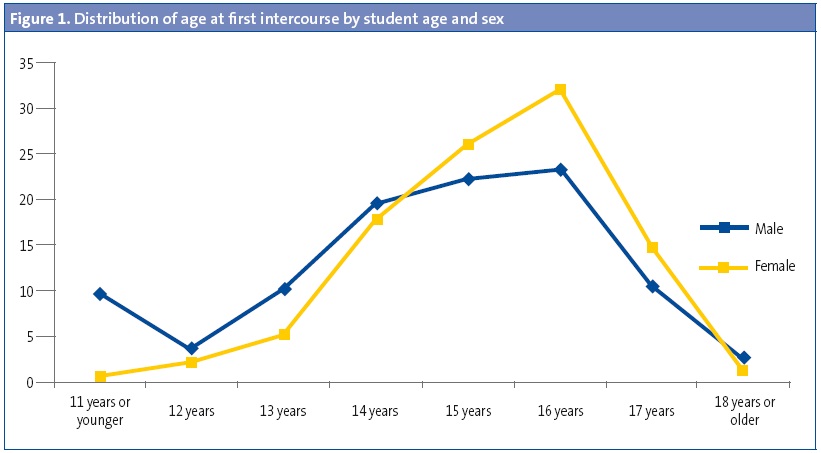

The age at first intercourse was between 15 and 16 years (50.9%). A significantly higher percentage of girls had their sexual debut in this age range (58%) compared to boys (45.4%) (P < .001). First intercourse took place between 13 and 14 years of age in 18.8%, after age 17 years in 13.9%, and before age 12 years in 8.4%. Figure 1 shows the distribution by age and sex.

The differences by school year were significant (P < .001), with students in lower years reporting younger ages at first intercourse than students in upper years. Thus, 35.7% of second-year ESO students reported having first had sexual intercourse at age 12 years or younger, compared to 2.8% of second-year Bachillerato students.

Sexual activity

Of the respondents that had had intercourse, 91.3% had had intercourse within the past year. Among them, 57% had only had sex with one partner, 14.2% with two partners, and 20.1% with more than two partners. Girls reported having had sex only with the person they were dating more frequently than boys (69% versus 47.5%), a difference that was statistically significant (P < .001), and boys reported having had sex with more than two partners more often than girls (27.5% versus 10.7%). In terms of the school year, the older students in second year of Bachillerato had the most stable relationships, with 63.4% reporting having sex only with their girlfriend or boyfriend compared to 49.3% of second-year ESO students. Meanwhile, second-year ESO students reported having had sex with two or more partners most frequently (28.8%), a percentage that decreased as the school year increased (13.7% in second-year Bachillerato students).

Contraceptive methods

Most respondents reported using some type of contraceptive method in their sexual relations (91.3%), but 8.7% reported using none. We found no differences based on sex. The students that reported not using any contraceptive methods most frequently were in third year of the ESO (15.8%), followed by second year of the ESO (12.3%), second year of Bachillerato (7.4%), fourth year of ESO (6%) and first year of Bachillerato (5.7%) (P = .009).

Most respondents used condoms for contraception (89.6%). There were no significant differences between sexes. We did find differences between school years (P = .002), with the use of condoms increasing with the age of the respondents.

Birth control pills were used by 8.6% of the students. There were no statistically significant differences by sex or school year.

The rhythm method (ovulation date calculation) was used by 1.5%, and the pulling out method by 9.5%. To a lesser degree, respondents used spermicides (1%), the diaphragm (0.8%) and intrauterine devices (0.6%). Three percent reported using other contraceptive methods.

When asked whether they had refrained from having sex due to not having a condom, 58.8% answered that they had, with a significantly higher proportion of girls (71.7%) compared to boys (48.5%) (P < .001). This percentage was higher in first-year (65.3%) and second-year (61.5%) Bachillerato students than in students in lower grades (2nd year of the ESO, 45.2%) (P = .029).

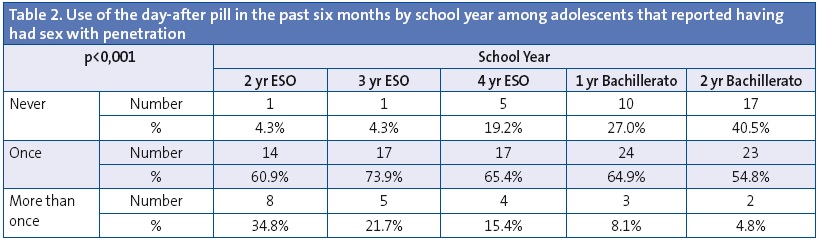

Among the teenagers that had engaged in sexual intercourse, 20.9% reported having used the day-after pill at least twice; 16.1% had used it in the last six months, and 3% had resorted to emergency contraception more than once in the past six months. As for the distribution by school year, the highest percentage of respondents that reported having used this method corresponded to students enrolled in the second year of the ESO (31.5%), followed by students in the second year of Bachillerato (24%), first of Bachillerato (20.7%), third of the ESO (18%) and fourth of the ESO (15.6%) (P = .05). When it came to its use in the past six months, there was a significantly greater percentage in students of lower years, both for having used it once and more than once, as can be seen in Table 2.

Of all students, 3.6% reported having become pregnant or made their partner pregnant (5.3% of boys and 1.3% of girls). There was a statistically significant higher proportion of students of 2nd year of the ESO that reported pregnancy (9.9%; P < .001), with the proportion declining in students in upper years (1.8% in year two of Bachillerato). Among the boys, 11.4% did not know whether they had made their partner pregnant, while 3.3% of the girls reported not knowing whether they were pregnant.

Sex, drugs and alcohol

Of all respondents, 23.4% reported having consumed alcohol and/or drugs the last time they engaged in sexual intercourse. The percentage was significantly higher (P < .001) in boys (29.2%) than in girls (16%). The differences by school year were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Adolescence is a period of development and growth, particularly in the area of affect and sexuality. Although affective and sexual development takes place through the entire lifespan, the individual undergoes significant changes during this stage. In Spain, many youth start having their first sexual relations during these years. This involves numerous health and wellness risks for these youth, such as early pregnancy, STIs, forced sexual relations, or feelings of disappointment or regret following sexual relations. The emotional, healthcare and economic costs of these risks highlight the importance of studying sexual debut in youth and its associated elements.

In general terms, this study of sexual behaviour showed that nearly one third of adolescents (30.4%) report having had intercourse at least once in their lives. This percentage rises with the age of the respondents, exceeding 60% by the second year of Bachillerato, with a higher incidence in male students. Nevertheless, in approximately half the students these were sporadic relations (once in their lives or a few times a year). These data are similar to those found in the HBSC study.9 The SIVFRENT study,16 conducted on adolescents in the Autonomous Community of Madrid, showed a slightly higher percentage (34.6%) and no differences between sexes. The Observatorio de Salud (Health Observatory) of Terrasa has also found higher percentages of history of intercourse (36% in 2010), and higher percentages among females.12

In our study, 91.3% of the respondents that had had intercourse reported having used some type of contraceptive measure the last time they had sex, especially condoms. The second most-used contraceptive method was the pill. The remaining contraceptive methods (diaphragm, spermicides, IUD and others) were used by very small percentages, perhaps due to ignorance, cost, or unavailability. Also, more than 10% reported using “pulling out” and/or the rhythm method for contraception.

Another important finding was that a high proportion of participants reported having used emergency contraception or the “day-after pill” once or more in the past few months. The current legislation allows all adolescents to obtain it without a prescription, and there is an increasing number of youth that use it after having sexual intercourse without a condom or another contraceptive method. It is not clear whether the unrestricted availability of the drug has reduced the incidence of unwanted pregnancy among female adolescents, although the Ministry of Health has announced that the number of abortions has decreased. In our study, the discrepancies between the results of boys and girls and of older and younger students prevented us from corroborating this trend.

In our survey, the frequency of condom use was slightly above the one reported in other Spanish studies. Sexual health campaigns have had a significant impact on the frequency of condom use among our youth. According to the Informe de la Juventud en España (Report on Youth in Spain), there has been an increase in the use of condoms among younger adolescents.17 One noteworthy finding was that 73.8% of adolescents aged 15 to 17 years reported having used a condom every time in the past year. This percentage dropped to 64.3% in youth aged 18 to 20 years and to 54.1% among those aged 21 to 24 years. However, this marked improvement in the use of condoms seems to be accompanied by an increase in high-risk sexual behaviours and alcohol consumption. One out of four respondents had sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Different studies show a tendency to have first intercourse at increasingly early ages.18 According to the Encuesta de Salud y Hábitos Sexuales (Sex Habits and Health Survey [ESHS]),19 16.5% of individuals aged 18 to 29 years in Spain had sex with penetration for the first time before the age of 16. As a consequence, a new group is emerging in voluntary termination of pregnancy (VTOP) comprising minors younger than 16 years that did not exist a few years ago.20 This trend was confirmed by our study, as we observed that students in lower years had sex for the first time at younger ages than students in upper years.

As the age at first intercourse decreases and the age at which families are formed increases, the period during which youth are sexually active becomes longer, and they have a larger number of partners. The sexual lifestyle of adolescents and young adults is characterised by establishing a series of short-term monogamous partnerships in the context of a romantic relationship. Adolescents and young adults consider relationships to be stable when they last for a period of time that is relatively short compared to preceding generations.21 In our study, 34.3% had had sex with two or more partners in the past year, which was more frequent among second-year ESO students than among second-year Bachillerato students, as the latter were more likely to be in a stable relationship. When we analysed the sexual health campaigns targeting youth of the Spanish Ministry of Health from the past few years, we did not find any recommendations regarding a reduction in the number of sexual partners.22 These campaigns only promoted the use of condoms for the entire population.

There was a high percentage of adolescents (14%), consistent with other studies, that did not use safe methods to prevent unwanted pregnancies and STIs, and even 8% that did not use any method, which reveals an ignorance of preventive measures, especially among younger individuals. This finding stood in contrast with the fact that most adolescents believed themselves to be well or very well informed on the subject of sexuality and STDs.

Friends were the main source of information, followed by parents and then by the mass media and the Internet, consistent with other studies.23-25 This highlights the importance of the quality of web and media contents, and the effectiveness of providing web pages and secure applications to search for information, which should target the parents but also the adolescents, as the latter will undoubtedly become sources of information, especially for their peers.

CONCLUSIONS

We must promote an integral sexual education for adolescents, so that youth can make responsible decisions about their sexual health, not feel pressured to start engaging in sexual activity, and avoid contracting an STI or facing an unwanted pregnancy.26 A reduction in the incidence of problems like STIs or early pregnancies can only be achieved through improvements in lifestyle habits, which would necessarily involve sexual education. It is unlikely that this will result from isolated educational interventions.27,28 Thus, a greater effort is required from health authorities and professionals to promote sexual awareness and education campaigns addressing our youth.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics (Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria [AEPap]).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS: ESO: compulsory secondary education • HIV: human immunodeficiency virus • STD: sexually transmitted disease • STI: sexually transmitted infection • WHO: World Health Organization.

REFERENCES

- OMS. Salud 21. El marco político de salud para todos de la Región Europea de la OMS. En: Federación Andaluza de Municipios y Provincias [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en www.famp.es/racs/intranet/otras_secciones/documentos/SALUD%2021.pdf

- Avery L, Lazdane G. What do we know about the sexual and reproductive health of adolescets in Europe? Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:58-70.

- Godeau E, Nic Gabhainn S, Vignes C, Ross J, Boyce W, Toodd J. Contraceptive use by 15-year-old students at their last sexual intercourse: results from 24 countries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:66-73.

- Ellison MA. Authoritative knowledge and single women's unintentional pregnancies, abortions, adoptions and single motherhood. Social stigma and structural violence. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:322-47.

- Estrategia mundial de prevención y control de las infecciones de transmisión sexual 2006-2015: romper la cadena de transmisión. En: OMS [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43773/1/9789243563473_spa.pdf

- Public choices, private decisions: sexual and reproductive health and the millennium development goals. En: UN Millennium Project [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/MP_Sexual_Health_screen-final.pdf

- Brooks F, Van der Sluijs W, Klemera E, Morgan A, Magnusson J, Gabhainn SC, et al. Young people’s health in Great Britain and Ireland. Findings from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. HBSC International Coordinating Centre. Edimburgo: University of Edinburgh; 2006.

- Adolescent questionnaire. California Health Interview Survey 2010. En: Universidad de California [en línea] [consultado el 01/08/2015]. Disponible en www.chis.ucla.edu

- Moreno-Rodríguez C, Muñoz Tinoco V, Pérez Moreno PJ, Sánchez Queija I, Granado Alcón MC, Ramos Valverde P, et al. Desarrollo adolescente y salud. Resultados del estudio HBSC 2006 con chicos y chicas españoles de 11-17 años. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2008.

- Nebot M, Pérez A, García-Continente X, Ariza C, Espelt A, Pasarín M, et al. Informe FRESC 2008. Resultats principals. Barcelona: Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona; 2010.

- Dirección General de Salud Pública y Participación de la Consejería de Salud y Servicios Sanitarios del Principado de Asturias. Encuesta de Salud Infantil en Asturias, 2009. Observatorio de la Infancia y la Adolescencia del Principado de Asturias [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en www.observatoriodelainfanciadeasturias.es/cifras_02

- Schiaffino A, Moncada A, Martín A. Estudi EMCSAT 2008. Conductes de salut de la població adolescent de Terrassa. En: Sidastudi.org [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/f1Ouzn

- Encuesta de Salud del País Vasco, 2007. En: Osakidetza [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/GD50HN

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Hábitos de salud en la población juvenil de la Comunidad de Madrid. Año 2008. Bol Epidemiol Com Madrid. 2009;15:3-48.

- Encuesta Estatal sobre Consumo de Drogas entre Estudiantes de Enseñanza Secundaria de 14 a 18 años (ESTUDES), 2011. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2011.

- Díez-Gañán L. Hábitos de salud en la población juvenil de la Comunidad de Madrid 2012. Resultados del sistema de vigilancia de factores de riesgo asociados a enfermedades no transmisibles en población juvenil (SIVFRENT-J). Año 2012. Bol Epidemiol Com Madrid. Madrid: Consejería de Sanidad; 2013. Disponible en http://goo.gl/YDOJeg

- Informe Juventud en España. Madrid, 2012. En: Instituto de la juventud (INJUVE) [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/R8P7j5

- Belza MJ, Koerting A, Suárez M, Álvarez R, López M, Melero I, Royo A. Jóvenes, relaciones sexuales y riesgo de infección por VIH/sida en España 2003. FIPSE [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://fipse.es/sites/default/files/documentos/publicacion/2015/07/20/manual_jovenes.pdf

- Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el SIDA. Encuesta de salud y Hábitos Sexuales. España, 2003. En: Instituto Nacional de Estadística [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/xwImfe

- Estudio sociológico: contexto de la interrupción voluntaria del embarazo en población adolescente y juventud temprana 2006. En: Observatorio de Salud de la Mujer. [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/7hH4Qp

- Informe 2004. Volumen II: prácticas y comportamientos relativos a los hábitos saludables 2004. Madrid: Instituto de Salud Pública de Madrid [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en http://goo.gl/veLiSh

- Salud sexual y reproductiva. Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en www.msssi.gob.es/campannas/campanas06/enlacesSaludsexual.htm

- De Irala J, Osorio A, López-del Burgo C, Belen VA, de Guzman FO, Calatrava M, et al. Relationships, love and sexuality: what the Filipino teens think and feel. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:282.

- Salganicoff A, Wentworth B, Ranji U. Emergency contracepcion in California. Kaiser Family Foundation Survey; 2003. En: Kaiser Family Foundation Social [en línea] [consultado el 08/09/2015]. Disponible en https://goo.gl/k9jsyv

- Lara Hortega F, Heras Sevilla D. Conocimientos y creencias en la primera etapa de la adolescencia. Datos obtenidos en una muestra de 2.º y 3.º de ESO de Burgos. INFAD Rev Psicología. 2008;1:249-58.

- González Hernando C, Sánchez-Crespo Bolaños JR, González Hernando A. Educación integral en sexualidad y anticoncepción para los/las jovenes. Enferm Clin. 2009;19:221-4.

- Rivadeneyra R, Lebo MJ. Association between television-viewing behaviors and adolescent dating role attitudes and behaviors. J Adolesc. 2008;31:291-305.

- Shafii T, Burstein GR. An overview of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15:201-14.