Vol. 16 - Num. 62

Original Papers

Assistance on the first 48 hours after discharge from maternity in Primary Care Practice

M.ª Teresa Asensi Monzóa, Elena Fabregat Ferrerb, M.ª Dolores Gutiérrez Siglerc, Javier Soriano Faurad

aPediatra. CS Serrería1. Valencia. España.

bPediatra. CS Gran Vía. Castellón. España.

cPediatra. CS Nou Molés. Valencia. España.

dPediatra. CS Fuensanta. Valencia. España.

Correspondence: MT Asensi. E-mail: maite.asensi@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Asensi Monzó MT, Fabregat Ferrer E, Gutiérrez Sigler MD, Soriano Faura J. Assistance on the first 48 hours after discharge from maternity in Primary Care Practice. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2014;16:117-24.

Published in Internet: 30-06-2014 - Visits: 21271

Abstract

Introduction: a critical period of time, sometimes too long, passes since healthy term infants are discharged from hospital until they are visited at primary care practices.

Objective: to assess the age after birth when healthy term infants are first checked at primary care practices in Comunitat Valenciana.

Material and methods: survey of primary care pediatricians from Comunitat Valenciana.

Results: Forty-six Primary Care Practices participated in the provinces of Castellón and Valencia (from a total of 162 practices). Data from 248 term infants from April 9th to June 30th 2013 were collected. Fifty-eight percent of the infants were first seen after the fifth day of life. Children born in a public hospital are almost twice as much likely to be visited before 6 days of life than children born in a private hospital (odds ratio [OR]: 1.97, 95% CI: 0.92 to 4.1, p = 0.07). Exclusive breastfeeding and mixed feeding were seen after the fifth day of life in 56.93%. No health insurance card at discharge (most of children born in a private maternity), essential to make an appointment, was observed in 24.2% of the cases studied.

Conclusions: since the time healthy term infants are discharged from hospital until they are first visited by the pediatric-nurse team, a too long critical period passes.

Keywords

● Breastfeeding ● Newborn ● Postnatal visit ● Prevention newbornINTRODUCTION

Spain has a universal and free public health system in which the transition from maternity care to primary care (PC) is not well established and entails an unnecessarily complex administrative process. Access to PC centres (healthcare centres [HCCs]) depends on the accreditation of the newborn (NB) with a public health care card (Tarjeta de Asistencia Sanitaria [TAS]), and on being assigned a paediatrician in the corresponding health care district, two procedures that are not routinely performed at discharge in all maternity units in the Autonomous Community of Valencia. It also requires filing a request for an appointment with the PC paediatrics team, with no apparent protocol or guidelines set up to rush this process and facilitate the timely meeting between the family and the paediatrician, midwife, or nurse.

This is also an issue in other developed countries, such as the United States, where it has been observed that NBs do not receive the recommended postnatal care,1 especially those who are most vulnerable, with lower socioeconomic status. Still, the source of the problem there is probably different, as the United States healthcare system is neither universal nor free.

Hypernatraemic dehydration (HND) in breast fed NBs due to inadequate intake usually requires admission, on average, by the seventh day of life, with a range of 6 to 10 days.2 In our setting, the mean age at admission is of 4.58 days (range: 2-11 days) and the incidence is of 1.4 cases per 1000 birth each year.3 Perhaps admissions happen earlier in Spain due to protective factors such as free healthcare, universal coverage, and easy access to public hospitals.3

Programmes that perform routine weight checks at 72 to 96 hours after birth succeed in the early detection of HND (diagnosis at a mean of 3 days of age, as opposed to 6 days when such checks do not take place), with smaller increases in sodium (147 mmol/L vs 150 mmol/L). Other valuable results obtained in these programmes are the breastfeeding (BF) rates at discharge (73% vs 22%) and at four weeks (57% vs 22%). All these differences were statistically significant according to several studies.3,4

While there is variability between centres, the study by Escobar5 found that visiting the assigned HCC within 72 hours after discharge is a protective factor that reduces the number of NB readmissions to the hospital (adjusted odds ratio [OR] for readmission: 0.83; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.69 – 1.0).

From the perspective of health prevention and promotion as it concerns continuation of exclusive BF until six months of age, the “Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding”6 published by the WHO showed that early support from health services after discharge from the maternity unit resulted in higher rates of BF as reported in assessments at 4 weeks and 6 weeks. Thus, in Brazil, infants who attended lactation centres were more likely to be breastfed exclusively than non-attenders at 4 months (43% versus 18% respectively) and 6 months (15% versus 6%).6

A randomised clinical trial on 100 mothers, divided between an intervention group with a first check-up at day 4 or 5 postpartum and a control group with a first check-up in an outpatient facility after the first week of life, found that 100% of the BF mothers in the intervention group continued to breastfeed exclusively in the second month of life, versus 70% in the control group. The only independent risk factor for BF discontinuation was the check-up at 1 week postpartum (p=0.06) with an OR of 4.1 (95% IC, 1.19 – 14.35)6.

Other studies have shown that the timing of interventions for lactation education and support is crucial. Thus, BF difficulties were observed in 6% of infants that received a home visit on day 3 postpartum, versus 34% of infants that did not (OR, 7.66; 95% CI, 6.03 – 9.71). Those who received support at week 1 (day 7 postpartum) were 11.5 times more likely to have feeding problems than those who had been visited on day 3.7

A randomised clinical trial in 60 mothers seen in a hospital that participates in the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI, an international accreditation of good practises in the management of birth and lactation granted by the WHO and UNICEF) found that receiving additional support at home on day 3 postpartum (intervention group) as opposed to receiving education or standard care a few hours after delivery (control group) resulted in a significant increase in the rate of exclusive BF at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 6 months, as well as greater total duration of BF.8

Based on the existing evidence, several scientific and healthcare institutions support a visit in the first days of life and before the first week ends: the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics [AEPap]) and AEPap’s Group of Health Prevention and Promotion Activities recommended for childhood and adolescence and the Programme of Health Prevention and Promotion Activities of the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine [PAPPS-semFYC])9-16.

“Guía de atención al nacimiento y la lactancia materna para profesionales sanitarios”, the guidelines for clinical practice published by the Committee on Breastfeeding of the Hospital 12 de Octubre and the Primary Care HCCs17, recommends that the administrative staff schedule the first visit of the NB and his or her parents to the HCC whether or not the neonate has the TAS, and that the appointment is set for earlier than day 5 postpartum whenever possible.

Still, the guidelines cannot effect change if they are not applied, so we need to develop strategies for their implementation, involving all healthcare professionals working in any of the HCCs that care for mothers and their children.18

Objective

Learning the age at which NBs first receive care after being discharged from the maternity unit in the Autonomous Community of Valencia, and the relationship of this variable with other variables considered important (whether the TAS was obtained prior to discharge, type of feeding at the time of the first HCC visit, hospital of delivery ...).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We developed a survey using the tools of the Google Drive® environment. The study included healthy NBs discharged from the maternity ward within the first 72 hours postpartum. NBs born by caesarean delivery and admitted to the neonatal unit were excluded. The variables under study were the following: a) age at first PC visit in the HCC; b) hospital of delivery; c) type of feeding at discharge from maternity unit, and d) whether the TAS was obtained prior to discharge from maternity.

The survey was addressed to the population of PC paediatricians in the Autonomous Community of Valencia. Those willing to participate had to access the survey and have it filled out at the time the NB was seen by the nurse, midwife, or paediatrician.

The following protocols were used for the recruitment and collaboration of paediatricians: a) request for collaboration sent to the distribution list of PC paediatricians of the Asociación Valenciana de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Valencian Association of Primary Care Paediatrics, [AvalPap]); b) request for collaboration with the study sent by email to the members of the AValPap; c) request for collaboration with the study sent by email to the members of the Sociedad Valenciana de Pediatría (Valencian Society of Paediatrics).

The study was conducted between April 9 and June 30, 2013.

RESULTS

Out of the total 162 centres in the provinces of Castellon and Valencia (including the auxiliary centres), 48 collaborated providing data on 1 or more NBs seen during the study period. The study included 248 NBs.

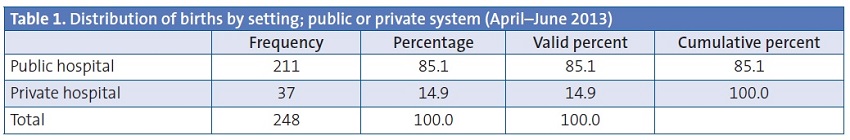

Of all NBs in the study, 14.9% had been delivered in private maternity units (Table 1).

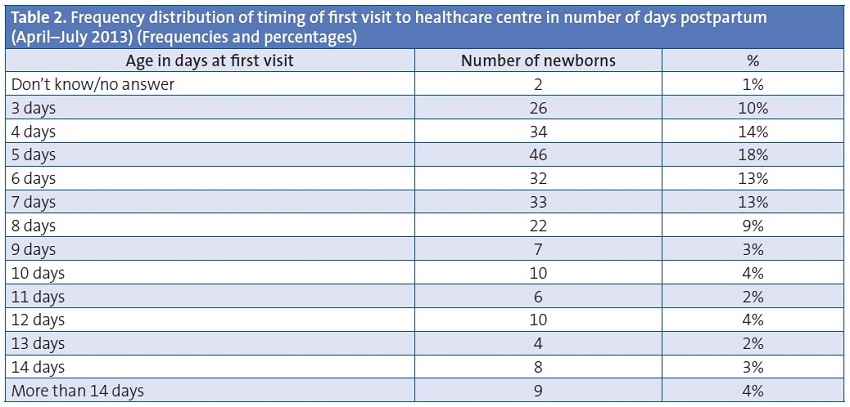

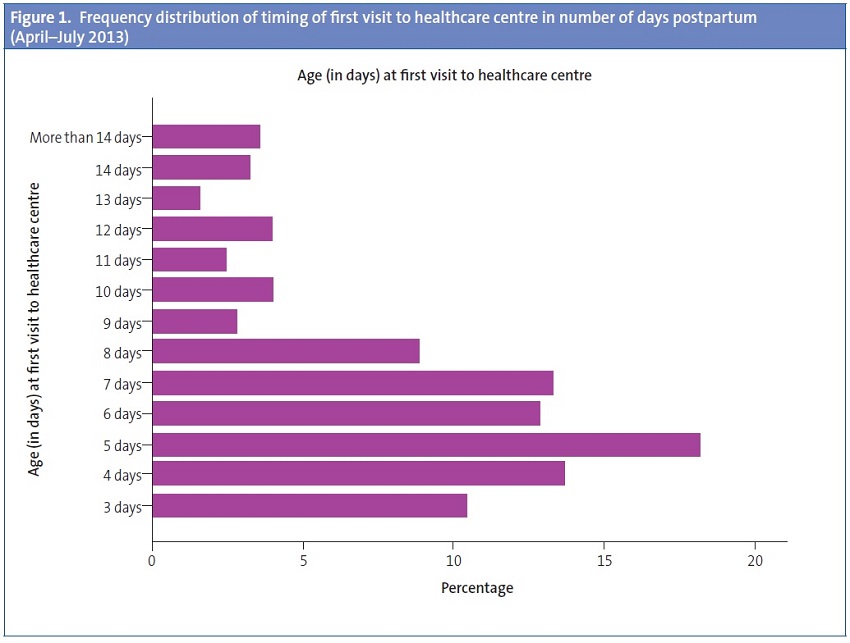

The visits occurred after day 5 postpartum in 58% of NBs, and 15% of NBs had not been seen by either a nurse or a paediatrician in PC by day 10 postpartum (Table 2; Figure 1).

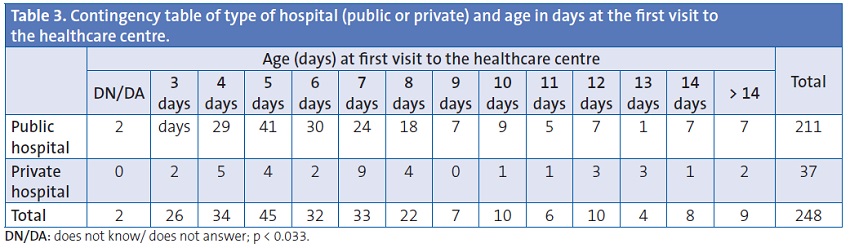

The type of setting at which the NB was delivered, public or private, was associated (p < 0.05) with the delay of the first visit to the HCC (Table 3).

Children born in a public hospital were almost twice as likely (OR, 1.97; 95% CI, 0.92 to 4.1; p = 0.07) to attend a HCC by day 6 postpartum than children born in a private hospital.

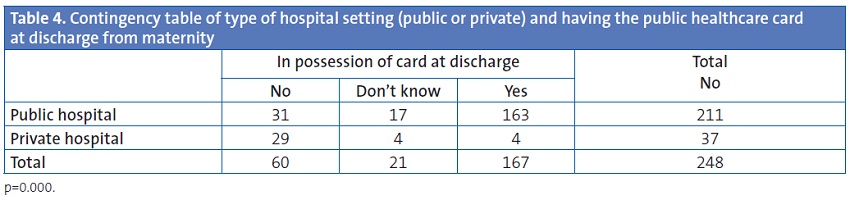

In our study, 24.2% of NBs did not have the TAS at discharge from maternity, when the TAS is necessary to request an appointment at their assigned HCC. Most children born in private maternity units did not get the TAS at discharge. In 19% of maternity units, the TAS was also not provided at discharge, even though the units had the capacity to do it (Table 4).

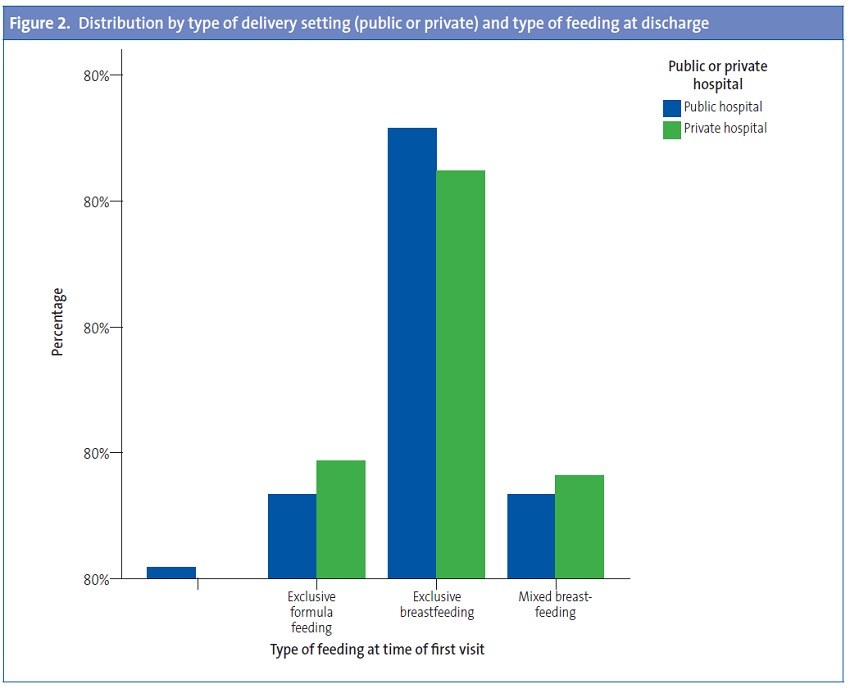

Breastfeeding is an important factor to consider in scheduling the first appointment of the NB within the first 48 hours after discharge from maternity, as it facilitates the correct establishment of BF and prevents the risks of inadequate feeding derived from a lack of support to the mother/child dyad. About 85% of NBs were breastfeeding (exclusively or in combination with formula) at discharge from the maternity unit.

We did not find significant differences in the type of feeding (exclusive BF, mixed BF, exclusive formula feeding) between the different hospitals of delivery. We also found no differences in the type of feeding when we grouped the delivery hospitals into public or private (Fig. 2).

Children born in a public hospital were 1.57 more likely to be exclusively breastfed than children born in a private hospital (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.61 to 4; p = 0.34).

Of all NBs with exclusive or mixed BF, 56.93% had their postnatal visit after day 5 postpartum, which presents various risks: not resolving issues in poorly established BF, discontinuation of BF, dehydration and jaundice due to inadequate intake, and other complications.

DISCUSSION

Limitations of the study: the results are affected by participation bias, and the sample was not obtained by stratification of births, hospitals of delivery, HCCs, and provinces. Despite these limitations, the results provide a fair picture of what is happening in our region, and in the absence of other studies they can be used to assess the magnitude of the issue and its association with the independent variables of the study, and to reach conclusions and develop recommendations to improve neonatal care in PC centres following discharge from the maternity unit.

The time that elapses from the moment the NB is discharged from maternity to the moment that the NB is first seen by the paediatrician is crucial, and at times too prolonged.

In our study, 58% of NBs attended the HCC after day 5 postpartum, and 15% of the children had not been seen by a PC nurse or paediatrician by 10 days postpartum.

The second test for metabolic and genetic disorders has to be done between day 3 and day 5 postpartum, but is often done later. The delay in the first visit makes NBs particularly vulnerable to HND due to poor intake if they are breastfeeding, to pathological jaundice, BF problems that were not previously detected, and hospital readmission, suggesting a flaw in the continuity of care between discharge from the maternity unit and the first visit at the HCC.

The first appointment occurred after day 5 postpartum in 56.93% of NBs with exclusive or mixed BF, which constitutes a risk for poorly established BF, discontinuation of BF, dehydration and jaundice due to inadequate intake, and other complications. From the perspective of health prevention and promotion as it concerns maintenance of exclusive BF through six months after birth, the “Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding” published by the WHO showed that early support from healthcare services after discharge from the maternity unit resulted in higher rates of continued breastfeeding as reported in assessments at 4 weeks and 6 months.6

Access to healthcare services requires that the NB be in possession of the TAS when attending the HCC, that is, that the NB has this card by the time he or she is discharged from the maternity unit.

The TAS had not been provided at discharge from the maternity unit in 24.2% of the NBs under study. Most children born in private institutions did not have the TAS at discharge, even though the TAS is required to request an appointment with the corresponding HCC.

It should be possible to obtain the TAS immediately at the HCC, even with minimum data, so the visit with the nurse, midwife, or paediatrician can happen on the day the family goes to the HCC for the first time.

The data obtained in this study lead us to believe that not all maternity units inform parents of the need to visit the HCC in the first 24-48 hours after discharge; that reception desks at the HCCs do not give the TAS within the day to all NBs, nor consider that their visit to the nurse, midwife, or paediatrician is non-deferrable and to be had on the same day. Otherwise, there would not be nearly 16% of children that do not have their first visit until after their tenth day of life.

Recommendations

- Postnatal care will be given at the PC centre 48 to 72 hours after discharge from the maternity ward.

- The family will be provided with a discharge report describing performed interventions, pending interventions, and proposed plans. The latter will inform the PC Paediatrics team of any care required by the NB in the PC setting.

- Accreditation with the TAS at the time of discharge from the maternity unit.

- Assignation of paediatrician and scheduling of appointment with PC nurse, midwife or paediatrician prior to discharge from the maternity unit.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS: AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria • AValPap: Asociación Valenciana de Pediatría de Atención Primaria • BF: breastfeeding • HCC: healthcare centre • HND: hypernatraemic dehydration • NB: newborn • OR: odds ratio • PC: Primary Care • PrevInfad: Grupo de Actividades Preventivas y de Promoción de la Salud recomendadas para la infancia y la adolescencia de la AEPap y del Programa de Actividades Preventivas y de Promoción de la Salud (PAPPS-semFYC) • TAS: public healthcare card • WHO: World Health Organization • 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Galbraith AA, Egeter SA, Marchi KS, Chavez G, Braveman PA. Newborn early discharge revisited: are California newborns receiving recommended postnatal services? Pediatrics. 2003;111:364-71.

- Oddie S, Richmond S, Coulthard M. Hypernatraemic dehydration and breast feeding: a population study. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:318-20.

- Peñalver O, Gisbert J, Casero J, Bernal A, Oltra M, Tomás M. Deshidratación hipernatrémica asociada a lactancia materna. An Pediatr (Barc). 2004;61:340-3.

- Iyer N, Srinivasan R, Evans K, Ward L, Cheung W, Matthes J. Impact of an early weighing policy on neonatal hypernatraemic dehydtration and breast feeding. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:297-9.

- Escobar G, Greene J, Hulac P, Kincannon E, Bischoff K, Gardner M, et al. Rehospitalisation after birth hospitalisation:patterns among infants of all gestations. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:125-31.

- OMS. Pruebas científicas de los diez pasos hacia una feliz lactancia natural. Ginebra: OMS; 1998. p. 81-98.

- Aksu H, Kücük M, Düzgün G. The effect of postnatal breastfeeding education/support offered at home 3 days after delivery on breastfeeding duration and knowledge: a randomized trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:354-61.

- Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Jimenez V, Leduc N. Randomized trial of postpartum care after hospital discharge. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1074-80.

- Chung M, Raman G. Trikalinos T, Lau J, Ip S. Interventions in Primary Care to promote breastfeeding: An evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:565-82.

- Hagan J, Shaw J, Ducan P (eds.). Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervisions of Infants, Children and Adolescents, 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

- Rourke Baby Record: Evidence-based infant/child health supervision guide. 2006. The College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Canadian Paediatric Society [on line] [consulted on 04/04/2009]. Availabe in: http://www.rourkebabyrecord.ca/default.asp

- Brooke A.Health for all children, 4th ed. Editor: David Hall and David Elliman. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 422.

- Demott K, Bick D, Norman R, Ritchie G, Turnbull N, Adams C, et al. Clinical guidelines and evidence review for post natal care: Routine post natal care of recently delivered women and their babies. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners; 2006.

- Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria. Programa de Salud Infantil. Madrid: Exlibris Ediciones; 2009. p. 624.

- Grupo PrevInfad/PAPPS Infancia y Adolescencia. Guía de actividades preventivas por grupos de edad. In: Recomendaciones PrevInfad/PAPPS [on line] [updated on 15/05/2014; consulted on 04/04/2009]. Available in: www.aepap.org/previnfad/actividades.htm

- Guía de Atención al Nacimiento y la Lactancia Materna para Profesionales Sanitarios. Comité de Lactancia Materna, Hospital 12 de Octubre y centros de salud. Servicio Madrileño de Salud. Madrid; 2011.

- Martín-Iglesias S, del Cura-González I, Sanz-Cuesta T, Arana-Cañedo-Argüelles C, Rumayor-Zarzuelo M, Alvarez de la Riva M. Effectiveness of an implementation strategy for a breastfeeding guideline in Primary Care: cluster randomised trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:144.