Vol. 14 - Num. 55

Original Papers

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder from the point of view of the primary care pediatrician

Amalia Pérez Payáa, A Lizondo Escudera, C García Lópeza, E Silgo Gauchea

aPediatra. CS de Catarroja. Valencia. España.

Correspondence: A. Pérez. E-mail: amperezp@comv.es

Reference of this article: Pérez Payá A., Lizondo Escuder A, García López C, Silgo Gauche E. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder from the point of view of the primary care pediatrician. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2012;14:225-9.

Published in Internet: 19-09-2012 - Visits: 18656

Abstract

Introduction: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common neurobehavorial disorder in children and adolescents. However there are not studies about this condition from the standpoint of the primary care pediatrician.

Material and methods: on July 2011 the patients with the diagnosis of ADHD and between 6 to 12 years of age were selected at the Catarroja Health Center (Valencia). Patient data from the clinical history were recorded and who was the professional that made the diagnosis, treatment and follow up.

Results: forty-seven children were diagnosed of ADHD from a total of 2466 (prevalence rate 1.9%). Most of them were referred from the primary care pediatrician to the pediatric neurologist or psychiatrist. The most common treatment was methylphenidate followed by atomoxetine. Complementary tests were performed in 32% of the patients to rule out alternative causes for the symptoms. The coexisting conditions found were similar to other reports. The outcome of the patients, when reported, was satisfactory in most of them (36%).

Conclusions: the prevalence found in our area is low, probably due to the study design. Patients are diagnosed and treated frequently by the pediatric neurologist or psychiatrist. Some of the cases are treated by the pediatrician, tendency that we hope to be increased.

Keywords

● Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ● Diagnosis ● Prevalence ● Primary care ● TreatmentINTRODUCTION

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neuropsychiatric disorder in childhood and adolescence1. Its presence has serious repercussions on the personal development and the family environment of the patient.

When we reviewed the published research on ADHD, we found various studies devoted to the prevalence of this disorder2,3, as well as guidelines and recommendations for managing patients with this condition4,5, but found no literature with information about the actual reality of these children, the professionals—like us—who treat them, the medications they take, and the evolution of their condition over time.

The Primary Care Paediatrician (PC) is an accessible professional who has an ongoing relationship with the child and his family, and is thus in a privileged position to be involved in the diagnosis and treatment of children with this pathology. However, the diagnosis and clinical management of these patients is a complex task that requires specific training, experience in prescribing and managing medication, and most importantly, to have the necessary time allotted during visits to perform an adequately long interview without rushing. Regardless of these challenges, many PC paediatricians wish to be involved in the treatment of these patients.

This study aims to clarify the current situation of ADHD in our healthcare field. It is an observational study that gathers the relevant epidemiological and clinical data of the patients, providing the basis for a more involved approach by the paediatricians at our healthcare centre (HCC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Catarroja HCC is located in a town of the Horta Sud area near the city of Valencia. Its staff includes four paediatricians, and the centre uses computerised clinical histories. The computer software we employ (Abucasis), provided by the Department of Health of the Valencian Community, uses the ICD-9 classification of diseases diagnostic codes.

Inclusion criteria: as for patient selection, we included children who had a current ADHD-related diagnosis as of 1 July 2011: ICD-9-314 (hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood), ICD-9-314.9 (unspecified hyperkinetic syndrome), ICD-9-314.2 (hyperkinetic conduct disorder), ICD-9-314.00 (attention deficit disorder without mention of hyperactivity) or ICD-9-314.01.

Variables: after selecting patients with these diagnostic codes, we reviewed their clinical histories to gather the following data: date of birth, referrer, date of diagnosis, diagnosing professional, diagnostic tests, presence of comorbidity, whether the patient was receiving psychological support at the time, and how his condition had evolved over time.

We defined the referrer as the person who sought medical attention for the patient: the parents or school (the teacher or the school counselling service); the date of diagnosis, the date on which the ADHD diagnosis first appears in the clinical history; and defined the diagnosing professional as the person who made the diagnosis and prescribed medication or was in charge of monitoring the treatment: neuropaediatrician, child psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or paediatrician. We recorded coexisting conditions as neurological comorbidities or psychiatric comorbidities. As for the evolution of the patient, it was considered good if the history made any reference to an improvement in the patient’s behaviour or his academic achievement.

RESULTS

This study found 47 children diagnosed with the aforementioned codes. We serve 4873 children, out of which 2466 are between 6 and 14 years of age. The latter number is the one that has been used to calculate the prevalence, which is of 1.9%. The ages of the children at the time of diagnosis ranged between 2 and 13 years, with an average of 8 years (standard deviation: 2.5). There were 39 boys and 8 girls.

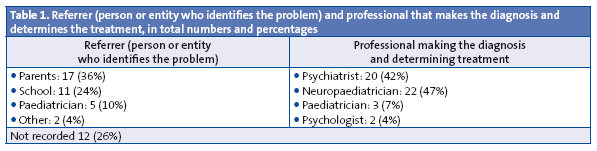

Table 1 shows the referrers and the professionals in total numbers and percentages. There were 12 children (26% of the total) whose clinical histories did not include information regarding the referrer.

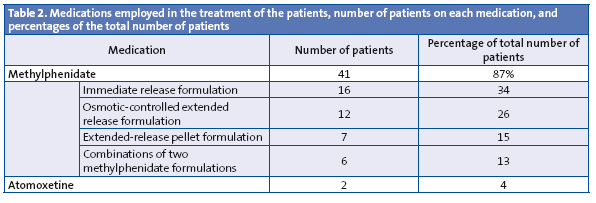

Table 2 shows the pharmacological treatment that was being followed by patients at the time of the last documented visit. Only two of the patients received psychological treatment alone, and the rest was taking medication or had taken it in the past. Several patients had switched medications over the course of their treatment.

Complementary examinations were performed on 15 children (32% of the total). They included eight electroencephalograms, six neurophysiological studies (brain mapping and auditory and visual evoked potentials), two intelligence quotient tests, one nuclear magnetic resonance scan, and one computerised axial tomography brain scan.

Neurological or psychiatric comorbidities were noted in the histories of 23 (49%) of the patients: anxiety in one patient, aggression in two, Tourette’s syndrome in one, enuresis in one, cephalea in one, a language disorder in four, reading and writing disorders in three, epilepsy in three, and academic failure in six. Ten (21%) patients were receiving psychological support: six attended a school counselling office, one was being treated by the psychologist at the childhood mental health centre, two had completed the Cogmed working memory training, and one had received neurofeedback therapy. As for the progress of the children, there was data available for 17 patients (36%): the evolution of ADHD was good in 12 patients, fair in 2, and poor in 3.

DISCUSSION

First of all, we ought to note the lack of data in the study. Since it was retrospective, we could only include whatever data were available in the clinical histories, which in some cases were quite scarce.

For many patients who were diagnosed before the study started, the paediatrician had suspected the diagnosis and, in agreement with the parents, referred the patient to the neuropaediatrician or psychiatrist, who made the final diagnosis. While we are on this subject, we must note that the parents exerted considerable pressure to have the child referred to what they called “a specialist”.

There were also patients who came to the public PC office after they had been diagnosed in a private practise so they could get the prescriptions (at a discounted rate) for the medications prescribed by the original physician. In such cases, the information on the patient is very limited, and including these patients in the study may result in a bias on the reported number of patients receiving medication.

When it comes to prevalence, our study found a rate lower than those reported in the medical literature2. This could be explained by the fact that our study was not designed to research prevalence rates, but instead involved the observation of children who came to the clinic spontaneously.

The ages at diagnosis and the differences in prevalence between the sexes, however, were consistent with those reported in the literature6,7.

When it comes to the professional making the diagnosis, it is almost evenly split between the neuropaediatrician and the child psychiatrist. Our centre has a Childhood Mental Health Unit with which we work very closely, so we frequently refer to the psychiatrist if we do not suspect a neurological disorder that may need to be assessed by the neurologist.

Three patients in the study were diagnosed and treated by the paediatrician himself, reflecting the current trend of having the PC paediatrician diagnose and monitor these patients8.

Most of the medications administered to the patients were various forms of methylphenidate derivatives; atomoxetine was the other medication used for pharmacological treatment, and there were two children who were treated by the clinical psychologist with psychotherapy alone.

Few complementary examinations were performed, in adherence to the current recommendations, which do not advise the systematic performance of complementary examinations9, unless indicated by findings in the patient’s history or physical examination. Some of the performed neurophysiological examinations had not been requested by us, so we assume that they were part of the diagnostic approach of the specialists involved.

The coexisting conditions we found were similar to those recorded in the literature10, with school failure and anomalies in language, reading, and writing as the most common disorders. Concomitant epilepsy was present in three of the patients, of which two were receiving medication to treat their ADHD, since such treatment is not contraindicated.

Psychological treatment in addition to pharmacological treatment and school counselling services is recorded in the clinical histories of only a few patients (21%). This result is probably due to gaps in clinical history taking, and such treatment may have been in place in more cases.

Last of all, the evolution of the patients, at least in the short-term, has been favourable in most cases. Once again we face a lack of data, since patient progress is recorded in few histories.

CONCLUSIONS

In our healthcare area, ADHD is diagnosed and treated by a variety of professionals. As paediatricians, we are becoming increasingly involved in its diagnosis and monitoring. The characteristics of the patients seem to fit the epidemiology data referred to above; the treatments administered and the progress of the patients also seemed consisted with those reported in the literature we reviewed.

The main problem we identified in our study was the lack of data in some of the clinical histories.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they had no conflicts of interest in relation to the preparation and publication of this paper.

ACRONYMS: PC: Primary Care • HCC: healthcare centre • ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

BIBLIOGRAFHY

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV TR. Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales-IV. Texto revisado. Barcelona: Masson; 2001.

- Cardo E, Servera M, Llobera J. Estimation of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among the standard population on the island of Majorca. Rev Neurol. 2007;44:10-4.

- Rodríguez Molinero L, López JA, Garrido M, Sacristán AM, Martínez MT. Estudio psicométrico-clínico de prevalencia y comorbilidad del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad en Castilla y León (España). Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2009;11:251-70.

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH) en Niños y Adolescentes. Fundació Sant Joan de Déu, coordinador. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre el trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH) en Niños y Adolescentes. Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad. Agència d’Informació, Avaluació i Qualitat (AIAQS) de Cataluña, 2010. Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS. AATRM Nº 2007/18.

- Rubió Badía J, Mena Pujol B, Murillo Abril B. El pediatra y la familia de un niño con TDAH. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2006;8 Supl 4:S199-216.

- Criado Alvarez JJ, Romo Barrientos C. Variability and tendencies in the consumption of methylphenidate in Spain. An estimation of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Rev Neurol. 2003;37(9):806-10.

- Boneti M, Clavenne A. The epidemiology of psychotropic drug use in children and adolescents. Int Rev Psichiatry. 2005;17(3)181-8.

- Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and and Management. ADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007-22.

- Subcommitee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practical guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1158-70.

- Jensen PS, Martin D, Cantwell DP. Comorbidity in ADHD: implications for research, practice and DSM-V. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1065-86.