Mood of adolescents and its relation to risk behaviors and other variables

Marta Esther Vázquez Fernándeza, M.ª Fe Muñoz Morenob, Ana Fierro Urturic, M Alfaro Gonzálezd, L Molinero Rodrígueze, P Bustamante Marcosf

aPediatra. CS Arturo Eyries. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

bUnidad de Investigación Biomédica. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Valladolid. España.

cPediatra. CS Pisuerga. Arroyo de la Encomienda. Valladolid. España.

dServicio de Pediatra. Hospital de Medina del Campo. Medina del Campo. Valladolid. España.

ePediatra. CS Casa del Barco. Valladolid. España.

fMIR-MFyC. CS Arturo Eyries. Valladolid. España.

Correspondence: ME Vázquez. E-mail: mvmarvazfer@gmail.com

Reference of this article: Vázquez Fernández ME, Muñoz Moreno MF, Fierro Urturi A, Alfaro González M, Molinero Rodríguez L, Bustamante Marcos P. Mood of adolescents and its relation to risk behaviors and other variables. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2013;15:219.e75-e84.

Published in Internet: 04-09-2013 - Visits: 23986

Abstract

Introduction: adolescence is a stage of life where new mental abilities are developed and allow adolescents to build their own ideas and adopt different lifestyles. In this paper mood states and related factors are described.

Methods: we surveyed a sample of 2,412 schoolchildren aged 13 to 18 years old in the province of Valladolid, studying 2nd, 3rd and 4th year of Secondary Education (ESO) and 1st and 2nd of High School. Six aspects of mood state were considered to be classified as positive or negative. The association between negative mood states and sociodemographic and economic factors and risk behaviors were analyzed using a logistic regression model.

Results: the frequency of negative mood states was 14.9%, being higher in females 16.9% (OR: 1.63; IC 95%: 1.23-2.15; p=.001) and those studying second high school 20.7% (OR: 1.95; IC 95%: 1.29-2.97; p=.002).

An association has been found between negative mental states and having different family situations, such as not living with both parents and/or brothers and not working neither the father nor the mother. This is also related to having worse grades than the average, being overwhelmed by not having Internet connection, frequently accessing to sexual content, stealing, feeling physical or psychologically mistreated, having suffered of sexual harassment or being overweight. Protective factors were having brothers or sisters, being statistically significant having two or more.

Conclusions: the prevalence of mental health problems in adolescents has proved similar to what has been previously published and is lower in females. Several sociodemographic and economic variables and risk behaviors are associated with negative mood states. The assessment of these aspects at the doctor’s office can be useful for detecting adolescents at risk.

Keywords

● Adolescent ● Mood states ● Risk behaviors ● Socioeconomic factorsINTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a critical stage in life because it is when certain risk behaviours start. Physical and hormonal changes, along with social transformations, are among the determining factors1,2. To monitor such behaviours, which have repercussions on health, we perform routine surveys that facilitate the gathering of valid data3.

Although in many cases mental health (developmental, mood, or behaviour-related) is not recognised as a health problem requiring medical attention, the adolescent is particularly susceptible to these problems4,5. There are studies that have identified demographic or economic factors, or family situations where there is not enough affection or lacking stable adult role models that may influence the mood of adolescents6,7. Furthermore, these factors may play a role in substance use, sexual behaviours, diet, physical activity, experiencing harassment, and violent behaviours8,9. However, this relationship is complex and the studies devoted to it are scarce. As paediatricians and family physicians who serve adolescents we cannot disregard these factors, as they influence health, wellbeing, and risk behaviours. It is important that we assist teenagers in learning adaptive psychological skills so they can engage in fulfilling relationships and care for their health1.

This article shows the results obtained in a study of habits and behaviours associated to health conducted on a sample of schoolchildren aged 13 to 18 years in the province of Valladolid between March and May of 2012, for which we collected data regarding the mood states of the students. The main purpose of this study was to describe the mood of these adolescents. The secondary goals were assessing for the association between mood and several socio-demographic variables and risk habits, attitudes, and behaviours.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

We did a descriptive cross-sectional study. The population under study consisted of adolescents 13 to 18 years of age in the province of Valladolid (Spain) enrolled in schools offering the second, third, and fourth year of compulsory secondary schooling, or ESO, and first and second year of post-compulsory schooling, or Bachillerato, established by the LOGSE education reform law.

The total number of students, calculated from the records of the Department of Education, the FERE (Spanish Federation of Religious Educators), and the private schools of Valladolid, was 18,888.

The students for the study were selected by means of multi-stage cluster sampling, selecting schools at random in the first stage (n=14), and classrooms in the second stage. All students in the selected classrooms were included in the study.

The sample size was calculated for an estimated proportion of 50% and a 2.5% accuracy level in a two tail test, assuming a 10% non-response rate, which resulted in 1566 students. The final number of students in the survey, after cleaning the data and excluding questionnaires that were not filled out completely, was of 2412 enrolled adolescents 13 to 18 years of age, so the sample met and exceeded the established minimum sample size.

We telephoned or mailed the administrators of each school to inform them of the objectives and contents of the study, and scheduled one or several days (avoiding those that followed a holiday) to carry out the survey between March and May of 2012. Three schools refused to participate and gave no clear reason for it. The schools notified the families of the students that the latter were going to be asked to participate in the survey, stating that they had the option to refuse participation without consequences.

The research team was in charge of administering the survey. 69% of the sample took the computer-assisted survey, and the rest took it in paper format, since not enough computers were available in the schools’ computer rooms. The electronic data were stored automatically in the database, and the data gathered on paper were manually introduced in the same database.

The selected students filled out the questionnaires personally, and had been informed previously of the confidentiality of the data and of the need to abstain from communicating with each other. Taking the survey was voluntary, and it was done during regular school hours. The time spent to fill it out was of 35-40 minutes. The study design was approved by the Comisión de Investigación de la Gerencia de Atención Primaria (Research Committee for Primary Care Management) of the Western Area of Valladolid.

Data gathering

The questionnaire included, among others, questions pertaining to the adolescents’ moods, questions about socio-demographic variables, academic achievement (grades, having been held back one or more years), leisure (watching television, surfing the Internet), accidents, tobacco (having smoked before, or smoking daily), alcohol (having tried alcohol, or having been inebriated more than twice in the past 12 months), drugs (having tried drugs, or daily consumption of cannabis), antisocial behaviour (skipping class or stealing things), relationships with other people and experiences of abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and bullying behaviours), diet (daily intake of fruit and above-average body weight) and sexual behaviour (sexual relations with penetration and use of the morning-after pill), based on the guidelines of programmes at the international10,11, national12,13, regional and provincial levels14-18.

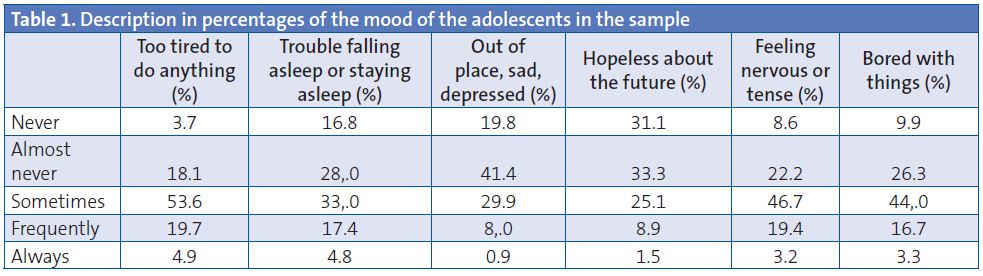

Following the model by Ahonen et al.8, we considered six mood states: a) feeling tired; b) difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep; c) feeling out of place, sad, or depressed; d) feeling hopeless toward the future; e) feeling nervous or tense, and f) feeling bored.

The response categories on the Likert scale were: never, almost never, sometimes, frequently, and always. We considered a mood state was negative when the response was always or frequently in three or more of the six items, following the Catalonian working model, the Barcelona FRESC report14, which in turn was an adaptation of the nationwide HBSC study13.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables are shown with the measures of central tendency and the 95% confidence (CI 95%) and the qualitative variables are represented by means of their frequency distribution.

We used Pearson’s chi-square test to analyse the association between mood, socio-demographic characteristics, and risk factors. In cases where the number of cells with expected values below 5 was greater than 20%, we used Fisher’s exact test or the likelihood-ratio test for variables with more than two categories.

The variables that were significant at the 0.1 level in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in a multivariate model adjusted for confounding variables.

We analysed the data with the statistical package SPSS® version 19.0 for Windows®. Values with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In total, we obtained 2412 validated surveys for adolescents aged 13 to 18 years in the province of Valladolid (Spain).

The mood state items can bee seen in Table 1. The one that stood out most was being too tired to do things always or frequently, reported by 24.6%, followed by feeling nervous or tense (22.6%), and having trouble falling asleep or staying asleep (22.2%).

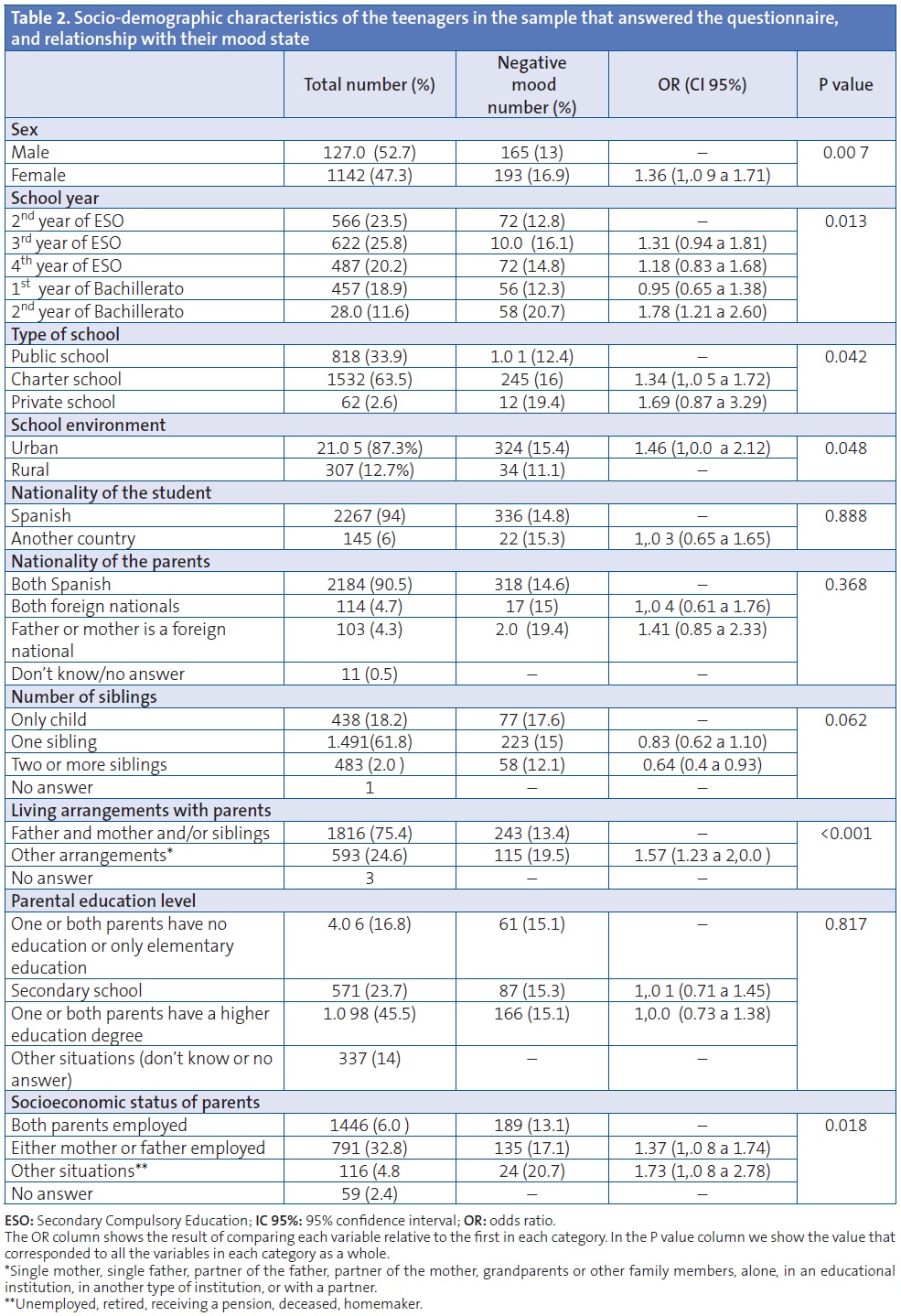

Overall, the prevalence of negative mood states, understood as answering “always‚ or “frequently‚ for three or more of the mood state items under consideration, was 14.9%. Table 2 summarises the main results of mood states in relation to the socio-demographic variables of the adolescent population under study. The bivariate analysis of the different socio-demographic factors and mood showed statistically significant differences for sex, school year, type of school, school environment, type of household structure, and parents’ employment outside the house.

The proportion of girls that reported feeling three or more of the mood disturbances was 16.9% (odds ratio [OR]: 1.36; CI 95%: 1.09-1.71). Students in the second year of Bachillerato reported the greatest number of mood disturbances, 20.7% (OR: 1.78; CI 95%: 1.22-2.60, with the ESO second year students as a reference). Attending a private school and schools set in an urban environment were associated to higher prevalence of negative mood states, and these differences were statistically significant (p=0.042 and p=0.048, respectively). In contrast, socio-economic factors relating to the parents, such as both parents being employed and the household structure conforming to the most frequent type consisting of father, mother, and/or siblings, surfaced as factors that decrease the risk of negative mood states. Yet another factor associated to negative mood states was being an only child, as opposed to having one, two, or more siblings. We found no association with the nationality of the parents or the student, nor with parental education level.

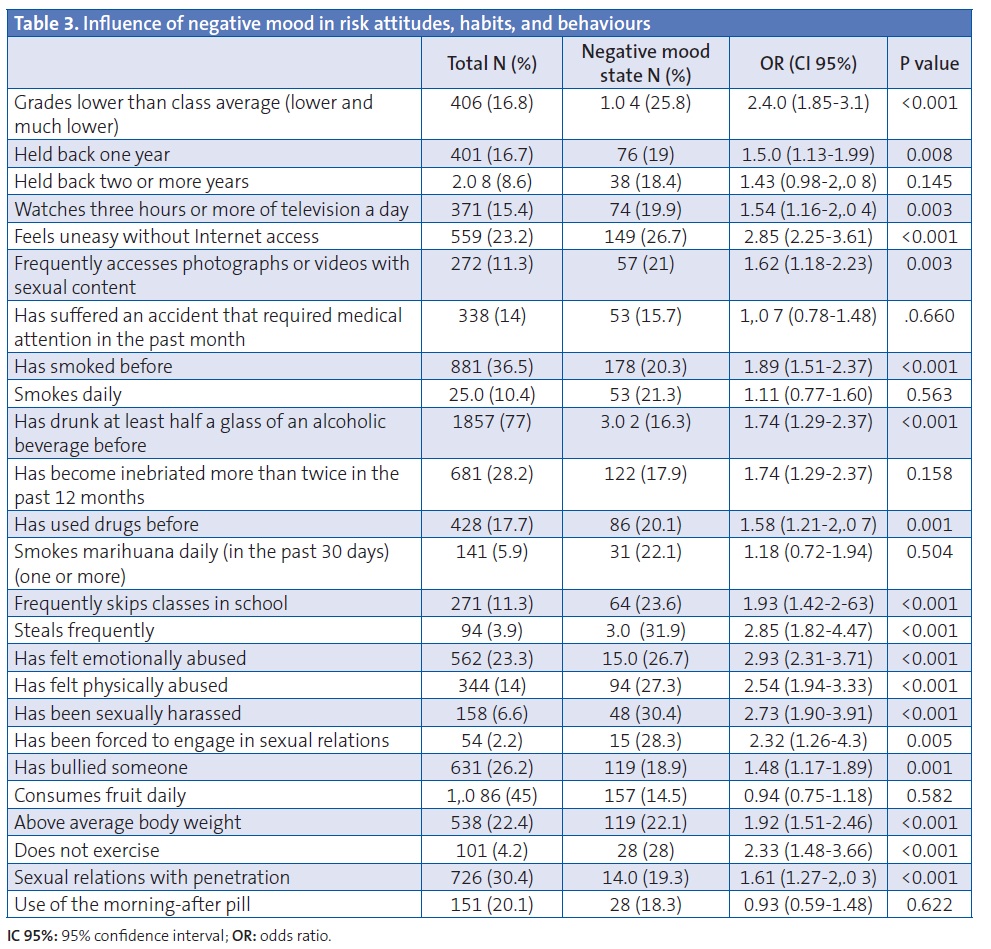

Table 3 summarises the frequency of risk habits, behaviours, and attitudes in the surveyed adolescents, as well as the bivariate analysis of the association of these factors with negative mood states. Thus, we found a statistically significant relationship and an OR above 1 for most of the risk variables. However, we found no relationship with being held back two or more years in school, having been in an accident, smoking daily, getting drunk frequently, daily use of cannabis, daily consumption of fruit, and using the morning-after pill.

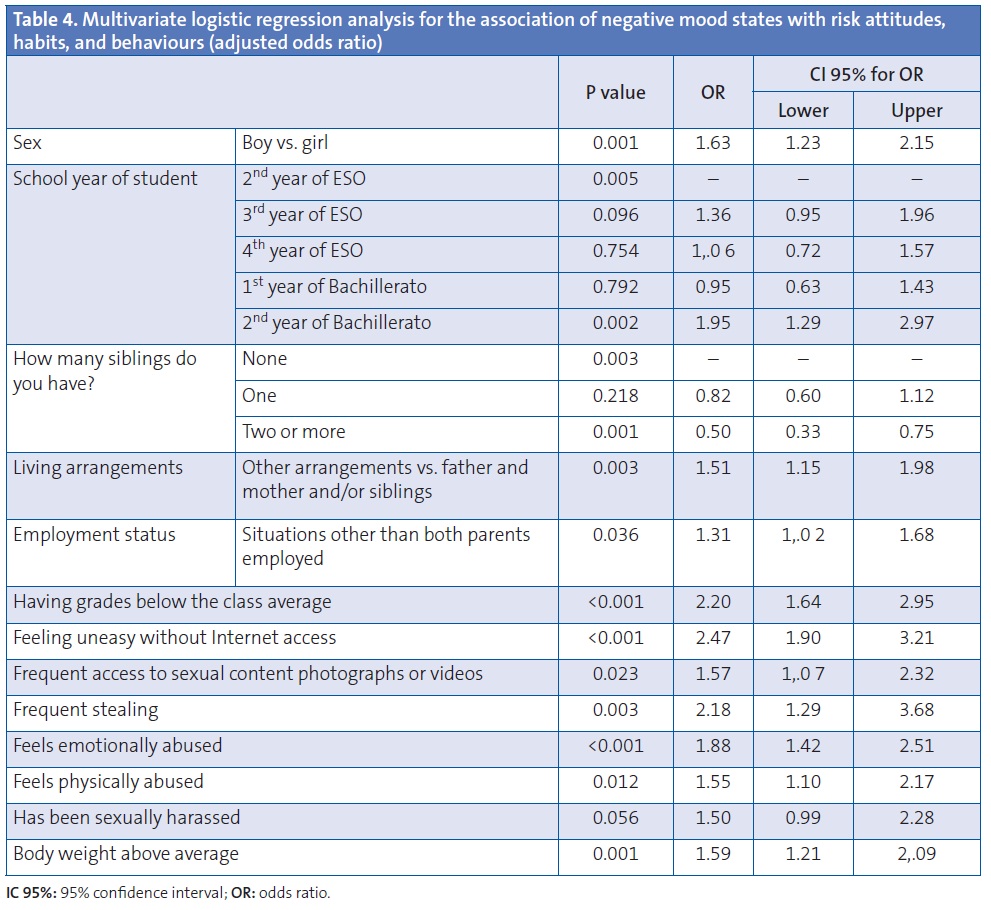

The adjusted odds ratio results of the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 4), showed that the risk of negative mood states increased with female sex, being a second year student of Bachillerato, having household arrangements that differed from living with the mother, father, and/or siblings, situations in which both parents are unemployed, having below-average grades, internet dependency and frequent access to photographs or videos with sexual content, frequent stealing, perceived physical or emotional abuse, having been sexually harassed, or above-average body weight.

We found that having siblings was a protective factor, one that was statistically significant for two or more siblings.

DISCUSSION

Although mental health is not synonymous with mood, the literature often refers to diseases as anxiety and depression6 as triggers for risk behaviours. This kind of survey of the mood states of adolescents has been applied successfully before in other studies7,8. Our study is an attempt to complement and corroborate the results obtained by other authors.

As for the study’s limitations, we ought to note that this is a cross-sectional study in which we evaluate mood states as negative or positive in a given moment. There is a high probability for people experiencing mood fluctuations across time, more so adolescents, who undergo sudden and extreme mood shifts1. Nevertheless, the Likert scale, which includes the items “never‚, “almost never‚, “sometimes‚, “frequently‚ and “always‚, tries to differentiate between passing and long-lasting states.

The prevalence of mental health disorders in European youth ages 15-24 years has been estimated to be around 20%. Ten to twenty percent of Spanish youth may have a mental health problem19. Our work shows a similar prevalence of negative mood states (14.9%) among adolescents 13 to 18 years old.

Being female and increasing age have been associated to negative mood states in adolescence in several studies8. Ahonen et al. reports a 21% prevalence in girls, higher than the one found in our study (16.9%), and values similar to ours for boys (around 13%). These factors are also associated to anxious and depressive states6 and “poor mental health‚ status12.

When it came to socioeconomic factors, previous studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with mental illness. However, it is not clear which of those factors have the most influence on mental health20. Furthermore, to accurately assess the purchasing power of adolescents is a complicated process, as they are often unaware of their parents’ job category or education level. In this study we found an association between negative mood states and private schools, urban environments, unusual or non-traditional households (living with a single mother, single father, father’s partner, mother’s partner, grandparents or other family members, alone, in an educational centre, in an institution, or with a partner), situations in which one or both parents do not have paid work, or to a lesser degree being an only child. Having two or more siblings was a protective factor associated to positive mood states. While in the McLaughlin study parental education was associated with a lower risk for anxiety disorders20, this factor did not seem to influence mood problems in our study, which also showed no association between mood and the nationality of the parents or students.

Risk behaviours in adolescents involve a very complex and multi-factorial process with various elements at play. The greater the number of factors, the higher the risk21; previous studies have demonstrated the relationship between certain sexual behaviours22, diet and exercise23, violence24, and school bullying9, with specific mental health statuses. Some of them have established a relationship between depression and consumption of tobacco25 and drugs26.

We selected the highest-risk behaviours and analysed the probability that they are associated to or facilitated by mood. Most risk habits or behaviours are associated to a negative mood state. But we must highlight that having experienced things such as being held back a year in school more than once, or having habits such as smoking, consuming cannabis daily, or getting drunk frequently, were not greatly associated to negative mood states in adolescents. It seems that the most established and dangerous risk behaviours are associated with adolescents that have more positive mood states, while the testing or middle-ground behaviours, such as being held back a year just once, or smoking and drinking occasionally, occur more often during negative mood states, which then could be setting the stage for the establishment of these habits. This was not the case when it came to having lower grades than average, Internet dependency with access to sexual contents, antisocial behaviours such as skipping classes and stealing, having an above-average body weight, and perceived abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual), which showed a clear association with mood disorders.

Conclusions

- We found frequencies for negative mood states that were similar for the male teenage population, and slightly lower for the female population, compared to other studies.

- The prevalence of negative mood states increased as age increased.

- Mental health problems were associated to several socio-demographic and economic variables.

- Certain habits and risk behaviours were associated to negative mood states.

- Healthcare professionals must be on the watch for and recognise mental health problems. Assessing for them during office visits by taking a proper clinical history in an atmosphere of trust and confidentiality may help identify adolescents who are at risk for developing, or who have already developed, unhealthy lifestyles, with the purpose of referring them to specific preventative programmes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank the schools (administrators, teachers, advisors, and students) for their collaboration in performing the survey. Also, the group Educación para la Salud (Education for Health) of the AEPap (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics) for their interest and help in carrying out the project. We would like to thank the management of the AEPap for trusting us with and helping us fund the project.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interests when it came to preparing and publishing this paper.

FUNDING SOURCE

This study has been funded by the AEPap.

ABBREVIATIONS: AEPap: Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (Spanish Association of Primary Care Paediatrics) • ESO: Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria (Compulsory Secondary Education) • CI 95%: 95% confidence interval • OR:odds ratio.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ruiz Lázaro PJ. Promoviendo la adaptación saludable de nuestros adolescentes. Proyecto de promoción de la salud mental para adolescentes y padres de adolescentes. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2004 [on line] [accessed 09/11/2012]. Available on http://bit.ly/VXRRr2

- Hidalgo Vicario MI, Júdez Gutiérrez J. Adolescencia de alto riesgo. Consumo de drogas y conductas delictivas. Pediatr Integral. 2007;11:895-910.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behaviours Surveillence System; 2004 [on line]. Available on www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5312a1.htm

- Terry PC, Lane AM, Lane HJ, Keohane L. Development and validation of a mood measure for adolescents. J Sports Sci. 1999:17(11):861-72.

- Ras Vidal E, Briones Carcedo O. Los trastornos de ánimo en los adolescentes de un centro de atención primaria. Aten Primaria. 2004;34:565.

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:760-5.

- Monteagudo M, Rodriguez-Blanco T, Pueyo MA, Zabaleta-Del-Olmo E, Mercader M, García J, et al. Gender differences in negative mood states in secondary school students: health survey in Catalonia (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2012;28. [Epub ahead of print].

- Ahonen E, Nebot M, Giménez E. Estados de ánimo negativos y los factores relacionados en una muestra de adolescentes de enseñanza secundaria de Barcelona (España). Gac Sanit. 2007;21:43-52.

- García Continente X, Pérez Giménez A, Nebot Adell M. Factores relacionados con el acoso escolar (bullying) en los adolescentes de Barcelona (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2010;24:103-8.

- Brooks F, Van der Sluijs W, Klemera E, Morgan A, Magnusson J, Gabhainn SC, et al. Young People’s Health in Great Britain and Ireland. Findings from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. HBSC International Coordinating Centre. University of Edinburgh; 2006.

- University of California. Adolescent Questionnaire. California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2010 [on line]. Disponible en www.chis.ucla.edu

- Encuesta nacional de salud de España. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad; 2006 [en línea]. Available on www.msps.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuesta2006.htm

- Moreno-Rodríguez C, Muñoz Tinoco V, Pérez Moreno PJ, Sánchez Queija I, Granado Alcon MC, Ramos Valverde P, et al. Desarrollo adolescente y salud. Resultados del estudio HBSC 2006 con chicos y chicas españoles de 11-17 años. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2008 [on line]. Available on www.hbsc.es/castellano/inicio.html

- Nebot M, Pérez A, García-Continente X, Ariza C, Espelt A, Pasarín M, et al. Informe FRESC 2008. Resultats principals. Barcelona: Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona; 2010.

- Encuesta de Salud Infantil en Asturias. Dirección General de Salud Pública y Participación de la Consejería de Salud y Servicios Sanitarios del Principado de Asturias. Observatorio de la Infancia y la Adolescencia del Principado de Asturias; 2009 [on line]. Available on www.observatoriodelainfanciadeasturias.es

- Schiaffino A, Moncada A, Martín A. Estudi EMCSAT 2008. Conductes de salut de la població adolescent de Terrassa, 1993-2008. Terrassa: Ajuntament de Terrassa; 2009 [on line] [accessed 09/11/2012]. Available on www.terrassa.cat/files/319-5110-fitxer/informe_definitiu-salut.pdf?download=1

- Encuesta de Salud del País Vasco, 2007. Vitoria: Gobierno Vasco; 2008 [on line] [accessed 09/11/2012]. Available on http://bit.ly/VXRAo0

- Servicio de Epidemiología. Hábitos de salud en la población juvenil de la Comunidad de Madrid. Año 2008. Bol Epidemiol Comunidad Madrid. 2009;15(2):3-48 [on line] [accessed 09/11/2012]. Available on http://bit.ly/VXRfSm

- Hernán M, Fernández A, Ramos M. La salud en los jóvenes. Gac Sanit. 2004;18(Supl 1).

- McLaughlin KA, Costello EJ, Leblanc W, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Disorders. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1742-50.

- Igra V, Irwin Jr CE. Theories of adolescent risk-taking behavior. In: Diclemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE (eds.). Handbook of adolescent health risk behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1996.

- Brooks TL, Harris SK, Trall JS, Woods ER. Association of adolescent risk behaviours with mental health symptoms in high school students. J Adolescent Health. 2002;14:280-5.

- Hassmen P, Koivulu N, Uutela A. Physical exercise and psychological well-being: a population study in Finland. Prev Med. 2000;30:17-25.

- Karnik NS, McMullin MA, Steiner H. Disruptive behaviors: conduct and oppositional disorders in adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2006;17:97-114.

- Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wargner EF. Cigarrette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1602-10.

- Ceballos Rivera JJ, Ochoa Muñoz J, Cortez Pérez E. Depression in the adolescent. Its relationship with sports activities and drug consumption. Rev Med. 2000;38:371-9.

Comments

This article has no comments yet.