Vol. 15 - Num. 58

Original Papers

The presence of depressive symptoms in adolescents is the last school year

Catarina Resendea, Alzira Ferrãob

aResidente de Pediatría. Servicio de Pediatría, Centro Hospitalario Tondela-Viseu. Viseu. Portugal.

bAsistente Hospitalario de Pediatría. Servicio de Pediatría, Centro Hospitalario Tondela-Viseu. Viseu. Portugal.

Correspondence: C Resende. E-mail: resende_cat@hotmail.com

Reference of this article: Resende C, Ferrão A. The presence of depressive symptoms in adolescents is the last school year. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2013;15:127-33.

Published in Internet: 21-06-2013 - Visits: 13571

Abstract

Introduction: adolescence is a period of great change, with depressive symptoms being common at this stage of development. There has been an increase in the number of adolescents with depressive symptoms in recent years. One of the instruments used in the detection of depressive symptoms is the Beck Depression Inventory.

Material and methods: observational study, based on self-application of the 2nd version of the Beck Depression Inventory to students of the 12th year of schooling in the academic year 2010/2011.

Results: our survey was administered to 117 students. Adolescents had a mean age of 16.9 years. After the global assessment, we verified that 9.4% of adolescents had some degree of depressive symptoms and 6 of these had severe depressive symptoms. Females were more prevalent in the group of adolescents with overall scores above 13. The average rates of depression were higher in females (9.03 vs. 4.1). The analysis of depressive symptoms alone showed that a decreased ability to work is the most frequent depressive symptom (36%). Five teenagers responded affirmatively to the question "I'd like to kill me."

Conclusion: the mean total scores obtained are slightly lower than those found in other studies, but the percentage of students with severe depressive symptoms is identical to other series (5%). As described in the literature females are the most affected.

Keywords

● Adolescent ● Beck Depression Inventory ● Depressive symptomsINTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a highly relevant period in the development of the individual, and depressive symptoms are quite common during this stage. The estimated prevalence of depression among adolescents is about 4-8%1-3. In the past few years we have seen an increase in the number of adolescents with symptoms of depression2,3.

One of the most widely used instruments to detect depressive symptoms is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). This inventory (BDI) was developed by Beck and his collaborators (Ward, Mendelson, Mock, and Erbaugh, 1961) and consists of a self-report questionnaire with 21 multiple-choice items4-6. Due to its positive psychometric properties, it has become one of the most widely used and valid instruments to evaluate the intensity of depressive symptoms7. This assessment tool has gained a prominent role in the clinical field, as it allows for the evaluation of subjective feelings and the self-image. These are important aspects that contribute to the formal diagnosis of depression5,7. The BDI underwent a considerable revision that led to a second edition (BDI-II) that sought to be more consistent with the diagnostic criteria for major depression as described in the DSM-IV. This second edition (Beck et al., 1996) is used to measure the severity of depression in both psychiatric patients and subjects of the general population over 13 years of age8.

The questionnaire consists of 21 items, rated from 0 to 3 points according to the severity of the symptoms. The total score allows for the differentiation of four categories: from 0 to 13, showing no symptoms or minimal symptoms; from 14 to 19, showing mild depressive symptoms; from 20 to 28, showing moderate depressive symptoms, and with a score greater than 29 indicating severe depressive symptoms6-8.

Depression can be thought of as having two components, the affective component (mood) and the physical component (somatic symptoms). The BDI-II reflects this approach, as it can be separated into two subscales9.

Thus, the affective subscale consists of eight items that include pessimism, past failure, feelings of guilt, feelings of being punished, self-dislike, feelings of worthlessness, self-criticism, and suicidal ideation or wishes. The somatic subscale includes the following items: sadness, changes in appetite, loss of pleasure, loss of interest, crying, agitation, fatigue, indecisiveness, loss of energy, changes in sleeping patterns, irritability, and decreased libido. Still, these two factors of depression are highly interrelated8,9. In this scale, as occurs in any other self-reported scales, the results may be inflated or downplayed by the responding individual.

The purpose of this work was to assess the presence of depressive symptoms in a non-clinical population of 12th-year students in the largest secondary school of the city of Viseu (Portugal).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is an observational analytical study, based on the self-administration of the second edition of the BDI. The set of subjects included every student enrolled in the 12th grade of a secondary school in Viseu, Portugal, during the 2010/2011 academic year.

After addressing a request to the Board of Directors of the academic institution to authorise the administration of the BDI-II, the class teachers of each class devoted the necessary time to explain the questionnaire and have the students fill it out. The study was done in conformance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the consent of the guardians of the adolescents and the management of the school where the questionnaires were administered. We emphasised that participation was voluntary, that questionnaires were anonymous, that there were no right or wrong answers, and that it was crucial that no item be left unanswered.

The collected information was entered in a Microsoft Excel® 2007 database.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was administered to 117 students, out of who 52% (N=61) were female and 48% (N=56) were male. The average age of the subjects was of 16.9 years, ranging from 16 to 20 years.

After scoring all the questionnaires, we found that 9.4% of the surveyed adolescents presented some degree of depressive symptoms, and that 6 of them (5%) presented severe depressive symptoms (Fig. 1).

When we compared both sexes, we saw that the group of adolescents that had no depressive symptoms showed no difference between sexes, while the female sex predominated in the group of adolescents with scores above 13 (9 versus 2). The average total score was 6.4, and the range was 0 to 54. The average scores for depression were higher among female students (9.03 as opposed to 4.1 in males) (Fig. 2).

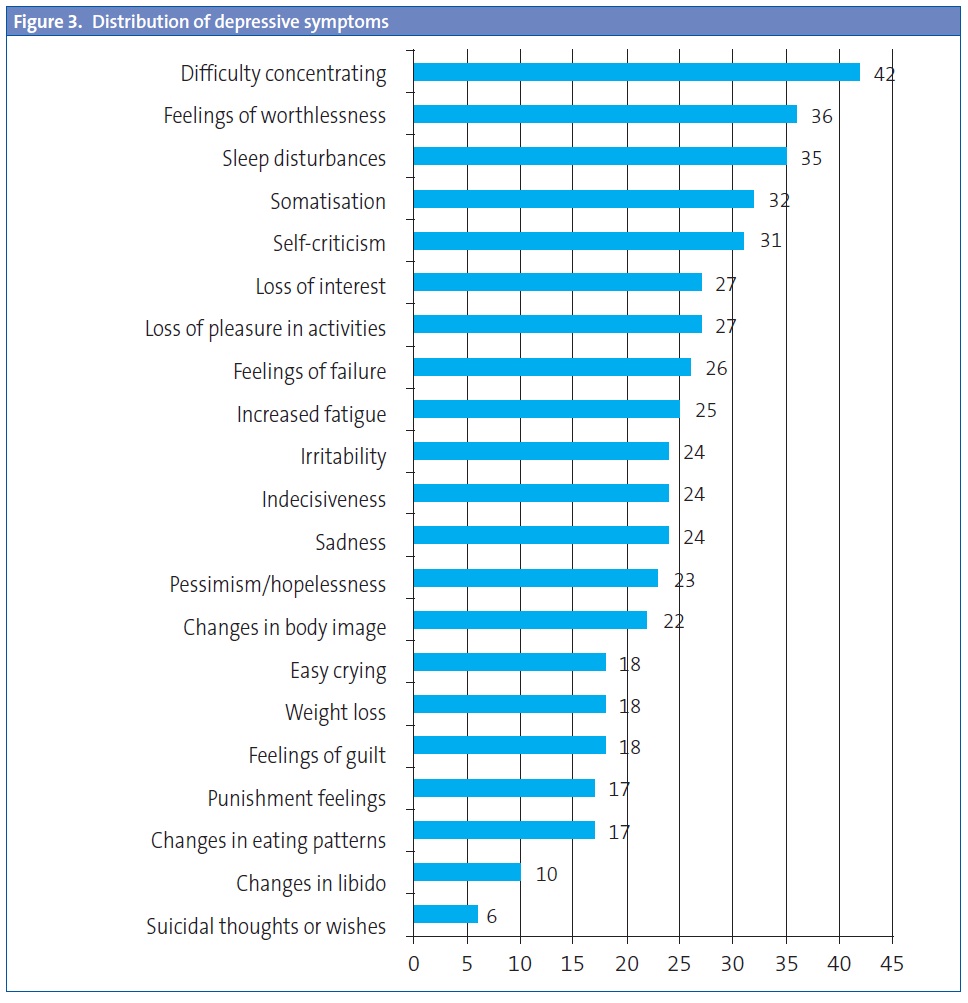

The individual analysis of each of the depressive symptoms (Fig. 3) showed that 20.5% of the adolescents presented some degree of sadness, with 18 (15.4%) reporting crying easily and six adolescents reporting hopelessness regarding the future, while 19.6% of adolescents expressed some pessimism about the future. Twenty-six adolescents had feelings of failure, and 3.4% felt like a complete failure. We saw that 15.4% of the youth had feelings of guilt and that 30.7% reported feelings of self-dislike. The loss of pleasure in daily activities was found in 27 youths (23%). Ten adolescents presented changes in their libido, reporting a dwindling interest in sex.

When it came to indecisiveness, we saw that 20.5% (24 adolescents) reported a decrease in their ability to make decisions. Changes in sleep patterns were found in 30% of the adolescents (35). Similarly, 21.4% reported increased fatigue, with 36% showing a decreased capacity to concentrate on work. We saw changes in eating patterns, with 14.5% of adolescents reporting loss of appetite. These youngsters presented physical symptoms, and 27.4% of them showed some degree of somatisation. We ought to note that 4.3% (five adolescents) answered the question “I would like to kill myself” in the affirmative. The age group showing the highest average depression score was the 17-year-old group (11.8). When we compare the average scores by age group and sex, we saw that regardless of age female adolescents had higher average scores than the males. For total scores of the BDI-II above 13 (the presence of some degree of depressive symptoms) there was a clear predominance of the female sex (82% versus 18%).

Although the questionnaires were anonymous, following their administration the students were informed of the existence in the school of an office for the support of the adolescent’s health (GASA). Thus, the adolescents were told that they had the option of seeking help from this office whenever they needed it. Out of the adolescents that resorted to the GASA, five were referred to the adolescent services in our hospital because they showed signs of depression.

DISCUSSION

A large number of studies have tried to analyse the presence of depressive symptoms in adolescents10. In many instances, the studies have noted the difficulty in making a differential diagnosis between psychiatric pathologies and the conflicts characteristic of adolescence. Depressive symptoms are frequently found in adolescents, contributing significantly to absenteeism and school failure, and are an important factor in the engagement in high-risk behaviours10,11. The presence of depressive symptoms does not necessarily entail a psychiatric diagnosis. Feelings of depression may be normal responses to adverse events, only to be considered pathological if they last too long or are disproportionate to the triggering event11,12.

We have seen an increase in the cases of depression among adolescences, which is probably due to a decreased capacity of parents to cope with stress, and to a low frustration tolerance13,14.

The total scores obtained are slightly lower than those seen in other studies, but the percentage of students with severe depressive symptoms is the same as those found in other series (5%)10,13-15.

As described in the literature, the female sex shows a higher incidence of depressive symptoms than their male counterparts1,10,15. This, according to some authors (Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus, 1994), is due to a greater number of risk factors in the female sex as compared to the male sex, a fact that is more manifest during adolescence17. Taking this into account, it would be good if it were possible to identify those adolescents who are at risk of developing depressive symptoms early on, not only for the healthcare professional, but also for teachers, classmates, and parents, who are in the first line of contact with the youth. The earliest symptoms may be subtle, so it is important to be watchful at all times.

In the academic year of 1998-99 the GASA was established in one of the secondary schools of the city centre of Viseu (Portugal). This office consists of a team of professionals from the Tondela-Viseu Hospital Centre in Portugal (a child psychiatrist, a paediatrician, several residents of paediatrics and clinical psychology, and a nutritionist). The purpose of this group is to offer support to the adolescents in any situation directly or indirectly related to their health. Leaving the hospital and reaching out to these youth offers a unique opportunity for health professionals to work in the field and help adolescents get the help that they need in their own environment. The possibility of detecting indicators of depressive symptoms early on allows for preventive interventions and for the development of peer support programmes for these youth. The presence of depressive symptoms in this age group is correlated to low self-esteem levels and a higher propensity to engage in illegal and high-risk behaviours, such as alcohol and drug use. Considering this, it is of utmost importance that we identify at-risk adolescents. To minimise the risk of depression, it is important that the adolescent has a social support network, such as the family, peers, and the school.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors report that this article was awarded as one of the best ten posters presented at the 61 Congreso Nacional de la AEP (National Congress of the Spanish Association of Paediatrics), held in Granada on May 31st and June 1st and 2nd 2012.

ACRONYMS: BDI: Beck Depression Inventory • GASA: Gabinete de Apoyo a la Salud del Adolescente (Office for the Support of the Adolescent’s Health).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Cook MN, Peterson J, Sheldon C. Adolescent depression: an update and guide to clinical decision making. Psychiatry. 2009;6(9):17-31.

- Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE, Laraque D. GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): I. identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299-e1312.

- Lobin L. Depression in adolescents: epidemiology, clinical manifestations and diagnosis [on line] [consulted on 10/02/2012]. Available at www.uptodate.com version 19.

- Gorenstein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventary and the state-trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian Subjects. Braz J Med Biological Res. 1996:453-7.

- Allen JP. An overview of Beck’s Cognitive Theory of Depression in Contemporary Literature [on line] [consulted on 12/08/2012]. Available at www.personalityresearch.org/papers/allen.html

- Ambrosini PJ, Metz C, Bianchi MD, Rabinovich H, Undie A. Concurrent validity and psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory in outpatient adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:51-7.

- Gorestein C, Andrade L. Inventário de depressão de Beck: propriedades psicométricas da versão em português. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 1998;25(5):245-50.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparotion of Beck Depression Inventaries-IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. J Personality Assessment. 1996;3:588-97.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, Tx: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

- Oliveira-Brochado F, Oliveira-Brochado A. Estudo da presença de sintomatologia depressiva na adolescência. Rev Port Saúde Pública. 2008;26(2):27-36.

- Bahls SC. Aspectos clínicos da depressão em crianças e adolescentes. J Pediatria. 2002;78(5):359-66.

- Avanci JQ, Assis SG, Oliveira R. Sintomas depressivos na adolescência: estudo sobre fatores psicossociais em amostra de escolares de um município do rio de janeiro. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24(10):2334-46.

- Cordeiro R, Claudino J, Arriaga M. Depressão e suporte social em adolescentes e jovens adultos. Rev Iberoamericana Educación. 2006;39:1-9.

- Cardoso P, Rodrigues C, Vilar A. Prevalência de sintomas depressivos em adolescentes portugueses. Análise psicológica. 2004;4(XXII):667-75.

- Fleming JE, Offord DR. Epidemiology of childhood depressive disorders: a critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990; 29:571.

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:809.

- Nolen-Hoeksame S, Girsus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bull. 1994;3:424-43.

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:56.

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:760.

- Moreland CS, Bonin L. Psycopharmacological treatment for adolescent depression [on line] [consulted on 10/02/2012]. Available at www.uptodate.com version 19.3

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaaufman J, Dahl RE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past ten years. Part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(11):1427-39.

- Fonseca MHG, Ferreira RA, Fonseca SG. Prevalência de sintomas depressivos em escolares. Pediatria. 2005;27(4):223-32.

Comments

This article has no comments yet.