Vol. 24 - Num. 93

Original Papers

Usefulness of telemedicine in paediatric emergency care during the COVID-19 pandemic

Adrián García Rona, Eva Arias Vivasa, Carmen Martínez del Ríob, Rosa M.ª González Tobosoc, Deborah Forrester Zapatad, Patricia Fernández Garcíab, Marta Bote Gascóna

aUnidad de Neuropediatría. Instituto del Niño y del Adolescente. Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid. España.

bServicio de Pediatría. Instituto del Niño y del Adolescente. Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid. España.

cPediatra. CS Ciudad de los Periodistas. Madrid. España.

dPediatra. CS Guzmán el Bueno. Instituto del Niño y del Adolescente. Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid. España.

Correspondence: A García. E-mail: drgarciaron@gmail.com

Reference of this article: García Ron A, Arias Vivas E, Martínez del Río C, González Toboso RM, Forrester Zapata D, Fernández García P, et al. Usefulness of telemedicine in paediatric emergency care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2022;24:23-9.

Published in Internet: 25-01-2022 - Visits: 4551

Abstract

Introduction: our healthcare system has undergone an unprecedented reorganization, prioritizing the care of patients with COVID-19 symptoms. Telemedicine has emerged as a useful alternative in the post-COVID era. The aim of the study was to assess the usefulness of the Twitter® messaging service as a telemedicine tool for the screening of urgent pathology.

Material and methods: cross-sectional, retrospective and descriptive study of a telemedicine programme developed by a team of specialists in paediatrics and its subspecialities during the state of alarm. We collected demographic data and the number and reasons for consultations based on the presenting signs and symptoms and how they were conveyed (text, photo and/or video). We analysed the number of resolved concerns, referrals and the degree of user satisfaction.

Results: the service managed a total of 182 consultations, mostly made by women (71%) and during the first weeks of the survey (70%). All consultations included text, accompanied in almost 1/3 of the cases by audiovisual content (27.2% photo, 4.6% video). The average age of the managed patients was 2.72 ± 2.74 years and the main reasons for consultation were fever, exanthema and respiratory difficulty. Of all consultations, 18.13% were related to COVID-19, and only 8.24% led to referral.

Conclusions: although telemedicine cannot replace face-to-face assessment and there are still technical and legal limitations, our results suggest that it could be a promising alternative to improve access, reduce triage times, coordinate available resources, and decrease the risk of contagion and the saturation of health care facilities.

Keywords

● COVID-19 ● e-health ● PandemicINTRODUCTION

Since the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) a pandemic in March 2020, its global spread and evolution has tested the capacity of health care systems in dozens of countries.

To avoid collapse and address the exponential increase in cases, the Spanish health care system has undergone an unprecedented reorganization, giving priority to patients with symptoms of COVID-19 and limiting non-urgent hospital-based care to minimise the risk of infection. In the specific case of paediatric patients, the Autonomous Community of Madrid centralised paediatric care in 2 hospitals. As a direct consequence of this redistribution, there has been a drastic reduction in the availability of medical care, which has confronted health care workers with novel ethical concerns.

In this context, health care workers, institutions and scientific societies have taken a step forward in the communication with the community, increasing their presence in social networks (SNs) substantially and generalising the use of information and communication technologies to overcome barriers to care delivery during this public health crisis.

Digital health (e-Health) is a broad concept that includes telehealth services, telemedicine (direct care of patients for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment), telediagnosis and tele-education.

The use of telemedicine to provide care to paediatric patients has emerged as a useful alternative in the post-COVID ear. Teleconsultation allows quick, specific and safe access to health care to children whose access to medical care has been restricted, thus reducing the risk of acquiring or transmitting infectious diseases.1-5 Although there are concerns regarding privacy and confidentiality, there is mounting evidence of the effectiveness of medical intervention based on video or audio consultation for a broad range of paediatric emergencies.2

Both patients and their families have understood the need to conduct a large part of their medical consultations remotely (through text messages, videoconferencing or telephone calls). However, save for a few recommendations, a standardised protocol for communication with patients during the pandemic has not been established, and each facility or professional has carried out this activity based on whatever resources were available.

The Twitter messaging service is quick, reliable and allows direct communication through a variety of devices without the need of an immediate response and with the possibility of exchanging messages, attaching files, making an audio call or a video call with acceptable quality and security levels.

The aim of the study was to describe the utility of the Twitter messaging platform for remote paediatric triage to avoid unnecessary visits to hospitals and resolve minor health problems in children that do not require in-person medical care during the period in which Spain was under the state of alarm and the reorganization of urgent care in the Community of Madrid.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective and descriptive study on the usefulness of the Twitter messaging platform as a telemedicine tool for screening of urgent pathology in paediatrics during the months that Spain was under the state of alarm in response to the health care crisis caused by COVID-19.

Development of the telemedicine programme

We recruited a team of paediatricians and residents in paediatrics and paediatric specialities in a tertiary care hospital and 2 primary care centres in the Community of Madrid.

All members of the team were trained by simulation to familiarise them with the use of social media and with virtual interactions with potential patients. The training programme covered various legal aspects concerning the management, confidentiality and privacy of the patient, with an emphasis on the need to respond exclusively to private messages. This type of interaction requires that potential patients/legal guardians request contact with the provider and authorise the submission of information, which, from a legal standpoint, could be understood as express consent by the party, by voluntarily submitting data to obtain professional advice. In addition, this medium allows submission of multimedia files (photographs and videos) that can improve decision-making.

We developed a shift roster to cover consultations in the shortest possible time over 24-hour periods and a WhatsApp group that included every member of the team to allow interconsultation if questions emerged concerning a specific subspeciality.

Each day was divided into 3 shifts, each covered by one medical resident that sorted the received queries and a specialist that supervised every managed case.

Publicizing of the telemedicine programme

We created a Twitter account under the name Equipo Pediatría HCSC (HCSC Paediatrics team, @EquipoHCSC), and created a profile to inform Twitter users of the purpose of the account and the terms of use prior to their voluntary and spontaneous access to the telemedicine service. The Bio stated the main purpose of the account: “We address your concerns through direct messages to avoid unnecessary visits to the emergency department while the state of alarm due to COVID-19 remains active” and pinned an explanatory tweet so patients would know that consultations should be made through private (direct) messages.

After setting up the account, we launched an audiovisual publicity campaign in social media, defining the topic with different hashtags: “#COVID19”, “#QuedateEnCasa” (stay home), “#confinamiento” (lockdown), “#telemedicina” (telemedicine) “#SomosClinico” (we are the Clinico), “#YoMeQuedoEnCasa” (I stay home) etc., and mentioning the main scientific societies (@aepediatria, @aepap, @SEPEAP, @lasecip…).

Telemedicine programme

In each consultation, the first step was remote triage by means of standardised questions based on the paediatric assessment triangle: general appearance and health, work of breathing and skin colour.

Depending on the presenting concern and the triage:

- If the concern was clinical and was not deemed to require urgent care, the concern was addressed and information given on warning signs that had to be watched for, making it clear that, should those warning signs arise, a new consultation should be made or the patient should be brought to the emergency department for in-person assessment.

- If the concern was clinical and was deemed to require urgent care, the patient was referred to the hospitals available in the corresponding autonomous community.

- If the reason for consultation was not strictly clinical (questions concerning infant/child care or public health measures related to the pandemic), information was provided along with reliable sources (websites of scientific societies, professional blogs, etc) where information on the subject of consultation could be obtained.

Assessment of the telemedicine programme

We retrieved all the messages sent to the @EquipoHCSC account from March 14, 2020 to the resumption of paediatric care services. We collected demographic data on the patient and the family member that initiated the contact, the date and reason for consultation, and the number of times that users requested this service.

In the analysis, we classified data based on the signs and symptoms. We also took into account whether they were accompanied by a media file (photo or video), and, if the consultation was related to COVID-19. We analysed the number of resolved concerns and the number that required referral to the emergency department for in-person assessment.

Lastly, we assessed the level of satisfaction with the care received by means of a satisfaction survey in which satisfaction was rated from 0 (least possible satisfaction) and 10 (maximum possible satisfaction) sent a few days after the consultation.

RESULTS

During the state of alarm, the @EquipoHCSC profile received more than 7000 visits and established a network of contacts (‘following”) with the main scientific associations in paediatrics and related individual profiles with the most “followers”, and got a total of 443 followers by the end of the lockdown period.

The team managed a total of 182 consultations initiated by 138 individuals. Up to 35 families made more than 1 consultation for different reasons and at different times during the study period.

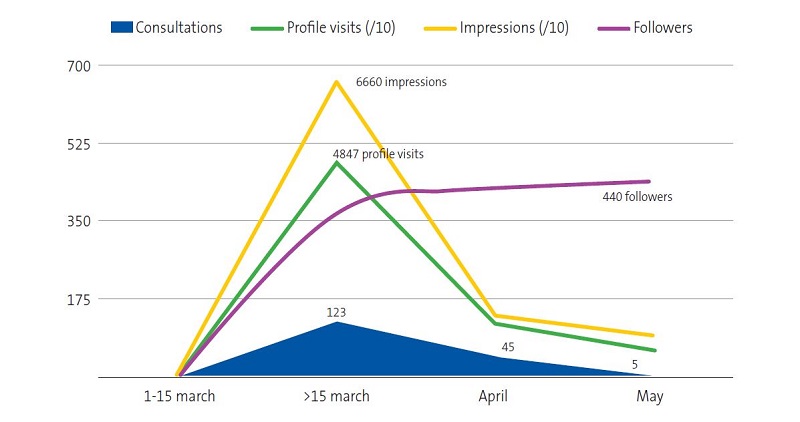

Seventy-one percent of the users were female, and, in most cases, they were the mother of the patient. Seventy percent of consultations were submitted in the first 15 days after the profile was created. Forty-nine percent were submitted in the first week and 18.8% in the second, and the number declined progressively as the situation improved. Figure 1 presents the characteristics and evolution of the Twitter profile during the confinement period.

From a clinical standpoint, the team managed 138 patients aged 2 days to 11 years, with a mean age of 2.72 ± 2.74 years (interquartile range: 3.58 years). Of this total, 31.8% supplemented the description of the clinical manifestations with audiovisual media (27.2% pictures, 4.6% videos).

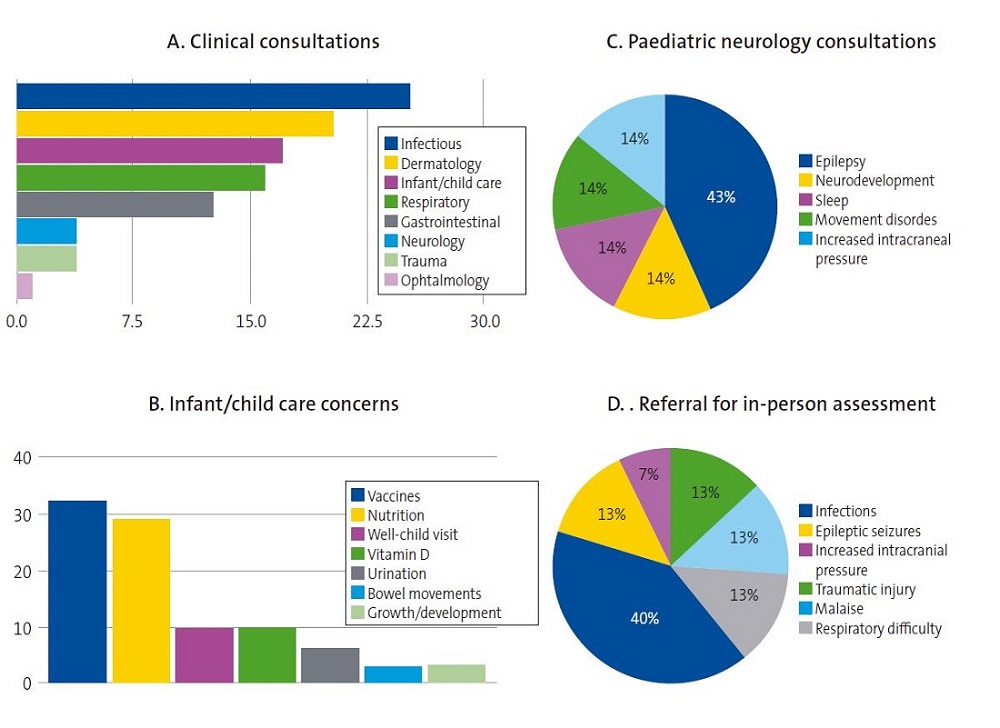

Based on the reason for consultation and the initial triage, 82.8% of the consultations made were purely clinical and the remaining 17.2% had to do with concerns regarding infant or child care.

When we analysed the messages by clinical group, we found that the main presenting concerns had to do with infectious diseases (25.3%), cutaneous problems (20.3%), infant or child care (17.0%), respiratory conditions (15.9%), gastrointestinal conditions (12.6%), neurologic conditions (3.8%), trauma (3.8%) and ophthalmological conditions (1,0%).

The most frequent reason for consultation was fever, followed by exanthema of sudden onset and respiratory difficulty. These three symptoms also amounted to the majority of the presenting concerns that involved an infectious, cutaneous or respiratory condition.

The clinical groups in which we found the most variety in the consultations were general paediatrics and paediatric neurology. Only 18.1% of consultations had to do with COVID-19.

Of all the managed patients, only 8.2% had to be referred for in-person evaluation.

Figure 2 presents the clinical characteristics of the messages received in the profile.

| Figure 2. Clinical characteristics of the consultations and most frequent reasons for in-person assessment |

|---|

|

All the consultations were managed and resolved through multimedia messaging (text, pictures or video), and the number of messages required in each conversation varied widely depending on the reason for consultation, the initial description of the case and the level of anxiety of the family. The mean response time was 9.9 minutes.

When it came to the level of satisfaction, 87.6% of users actively expressed satisfaction with the initiative and the care received, and the service received a mean rating of 7.8 ± 1.7 points over 10.

DISCUSSION

Spain has a national health system (NHS) that offers a set of public health services that guarantee universal access to emergency care to all inhabitants.

In the NHS, users can freely and voluntarily access urgent care services both at the primary care level and in hospitals, guaranteeing equity. However, this can promote frequent misuse of these services, saturating them with consultations for banal concerns.6,7

In the case of urgent paediatric care, parents frequently choose to visit emergency departments, either for work-related reasons, the flexible schedule or simply convenience. It is estimated that a large portion of these visits could be avoided.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, our healthcare system has undergone an unprecedented reorganization, giving priority to patients with symptoms of COVID-19 and limiting non-urgent hospital-based care to minimise the additional risk of infection.5

In this context, telemedicine has become a first-line tool to overcome current barriers in urgent care, relieve the pressure on the health care system, facilitate access of patients to health professionals and reduce the transmission of the virus due to unnecessary hospital visits.8

The published outcomes show that telemedicine is useful for diagnosis of common acute paediatric diseases in terms of the reproducibility of diagnosis compared to in-person visits, the degree of satisfaction of the patient and the potential reduction in health care costs.3,4,9 In our study, we used Twitter because it is a widely used SN that offers a messaging service that would allow direct interaction with other users quickly and privately with acceptable levels of quality and security.

Interactions with the Twitter profile happened quickly. In the first 15 days of the state of alarm, there was an exponential increase in the number of followers and the bulk of the total consultations took place. This favourable response was probably due to timing, as it coincided with the period of highest uncertainty and fear of the epidemiological context and with the restructuring of paediatric urgent care in the Community of Madrid.

Similar to what has been described in the literature, infectious diseases were the most frequent reason for consultation, followed by skin problems and infant/child care concerns.10 We ought to highlight that nearly one third of the patients (31.8%) spontaneously submitted image or video files to complete the clinical information.

Although based on the outcomes and the level of satisfaction (87.6% of users actively expressed their satisfaction) we consider that clinical decision-making was correct, the percentage of patients referred to emergency departments for in-person assessment was much lower compared to the scientific literature (20-30% compared to 8% in our study).9 Our results may be due to the short period of time and the epidemiological context in which the study was conducted.

Although we believe that our findings support the usefulness of telemedicine for triage of paediatric patients, the results must be interpreted with caution for different reasons and limitations. First, the study was conducted during the worst period of the pandemic, which could have promoted the acceptance of a telemedicine programme delivered through a SN. In addition, we were unable to compare the severity of diseases managed in telemedicine consultations compared to in-person visits. This could be a source of bias, as disease severity may affect the decision whether to use telemedicine or not. Patients with mild symptoms might consider consultation unnecessary, while patients with severe or unstable disease could resort directly to hospital services. Lastly, although our legal framework does not have specific or sufficiently detailed regulations, we cannot neglect to consider the ethical or legal concerns associated with our study, or the challenges to data protection of the system that we used.11-13

Notwithstanding, we consider that telemedicine was a reasonable alternative in the exceptional situation that we were living. In addition, the use of a private messaging system could be understood as consent from the involved party that is therefore granted by the user making the consultation.

Still, given that telemedicine will account for more than half of the consultations in upcoming months, we should consider the challenges posed by this tool from a technical and an ethical standpoint, both for the patients (security, privacy and confidentiality), and for the medical professionals providing the care.

Our findings suggest that telemedicine may be a promising alternative to improve access to health care, reduce triage times, coordinate available healthcare resources and even follow up patients at home, avoiding unnecessary travel, decreasing the risk of disease transmission and the saturation of health care facilities.8,14

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in relation to the preparation and publication of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS

NHS: National Health System · SN: social network.

REFERENCES

- Burke BL Jr, Hall RW. Telemedicine: Pediatric Applications. Pediatrics. 2015;136:293-308.

- Mehrotra A. The convenience revolution for treatment of low-acuity conditions. JAMA. 2013;310:35-6.

- McConnochie KM, Conners GP, Brayer AF, Goepp J, Herendeen NE, Wood NE, et al. Differences in diagnosis and treatment using telemedicine versus in-person evaluation of acute illness. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:187-95.

- Ray KN, Shi Z, Gidengil CA, Poon SJ, Uscher-Pines l, Mehrotra A. Antibiotic Prescribing During Pediatric Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine Visits. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20182491

- Bloem BR, Dorsey ER, Okun MS. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Crisis as Catalyst for Telemedicine for Chronic Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:927-8.

- Hostetler MA, Mace S, Brown K, Finkler J, Hernández D, Krug SE, et al. Emergency department overcrowding and children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:507-15.

- García de Ribera MC, Bachiller Luque MR, Vázquez Fernández M, Barrio Alonso MP, Hernández Velázquez P, Hernández Vázquez AM. Triaje de urgencias pediátricas en Atención Primaria española mediante teléfono móvil. Análisis de un modelo en un área de salud. Rev Calid Asist. 2013;28:174-80.

- Santos-Peyret A, Durón RM, Sebastián-Díaz MA, Crail-Meléndez D, Gómez-Ventura S, Briceño-González E, et al. E-health tools to overcome the gap in epilepsy care before, during and after COVID-19 pandemics. Rev Neurol. 2020;70:323‐8.

- Harvey JB, Yeager BE, Cramer C, Wheeler D, McSwain SD. The Impact of Telemedicine on Pediatric Critical Care Triage. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:555-60.

- Crane JD, Benjamin JT. Pediatric residents’ telephone triage experience: do parents really follow telephone advice? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:71-4.

- Recomendaciones del ICOMEM sobre Telemedicina ante la crisis sanitaria. In: Ilustre Colegio Oficial de Médicos de Madrid [online] [accessed 20/01/2022]. Available at https://fundadeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/icomem-telemedicina.pdf

- Muñoz Fernández l, Díaz García E, Gallego Riestra S. Las responsabilidades derivadas del uso de las tecnologías de la información y comunicación en el ejercicio de las profesiones sanitarias. An Ped (Barc). 2020;92:307.

- Bravo Acuña J, Merino Moína M. Uso de nuevas tecnologías en la comunicación con los pacientes, su utilidad y sus riesgos. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020;92:251-2.

- Vidal-Alaball J, Acosta-Roja R, Pastor N, Sánchez U, Morrison D, Narejos S, et al. Telemedicine in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aten Primaria. 2020;52:418-22.

Comments

This article has no comments yet.